Strategic Implications of the Melting Arctic Sea Ice for Indonesia

(votes: 11, rating: 4.82) |

(11 votes) |

HSE University Student

The following research assesses the strategic implications of the melting Arctic sea ice for Indonesia, an archipelagic nation, whose interest is driven by existential vulnerability and geoeconomics necessity. There is imperative to address the impacts of climate change, provided the magnitude of changes occurring, particularly in climate and sea level rise. Arctic melt contributes to a serious sea level rise in Indonesia, projecting the inundation of approximately 118,000 hectares of territory by 2050. Furthermore, the loss of sea ice intensifies the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle, creating greater climate uncertainty that severely threatens national food security.

In addition, there are various geopolitical challenges that stem from the opening of the Northern Sea Route (NSR), which directly threatens to reduce trade volume in the Malacca Strait and diminishes Indonesia’s diplomatic leverage under the Global Maritime Fulcrum (GMF) framework. In response, Indonesia is pursuing a Blue Ocean Strategy. This includes formalizing efforts for Permanent Observer Status in the Arctic Council to access critical climate data, establishing clean energy partnerships with Nordic states, and developing a Maritime Industry Niche. Using qualitative sources, such as open official state documents, statements, media, and academic research by both Indonesian and international authors specializing in the Arctic region and its implications, research points to the cruciality in the strategic investment in specialized Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul (MRO) facilities for high-value ice-class vessels, integrated with clean fuel bunkering, to transform the NSR threat into a strategic economic opportunity and maintain Indonesia's regional influence.

