The new wave of the pandemic that has hit India interfered with the interim assessment of Narendra Modi’s second tenure as Prime Minister in a positive light. Although the mortality rate from coronavirus in India is lower than in other countries, there is hardly any family there that has not lost friends or relations during the epidemic. The peak of the second wave is likely to have passed already, but the best-case scenario, according to experts, will see the situation improve no earlier than late in May.

India’s authorities were not ready for a storm of such magnitude. Not only medicines are in short supply—the most acute problems have to do with the lack of medical oxygen. The need for oxygen has increased sharply and manifold.

There is no doubt that excessive carelessness and confidence that the worst is over played a very cruel joke with the Indian leadership and the expert community. However, amid conditions when the country lived in a normal mode and considering that another nationwide lockdown was not announced, it was impossible to control mass family gatherings, and upholding the ban on Kumbh Mela would entail a negative reaction from exalted orthodoxies, while the cancellation or postponement of elections in several important states would inevitably be perceived by N. Modi’s critics in India and abroad as an encroachment on democracy.

Today, parliaments in half of all states in India are not controlled by the ruling BJP. At the same time, for the purposes of advancing the ambitious reforms that are consistently carried out by N. Modi’s government, strong positions in the states are of great importance, since many issues that determine the effectiveness of the implementation of the reforms initiated by the national government fall within the jurisdiction of regional authorities.

