The final and long-awaited decision to deploy the U.S. THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) mobile missile defence complexes in South Korea was announced on July 8. The stationing of these purely defence systems, which are ideally suited for the Korean theatre of military operations-to-be, has been met with strong criticism from the Chinese and Russian missions, with experts accusing the United States of spurring on the arms race in the peninsula. Why is this?

The US Army’s THAAD complex was developed following the First Gulf War in 1991, when the standard air defence system Patriot performed dismally in the task of intercepting Iraq’s Al-Hussein ballistic missiles, which were basically Soviet R-17s with an increased range [1]. One of the problems revealed in the use of the Patriot System was the low effectiveness of its fragmentation warheads against fairly large ballistic missiles. Even an indirect hit (the explosion of the warhead at a distance from a plane – which is what anti-aircraft missiles are supposed to do) did not guarantee that the target missile would be disabled; instead, owing to its speed and size, the missile would continue on its trajectory, sometimes even with a still-functioning warhead, and at best would only be deflected from its course. Increasing the power of the warhead is a possible solution, but it would significantly increase the mass and size of the missile: thus, in the Russian S-300VM complex (exported as Antey-2500), the tracked launcher, which carries the “large” 9М82М missiles and is designed to hit medium-range ballistic missiles, carries only two missiles. This poses certain problems in repelling a massive missile attack.

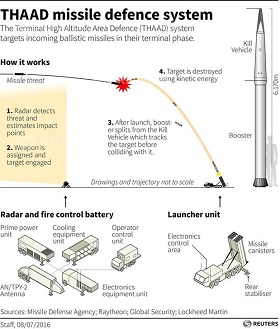

Another solution is kinetic intercept (often referred to as hit-to-kill in the West), that is, when an intercept missile directly hits the targeted ballistic missile. In this case, the interceptor has no need for a warhead because a head-on collision at a combined speed of over 5 km/sec assures the destruction of the target. However, the challenge is to ensure a direct hit on a relatively small target at what is practically escape velocity. To this end, the THAAD missile is fitted with an infrared self-targeting system at the final stretch (most air defence missiles are ground-targeted and are provided with thrusters). Because the missile is small, one THAAD launch vehicle carries eight missiles. Though its exact specifications are secret, they are known to be able to hit ballistic missiles at a range of more than 200 kilometres. It is thought that the range of radar detection, speed, altitude and manoeuvrability of the intercept missiles means they are effective against ballistic missiles with a range of up to 5500 kilometres.

A distinctive feature of THAAD is that it is intended to intercept missiles before they enter the atmosphere. This is declared to be highly safe for the facilities that are being protected, but the real aim is probably to “close” the gap in the layered missile defence between the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense System and the Patriot.

The difficulty of using kinetic interceptors for high-speed medium-range ballistic missiles at a long distance created problems in the building of the THAAD system. While flight tests began in 1995, it was not until 1999 that Lockheed Martin, the general contractor, successfully intercepted the target. Although further tests were more successful – the corporation’s website speaks proudly of its 100 per cent success rate since 2005, including 11 successful intercepts out of 11 – the complex was still not ready by the time of the Second Iraq War. The First Battery officially received THAADs in May 2008. The United States bought a total of seven batteries, of which six have been handed over to the client. Each battery includes an AN/TPY-2 radar, three launchers, a command post and 24 interceptor missiles.

Lockheed Martin proposed the development of the THAAD ER (Extended Range) complex with a larger diameter of the booster stage. THAAD ER is expected to have a longer intercept range (meaning it will cover a larger area) and to be able to cope with actively manoeuvring targets, such as the warheads of DF-21D or Iskander missiles. The price of the increased size will be the reduction of the number of missiles to five per launcher. Although it looks promising, there is currently no active funding for the development of THAAD ER.

The Right Place at the Right Time?

After the fall of the Saddam Hussein regime, North Korea and Iran automatically became the main opponents of THAAD, as the two countries were actively pursuing missile programmes themselves. The Iranian threat prompted the United Arab Emirates and Oman to purchase the missiles in 2011 in 2013, respectively (the orders have yet to be fulfilled). North Korea, of course, did not go unnoticed – the U.S. Army battery was operationally deployed for the first time in April 2013 on the Island of Guam in the Western Pacific. It is still on duty there, covering the U.S. strategic aviation airfield on the island. Potentially, the island is within striking distance of Korean Musadan MRBMs, and THAAD, along with Aegis-carrying ships, is the only asset that has a chance of intercepting these missiles. South Korea, of course, is also interested in buying U.S. missile complexes. The purchase and deployment of American missiles was actively discussed in 2013–2014, but, in the end, the Koreans chose to start developing a missile complex of their own (L-SAM), which is expected to be completed by 2023–2024.

THAAD is a bit excessive for the South (the country’s size means that it is threatened by shorter-range missiles). On the other hand, the capacity of its RAS-3 missiles (also a modification of the Patriot prompted by the experience of the 1991 war) is very limited. The compact hit-to-kill missile is unsuited for protecting a large territory since it can only intercept a ballistic target within a range of 15–20 kilometres [2]. The worsening of relations between the United States and South Korea, on the one hand, and North Korea, on the other, in early 2016 predictably rekindled interest in deploying American THAAD on Korean territory. Purchasing these complexes is not the best option, because, first of all, the process takes years and, secondly, South Korea is building its L-SAMs, which are tailor-made for its own needs, its armed forces and the defence industry.

