India’s Pandemic Predicament: Gnarled Odyssey of Politics but Performance too

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 4, rating: 4) |

(4 votes) |

Assistant Professor of International Relations and Strategic Studies, at the Department of International Relations, Goa University

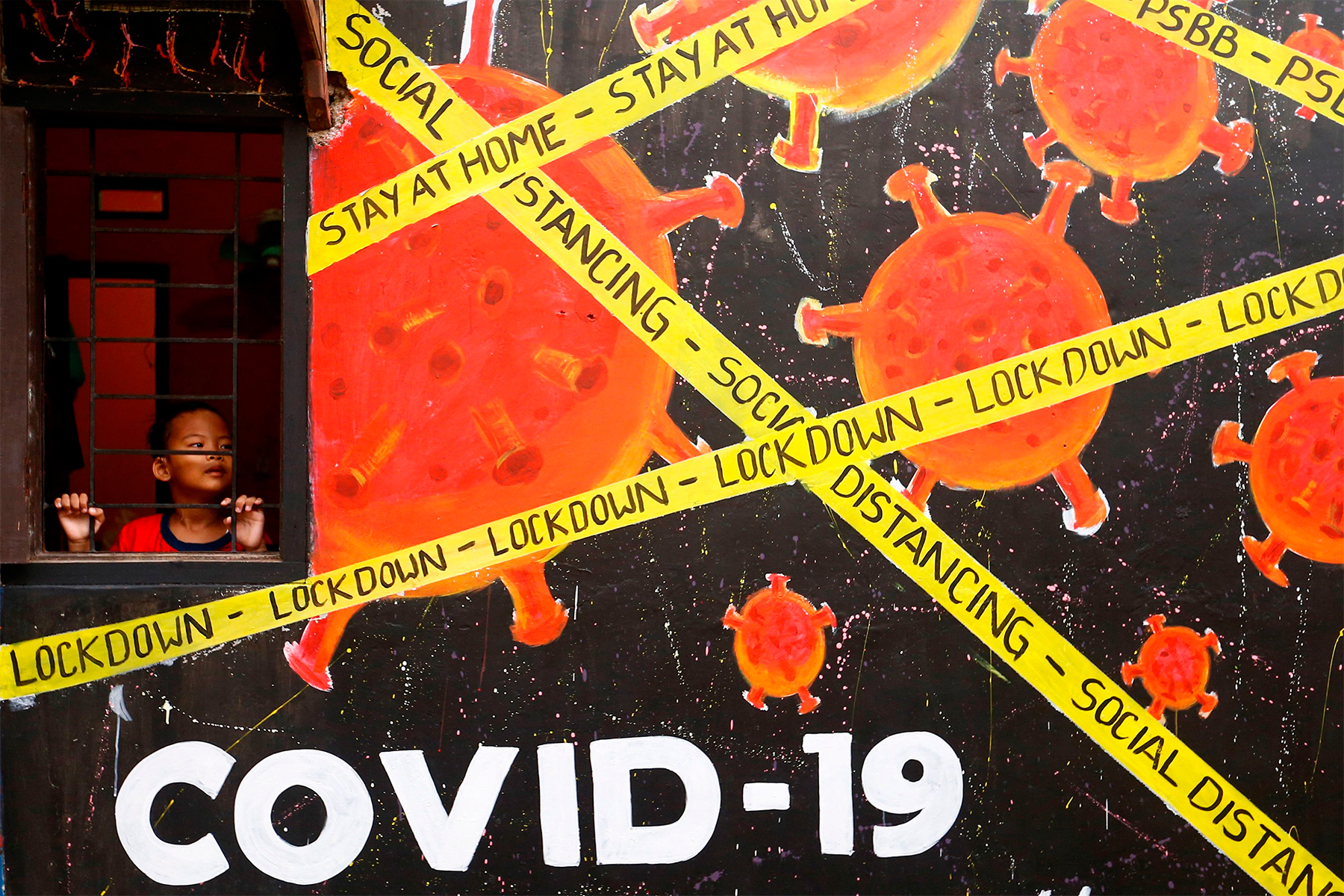

During the first wave of the pandemic, India appeared to have accomplished more than its most illustrious peers in the opulent North and across the Global South when it staved off the first wave of the pandemic, with modest damage to life and livelihoods, through most of 2020.