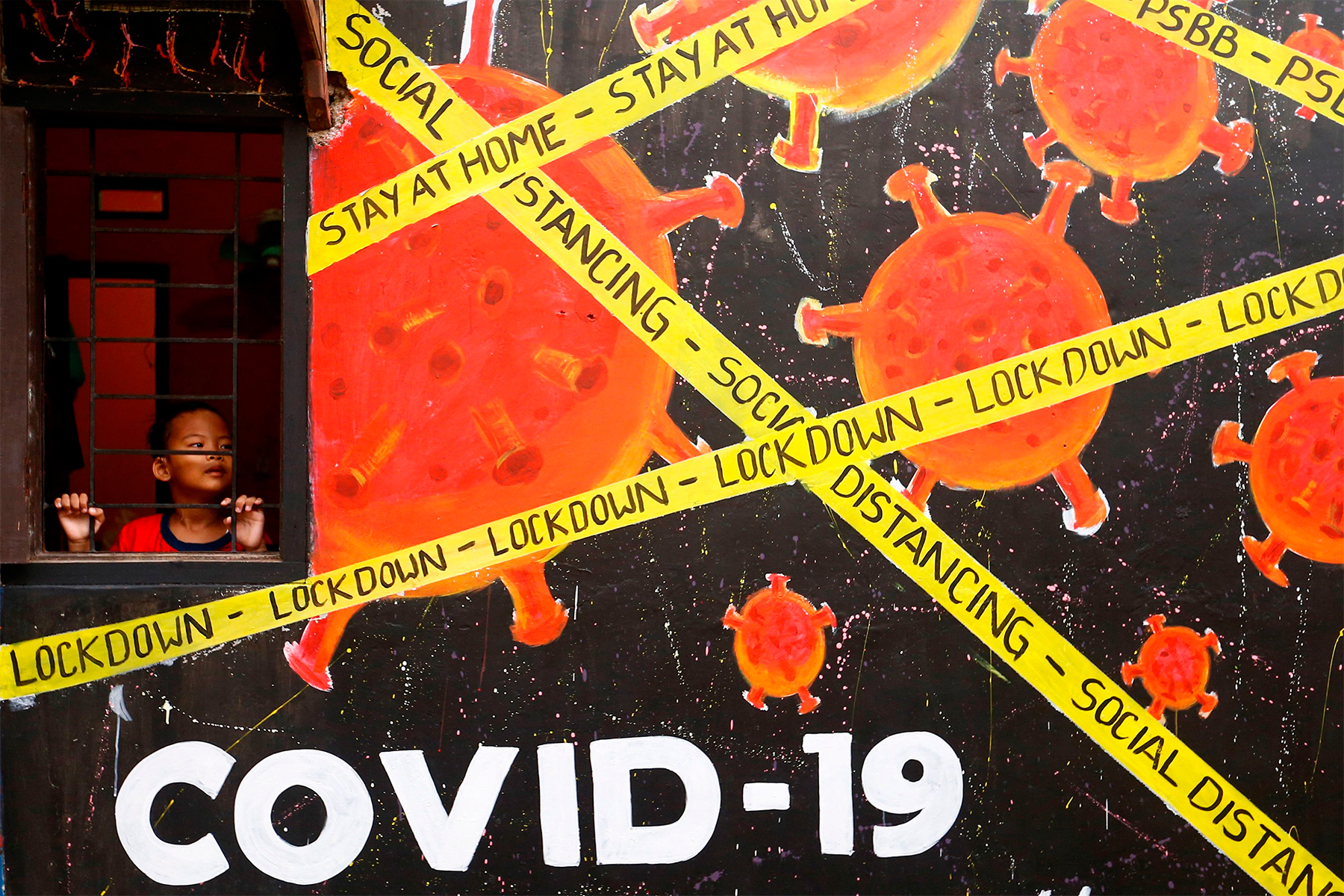

May 2021 marks two years since Narendra Modi was re-elected as the prime minister of India. In total, the Indian leader has been in power at the national level for 7 years, since 2014. The new wave of the pandemic that has hit India interfered with the interim assessment of Narendra Modi’s second tenure as Prime Minister in a positive light. In a very short span of time, the number of COVID-19 infected persons in India has skyrocketed—from 8,000 detected and officially reported cases as of February 1, 2021 to 12,000 as of March 1. This figure exceeded the enormous 400,000 infections per day in early May. At the moment, this indicator is in decrease. There are particularly many cases among young and middle-aged people. Doctors speak about a new strain of virus in India that proliferates easily and is more infectious and dangerous for young people. A nationwide lockdown was not announced, but local authorities impose restrictions of their own. Life stands still again in India’s capital, New Delhi. According to official statistics, the total number of COVID-19 cases in India, throughout the entire time of the pandemic, exceeds 20 million, with more than 220,000 people dead.

Weathering the storm of the pandemic

Although the mortality rate from coronavirus in India is lower than in other countries, there is hardly any family there that has not lost friends or relations during the epidemic. The peak of the second wave is likely to have passed already, but the best-case scenario, according to experts, will see the situation improve no earlier than late in May.

India’s authorities were not ready for a storm of such magnitude. Not only medicines are in short supply—the most acute problems have to do with the lack of medical oxygen. The need for oxygen has increased sharply and manifold. Despite industrial production being urgently re-profiled, constructing new facilities and purchasing special equipment abroad, as well as logistics and transportation issues, remain the main factors that impede any effective solution to the problems with providing patients with the required oxygen.

When a nationwide lockdown was introduced in India a year ago, it became one of the most stringent and longest in the world, which brought its results—a large-scale catastrophe was averted. This success seemed to be a miracle and was attributed to various factors, including hot Indian climate, mass vaccination of children against other infections or cross-immunity.

In India, many people were under the impression they had previously encountered a similar infection or, perhaps, fell ill and recovered asymptomatically; therefore, herd immunity might already have been achieved in India. In the summer of 2020, the country began to gradually return to work, as economic growth forecasts were adjusted towards more optimistic estimates.

India developed its own coronavirus vaccine, Covaxin, while the production of AstraZeneca’s vaccine has been launched, both for India’s needs and for export. In April 2021, Indian regulators also approved the Russian Sputnik V vaccine. First Sputnik V shipments were received from Russia, and local production will begin soon. Several more vaccines are currently under approval procedures by the Indian authorities. As one of the world leaders in producing vaccines and drugs, India not only exported coronavirus-related medicines on a commercial basis but also provided them free of charge to many countries, primarily to its neighbors, as a gesture of friendship and humanitarian support. In total, India has supplied about 80 million doses of vaccines to 85 countries around the world.

India’s own vaccination campaign, which started off in early 2021, has been too slow, even though it is progressing at a record pace if compared to other countries. As of May 11, 2021, in a country of 1.39 billion people, only 37 million were fully vaccinated, while the total number of injections stood at 170 million. At the same time, in order to achieve mass immunity, India has to vaccinate at least 600 million people with both components of the vaccine.

