The great transformation, continuous transformation, changes in the balance of power, and shifts in alliances and systems are all stages and descriptions of the international order. They represent phases through which the international system moves. Yet this time the world is witnessing a major transformation not at the level of actors, ideologies, or even interests, but at the level of operation—the operation of the international system itself. This is not a shift in the balance of power but in the way power itself functions. Among the first major powers to recognize this transformation in the system’s operating logic is the Russian Federation.

The transformations underway in the African Sahel region can no longer be understood merely as a redistribution of influence among competing international powers; rather, they reveal a deeper change in the logic by which the international system itself operates. The issue is no longer who advances or retreats within a specific geopolitical arena, but how stability is produced within an international system whose rules are no longer capable of enforcing compliance in the form assumed by the post-Cold War model.

The Sahel represents less a traditional geopolitical arena of competition than an early laboratory for a broader transformation in the logic of the international system. It reveals that stability is no longer produced through imposing compliance with a unified set of rules but through managing plurality within complex sovereign environments, where adaptability and operational flexibility become decisive elements of international effectiveness. A number of strategic analyses suggest that this transformation is not limited to Africa but reflects a broader global trend toward a more pluralistic international system with greater balance among different centers of power.

The growing Russian presence in the Sahel carries a significance that extends beyond traditional geopolitical interpretation. Rather than viewing Russian movements merely as expansion into spheres of influence or investment in a strategic vacuum, they may be understood as a form of early adaptation to an emerging international logic. This logic is based on the assumption that international effectiveness no longer depends primarily on the ability to impose unified institutional and normative models, but on the ability to operate within environments characterized by multiple political and sovereign pathways.

The Russian approach in the Sahel has been marked by a high degree of operational flexibility and a focus on direct functional cooperation. Instead of linking security or economic partnerships to long-term institutional compliance trajectories, emphasis has been placed on negotiated arrangements that respond to specific priorities related to security, stability, and national sovereignty. This approach does not imply the absence of legal or political considerations, but it reduces reliance on normative enforcement as a precondition for cooperation. In an environment characterized by high political and institutional fluidity, this mode of engagement provides greater room for maneuver compared with approaches that assume the feasibility of reproducing ready-made normative stability models.

The great transformation, continuous transformation, changes in the balance of power, and shifts in alliances and systems are all stages and descriptions of the international order. They represent phases through which the international system moves. Yet this time the world is witnessing a major transformation not at the level of actors, ideologies, or even interests, but at the level of operation—the operation of the international system itself. This is not a shift in the balance of power but in the way power itself functions. Among the first major powers to recognize this transformation in the system’s operating logic is the Russian Federation.

The transformations underway in the African Sahel region can no longer be understood merely as a redistribution of influence among competing international powers; rather, they reveal a deeper change in the logic by which the international system itself operates. The issue is no longer who advances or retreats within a specific geopolitical arena, but how stability is produced within an international system whose rules are no longer capable of enforcing compliance in the form assumed by the post-Cold War model.

An analyst observing the period following the end of the Cold War will note that approaches to crisis management and stability-building were grounded in a central assumption: that the international system could produce stable order through the expansion of normative and institutional enforcement. Stability was treated as the product of a gradual process of alignment with a set of rules, institutions, and standards presumed to possess an inherent capacity to generate compliance. According to this conception, security, economic, and political cooperation were often tied to institutional and normative compliance trajectories aimed at reshaping political environments according to a single model of stability.

However, this assumption began to erode gradually. In environments characterized by multiple sources of legitimacy, contested sovereignty, and weak institutional capacity, imposing a unified normative model has proven incapable of producing stability in the manner assumed by earlier approaches. Literature on legitimacy in international relations indicates that compliance with rules does not necessarily result from their mere existence or imposition; rather, it depends on actors’ perceptions of their legitimacy and suitability to their political and social contexts (Hurd, 1999). As variation in sources of political legitimacy has increased and actors within many fragile environments have multiplied, the relationship between rule and compliance has become more complex and less amenable to control through traditional enforcement tools.