The Arctic and Indonesia's Non-Territorial Stake

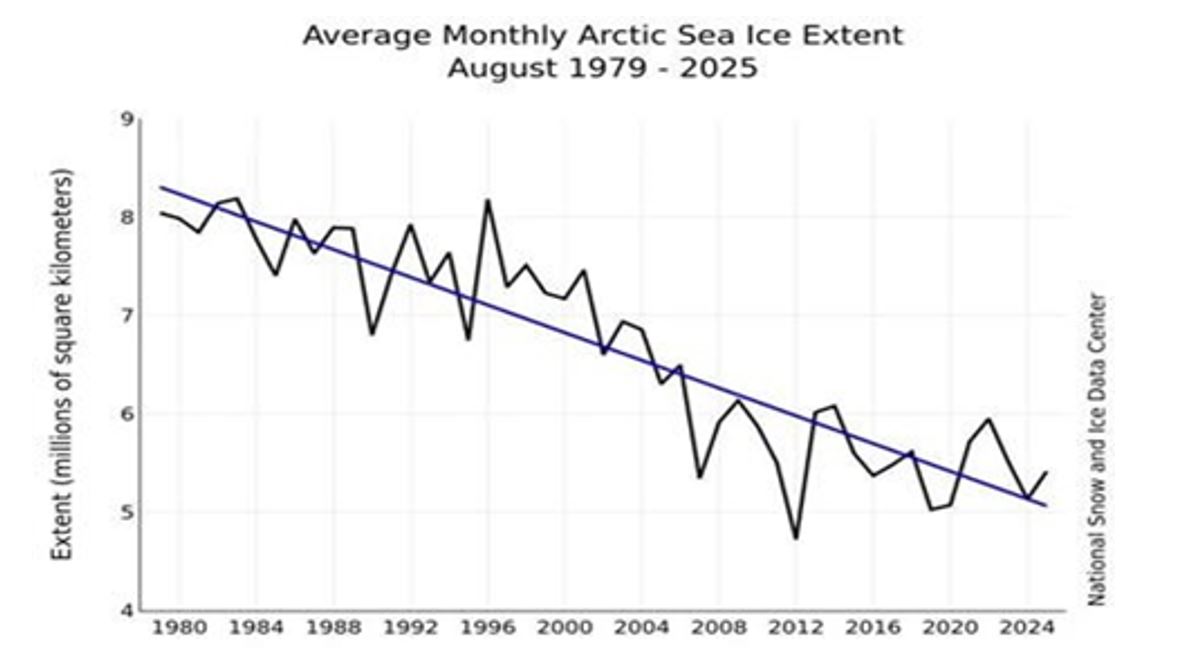

The quantity of ice on Earth is diminishing, both in the Northern and Southern hemispheres. The ice region in the north, commonly referred to as the Arctic, holds a substantial area of ice. According to data from the National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC), a US research institution supported by NASA, the sea ice area in the Arctic region recorded in August 2025 was 5.41 million square kilometers. However, a negative and significant impact that must be addressed in the near future is the yearly decreasing quantity of Arctic sea.

Recent NSIDC data further indicates a downward trend in the extent of Arctic sea ice in August 2025, specifically a reduction of 70,500 square kilometers per year, or a decline of approximately 9.8% per decade since 1980. Based on this established trend, the Arctic Ocean has lost a total sea ice area of 3.24 million square kilometers since 1979, an area equivalent to twice the size of Alaska in the United States. A depiction of the concerning trend found in NSIDC data on Arctic sea ice decline is illustrated in the graph below.

Reasons for Arctic Interest

The melting of ice in the Arctic region undeniably presents various negative consequences for the territories of numerous countries, particularly those geographically structured as archipelagic states, many of which are unfortunately situated along the equator. The continuous melting of Arctic ice, coupled with the strengthening of the Earth's magnetic pull, is anticipated to result in sea level rise in equatorial zone.[1]Furthermore, this phenomenon is expected to lead to coastal flooding, the accelerated erosion of shorelines, and the threat of displacement for coastal populations.

In contrast to the Arctic surrounding nations, which benefit from territories largely dominated by landmass, Indonesia as an archipelagic nation and is unequivocally in a vulnerable position concerning the effects of sea level rise caused by the melting of the Arctic polar ice. Consequently, Indonesia is compelled to become proactive in finding ways to safeguard its assets and minimize the associated geopolitical and economic implications.

Existential Threat: Arctic Ice Melt and Sea-Level Rise

The lost millions of square kilometers in ice area at the Arctic Pole inevitably constitutes a tangible contribution to the increase in sea volume. This increase in sea volume will certainly have consequences for coastal regions and nations formed with an archipelagic configuration.

According to the Arctic Council, over the last 10 years, the global sea level has risen approximately 1.5 times or 50% faster compared to the rate of global sea level rise in the 1990s. Specifically, from 1993 to 2002, the average global sea level rise was recorded at a level of 2.4 mm per year and increased even further in the period from 2014 to 2023, rising in the range of 3.6 mm per year. This increase in sea level highly affects equatorial nations, rising 30% higher than the global average sea level rise, with countries like the Philippines and Indonesia being the most significantly impacted locations.

