There is cautious optimism about the current negotiations between the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Syrian government. Under the March 10, 2025 agreement, which was backed by US mediation and under intense pressure from Turkey, an operational framework has been established to bring the two sides closer and expedite the process of integrating the military and civilian structures established by the Kurdish self-administration in northeastern Syria (Rojava) into the state institutions and administrations. The Damascus-Rojava negotiation track has recently seen remarkable momentum.

However, there are still many challenges in this process. Even while the parties say they agree to the amalgamation, the details—especially the implementation procedures—are problematic. Localized conflicts have broken out as both sides seek to alter the balance of control and strengthen their bargaining positions.

The integration of the Kurdish self-administration and its military branch, the Syrian Democratic Forces, or SDF, into the new Syrian state and its army has yet to yield definitive results. Given that certain participants on both sides favor confrontation and decisive action to negotiation, there are still several barriers that could impede this process and force it away from the negotiating table and into the battlefield. However, international and regional power dynamics and calculations continue to play a major role in the situation in northeastern Syria (Rojava). Negotiations between Damascus and Rojava will therefore take longer than specified in the March 10th

agreement since local parties have far less leeway. At least for the near future, there may be more small-scale skirmishes in particular locations in the future, but they will not turn into a full-fledged conflict.

There is cautious optimism about the current negotiations between the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Syrian government. Under the March 10, 2025 agreement, which was backed by US mediation and under intense pressure from Turkey, an operational framework has been established to bring the two sides closer and expedite the process of integrating the military and civilian structures established by the Kurdish self-administration in northeastern Syria (Rojava) into the state institutions and administrations. The Damascus-Rojava negotiation track has recently seen remarkable momentum.

However, there are still many challenges in this process. Even while the parties say they agree to the amalgamation, the details—especially the implementation procedures—are problematic. Localized conflicts have broken out as both sides seek to alter the balance of control and strengthen their bargaining positions.

Setting Up the Damascus-Rojava Negotiations

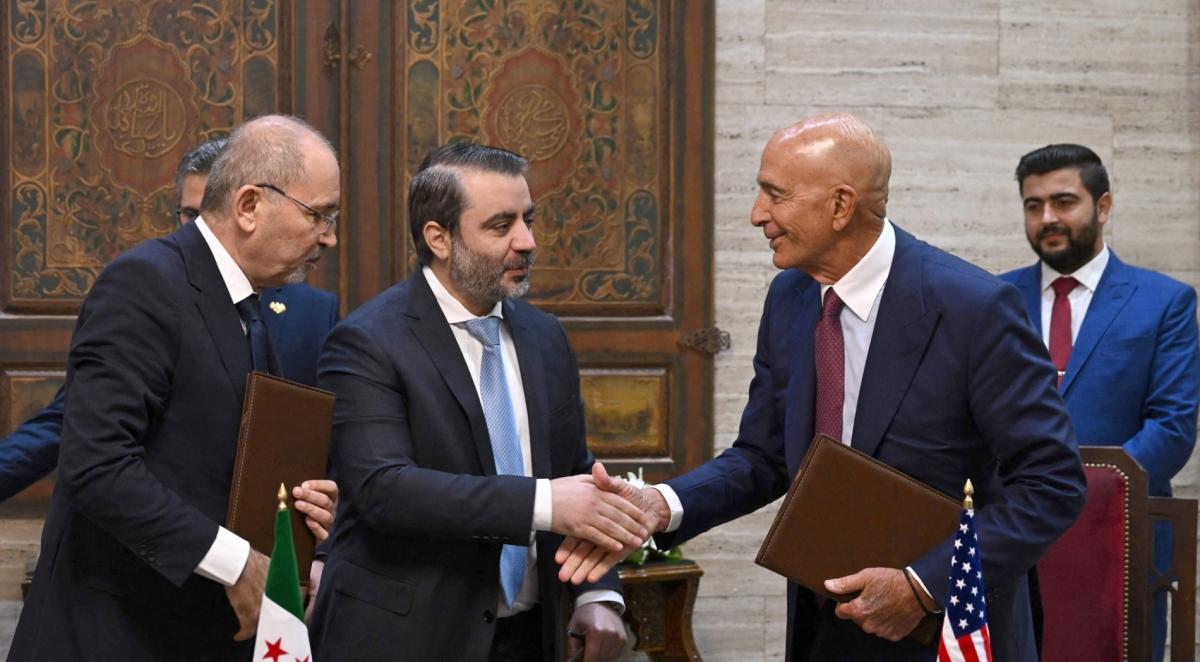

The administration of US President Donald Trump is applying pressure to accelerate negotiations between the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Syrian government. Brad Cooper, the head of US Central Command, just visited Syria on October 6 in response to confrontations between SDF and Syrian government forces in Aleppo, demonstrating this pressure. Cooper's meeting with President Ahmed al-Sharaa and Mazloum Abdi resulted in a plan to carry out the March 10 agreement. Building on the changes brought about by the ceasefire deal in Gaza, these US initiatives are a part of a larger plan to restructure the strategic context of the region.