What has contributed to this fall from grace, as the world’s most populous democracy finds itself in the cynosure of global attention of concern and pillory on account of the ravaging second wave of a severely mutating pandemic threatening to embarrassingly overwhelm the nation’s abysmal healthcare apparatus?

It is time to enliven spirits with interspersing news that holds keys to subduing the pandemic, a second time. India is the only country to soon be able to boast half a dozen vaccines and more, and multiple indigenous ones, which augurs well for its humungous vaccination drive going forward.

In much the same way as the world marvels at how India counts its federal electoral returns within a day, they would be amazed by the pace of inoculations by the time we are done and dusted. Just recently, India’s DRDO in collaboration with Reddy’s Laboratories has launched an orally administrable anti-COVID drug that is billed as a potential game-changer.

The manner in which the world has responded so effusively and of its own volition to ameliorate India’s anguish is a testament to how the Indian pandemic diplomacy has stood on a pedestal, navigating through strategic competition, ideological prejudice and nationalist hegemony by prioritizing human beneficence. The daily case numbers are beginning to plateau and decline, albeit in the sobering knowledge that they are dismounting from a four-fold threshold higher than that during the apogee of the first wave. This would involve enduring the hard paces. And all this, as informed speculations over a third wave, this time directly impacting the kids, in the same vein as this second wave has disproportionately impinged on the youth, stares us in the face, demanding greater sagacity, smoother coordination within government and between governments and a more robust preparedness from the ruling elites and the political class across the entire spectrum of persuasions.

It’s a once-in-a-century pandemic. Yet, its lacerating proliferation has sufficed to break the backs of national healthcare systems globally. The pandemic has constituted a moment of unprecedented reckoning for professional credence and rectitude of policymakers and practitioners across frontiers, while existentially assailing every fundamental precept and tenet that underpins the liberal global order. Arguably, in pursuance of efficient transcendental cooperation, it has exposed the superficial and fragile notion of the pluralised sovereign collectivisation.

One in three around the world is either an Indian or a Chinese. The pandemic has exposed these two populous demographics to a number of vagaries and vicissitudes. Beijing has been widely perceived as successful in smothering the home-grown pathogen through shuttering and surveillance measures, construed as draconian by many but mightily effective too. As a result, economic and societal rebound is underway and gathering momentum. India, by contrast, has had to proceed the innately democratic way, which exudes the challenging features of societal indiscipline, chaos and dissonance, and involves the travails of forging consensual functioning within the obvious fetters of multi-party democratic federalism. Despite this high bar, in relative terms India appeared to have accomplished more than its most illustrious peers in the opulent North and across the Global South when it staved off the first wave of the pandemic, with modest damage to life and livelihoods, through most of 2020.

So what has contributed to this fall from grace, as the world’s most populous democracy finds itself in the cynosure of global attention of concern and pillory on account of the ravaging second wave of a severely mutating pandemic threatening to embarrassingly overwhelm the nation’s abysmal healthcare apparatus?

Taming the First Wave: The Modi Government’s Alacrity on Display

Global Victory Over COVID-19: What Price Are We Willing to Pay?