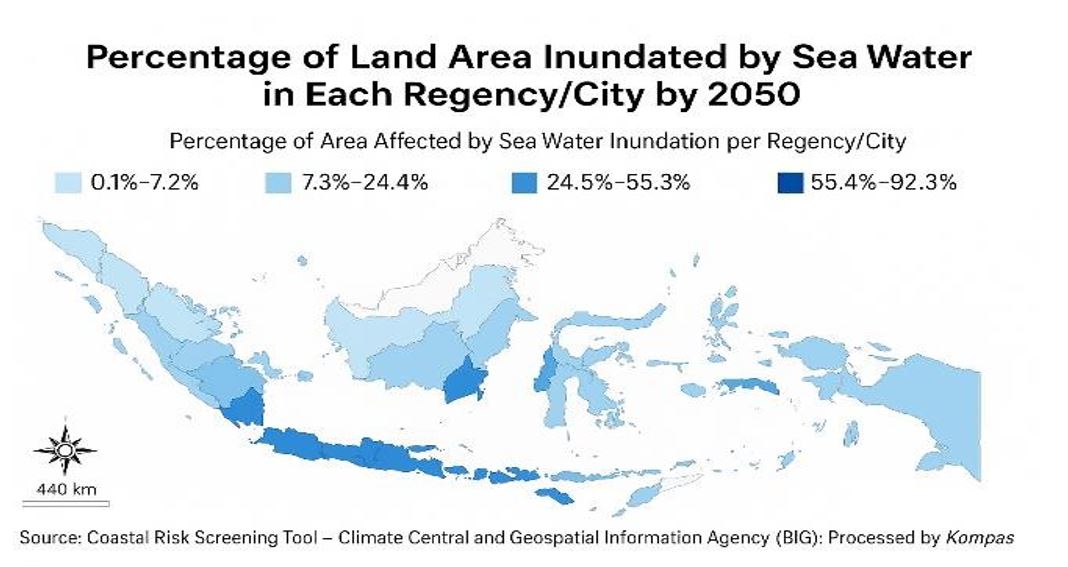

Indonesia, is experiencing an increase in sea level height of 0.9 to 1.2 cm per year due to the rising global sea level. Indonesia is also affected by temperature changes that have increased by 0.45–0.75 degrees Celsius. Furthermore, there is the vulnerability faced by Indonesia’s 18,000 km coastline, which is potentially susceptible to erosion by seawater. Several cities in Indonesia are already trapped in this situation. Jakarta, in the period of the years 2015–2023, has experienced an increase in sea level amounting to 1.65 cm. This is higher than the sea level rise in the area of Lautoka, Fiji Island tat rise around 0.91 cm, and the area of Honiara, Solomon Islands around 1.56 cm, but lower than the sea level rise in the area of Port Vila, Vanuatu around 1.91 cm.[2] Other cities, such as Tuban in the East Java region, are also receiving quite significant impacts. It is seen that in 2010, Tuban experienced a sea level rise as high as 0.297 m, which subsequently increased in 2020 to a level of 0.54 m, and the sea level is projected to increase in that city in 2030, at a level of 0.757 m.[3] By the year 2050, it is predicted that approximately 118,000 hectares of Indonesian territory will be inundated by seawater. This consists of 199 regencies and cities in Indonesia out of a total of 514 regencies and cities, and is spread across twenty-one provinces. Below is a depiction of the Indonesian regions most impacted by the predicted 2050 sea level rise.

Impact on Weather Systems and Food Security

Indeed, the impacts of melting Arctic ice and rising sea levels include increased global temperatures and climate change, establishing a mutually reinforcing feedback loop. According to Sean Fleming (2020) in the World Economic Forum, the global temperature has risen by approximately 1 degree Celsius per decade, or more, over the preceding 40 years (measured from the time of writing in 2020). Conversely, certain regions, such as the Barents Sea and the Svalbard archipelago in Norway, have experienced even higher temperature increases, rising by about 1.5 degrees Celsius per decade within the same period.

The resultant effects are predictably linked to the greenhouse effect, characterized by extreme and volatile weather changes. This includes increased precipitation in areas typically experiencing moderate rainfall, while other regions accustomed to high rainfall may observe a sharp decrease in intensity.[4] Deng and Dai,[5] demonstrate a high correlation between Arctic sea ice and the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle. Arctic sea ice is characterized as a natural dampening mechanism that helps maintain and regulate the predictability of the El Niño and La Niña cycles. The melting of Arctic ice threatens to weaken this dampening effect on both El Niño and La Niña, potentially pushing the two phases of the climate cycle into an unregulated, unstable state. Consequently, it is plausible that, in the future, El Niño events will become stronger, leading to more severe droughts, and La Niña events will intensify, resulting in heavier rainfall and more extreme flooding.

Climate uncertainty consistently poses unpredictable threats to a nation's economy, specifically in Indonesia. Dwikorita Karnawati, Head of the Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysics Agency of the Republic of Indonesia (BMKG), stated that rainfall intensity has increased by approximately 10%–20% across Southeast Asia, including parts of Indonesia. Conversely, other areas, particularly in the southern parts of Indonesia, have experienced a sharp decline in rainfall intensity. These shifts in rainfall patterns can cause droughts and severely disrupt agricultural productivity.