The talks also follow Turkey's increasing pressure on the SDF, which escalated tensions and threatened a military operation if the SDF did not implement the March 10 agreement between Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa and SDF commander Mazloum Abdi, which was signed in Damascus and had an implementation deadline of the end of this year. The SDF's persistent inaction, according to Turkey, might strengthen its presence and pave the way for Israeli engagement as a response to Turkey's recent actions in Syria and Gaza. As a result, Turkey approaches the SDF issue from the standpoint of its national security.

In order to break the current deadlock between the two parties and end the crisis, they appear to have followed a US policy approach, which advocates implementing the agreement gradually and partially in order to foster trust between the parties and create a state of flexibility, allowing for negotiations. The most crucial of these steps are as follows:

I. Setting up an operational framework, which is exemplified by the SDF releasing detainees from the Syrian army following the fighting in Aleppo's Ashrafieh and Sheikh Maqsoud neighborhoods, hosting a military gathering in Tabqa to ease tensions, and allowing officials from both sides to visit each other to exchange management techniques and operational procedures.

II. In order to maintain Syria's unity and sovereignty, the technical and administrative committees start debating the specifics of the amalgamation. These discussions would be led by two main pillars: Damascus agrees to a certain amount of local governance and self-security in exchange for self-administration in Rojava, relinquishing its demand for decentralization. Washington appears to understand that this would require striking a balance between the two sides.

III. The SDF opposes the transfer of Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa to the Syrian government for military reasons, as doing so would eliminate the water barrier that currently forms a line of contact between the two sides and would give the Syrian government a military advantage. This is because there are fewer Kurds in the entire Deir ez-Zor governorate, as well as in the cities of Raqqa and Tabqa. Additionally, it will free the Arab tribes in the two areas from SDF control and serve as a human resource for the government during the conflict.

The SDF refers to a verbal agreement under which the Damascus government would join the army as a bloc, the SDF would form three brigades operating within its areas of control, and SDF officers would be appointed to positions within the Ministry of Defense. Meanwhile, the Asayish units—the SDF’s security arm—and the Women’s Protection Units (Kurdish: Yekîneyên Parastina Jin, YPJ) would be integrated into the Ministry of Interior’s structures to ensure security in Rojava. In a clear sign of the ideological divide between the two sides, Damascus has rejected this proposal, at least for now, arguing that enlistment in the Syrian Arab Army entails significant requirements and is not an area open to experimentation.

Challenges in Merging the SDF into the New Syrian State

However, there are many difficulties in integrating the Kurdish self-government in Rojava, its military units (SDF), and its security units (Asayish and Women's Protection Unit or YPJ) into the frameworks and structures of the new Syrian state:

I. Technical challenges: Although the two sides seem to get along well at leadership-level meetings, the technical committee meetings show a great deal of complexity and an overemphasis on detail. There are now fundamental differences of perspective about the number and placement of troops, the responsibilities of division and unit commanders, and the distribution of positions, funds, and equipment. The SDF is taking advantage of these challenges and presents the government with two choices: either accept a superficial amalgamation that preserves the SDF's independent structure and areas of control while also shielding it from a Turkish military operation and reducing tensions among the Arab population in eastern Syria, or abandon the process before the year is out, giving the SDF more freedom to organize its own affairs.

II. Structural challenges: The Syrian army lacks a well-defined organizational structure, as well as regular ground troops, air force, or navy branches. What remains is an amalgamation of groups that took part in the Deterrence of Aggression" operation, each with its own leaders and members. Therefore, given the open animosity that has persisted in the relationship between some factions and the SDF troops, it will be challenging to absorb tens of thousands of SDF members and distribute them among the aforementioned factions. There are no guarantees against future conflicts with those factions, especially since some, like al-Amshat and al-Hamzat, have remained in the areas of contact with the SDF. This is true even if the Damascus government agrees to incorporate the SDF in the form of brigades and keep them operating near their current areas of control.

III. Changes in ideology: The Democratic Union Party (PYD), which leads the Kurdish self-government in Rojava, takes a secular stance and gives women a significant role in both military and political leadership. The Syrian government is adamant about not integrating the YPJ into the army, whereas the Damascus government's actions and policies are blatantly religiously conservative. There is also dispute regarding military doctrine. There should be a comprehensive national philosophy for the Syrian army, which is meant to represent all facets of Syrian society. The Kurdish self-administration and its military and security branches in Rojava, however, have a local and ethnic character that shapes their philosophy within those frameworks, creating two incompatible systems within a single structure.

