AI Nationalism and AI Nationalization Are ahead

(votes: 7, rating: 4.86) |

(7 votes) |

Founder and Chief Technology Officer, Witology, Chairman of Board of League of Independent Experts, RIAC Expert

Technological inequality has always had a major impact on global politics and the world economy. The most technologically advanced states became the most successful, gained undisputed military superiority and begin to impose their will onto less developed countries.

In the 20th century, two world wars and the extraordinary acceleration of scientific and technological progress made this impact even greater. With the third decade of the 21st century approaching, the avalanche-like growth of machine learning capabilities has forced us to talk about the spectrum of IT technologies, unified by the metaphorical term “Artificial Intelligence” (AI) as the key factor in economic, geopolitical and military power of the coming decades.

2018 marked a watershed. Previously, when the media, society and politicians discussed the future challenges and dangers of AI development, they focused on:

— cognitive AI agents (robots and software) supplanting people in many professions;

— the legal and ethical problems of autonomous AI devices (for instance, driverless cars);

— cybersecurity issues;

— the frighteningly alluring prospect of a “revolt of the machines” in the distant, or perhaps not so distant future.

However, things began to change in 2018. The above-listed threats and challenges did not exactly disappear, but rather faded into the background as politicians and the military became aware of the global transformational trends that can be provisionally termed

— AI nationalism

— AI nationalization

These trends were highlighted by the fact that, in drafting their national AI strategies, many developed countries simultaneously started to change their attitudes towards two basic principles that had previously seemed unshakeable:

— instead of comprehensive international cooperation, the global division of labour, the introduction of open platforms and the mutual overflow of talent, countries are now placing an emphasis on AI nationalism, which proclaims the priority of the economic and military interests of one’s own country as the principal objective of its national AI strategy;

— instead of the separation of state and business that is traditional for many countries, the course has been set for AI nationalization, i.e. integrating governmental and private resources, aligning the pace of introducing AI innovations and refocusing strategic objectives on the state gaining economic, geopolitical and military advantages in the international arena.

The strengthening of these trends promotes the shift of state priorities in developed countries away from the economy and towards geopolitics. If this trend continues, the world will undergo major changes in the near future.

AI as a Geopolitical Factor

Technological inequality has always had a major impact on global politics and the world economy. The most technologically advanced states became the most successful, gained undisputed military superiority and begin to impose their will onto less developed countries.

In the 20th century, two world wars and the extraordinary acceleration of scientific and technological progress made this impact even greater. With the third decade of the 21st century approaching, the avalanche-like growth of machine learning capabilities has forced us to talk about the spectrum of IT technologies, unified by the metaphorical term “Artificial Intelligence” (AI) as the key factor in economic, geopolitical and military power of the coming decades.

2018 marked a watershed. Previously, when the media, society and politicians discussed the future challenges and dangers of AI development, they focused on:

— cognitive AI agents (robots and software) supplanting people in many professions;

— the legal and ethical problems of autonomous AI devices (for instance, driverless cars);

— cybersecurity issues;

— the frighteningly alluring prospect of a “revolt of the machines” in the distant, or perhaps not so distant future.

However, things began to change in 2018. The above-listed threats and challenges did not exactly disappear, but rather faded into the background as politicians and the military became aware of the global transformational trends that can be provisionally termed

— AI nationalism

— AI nationalization

These trends were highlighted by the fact that, in drafting their national AI strategies, many developed countries simultaneously started to change their attitudes towards two basic principles that had previously seemed unshakeable:

— instead of comprehensive international cooperation, the global division of labour, the introduction of open platforms and the mutual overflow of talent, countries are now placing an emphasis on AI nationalism, which proclaims the priority of the economic and military interests of one’s own country as the principal objective of its national AI strategy;

— instead of the separation of state and business that is traditional for many countries, the course has been set for AI nationalization, i.e. integrating governmental and private resources, aligning the pace of introducing AI innovations and refocusing strategic objectives on the state gaining economic, geopolitical and military advantages in the international arena.

The strengthening of these trends promotes the shift of state priorities in developed countries away from the economy and towards geopolitics. If this trend continues, the world will undergo major changes in the near future.

The Ethical and Legal Issues of Artificial Intelligence

A Brief Technological and Geopolitical Forecast

First, the geopolitical and military doctrines of most developed countries are going to change. Many economic and political processes brought together under the term globalization will undergo radical transformations. It is possible that AI technologies will put an end to globalization, a trend that has been picking up pace following the fast technological development that came after World War II. And then global Balkanization will replace globalization.