According to Sevina et al.,[6] the pattern of food security uncertainty originates from a decline in food production. Whether resulting from extreme rainfall intensity or extreme drought, this leads to production issues and subsequently a crisis in meeting the public's food demand. Further impacts include reduced nutritional intake among the populace due to minimal food availability, along with an increased prevalence of diseases and health disorders that affect overall nutritional status and public health. Each of the variables mentioned above can significantly harm the national economy.

India Considers Northern Sea Route Potential

Scientific Cooperation and Research

Odo Manuhutu, Deputy Assistant for Navigation and Maritime Safety at the Coordinating Ministry for Maritime Affairs, indicated that the Coordinating Ministry for Maritime Affairs od Republic of Indonesia is currently exploring an initiative to become a permanent observer country in the Arctic Council, with the explicit aim of gaining primary access to climate change research.

Indonesia's application process to become a permanent observer in the Arctic Council commenced in 2017 and has been followed by various steps, such as conducting focus group discussions to prepare the draft justification document outlining Indonesia's urgency, which also serves as a prerequisite for formal submission to the Arctic Council.[7] The key issues underpinning Indonesia’s motivation to attain permanent observer status include climate change, energy security, the future of shipping lanes, and critically, access to knowledge and research from firsthand sources.[8]

Currently, the Arctic Council comprises member states, including its 1996 founders—Russia, Canada, the United States, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland—as well as five other countries: Japan, China, India, Singapore, and South Korea, which joined as permanent observers in 2013. The sharing of such information from such a diverse body can help Indonesian government and society learn to be proactive in taking preventive steps to minimize the subsequent impacts resulting from the melting of ice in the Arctic region.

However, Indonesia can also acquire knowledge from various non-Arctic Council countries regarding their preventive measures to minimize the consequences arising from rising sea levels. Indonesia could learn from similar initiatives implemented by Germany, the Netherlands, and Japan. Alternatively, Indonesia can learn from the United Kingdom's structural initiatives, including the construction of sand dunes, sea walls, groynes, rock armor, and beach nourishment.[9]

The Maritime Challenge (Trade Routes)

Indonesia operates under a foreign policy framework named the Global Maritime Fulcrum (GMF), which functions as a conceptual structure positioning Indonesia as a central actor in regional and global maritime dynamics. The GMF policy itself stands upon five pillars,[10] focused on Indonesia's identity as a nation predominantly covered by water.

The first pillar emphasizes the restoration of Indonesia’s historical identity as a maritime nation, fostering a maritime culture. The second pillar centers the policy on the sustainable management of marine resources, ensuring intergenerational economic equity and food security managed through genuine integration by policymakers and executors. The third pillar concentrates attention on enhancing the quantity and quality of maritime infrastructure and connectivity. National integration through equitable development and expanding access to public services in maritime areas is a necessity under this pillar. The fourth pillar involves the strengthening of maritime defense as key to prioritizing sovereignty and territorial protection, aimed at preventing and countering both traditional and non-traditional threats. The final, fifth pillar advocates for maritime diplomacy and conflict resolution through soft power. Maritime diplomacy is considered crucial for resolving various disputes and potential conflicts without triggering escalation, allowing Indonesia to pursue its national interests without disruption and potentially gain support for its objectives.

However, the melting ice in the Arctic region opens a new path for global sea routes and logistics. Some research reveals that the Northern Sea Route (NSR) can reduce the travel distance between Europe and Asia by approximately 10 to 14 days compared to routes passing through the Suez Canal.

Undoubtedly, the opening of the potential Northern Sea Route slightly disrupts Indonesia's GMF policy, especially the second, third, fourth, and fifth pillar. The second pillar is heavily focused on economic matters. This could become a central issue for Indonesia because the NSR holds significant potential to diversify global shipping lanes and reduce trade volume in the Malacca Strait, which is a central point of the GMF policy and has served as a crucial shipping lane for centuries.