Moreover, the evolution of the concept of “norm contestation” in constructivist theory has shown that international rules function less as fixed commands than as references open to interpretation, negotiation, and adaptation (Wiener, 2014). Under conditions of such interpretive plurality, normative enforcement loses its capacity to function as an automatic mechanism for generating compliance and becomes instead one element within a broader negotiated process over the meaning of rules and the limits of their application. Rather than leading to the collapse of the international system, this development alters the way it operates, as the system persists through the management of differences rather than their final resolution.

Within this transformation, international stability is no longer understood as the direct result of imposing a unified normative model; instead, it has become the product of actor capacities to operate within environments characterized by multiple political and normative pathways. This may be described as a gradual transition from a model based on normative enforcement to one based on managing plurality within a more fluid and complex global system. A number of contemporary Russian strategic analyses suggest that the international system is moving toward a phase in which the capacity of any single center to monopolize the definition or imposition of rules is declining, alongside the rise of more flexible models based on plurality and balance among different centers of power (Lukyanov, 2023).

In this sense, the ongoing transformation does not signal the collapse of the international system but the reconfiguration of its operating logic. Rules and institutions do not disappear; rather, they lose their capacity to function as mechanisms of immediate enforcement and instead become negotiated frameworks used to manage interactions within an international environment marked by high levels of sovereign and normative plurality. In such an environment, international effectiveness is no longer measured solely by the ability to impose compliance but by the capacity to operate within this plurality without assuming the possibility of eliminating or forcibly unifying it.

The African Sahel as a Laboratory for Global Transformation

The transformation in the logic of the international system has begun to take shape gradually over the past two decades. As a testing ground, the African Sahel is among the clearest arenas in which its practical features are visible. The transformations witnessed in the region in recent years cannot be explained merely as a redistribution of influence among external powers; rather, they reveal a deeper change in the conditions under which stability is produced and in how international actors operate within environments marked by high political and normative fluidity.

For decades, international engagement in the Sahel relied on a model that assumed sustainable stability required rebuilding the state and its institutions through gradual compliance trajectories tied to specific political, security, economic, and even historical (colonial) reforms. Security and military cooperation and development support—particularly from European powers—were linked to conditionality frameworks aimed at aligning local institutions with a set of political and administrative standards considered essential for achieving long-term stability. Yet the operational environment in the Sahel began to change gradually with the escalation of security threats, growing social and economic pressures, and increasing political fragmentation within several states.

Under these pressures and changes, the capacity of traditional normative enforcement tools to produce stable outcomes declined. Political sanctions, diplomatic pressure, and institutional conditionality were no longer capable of imposing long-term compliance trajectories in environments characterized by weak institutional capacity and multiple sources of political legitimacy. Indeed, attempts to impose specific institutional models often led to continuous renegotiation over the nature of the state, the limits of sovereignty, and security priorities, rendering the relationship between international rules and local implementation more complex and less controllable.

Mali and Niger serve as examples of these transformations. Political and security developments in recent years have revealed the limits of a stability model based on normative conditionality. In Mali, escalating security threats and repeated political transitions prompted a comprehensive reassessment of the nature of international security partnerships. As approaches based on long-term institutional enforcement proved less effective, the need emerged for more flexible arrangements capable of responding simultaneously to immediate security requirements and political sovereignty. In Niger, recent political shifts revealed the fragility of the balance between internal security considerations and external normative pressures, prompting a redefinition of the nature and conditions of international engagement.