When the virus proliferated during early 2020, India was invariably perceived as the weak link, with no easy choices on hand. No wonder then that Prime Minister Modi bit the bullet and opted for a stringent national lockdown, albeit abruptly declared—something only a courageous statesman like him could muster the gumption to do, while being fully sentient of the dislocating impact it would exert on livelihoods in a country where small and medium sector enterprises are the lifeline to the predominantly informally employed workforce and where many of its people are still poor and reliant on state emanating hand-outs. However, it was the necessary evil to ensure primal survival at a time when the pandemic was taking hold in urban centres, with the impending potential to infiltrate and swaddle deep stretches of mofussil towns and the vast countryside, a spectre which—if realised—would bring to bear doomsday scenarios that were part of Western media commentaries.

The first ingress of the strain was an outcome of mobility, as was evident in the dint of India’s industrial centres and globally connected urban hubs across the West and the South of the nation, gripped by the Wuhan virus. Despite the withering criticism of how the government had cataclysmically stalled the economy and society, which led to a hyperbolic tout of the biggest episode of intra-nation human migration in conventional understandings of peacetime. Such a sudden measure, which certainly could be improved upon in hindsight, helped to subdue the virus and its ominous morbidity. The Indian government was seen to be proactive and earnest through the early months of the lockdown, fire-fighting on multiple fronts—from the Prime Minister assuming leadership in reaching out to provincial dispensations led by political outfits of varied ideological stripes and keeping them on the same page; the Home Minister, in coordination with states, ably helming a 24x7 War Room to mitigate, to the extent possible, the egregious effects of essential supplies and logistics shortages nationwide; whilst the Ministers of External Affairs, Health and Civil Aviation collectively stewarded the process of outbound and inbound evacuations of foreign nationals and Indians stranded abroad, under meticulously conducted diagnostic testing and surveillance methods. And all this as India confronted, unlike any other, an unprovoked stealthy and savage Chinese military putsch in the Himalayan reaches.

The economy plausibly tanked, enduring the sharpest of contractions across advanced and emerging nations alike. However, in a country where over 90% of the workforce is engaged in informal employment, the equation squaring lives and livelihoods is a devil and the deep blue sea proposition, tempered in the hard prudence that, if lives are spared, then livelihoods can be recouped, but not vice versa. The government did inject an unprecedented fiscal stimulus that stood at close to 20% of GDP, compartmentalised into curated economic sectors handholding. Besides, the government sought to shore-up rudimentary subsistence, through public welfare support measures, aimed at ensuring food security and minimal income to the impoverished.

While liberal Western nations were seen engaging in a self-serving cannibalised scramble for virus counteracting equipment and logistics from one another, not only did India ramp up imports from all possible avenues but also tasked entrepreneurs at home to supplement inventories of medical gear. The country actually cared for its South Asian neighbours as well, in including their citizens within India’s own exertions to bring forlorn nationals back, offering technical expertise and assistance, and frontloading commonly pooled financial assistance through the SAARC mechanism. All this, when long-standing iconic experiments at integration, such as the European Union, failed to address the urgent existential requirements of its members, leading to a public admission and apology from no less than the European Commission President of having failed its members at a juncture of the existential reckoning.

The result of the foregoing was that India which saw its first few hundred cases in March 2020, just prior to the lockdown, through executing months of compulsive detachment of human mobility and socialisation, ensured that the daily caseload surge did not exceed one hundred thousand, widely surmised as a significantly depressed nationwide statistic in the context of India’s population. And even then, the federal government was not letting its guard down, procuring substantial numbers of ventilators from the PM Cares Fund and innovatively re-purposing the berths in its rail-coaches into emergency hospital beds, should the need arise. No wonder that while public resentment and rancour could have been comprehensible (and was evident across leaderships around the world), there was little ire against Modi as his approval ratings remained steady, both empirically and anecdotally, a vindication that his regime—despite the constraints—was seen as exhausting every sinew to tide over the unforeseen public health exigency and prioritising precious lives at all costs. The fact that the first wave subsided, with just about one hundred and fifty thousand fatalities, just under ten million overall cases, and with the positivity threshold not scaling the double-digit mark, it was a remarkable stave-off by any stretch of imagination, befuddling opinionated sections, at home and abroad.