IV. Political challenges: The Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) and a certain portion of the local Kurdish population aspire to independence and the creation of a future Kurdish state, which is represented by the SDF and their self-administration experiment. The weakness of the Syrian state and the existence of international and US assistance are examples of favorable circumstances. There are signs that the PKK has concentrated its efforts and efficacy in Syria and Iraq to support the independence of the Rojava region (eastern Syria) following its retreat from Turkey. Abdullah Ocalan exempted the SDF from giving up its weapons in this situation and even regarded the Rojava region as a red line. As a result, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to carry out this process without receiving equivalent concessions in terms of autonomy or extraordinary shares of positions and resources.

V. The US position: The US perspective on SDF incorporation into the Syrian army does not seem to be definitive. Washington's strategy appears to be more concerned with managing crises and delaying issues than it is with finding long-term fixes. The issue is that it is trying to maintain Syrian unity without giving up on Kurdish ambitions, which is an unsustainable approach. Kurdish troops continue to get technical and material assistance from Washington. This contradiction shows that there is internal disagreement in the US on this matter, between a group that favors control by the Syrian government control and the dismantling of militias and another that thinks the SDF's continued existence is crucial to preserving a balance in relations with Israel and Turkey.

The Stakes of Negotiation: Analyzing the SDF's Strategic Wager

A crucial component of both parties' negotiation and crisis management is betting. The SDF's wager on the time factor is particularly noteworthy in this context because it anticipates a shift in external as well as internal circumstances, such as a major conflict with a Syrian component (the Druze or the Alawites) or internal conflicts between extremists and the government, which would enable it to capitalize on these developments to maintain its independence and identity. Because the events in Suwaida heightened the Kurds' anxieties of dismantling their military organizations and giving up their weapons, the SDF utilized this as an excuse to delay the merger process.

For its part, Damascus is wagering that Turkish pressure and advancements in talks with Israel would cause the United States to change its stance, which would severely undermine the SDF's position. Additionally, it is taking advantage of the developing divisions within the SDF between the Kurds themselves—between proponents and opponents of integration—as well as with the Arabs, who make up a sizable majority in areas under Kurdish control. The power-sharing agreement that was in place prior to the overthrow of the Assad administration, which gave the Kurds control over the situation in eastern Syria, is now being demanded by this majority. The conflict between the Shammar tribe and the SDF forces is the most recent example of the significant strain in relations between Arab tribes and the Autonomous Administration in Rojava.

War is still a possibility for all sides, and the negotiations have not put an end to it. A state of alert, reinforcements on both sides, and preparations for a possible conflict are confirmed by reports. Dissatisfied with integration and reconciliation, groups and factions inside the Syrian government and Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) are attempting to fan the fires of conflict. Some SDF members think that going to war would be preferable to destroying the SDF and putting a stop to Kurdish ambitions. In addition, the SDF's better training, equipment, and discipline in comparison to a weak government force with poor coordination, leadership, and discipline would make conflict more favorable to the SDF's stance on independence. Masoud Barzani has stated that the Iraqi Kurds (Iraqi Kurdistan Region) will not watch helplessly if the Kurds in Syria are endangered, therefore the Kurds also expect substantial support from them. Furthermore, the Syrian government, fearing a coup in southern and western Syria, is probably reluctant to repeat the mistakes of the Suwaida events and will not be able to mobilize its military troops in the east of the country to combat the SDF.

On the other hand, groups supported by Turkey, which are mostly made up of tribal communities from Aleppo and eastern Syria, aim to conquer the Kurds, destroy the Syrian Democratic Forces' (SDF) infrastructure, and take control of the region's affairs. They depend on Ankara's political cover and all-encompassing Turkish military backing, which may help neutralize US forces. Turkey wants the People's Protection Units (YPG) to be completely disbanded because of their affiliation with the PKK, which it considers to be a terrorist group. However, Turkey is reluctant to launch a full-scale conflict with the SDF out of concern for the consequences for its own negotiations with the PKK.

Even if these projections might not be totally true, they serve as a motivator for the parties to go to war, which, if it happens, will spread like wildfire to all Syrian actors.

Conclusion

The integration of the Kurdish self-administration and its military branch, the Syrian Democratic Forces, or SDF, into the new Syrian state and its army has yet to yield definitive results. Given that certain participants on both sides favor confrontation and decisive action to negotiation, there are still several barriers that could impede this process and force it away from the negotiating table and into the battlefield. However, international and regional power dynamics and calculations continue to play a major role in the situation in northeastern Syria (Rojava). Negotiations between Damascus and Rojava will therefore take longer than specified in the March 10th agreement since local parties have far less leeway. At least for the near future, there may be more small-scale skirmishes in particular locations in the future, but they will not turn into a full-fledged conflict.