Eventually, after six months of talks and tough debates, mainly with the Chinese side, the decision was announced on July 8 to deploy THAAD on Korean territory the following year. The missiles will be deployed in the southeast of Seongju County. Interestingly, Seongju is in the south of the country, which, critics say, makes it physically incapable of intercepting missiles targeting Seoul. On the other hand, such a location enables it to protect important logistical facilities, and helps to defend Okinawa. Thus, it is intended to protect the targets that are the most important for long-range North Korean missiles, while Seoul (a megalopolis that can only be catastrophically damaged by weapons of mass destruction), will be covered by “small” RAS-3 missiles intended for that purpose. Besides, the locality chosen is sparsely populated, which would attract less attention on the part of local opponents of deploying the THAAD system, who warn of harmful radiation from its radar – which just so happens to be the primary target.

Where Good Resolutions Lead

Why, then, did the strictly defensive and retaliatory move provoke such an angry reaction from China and Russia? Because it is not quite defensive and, to put it mildly, does not increase security on the peninsula.

As regards mutual nuclear deterrence (this Cold War concept can be observed in miniature on the Korean Peninsula today), there is much about it that defies the traditional definition. The defence systems, notably BMD, while protecting one side, diminish the deterrent potential of the other. Given a high-quality BMD, there may be a temptation to strike first, in order to destroy the bulk of the strategic nuclear force, and then try to beat off a retaliatory strike. Deploying a single THAAD battery is not enough to neutralize the threat of North Korea’s Strategic Rocket Forces [3]. At best, it can counter a local strike, for example, in one of the unusually excessive “exchanges of fire” that occur from time to time between North and South. After all, the North has more than two dozen missiles. However, by beefing up its defence, the U.S.–South Korean side automatically pushes North Korea to develop its own offensive potential, because it will now have to expect some of its missiles to be shot down. Reports have already come in that North Korea is planning more nuclear tests. Even if they do not take place (the tension they would provoke is highly undesirable), aggressive rhetoric will certainly be ratcheted up and missile tests will become more frequent. This is hardly conducive to promoting calm in the region, let alone a resumption of the dialogue between the two Koreas.

China has been particularly critical of the deployment of AN/TPY-2 radars, because they can potentially be used to spy on its own territory and undermine its own security. The United States and South Korea have declared that the radars will be deployed in terminal mode, which will ensure targeting of THAAD interceptor missiles and detection within a range of 600–900 kilometres. However, the Chinese side is worried that they can be refitted into a forward-based mode, in which the detection range would be increased to 2000 kilometres and much of China’s territory would be observable. It is unclear how much time “mode switch” takes.

The problem, however, seems to be partly imagined. First, Japan has had two such radars since the end of 2014. And, in the absence of missile systems, they have probably been used in the forward-based mode and observe much of China’s territory. Second, for reconnaissance purposes, the Americans can always send specialized ships and planes to Chinese shores, and in the event that a conflict threatens to develop into a nuclear war (not a very likely situation), it can move these radars, which were designed to be air-transportable, wherever necessary.

Besides, Seongju, which is located quite far from the border, was likely chosen as the site so as to minimize China’s ire. What seems to worry the Chinese side most is the legitimate fear that THAAD may be only the beginning, and that North Korea’s inevitable reaction would legitimize the United States increasing its military infrastructure on the peninsula.

Besides, as a neighbour, China has no desire to see the situation get any worse. On the other hand, the United States has no problem with the North Korean regime presenting itself in the world media as an aggressive militaristic regime with its missile and nuclear tests, as well as its defence spending, which eats up huge resources that could otherwise be used to continue economic reform. In doing this, North Korea merely justifies the shift of focus of the U.S. military might to the Pacific region. However, North Korea may itself try to derive some benefit from what is happening, since a spat between the United States and China may prompt the latter to sabotage the recently introduced tough sanctions, which, like any other economic restrictions imposed on North Korea, depend on the position that China takes.

For Russia, the situation is unpleasant first and foremost because this most recent crisis on the Korean Peninsula does not seem to be fading gradually. On the contrary, it continues to be fanned, and what is more, it is being fanned to a large extent by external forces. Again the forecast is pessimistic: after the official announcement that the resistance from China and inside South Korea has been overcome, backtracking would be a criminal show of weakness. So we can be sure that THAAD complexes will be deployed in South Korea with much fanfare next year (and perhaps sooner if the North provides a pretext). The consequences are unpredictable, but certainly they are not going to be positive.

For Russia, the situation is unpleasant first and foremost because this most recent crisis on the Korean Peninsula does not seem to be fading gradually. On the contrary, it continues to be fanned, and what is more, it is being fanned to a large extent by external forces.

Again the forecast is pessimistic: after the official announcement that the resistance from China and inside South Korea has been overcome, backtracking would be a criminal show of weakness. So we can be sure that THAAD complexes will be deployed in South Korea with much fanfare next year (and perhaps sooner if the North provides a pretext). The consequences are unpredictable, but certainly they are not going to be positive.

A worrisome symbolic signal is sent by current reports that the demilitarized zone between the two Koreas has officially ceased to exist, and that the two sides are pouring previously banned heavy weaponry into the border area.

1. In the United States, these systems are subordinate to the ground forces.

2. Used in the PAC-3 system, the ERINT extended range interceptor weighs in at just over 300kg. The Patriot carries 16 of them, instead of the original four. However, their low range means that they have to be used for shooting aerodynamic targets with older modifications.

3. Just like the U.S. continental missile defence system, which only has around 40 that are capable of bringing down ICBMs, Ground-Based Interceptors, it cannot neutralize the potential of China’s strategic nuclear weapons, not to mention those of Russia.