The Falter and Flounder of the Second Wave 2021: Flat-Footed and Gloating Modi Regime

What then explains India’s current flounder with the second wave of the pandemic, and where precisely did it falter? Simply put, the country sleep-walked itself into the crystal ball gaze of delusional grandeur and gloating comfort, failing to maintain its guard of high vigilance and sobriety about the pandemic and its virulent manifestations.

It’s true that what’s struck India is not any ordinary tidal-wave that has been sweeping around the globe, but a tsunami of monstrous proportions borne out by the current double mutant variant of the original virus and its steep trajectory of ascent up the charts of daily caseload and fatalities. Notwithstanding the limited numbers of air-bubbles that India kept operating with foreign nations through the turn of 2020, which always kept the potential for further globally ruminating strains, such as the UK, Brazilian and South African variants, to make their way into India, this has also shown up the fact that this largely airborne pathogen strain has transmissibility legs of its own, transcending sovereign frontiers.

Hence, it belies reasoning that India should have lowered its guard so soon after taming the first wave and deluded itself into believing that further waves would not be upon it, when they were scarring geographies around the globe, with a messaging to this effect coming from no less than Prime Minister Modi when he was seen to churlishly boast at the time of India’s vaccine roll-out that the country was effectively on path to vanquish the virus. Such fallacious notions, signalled from the top, got mistakenly internalised in the disposition of provincial administrations, keen to return to securing livelihoods and economic recoup. They went back to grossly relaxing the effective enforcement of COVID protocols for testing and surveillance, as society in general relapsed back into reckless demeanours rooted in flagrant disregard of social distancing.

While the federal government would like us to believe that they were persisting with high levels of vigilance, the hard facts inform otherwise. Why was no tangible action taken to buttress oxygen requirements when limitations on this score in the event of a second wave hitting us were flagged from various forums, be it the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health late last year or even by the Prime Minister’s Task Force of medical experts? Why was such a response left to the hapless states when it is public knowledge that they are in no position to bolster capacities in this regard? And if it was indeed the state’s remit to accomplish this, then, what message does the nationally ruling BJP send when close to half of the states within the Union are governed by it? Why could the Prime Minister—who did to his credit conduct multiple interactions with Chief Ministers to ensure coordination during the first wave of the pandemic—not convene even one such online meeting with CMs to forewarn them of this potentially impending oxygen crisis during the early part of 2021 but has rather chosen to hide in the refuge of some innocuous communications having been sent to the States?

Financial Bubbles in the Coronavirus Era

If this wasn’t bad enough, what compounded matters was how the ruling BJP lead the charge of returning to expedient politicking, with the Prime Minister, the Home Minister and most ministers within Cabinet blissfully preoccupied with campaigning in provincial round of elections amid the case surge in Maharashtra and Karnataka. Even if one were to concede that PM Modi had a handle on things, given his sterling ability to work long hours and blend party work and governmental duties, it still made for callous optics. Irony was rich in a specific instance when in a recent address to the nation the Prime Minister was preaching strict conformity with COVID protocols when earlier that day none of that was on offer or observance at his multiple electioneering rallies.

No wonder that the states that went to the hustings are progressively reporting rising incidence of COVID cases, which are expected to peak much later than those early bird states, in an eclectic country, where the concept of a nationally discernible peak in cases is quite an understandable misnomer.

It must objectively be said that the magnitude of India’s raging second wave would have overwhelmed any healthcare system across the world, particularly on evidence of how much more acclaimed ecosystems have literally been on their knees worldwide. India’s skeletal healthcare apparatus is a worst kept secret with a nationally indexed bed to patient ratio of 1:2,000 that accentuates further when scrutinized in the Hindi heartland states, such as Bihar, where the patient to doctor ratio stands at a disbelieving 1:44,000 and more.