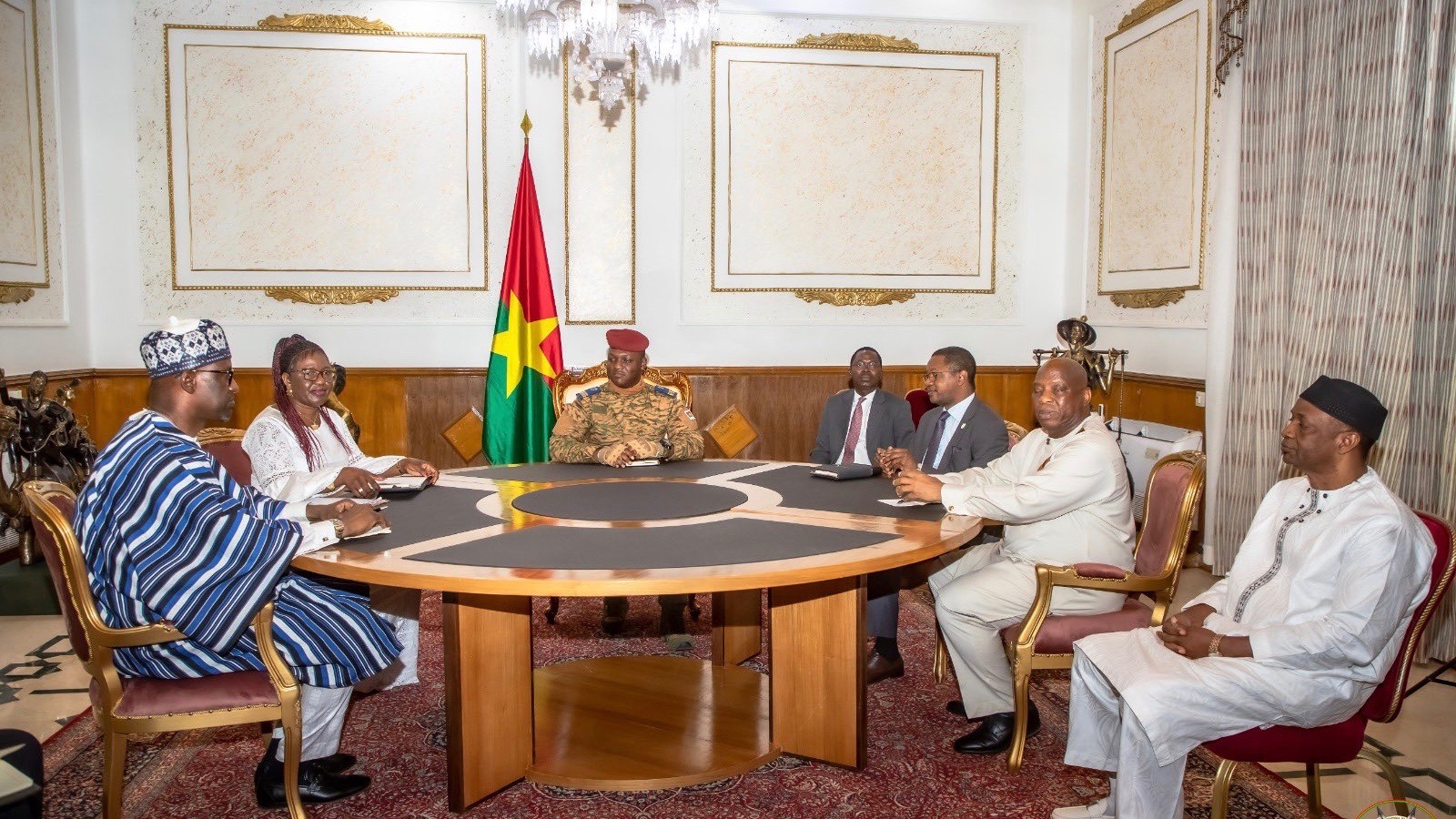

These transformations should not be viewed in isolation but rather as a mobile operational pattern across the entire region, as also evident in Burkina Faso. They are therefore not individual cases but part of a broader operational model extending beyond a single state.