If to consider the third pillar, which focuses on maritime infrastructure and connectivity, and possible new sea routes, vessels travelling through the Northern route will eventually converge in the South China Sea. This development will inevitably place pressure on Indonesia's GMF infrastructure vision to be more innovative and to invest more substantially in that sector. The rationale for this pressure lies in the certainty that the Northern route will be navigated by specialized ice-breaking vessels, which naturally possess high maintenance requirements. Rather than simply being defeated and becoming a casualty of competition due to diversification, Indonesia would be better served by establishing facilities that remain niche and represent a blue ocean strategy, such as hangars for Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul (MRO).

Similarly, the fourth and fifth pillar, which concentrates on sovereignty, territorial protection, and diplomacy is also affected. Historically, the ASEAN region, and Indonesia specifically, has been situated along strategic sea lanes, which affords both ASEAN and Indonesia significant leverage and bargaining power in achieving their national interests. Referring once again to the sea route map, the establishment of new routes and the resulting diversification of alternatives will progressively diminish the bargaining power of both ASEAN and Indonesia over time. This development challenges the conceptual framework of Indonesia's GMF under the fourth and fifth pillar, compelling Indonesia to exert greater effort to maintain its leverage in the international arena.

Energy and Green Energy Diversification

After discussing the challenges Indonesia faces, this sub-chapter shifts the focus to the positive potential of the Arctic region. According to Elena Tracy of the WWF Global Arctic Program,22 the Arctic region contains an estimated 90 billion barrels of undiscovered oil, representing approximately 13 percent of the world's total oil reserves. Similarly, the Arctic region is estimated to contain about 30 percent of the world’s undiscovered natural gas reserves, constituting an enormous potential for hydrocarbon exploration.

However, from Indonesia's perspective, there is currently no disclosed information regarding interest or openness in either fossil energy exploration or cooperation with various parties beyond matters related to climate and clean or renewable energy. In the sector of clean and renewable energy, Indonesia has already established collaborations with several Arctic nations, including Norway, Iceland, Denmark, and Sweden. With Norway, Indonesia has a clean and renewable technology cooperation agreement, such as in hydropower, with an investment cost amounting to USD 20 billion. Similar cooperation exists with Iceland for the utilization and development of geothermal technology. Alongside Denmark, Indonesia has established the Joint Indonesian-Danish Energy Partnership Program (INDODEPP), which focuses on various areas of clean energy and targets zero emissions by 2060. Finally, Indonesia has partnered with Sweden under the framework of The Sweden-Indonesia Sustainability Partnership (SISP), which also focuses on achieving zero emissions and healthcare. The Arctic region provides opportunities for Indonesia in clean energy cooperation because various countries in the region have already utilized and adapted clean technology.

The Shipbuilding and Maritime Industry

Considering Indonesia’s opportunities to implement its conceptual framework, particularly in realizing the second through fifth GMF pillars, the country has not yet fully moved in this direction, as it currently remains focused on MRO in the defense and military sectors. However, this does not constitute an obstacle if Indonesia can recognize this opportunity sooner and get its head start among other ASEAN countries. Regions bordering the South China Sea and the Malacca Strait can be leveraged by Indonesia as strategic locations for the establishment of MRO shipyards for Northern route ice-class vessels.

The establishment of these MRO shipyards for Northern route vessels can be executed by state-owned enterprises such as PT. PAL Indonesia, the largest maritime manufacturing company in Indonesia. This conceptual initiative resides within the "blue ocean" domain, as other ASEAN countries have not yet conceived or adequately executed this idea. It is also crucial for Indonesia to adopt this idea as a preventive measure against becoming a victim of competition resulting from the diversification of Arctic shipping routes. Consequently, Indonesia can still maintain its bargaining and diplomatic leverage as a strategic nation, enabling it to achieve its national interests without fearing the erosion of its bargaining

Conclusion

The melting of Arctic sea ice poses a significant and multifaceted challenge to Indonesia, compelling it to adopt a proactive policy stance. Indonesia’s interest in the Arctic is unequivocally non-territorial, instead driven by existential vulnerability stemming from climate change and geo-economic necessity stemming from geopolitical shifts.