But this spectre has not been the function of the seven years of PM Modi’s ascent to power—it is the despicable upshot of seven decades of apathetic and malignant neglect, of what should routinely be a building block foundation of modern-day country and society. To Mr. Modi’s credit, his seven years in power have thus far initiated a salutary change in this realm, if only a small morph within the larger picture, where the domain of ‘Health’, in terms of its growth, management and superintendence, is constitutionally enjoined as a subject of competence for the ‘State’ (provinces within India).

Since 2014, the federal government sanctioned the centrally funded establishment of no less than fourteen All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) facilities across different states, eleven of which have duly been commissioned and are now operational. Besides, it is PM Modi’s empathetic concern for the less privileged that has seen his government enshrine arguably the world’s largest healthcare insurance regime for the poorest and underprivileged sections of the Indian society, to the tune of Rs. 500,000 of medical treatment expenses annually across state and private hospitals alike. Empirical evidence is replete with anecdotal reports of scores of individuals being the benefactors of this path-breaking scheme, which has been extended so as to cover COVID-19 treatment too.

These measures would at least facilitate combatting the scourge of a virus. Besides, we had the Prime Minister avail this unfortunate transpiring to brandish the imperative for dedicated epidemiological and virology infrastructure within hospitals and across states, making this an integral element of his ‘AtmaNirbharata’ (National Self-Reliance) strategy.

From the time the first wave had been parried, provincial Chief Ministers, particularly those from within the opposition ranks, were seen clamouring for greater autonomy to tend to this crisis, resisting the proclivities of the Prime Minister to over-centralise matters as part of his seemingly authoritarian propensities and an impulse to arrogate all credit but scapegoat stakeholders for blame. While there is merit in these behavioural styles of PM Modi, no doubt, the States were pursuing greater agency and ownership in the crisis, as if they were gilt-edged exponents at taming such catastrophe-verging situations. Mahatma Gandhi famously averred that India lives in its villages. As an extrapolation to that, it can be argued that the economy story of India is quintessentially a measure of states administering themselves as models of good governance and, notwithstanding their perpetually cash-strapped orgies, ramping up and leveraging the inherent capacities and operational capabilities.

Yet, outside of certain creditable examples which can be characterised as aberrational outliers, both in normal conditions and even during this pandemic (Kerala during the 2020 wave; Uttar Pradesh during the current 2021 wave etc.), the wherewithal of states and their administrative machinery are, for the most part, woefully inadequate.

Hence, it comes as no surprise that hospitals within states are fund-lacking, even when it comes to the rudimentary necessity of in-house oxygen plants, although their presence would still have been insufficient. Since the metastasising oxygen crisis has been upon India, the federal government has turbo-charged into action, ordering the commissioning of close to six hundred huge oxygen plants across the country through the auspices of the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO) and the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI), both federal agencies, besides deploying all three services within the armed forces to bridge the gaps and engineer expeditious mobility of oxygen supplies across the country. However, this basically means playing onerous catch-up with a dynamic virus spreading like wild-fire.

As a matter of fact, politicking even in times of such monumental crises is not unique to democracies. Since the onset of the pandemic, one has witnessed crass politicks playing itself out in the U.S. where the Trump White House constantly feuded with Democratic Party Governors; down South in Brazil where President Bolsonaro has been in running battles with the leftist ideology disposed consortium of provincial chieftains over requiting logistics from China; and even in Australia, where Prime Minister Morrison has locked horns with Labour Premiers in States. In India, however, the mutual blame game between the federal government and state authorities has been deeply agonizing. In fact, the Courts have had to intervene and order, including in a matter where the plea for redressal was brought by the BJP government in Karnataka against its own party’s federal government, alleging erroneous submissions by the Modi government about oxygen quantum delivered.

The ‘Vaccine Maitri’ Initiative: Two Clever by Half or Reaffirming Indian Exceptionalism?