Second, the change in the model of co-existence of the state and business will have an equally profound impact. The integration of the goals and resources of the state and private businesses in order to achieve military superiority will most likely result in the global triumph of the authoritarian-democratic model that China has already added to its armoury, both literally and figuratively.

As a result, international relations will be determined by the following key factors:

— AI neo-colonialism in relations between AI leaders and outsiders;

— An AI arms race between the leading countries that will guide and determine subsequent development of AI technologies.

Such race could have two possible outcomes:

A. “World War III,” after which World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.

B. The “AI Singularity,” where the development of AI technologies, spurred on by the arms race, will end up generating a “strong AI” that will remove the opposing parties as unnecessary.

The first option appears to be the most probable, with the second option also being a possibility.

It is important to note that, at some point, the AI nationalism and AI nationalization trends will be driving their own development. As with any other arms race, the pace and strength of these trends will no longer depend on the degree of AI progress. And even if AI progress turns out to be more modest than expected, the gigantic inertia of both trends will require much time and effort to be overcome.

2018: The Year of the Great AI Watershed

After the end of the Cold War, the United States held a virtually unsurpassed superpower status. The crucial factor was its unrivalled military and technological superiority. Nonetheless, technologies that had previously formed the foundation of the country’s military defense, such as high-precision weapons, have spread throughout the world due to globalization and technology transfer. As a result, the rivals of the United States have developed their own capabilities that offer a progressively greater challenge to U.S. military superiority.

To retain and expand its military edge in future, the U.S. Department of Defense banked on AI technologies, the potential military use of which is highly diversified: from improving efficiency of logistical systems to more sensitive tasks, such as automated control and monitoring in modern weapons systems. The 2018 National Defense Strategy proceeds on the assumption that AI will mostly likely change the nature of warfare. That is why U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan states that the United States “must pursue AI applications with boldness and alacrity” [14].

There are grounds to believe that the U.S. government has finally heard Eric Schmidt, former head of Google and Alphabet, who called upon it last year to realize that the “Sputnik Moment” in AI had already arrived.

Secretary of Defense James Mattis called upon President Trump to draft a national artificial intelligence development strategy both for the U.S. government and for the entire country. Mattis’ letter to the President contained a suggestion on the establishment of a presidential committee capable of “inspiring a whole of country effort that will ensure the U.S. is a leader not just in matters of defense but in the broader ‘transformation of the human condition.’”

In response to those statements,

— The “Summary of the 2018 White House Summit on Artificial Intelligence for American Industry” states that “the Trump Administration has prioritized funding for fundamental AI research and computing infrastructure, machine learning, and autonomous systems”;

— on July 31, 2018, the White House released Memorandum No. M-18-22: FY 2020 Administration Research and Development Budget Priorities [15] naming AI the top of three national technological priorities (followed by quantum informatics and supercomputing, respectively) and mandated that the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) jointly with the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) ensure top budgeting priority for these areas in all federal agencies in 2019–2020.

It so happened that it was not just the U.S. government that experienced a “Sputnik Moment” in 2018.

The number of countries announcing national AI development strategies more than tripled compared to 2017.

In 2017, AI enthusiasts (Japan, Canada and Singapore) inaugurated the marathon of signing national AI strategies. The trio was followed by China, one of the two claimants to global AI leadership, which deployed its main financial weapon.

Now, in 2018, it is much easier to pinpoint those who have not yet publicized their national AI strategy, since the United Kingdom, Germany, France and a dozen more countries have already presented theirs. As it should have been expected, different countries have set forth different goals and approaches in their national AI strategies.

The strategies that have been drafted upon the instructions of national governments are also different in length and the degree of their elaboration and detail.