The climate imperative is the primary driver addressing this vulnerability. Data from the NSIDC indicates a continuous decline in Arctic sea ice extent, which contributes to global sea level rise that disproportionately affects equatorial regions, rising 30% higher than the global average. Furthermore, the loss of Arctic sea ice threatens to weaken the natural dampening mechanism of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle, leading to greater climate uncertainty, which, in turn, disrupts agricultural productivity and threatens national food security.

Several challenges and opportunities concerning the Arctic directly impact Indonesia’s foreign policy framework, the Global Maritime Fulcrum (GMF). The opening of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) creates three distinct pressures across the GMF's pillars:

-

Pillar II (Economy): The NSR threatens to diversify global shipping lanes, reducing trade volume and revenue from the traditionally critical Malacca Strait.

-

Pillar III (Infrastructure): The development compels Indonesia to innovate its maritime infrastructure, facing pressure to either compete directly or establish specialized facilities to service the unique needs of ice-breaking vessels that will traverse the new route.

-

Pillars IV & V (Sovereignty & Diplomacy): The diversification of global routes progressively diminishes Indonesia’s bargaining power and diplomatic leverage derived from its control over strategic chokepoints, challenging its ability to achieve its national interests.

Indonesia has responded to these challenges by pursuing a Blue Ocean Strategy across energy and industry sectors. The challenge of the Arctic's fossil fuel reserves (estimated at 90 billion barrels of oil and 30 percent of gas) has been redirected by Indonesia toward cooperation in clean and renewable energy with Arctic states like Norway, Iceland, Denmark, and Sweden. Additionally, the threat to maritime infrastructure has been countered by the conceptualization of a more comprehensive approach to the shipbuilding industry, focused on establishing specialized Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul (MRO) facilities for ice-class vessels, positioning Indonesia to get a head start in the sphere among ASEAN nations.

Recommendations

Based on the findings regarding the existential threats and strategic opportunities presented by the melting Arctic, the suggestions can prove to be critical in safeguarding Indonesia’s national interests and strengthening the Global Maritime Fulcrum:

1. Prioritize and Formalize Arctic Council Observer Status (GMF Pillar V)

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Coordinating Ministry for Maritime Affairs should accelerate the process of securing Permanent Observer Status in the Arctic Council. The primary objective must remain gaining access to cutting edge research and data related to climate and weather prediction (ENSO cycles) to enhance BMKG’s forecasting capabilities and improve national food security planning.

2. Strategic Investment in Blue Ocean MRO Infrastructure (GMF Pillar III)

The government, through state-owned enterprises (such as PT. PAL Indonesia), must immediately commit to developing specialized MRO and dry-dock facilities capable of servicing ice-class vessels. This investment must be integrated with the Green Energy Initiative (Pillar II), ensuring that these MRO hubs also serve as clean fuel bunkering stations (e.g., LNG or Green Ammonia), leveraging the clean technology partnerships established with Nordic countries. This strategic synergy transforms the MRO challenge into a value innovation opportunity.

3. Establish a Dedicated Arctic Climate Risk Fund (National Budget & Pillar II)

Given the predicted inundation of 118,000 hectares by 2050, the Ministry of Finance of Republic Indonesia must establish a specific Arctic Climate Risk Fund. This fund should finance strategic initiatives, drawing lessons from countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and Japan (Giant Sea Wall projects), or the United Kingdom (structural initiatives), to protect the most vulnerable 199 regencies and cities. This provides a concrete, measurable defensive policy against the physical effects of Arctic melt.