There is no gainsaying that the global entities, united in a salutary manner, managed to eruditely stumble upon a vaccine in a flat 327 days, an unprecedented occurrence in itself. However, at the cost of sounding cynical, it may be said that while wide-ranging cooperation was proactively forthcoming when it came to discovering a vaccine, questions need to be asked whether such collegial actions have persisted since, as regards ensuring relatively equitable vaccine access to humanity in its grapple against this universal threat?

Needless to say, the unqualified answer is a resounding no. Amidst the richer countries paying lip service to the notion of vaccine equity (such that the WHO-mandated COVAX alliance has been floundering in its bid to proffer accessibility to impoverished societies at affordable prices), India has gone out on a limb and stayed true to its internalised belief that “no one is safe until everyone is safe”, anchored in its innately espoused philosophical moorings of Vasudaiva Kutumbakam, ‘the entire Universe is One Family’, implying that we are all in this together.

Hence, as the US and China showed themselves up as exponents of vaccine nationalism and hegemony alike, India, since the early going, has leveraged the fact of cogent pharmacological research, innovation and production facilities, leading to its early roll-out of the vaccine, partaking its production with the immediate small neighbours and low-income and least developed nations across the broad swathe of the Global South.

But it would be a mistaken notion to harbour that such munificence by New Delhi simply fulfils its hallowed good neighbourly duty under the self-avowed ‘Neighbourhood First’ strategy. Instead, it could be perceived as an effective ploy at substantive soft-power projection vis-à-vis China, whose travails surrounding vaccine efficacy were out in the open or, for that matter, as a bounden obligation to the COVAX initiative that India had enthusiastically signed on to and that had come at the expense of Indian lives and well-being.

The numbers speak for themselves with over six million vials heading outbound to some six dozen countries, yet constituting only about 30% of the total inoculation consummated at home till date. At a time when the most fiscally and logistically privileged and majorly urbanised countries with significantly smaller demographics have struggled to vaccinate portions of their populaces, India, since rolling out its vaccinations on 16th January 2021, has eclipsed 180 million jabs in arms, with close to a quarter of such shots leading to full vaccination of its citizenry.

If anything, during the disbursal of vaccines abroad—in many cases mandated on the drug co-development conditionality, such as the Serum Institute of India’s (SIIs) co-venture with Oxford University and AstraZeneca—the domestic pace of vaccinations was far from impacted, as it only kept steadily gathering steam through the months of January to April 2021.

Russia Moves East, India West, Straining Ties

Critics and detractors have fronted legitimate questions, as to whether the Modi government should have exercised greater sagacity in adequately planning for spiking contingencies at home rather than get carried away by its own reputation of being the “pharmacy of the world” preceding itself on this front. But then, it’s this generosity and exceptionality of genuine concern for humanity, manifested by India, not just on vaccines lately but harking all the way back to hydroxychloroquine and medical logistics supplies that is now seeing India receive effusive logistical assistance from all parts of the globe, cutting across ideological juxtapositions and political persuasions—not out of any kind of patronizing empathy by those seemingly better-off at present, instead, out of a sense of camaraderie for and solidarity with a friend and partner in distress.

The incumbent gross shortfall in vaccine doses, which has materially slowed the incidence of vaccination from an average of about 2.5 to 3 million a day, possibly allowing India to attain the herd-immunity threshold deep into 2022, to well under a million since the middle of April. This is expected to endure for at least a couple of months, and certainly some elements of disjointed coordination between the government and vaccine suppliers, as mismanagement and crappy politics between the federal and provincial dispensations, have to ascribe the blame.