These developments do not merely reflect the decline of one international power and the rise of another; they indicate a change in the environment within which all powers operate. In an environment characterized by multiple sources of legitimacy and shifting priorities of national sovereignty, imposing a unified normative model becomes more difficult and politically costly. Instead, the success of international actors is determined by their capacity to operate within this plurality and adapt to political and institutional environments that do not allow for the reproduction of ready-made stability models.

Thus, the Sahel represents less a traditional geopolitical arena of competition than an early laboratory for a broader transformation in the logic of the international system. It reveals that stability is no longer produced through imposing compliance with a unified set of rules but through managing plurality within complex sovereign environments, where adaptability and operational flexibility become decisive elements of international effectiveness. A number of strategic analyses suggest that this transformation is not limited to Africa but reflects a broader global trend toward a more pluralistic international system with greater balance among different centers of power (Trenin, 2024; Sakwa, 2017).

Russia and the Logic of Early Adaptation to a Transforming International System

Here emerges a traditional question, but its answer in this article differs: who fills the vacuum?

The growing Russian presence in the Sahel carries a significance that extends beyond traditional geopolitical interpretation. Rather than viewing Russian movements merely as expansion into spheres of influence or investment in a strategic vacuum, they may be understood as a form of early adaptation to an emerging international logic. This logic is based on the assumption that international effectiveness no longer depends primarily on the ability to impose unified institutional and normative models, but on the ability to operate within environments characterized by multiple political and sovereign pathways.

The Russian approach in the Sahel has been marked by a high degree of operational flexibility and a focus on direct functional cooperation. Instead of linking security or economic partnerships to long-term institutional compliance trajectories, emphasis has been placed on negotiated arrangements that respond to specific priorities related to security, stability, and national sovereignty. This approach does not imply the absence of legal or political considerations, but it reduces reliance on normative enforcement as a precondition for cooperation. In an environment characterized by high political and institutional fluidity, this mode of engagement provides greater room for maneuver compared with approaches that assume the feasibility of reproducing ready-made normative stability models.

One might ask whether this is merely political pragmatism.

The answer has two dimensions. First, some Russian analyses suggest that this approach reflects an early awareness of the transformation in the structure of the international system, in which the capacity of any single model to impose itself as the only possible formula for stability is declining (Karaganov, 2024). In such a system, the ability to adapt to sovereign and normative plurality becomes a fundamental element of international effectiveness. This does not mean that Russia seeks to build a fully formed alternative order; rather, it indicates that it is operating within a system undergoing reconfiguration, where managing plurality rather than imposing uniformity becomes the primary rule of international practice.

Second, in this sense, the Russian presence in the Sahel represents not merely an expansion of influence but a different pattern of exercising international effectiveness. It is based on reducing reliance on normative conditionality and increasing focus on flexible negotiated partnerships that take into account the specificity of local contexts. In an environment where normative enforcement can no longer automatically produce stable order, this mode of engagement offers greater capacity for continuity and adaptation. A number of analysts view this orientation as reflecting a gradual transition toward a more pluralistic international system in which balance among different centers of power becomes increasingly important and the capacity of any single actor to monopolize the definition or imposition of legitimacy declines (Lukyanov, 2023).

Implications of the Transformation for the International System

The transformations clearly visible in the Sahel region reveal a broader change in the structure and operating logic of the international system. This change does not occur through sudden collapse or abrupt transition from one order to another, but through a gradual reconfiguration of the mechanisms for producing stability and managing international relations within environments characterized by multiple sovereignties and sources of legitimacy. In such a context, the central question is no longer how a single model of order can be imposed, but how a degree of regularity can be maintained within a global environment marked by increasing political and normative plurality.

As the capacity of normative enforcement to function as a primary regulatory tool declines, international interactions move toward more flexible formats based on negotiation, adaptation, and the management of difference. This does not mean the disappearance of rules or institutions but their redeployment within a more pluralistic framework, where rules function as references for coordination and justification rather than commands capable of automatic imposition. Contemporary debates on multipolarity suggest that the international system is entering a phase in which the ability of a single center to monopolize the definition or imposition of legitimacy is diminishing, alongside the rise of more flexible balances among major powers (Sakwa, 2017).