4. Leverage GMF Pillars IV & V for Maritime Diplomacy (Strategic Influence)

Recognizing the erosion of bargaining power due to the NSR, Indonesia must use its Diplomacy (Pillar V) to compensate. The government should use its MRO and clean energy opportunities as diplomatic incentives, offering preferential trade or service agreements to nations that actively cooperate with Indonesia on maritime security and counter-IUU fishing operations (Pillar IV), thereby maintaining its regional influence despite the diversion of global routes.

[1] Philipus Mikhael Priyo Nugroho et al., “Analisis Strategi Arktik Indonesia Berbasis SDGs Ke-13: Isu Penggunaan Jalur Perdagangan Maritim Kawasan Arktik,” Jurnal Hubungan Internasional 15, no. 2 (2022), https://e-journal.unair.ac.id/JHI/article/view/38987.

[2] Priska E. Lumban Batu, Heryoso Setiyono, and Yusuf Jati Wijaya, “Analisis Fluktuasi Muka Air Laut di Pesisir Kota Jakarta Kaitannya dengan Fluktuasi Muka Air Laut Global Tahun 2015-2023” (Analysis of Sea Level Fluctuation on the Coast of Jakarta City in Relation to Global Sea Level Fluctuation 2015-2023), Indonesian Journal of Oceanography (IJOCE) 7, no. 1 (February 2025), https://doi.org/10.14710/ijoce.v7i1.24931.

[3] Ayu Haristyana, Suntoyo, and Kriyo Sambodho, “Prediksi Kenaikan Muka Air Laut di Pesisir Kabupaten Tuban Akibat Perubahan Iklim” (Prediction of Sea Level Rise on the Coast of Tuban Regency Due to Climate Change), Jurnal Teknik ITS 1, no. 1 (September 2012), https://e-journal.its.ac.id/index.php/teknik/article/view/143854/10427.

[4] Mona Febriani Irma and Eva Gusmira, “Tingginya Kenaikan Suhu Akibat Peningkatan Emisi Gas Rumah Kaca di Indonesia” (High Temperature Rise Due to Increased Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Indonesia), JSSIT: Jurnal Sains dan Sains Terapan 2, no. 1 (February 2024).

[5] Jiechun Deng and Aiguo Dai, “Arctic sea ice–air interactions weaken El Niño–Southern Oscillation,” Science Advances 10, no. 13 (March 29, 2024), https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adk3990.

[6] Sevina Yushinta Anjani, Bagus Setiawan, and Sofi Ayu Nur Martasari, “Dampak Perubahan Iklim Terhadap Ketahanan Pangan Di Indonesia” (The Impact of Climate Change on Food Security in Indonesia), Jurnal Pendidikan Dan Ilmu Sosial 2, no. 3 (July 2024), https://doi.org/10.54066/jupendis.v2i3.1850.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Al Mukhollis Siagian, “Solusi Adaptif Dampak Kenaikan Muka Air Laut” (Adaptive Solutions to the Impact of Sea Level Rise), in Teknologi dan kearifan lokal untuk adaptasi perubahan iklim (Technology and Local Wisdom for Climate Change Adaptation), ed. Elza Surmaini, Lilik Slamet Supriatin, and Yeli Sarvina (Penerbit BRIN, 2023), https://doi.org/10.55981/brin.901.c720.

[10] Erwin S. Aldedharma, “Indonesia's Global Maritime Fulcrum and Its Perspective on Good Order at Sea,” Proceeding Jakarta Geopolitical Forum 8, no. 1 (2024), https://doi.org/10.55960/jgf.v8i1.261.

(votes: 11, rating: 4.82) |

(11 votes) |

Interview with Dr Jawahar Vishnu Bhagwat

Halal as the Staff of Life: “New” Growth Areas in Russian–Indonesian Trade TiesTrade and economic relations between Indonesia and Russia are in their honeymoon phase

The 75th Year of Bilateral Relations of Indonesia and Russia: What is Next?Indonesia joins BRICS not only shows that Indonesia remains steadfast in its free and active foreign policy but also demonstrates that Indonesia is a reliable partner for all parties