While India has been remarkable, outside of the SII-Oxford AstraZeneca COVISHIELD vaccine, in rolling out its own indigenous vaccine COVAXIN developed collaboratively by Bharat Biotech and the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR) and reckoned by none less than the U.S. Centre for Disease Control and Dr. Anthony Fauci as clinically effective in subduing the double mutant B.1.617 virus strain, its negotiations for sourcing internationally developed vaccines has been a cumbersome process. Notwithstanding India’s early embrace of the Russian Sputnik V in a co-production arrangement with Reddy’s Laboratories, it has only just seen the light of day, geared for going commercial and wider dissemination across India from next month. Negotiations with Pfizer have been running rings over the drug company’s insistence on obtaining prior ‘indemnification’ from potential lawsuits arising out of the abuse of the drug. Besides, there are storage issues and wider conveyance. India’s oldest private vaccine developer ‘Biological E’, the pioneer of the Tetanus and Hepatitis-B vaccines, is in advanced stages of co-development with its peer partner, the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, of what is prospectively anticipated to be 300 million doses of the most affordable of jabs.

This potential breakthrough could be intriguing, adding grist to the mill of what has been the inaugural Quad Leaders’ Summit takeaway of collaborative harness of India’s production capacities, in pursuance of a billion affordable doses, for lower-income ASEAN and South-Pacific island nations.

Besides, multiple independent corporate entities have come forward, evincing interest to undertake the production of Bharat Biotech’s COVAXIN doses, these being subject to requirements of intellectual property transfer and bio-safety conditions. Companies find themselves in uncharted territory in terms of being saddled with unprecedented demand and are actively foraging for decentralised production facilities across States within the Indian Union, with principal candidates being Maharashtra and Gujarat.

The vaccine gap has also been in the spotlight on account of the Prime Minister’s virtually left-field move to announce an expansion in vaccine eligibility for those in the age group of 18-44 in a markedly young country where 65% of population boasts a mean age of 35 years and under and where only a seventh of the population has received some vaccination, with only 3% fully inoculated.

With estimations of exponential inventories of vaccine doses to close to two billion expected to steadily file through August through December 2021, it is expected that India which has thus far been a pace-setter alongside the U.S. in inoculating 180 million of its citizens, will regain momentum and accomplish a critical mass in vaccinations across its poorest communities and village landscapes by 2022.

Drawing Conclusions

Amidst the enveloping penumbra of gloom and doom and the tendency for Indians to deprecate and disparage themselves—much more than those abroad—it’s time to enliven spirits with interspersing news that holds keys to subduing the pandemic, a second time. India is the only country to soon be able to boast half a dozen vaccines and more, and multiple indigenous ones, which augurs well for its humungous vaccination drive going forward.

In much the same way as the world marvels at how India counts its federal electoral returns within a day, they would be amazed by the pace of inoculations by the time we are done and dusted. Just recently, India’s DRDO in collaboration with Reddy’s Laboratories has launched an orally administrable anti-COVID drug that is billed as a potential game-changer.

The manner in which the world has responded so effusively and of its own volition to ameliorate India’s anguish is a testament to how the Indian pandemic diplomacy has stood on a pedestal, navigating through strategic competition, ideological prejudice and nationalist hegemony by prioritizing human beneficence. The daily case numbers are beginning to plateau and decline, albeit in the sobering knowledge that they are dismounting from a four-fold threshold higher than that during the apogee of the first wave. This would involve enduring the hard paces. And all this, as informed speculations over a third wave, this time directly impacting the kids, in the same vein as this second wave has disproportionately impinged on the youth, stares us in the face, demanding greater sagacity, smoother coordination within government and between governments and a more robust preparedness from the ruling elites and the political class across the entire spectrum of persuasions. Besides, if Mr. Modi—in whom the Indian people repose unparalleled faith, for his irreproachable assiduousness, integrity, and national commitment—can reign in his image-building and cult persona impulses, all shall be well in time.

(votes: 4, rating: 4) |

(4 votes) |

The First Take on Humanity’s KPI in Combating the Coronavirus

Financial Bubbles in the Coronavirus EraThe global economy has fallen into the trap of a "new abnormality," where incessantly creating money does not solve pressing socioeconomic problems

Russia Moves East, India West, Straining TiesRussia and India are going to lose a lot if they have to take sides in this forthcoming US-China rivalry