The first ones to be vaccinated were frontline workers, including doctors, police officers, teachers and military personnel. Then older people and adults over 45 years old were vaccinated, and only recently it was announced that all citizens over 18 years old are eligible for a jab. Since March, vaccine exports have been suspended, as there are currently not enough vaccines for India’s own needs. With the rush spurred by the second wave of the pandemic, demand currently exceeds the nation’s production capacity.

Things are getting back to normal—but at what cost?

After combatting the epidemic successfully in 2020, Indians were full of enthusiasm and self-confidence, so a new coronavirus storm caused a deep shock in the country. In addition to the slow vaccination drive, many events in April and March contributed to the rapid proliferation of the infection. While the whole country was forced to sit at home during these spring months last year, and not working, India was already living its usual life in 2021, with the usual peak of social activity looming in February, March and April. Before the onset of the very hot summer months, life across the country is in full swing.

It was during these months this year that spring festivals such as Holi, mass pilgrimages and the famous Kumbh Mela as well as sports matches in huge stadiums and pre-election rallies with the participation of tens of thousands of people were simultaneously held all over India. Today, India’s Prime Minister is criticized not only for the fact that he was too quick to announce victory over the pandemic in India but also failed to take sufficient measures to limit social contacts in the country until vaccination became widespread. Critics of Narendra Modi and of his advisers believe that stringent national restrictions should have been re-introduced once the number of infections began to rise early in March.

There is no doubt that excessive carelessness and confidence that the worst is over played a very cruel joke with the Indian leadership and the expert community. However, amid conditions when the country lived in a normal mode and considering that another nationwide lockdown was not announced, it was impossible to control mass family gatherings, and upholding the ban on Kumbh Mela would entail a negative reaction from exalted orthodoxies, while the cancellation or postponement of elections in several important states would inevitably be perceived by N. Modi’s critics in India and abroad as an encroachment on democracy.

Sealing the fate of reforms

Since 2019, a total of nine state parliamentary elections have been held in India. Of these, the ruling at the national level Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) under the leadership of N. Modi was able to win only three – in Arunachal Pradesh, Haryana and Bihar. In five electoral campaigns that took place in India this April, the only success for the BJP was that the party managed to maintain its leadership in Assam. Meanwhile, in Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry, the BJP failed to achieve significant results, with the parliamentary assemblies of these states still controlled by regional parties. Large-scale efforts by Narendra Modi personally and by his teammates were directed towards wining leadership in West Bengal, one of the most important states for India (with the capital in Kolkata). However, the popularity of the Indian Prime Minister, who spent a lot of time in March this year in West Bengal addressing thousands of people at election rallies was not enough to challenge Mamata Banerjee, India’s only female chief minister, leader of All India Trinamool Congress, West Bengal’s most popular party, and an irreconcilable critic of Narendra Modi. M. Banerjee won the elections in West Bengal for the third time in a row. Voting lasted a record time and was held in eight rounds – in March and partially in April. M. Banerjee’s party won 216 out of 294 seats in the legislative assembly of West Bengal. The BJP secured 75 seats. Although this is significantly more than the 3 seats won by the party in 2016, this result did not meet BJP’s expectations; it was a big disappointment and did not reflect the efforts that the party and its leader spent on campaigning in this state.

Today, parliaments in half of all states in India are not controlled by the BJP. Critics of N. Modi, who significantly increased in numbers following the disastrous second wave of the pandemic, see the results of these regional elections as confirmation that India remains committed to pluralism and democratic traditions, despite the BJP’s willingness to strengthen the “top-down governance” in the country. In fact, India only retains the traditional situation, where voters prefer a leader like N. Modi at the national level, while keeping their preferences for regional political forces, well familiar to them, at the state level.

At the same time, for the purposes of advancing the ambitious reforms that are consistently carried out by N. Modi’s government, strong positions in the states are of great importance, since many issues that determine the effectiveness of the implementation of the reforms initiated by the national government fall within the jurisdiction of regional authorities—for example, in healthcare, infrastructure, agriculture, land relations, taxation, and others. Despite the weakened approval ratings of the prime minister, the next national elections will be held in India in 2024, and N. Modi has enough time to restore the level of support and push the planned reforms forward.