What the world is witnessing today is not a transition to multipolarity in the traditional sense but to operational plurality, where plurality of poles appears in the operation of the international system rather than merely in its actors.

Within this transformation, the meaning of international effectiveness is being redefined. The ability to impose unified institutional or political models is no longer the sole indicator of influence; effectiveness now depends on the capacity to operate within multiple contexts without assuming the possibility of forcibly unifying them. A number of Russian strategic analyses suggest that the international system is moving toward a phase in which plurality and balance among centers of power become increasingly important, and maintaining stability depends on managing interactions among different political and normative systems rather than attempting to merge them into a single model (Trenin 2024; Lukyanov, 2023)

Accordingly, approaches based on operational flexibility and adaptation to sovereign plurality are gaining importance. In its current phase, the international system is not moving toward chaos so much as toward a new form of organization based on balance among multiple pathways to stability. This means that the ability to operate within changing and complex environments becomes a decisive factor in determining the position of international actors within the emerging global order.

Conclusion: Russia and the Great Transition

The transformations unfolding in the African Sahel extend beyond the region to signal a broader trajectory in the evolution of the international system. The Sahel is not merely a geopolitical arena of competition but reflects a transitional phase in which the logic of producing global stability is changing. In an environment where rules can no longer automatically impose compliance, the international system is moving toward a model based on managing plurality rather than attempting to resolve or eliminate it.

Here the Russian role within this transformation appears not as geopolitical rivalry or traditional power competition but as an expression of early adaptation to an emerging international system. Moscow is not moving solely to expand its presence in new regions; it is acting with a growing awareness that international effectiveness in the coming phase will depend on the capacity to operate within a plural global system in which no single model of stability or legitimacy can be imposed. By adopting approaches based on flexibility, negotiation, and respect for sovereign plurality, Russia contributes to shaping a new pattern of international effectiveness consistent with the features of the emerging global order.

This transformation does not signal the end of international rules or institutions but their reformulation within a more pluralistic and complex environment. The international system is not collapsing; it is reorganizing itself around new balances that reflect the reality of political and sovereign plurality in the contemporary world. As this trajectory continues, the contours of the coming global order will be determined by the capacity of major powers to adapt to the logic of plurality rather than seeking to transcend it.

In this context, Russia appears as one of the powers that has begun early to recognize the nature of the ongoing transformation and to act in accordance with its logic. It is not merely seeking to expand its influence within an existing system but is redefining the logic of international effectiveness itself, operating within a system undergoing reconfiguration in which the capacity to manage plurality and maintain balance among different centers of power becomes the foundation for producing international stability. From this perspective, Russian movements in the Sahel do not represent merely regional expansion but reflect an advanced position within the great transformation reshaping the logic of the international system in the twenty-first century.

References

1. Hurd, Ian. (1999). Legitimacy and Authority in International Politics. International Organization, 53(2), 379–408.

2. Wiener, Antje. (2014). A Theory of Contestation. Springer.

3. Sakwa, Richard. (2017). Russia Against the Rest: The Post-Cold War Crisis of World Order. Cambridge University Press.

4. Lukyanov, Fyodor A. (2023). Between Two Special Operations. Russia in Global Affairs, 21(2), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.31278/1810-6374-2023-21-2-5-10

5. Karaganov, Sergei A. (2024). An Age of Wars? Article Two. What Is to Be Done. Russia in Global Affairs, 22(2), 96–111. https://doi.org/10.31278/1810-6374-2024- 22-2-96-111

6. Trenin, Dmitry. (2024, May 3). “Third Decade of the 21st Century Promises to Be Very Turbulent”: On a New Global Order and Its Nuclear Dimension. Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC).