Over the past decades, the international system has undergone a profound transformation, driven by the rise of new powers and the gradual erosion of the Western dominated order. As Ijaz et al. (2024) argue, emerging actors increasingly challenge global governance structures, which were historically shaped to serve the interests of the Global West. This trend illustrates what Zemanek (2023) identified as a crisis of a “rules-based order” in which the sovereign will of countries is often limited by political expectations imposed from outside. While the current shifts show the ability of great powers to pursue value-based diplomacy, the position of less-influential countries and their abilities were often overlooked.

It can be said that, at the very core of value diplomacy, lies national identity as a set of core values and aspirations that define proper state behavior (Erbas, 2022). However, McKinnon (2002) noted that political action rarely comes from a set of shared values and moral truth alone, but rather from practical constraints. These limitations are even higher in times of international crisis, during which national political elites often focus on the survival of their position, rather than the state itself, and thus often end up reconsidering traditional values and alliances in favor of new ones that allow them to keep their legitimacy (Dufalla and Metodieva, 2024; Eriashev and Makarycheva 2021).

That being said, the following paper will explore the ability of small states to pursue value diplomacy in times of crisis by analyzing the political behavior of Serbia in the United Nations General Assembly since the start of the Ukrainian Crisis in 2014. It begins by outlining the core principles of Serbian foreign policy towards Russia and the values behind it, before turning to an analysis of Serbia’s UNGA voting on Ukraine-related resolutions between 2014 and 2025. Through this comparison, the study assesses whether Serbia’s actions reflect value diplomacy or the constraints of economic and geopolitical pressure and draws conclusions on the broader possibilities for small-state value diplomacy.

Serbia’s Foreign Policy: Values and Constraints

While Serbia does not yet possess a formal foreign policy strategy, its key orientations can be seen from the 2021 National Security Strategy, which emphasizes the preservation of sovereignty and territorial integrity, especially in relation to Kosovo and Metohija, pursuit of EU integration, maintenance of military neutrality, and the development of constructive relations with major global actors, including Russia, China, and the United States. That said, a useful starting point for analyzing Serbia’s foreign policy is the framework proposed by Prorokovic (2023), who argues that values, geography, and international politics are the three main pillars of any foreign policy. Using this approach will provide important insights into understanding Serbia’s behavior towards the Ukraine Crisis.

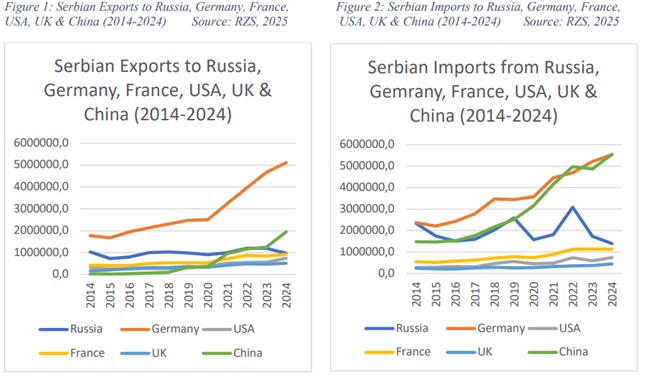

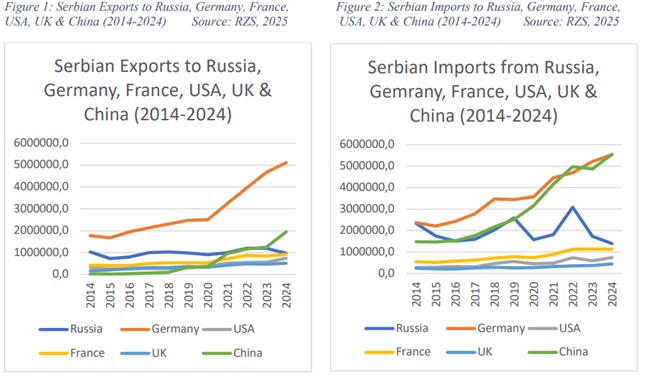

First of all, relations between Russia and Serbia rest on a deeply layered set of shared values that developed through centuries of intertwined history, the Orthodox church, Slavic cultural traditions, parallel experiences of major wars, and Russia’s consistent diplomatic support in contemporary issues such as Kosovo and Metohija (Djokic, 2020). Second, Serbia is a landlocked country surrounded by states which are mostly unfriendly to its interests, and many are members of NATO or the EU (Entina et al., 2023). Third, the Serbian economy is highly dependent on the European market, as seen in Figures 1 and 2, which makes it politically dependent on the West. Yet, regardless of the constraints, it seems that the relations between Serbia and Russia were always respectful and strong (Aghayev, 2017).

Apart from the obvious geographical distance, it seems that economic cooperation is one of the biggest drawbacks to deepening the relationship between Russia and Serbia. While these countries have a free trade agreement, economic relations remained narrowly concentrated in the energy sector, lacking significant diversification (Djokic, 2020; Islamov et al., 2024). Apart from that, Figures 1 and 2 show that since 2014, Russia has gradually lost its importance both as an export and import partner, while Germany further strengthened its dominance, and China used the Covid-19 crisis to enhance cooperation with Serbia (Entina et al, 2023). After the start of the SMO and the introduction of international sanctions against Russia, economic relations encountered new difficulties in the form of Western pressures and Moscow’s disconnection from the global financial system (Zemanek, 2023).

However, despite the geopolitical and economic difficulties that arose in 2022, it seems that the Serbian public continues to support the traditional political and cultural alignment with the Russian Federation, as it was shown in multiple surveys (NSPM 2022a, 2022b, 2023, 2024a, 2024b, 2025). In particular, more than 80% of the Serbian population continuously opposes sanctions against Russia, while around 70% blame NATO and the United States for the start of the conflict. At the same time, the public view of BRICS as a possible alternative to the EU and the main foreign partner of Serbia increased from 37.3% to 46.6% showing a deeper alignment of the population with the values of a multipolar world. One of the possible reasons for such high support is that Serbians tend to see global matters through their own lens, and the wounds from the 1999 NATO aggression on Yugoslavia are still fresh (Zemanek, 2023). Thus, the Russo-Ukrainian conflict is often viewed as an opportunity for Serbia’s traditional ally to confront the forces that once acted against Serbia. The outcomes of this crisis are perceived as decisive for the future of Serbia, its sovereignty and territorial integrity (Entina et al., 2023).

In the current multipolar context, Serbian political elites can either align with a block or try to remain formally neutral (Dokmanovic and Cveticanin, 2023). While the Serbian regime often portrays itself as a traditional partner of Russia, using the example of not introducing sanctions, the truth is somewhat different. Namely, the ruling structures in Belgrade are using the current situation mainly to extract political and economic benefits from both the East and the West, not necessarily following the values or strategic interests of the country and its people (Radeljic and Ozsahin, 2023; Zemanek, 2023).

The gap between domestic preferences, which remain strongly pro-Russian, Serbia’s structural dependence on the European market and the interests of local political elites leave the Republic of Serbia in an unfavorable position of selective neutrality. In such a context, Serbia stands at the crossroads of rising political aspirations and the structural limitations that define what small states can realistically achieve (Islamov et al., 2024; Vuckovic and Radeljic, 2024). The following section will explore how these calculations between values and constraints shape Serbia’s UNGA voting behavior.

Serbia’s UNGA Voting Record Analysis

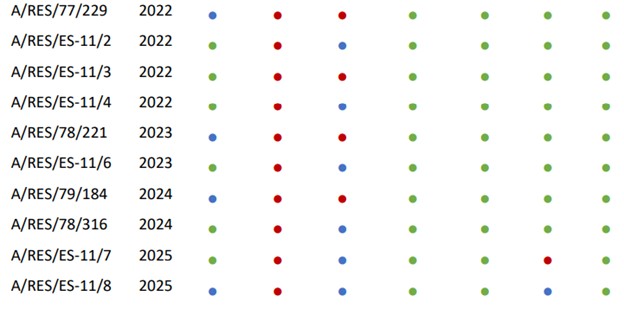

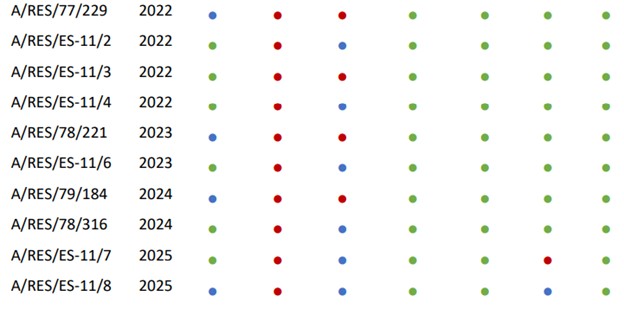

Serbia’s UNGA voting record on resolutions concerning Ukraine, as presented in Table 1, reveals a complex and evolving pattern. Considering the overall voting distribution, Serbia appears to maintain a degree of neutrality, while slightly leaning toward Russia, likely reflecting their shared values. This is evident in its votes as it voted “No” on roughly 43% of resolutions, “Yes” on 30%, “Abstained” on 22%, and “Not-voting” on 4%. However, 2022 represents a clear turning point in Serbia’s voting behavior.

Before 2022, Serbia aligned with Russia on 91% votes regarding the crisis in Ukraine, with the only difference being that Serbia did not vote on a resolution regarding Ukrainian territorial integrity due to its issues with the province of Kosovo and Metohija. However, after the start of the SMO, there is not a single vote where Russia and Serbia align. These actions show that with the intensification of Western pressures, Serbia was unable to vote based on its values and provide support to the Russian Federation.

After 2022, Serbia increasingly aligned with Germany and other major European powers, as its main economic partners, following them on approximately 58% of votes. This pattern reflects the impact of Serbia’s economic dependence and the pressures exerted by the West during this period (Entina et al., 2023; RadeljiC and Ozsahin, 2023). These votes tended to concern resolutions of the highest importance to Western countries, while Serbia strategically abstained from those of lower priority. Such abstentions were made possible by Serbia’s economic and strategic ties to China and Russia, allowing it to uphold at least some of its own foreign policy values while navigating Western pressures.

The primary reason why Serbia is mainly under semi-authoritarian economic and political influence of Germany and the EU is that the Balkans no longer lie within the interest of other major political actors who are mostly focused on Ukraine, South China Sea and the Middle East (Dokmanovic and Cveticanin 2023; Radeljic and Ozsahin, 2023). Nevertheless, value-based ties between Serbia and Russia remain strong, with Serbia being morally aligned with it, while its financial and political focus is on the strengthening new alliances with the EU (Aghayev, 2017; Belloni, 2024; Dufalla, and Metodieva, 2024). However, it appears that in times of crisis, Belgrade is unable to sit on two chairs as it seems for it to be regarded as neutral, global superpowers need to see it like that (Dokmanovic and Cveticanin, 2023).

The key factors keeping Serbian political elites balancing between the West and the East without a particular strategic vision seem to be their personal gains and the Serbian population which is strongly aligned with the Russian Federation (Islamov et al., 2024; Vuckovic and Radeljic, 2024). Based on the examined voting record, it seems that value-based diplomacy is not possible in times of international crisis, at least for small states like Serbia. To have official Belgrade more closely aligned with Russia, further expansion of cultural cooperation followed by strategic investments in the Serbian economy, is needed (Djokic, 2020).

Conclusion

To conclude, the findings of this study suggest that the practice of value diplomacy is highly dependent on the broader geopolitical constraints within which individual states operate. The Serbian case, observed through its UNGA behavior in the period between 2014 and 2022, shows that it largely aligned its positions with those of the Russian Federation, illustrating a set of historically rooted traditions and common values. However, following the start of the SMO, Western pressure on Russia and its allies escalated. This left Serbia with a reduced capacity to follow value diplomacy, due to its increasing economic dependence on Western states and its vulnerable geopolitical position as a landlocked country surrounded by regimes which are predominantly unfriendly towards Russia. Thus, this study indicates the limitations of a value-based diplomatic course when confronted with external pressures. Ultimately, the extent to which a state can uphold its values and traditions in the international arena is highly context-specific and depends on its economic sovereignty, geopolitical position, and overall capacity to withstand external pressures without causing significant harm to itself or its population.

However, it must be noted that this research is limited by its focus on UNGA voting behavior, which, despite its visibility, remains symbolic in nature, yet it remains important as it shows value preferences, geopolitical alignments and normative commitments. While there are other foreign policy indicators that suggest Serbia is still at least partially able to follow its traditional value orientation, most notably its decision not to implement sanctions against the Russian Federation, the study shows important insights into the limitations of following one’s values in the international community. That said, further research should expand the scope to other states that share values with the Russian Federation. Such studies might show additional patterns and suggest what conditions enhance the abilities of sovereign states to preserve their value-driven diplomatic behavior in times of geopolitical tensions.

Belloni, R. (2024). Serbia between East and West: Ontological security, vicarious identity and the problem of sanctions against Russia. European Security, 33(2), 284–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2023.2290048

Djokic, A. (2020). The Perspectives of Russia’s Soft Power in the Western Balkans Region. RUDN Journal of Political Science, 22(2), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.22363/2313-1438- 2020-22-2-231-244

Dokmanovic, M., and Cveticanin, N. (2023). Serbia in Light of the Global Recomposition. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, 25(4), 586–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2023.2167162

Dufalla, J., and Metodieva, A. (2024). From affect to strategy: Serbia’s diplomatic balance during the Russia-Ukraine War. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2024.2429861

Erbas, I. (2022). Constructivist approach in foreign policy and in international relations. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(3), 5087–5096.

Eriashev, N. I., and Makarycheva, A. V. (2021). Alliance-building in post-war Europe: Lessons for Russia. Russkiy Mir: International Studies, 19(4), 138–162. https://doi.org/10.31278/1810-6374-2021-19-4-138-162

Entina, E., Chimiris, E., and Lazovich, M. (2023). The prospects for Russian-Serbian relations amid sanctions (Working Paper No. 77). Russian International Affairs Council. ISBN 978-5- 6049977-8-9.

Islamov, D. R., Akhmetkarimov, B. G., Grishin, Y. Y., and Vagapova, F. G. (2024). The Russia and Turkey factors in Hungary Serbia tandem’s policies. Russia in Global Affairs, 22(1), 130–150. https://doi.org/10.31278/1810-6374-2024-22-1-130-150

Ijaz, S., Tehseen, S., Shah, F. A., Ahmed, S., & Tabani, T. (2024). Power dynamics and balance of power in international relations. Migration Letters, 21(S11), 1750–1759.

McKinnon, C. (2002). Liberalism and the Defense of Political Constructivism. New York: Palgrave

Republicki Zavod za Statistiku [RZS]. (2025). Data.stat.gov.rs [Data set]. URL: https://data.stat.gov.rs/?caller=SDDB&languageCode=en-US