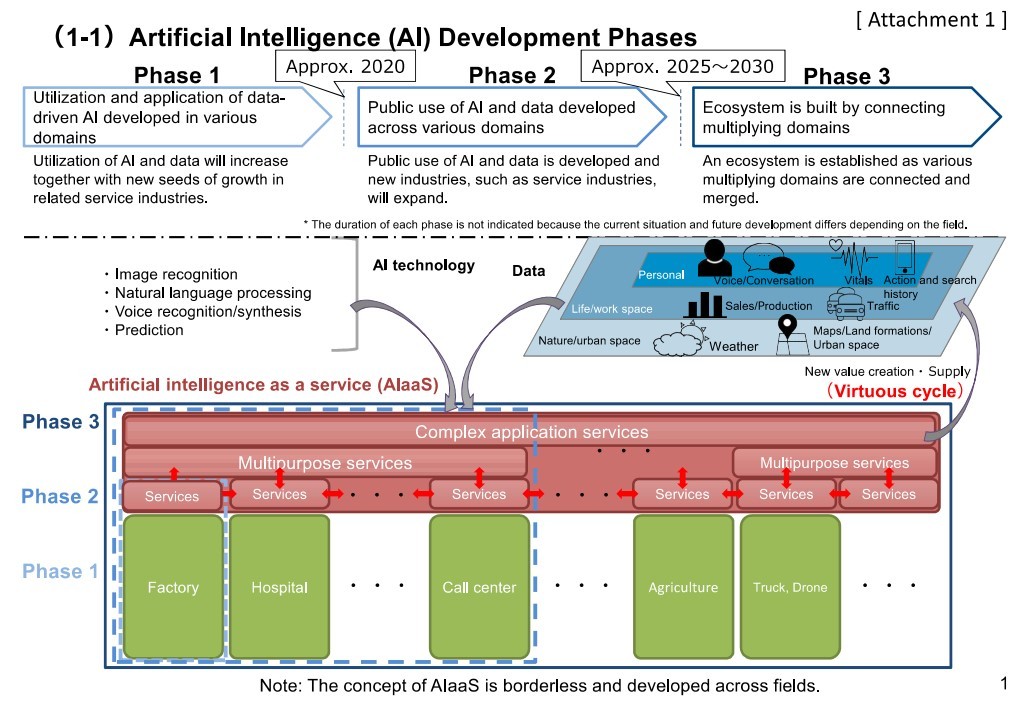

Japan’s national strategy is the most laconic (25 pages) and specific [17] and includes a basic description of the three stages in establishing a national AI as a service by 2030.

Three phases of establishing a national AI as a service in Japan by 2030

A set of roadmaps for the three priority areas (productivity; health, medical care and welfare; and mobility) is attached to the basic outline.

In addition, Japan has also developed a plan for integrating AI technologies with technologies in principal economic sectors in the three priority areas. The three phases of this integration demonstrate the level of planned technological progress and social changes.

The UK approach appears to be most detailed and elaborated, with the following documents being drafted:

— The 180-page “AI in the UK: Ready, Willing and Able?” report [18] published by the Authority of House of Lords in April 2018, which is largely based on the 77-page report “Growing the Artificial Intelligence Industry in the UK” [19] by Dame Wendy Hall, Professor of Computer Science at the University of Southampton, and Dr. Jerome Pesenti, CEO of BenevolentAI

— Two volumes of written and oral evidence by professionals and experts confirming the contents of the report (Volume 1 contains 223 pieces of written evidence on 1581 pages [20]; Volume 2 contains 57 pieces of oral evidence obtained at 22 sessions and set forth on 423 pages [21])

— A 40-page Government response to House of Lords Artificial Intelligence Select Committee’s Report on AI in the UK [22] presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy by Command of Her Majesty

What are the common features of the 20-plus national visions of the future AI, visions that are already set forth by states in a variety of forms, from plans and roadmaps (Japan) to “court rulings” giving specific commands to the national government (the United Kingdom)?

Having carefully studied the entire set of documents published as of end of August 2018, the author has distinguished two key trends that are clearly manifested in all “national strategies”:

1. Setting a course for AI nationalism

2. Setting a course for AI nationalization

Now we need to explain what these trends mean.

AI Nationalism

The First Source of AI nationalism: Ultra-High Expectations

The term AI nationalism became popular immediately after Ian Hogarth published an essay of the same title [23]. The essay defines AI nationalism as a new kind of geopolitics driven by continued rapid progress in machine learning in developed countries.

AI generates a new kind of instability on national and international levels, forcing the governments of developed countries to act so as not to find themselves among the losers in the new competition for AI superiority.

This competition is unique and unlike anything in the past, including the race for the nuclear bomb and intercontinental ballistic missiles.

AI is unique due to three factors, one economic and two military:

1. AI tools are universal as a means for increasing efficiency in virtually all post-industrial sectors and activities (the closest example of such universality is introducing electricity everywhere).

2. Based on prior military experience, AI’s is assumed to have tremendous potential for revolutionary breakthroughs

— both in developing radically new classes of comprehensive military technological solutions (such as stealth technologies),

— and in building radically more advanced AI-based military intelligence and managing military logistics and combat throughout the theatre of operations (including the change of customary paradigms for specific branches of the Armed Forces, as happened with air carriers transformed from a transport for intelligence aircraft equipped with deck guns into a floating airfield that is super-efficient in handling independent military tasks).

3. The assumed capability (not yet proven, but taken seriously by many military officials) of resolving the nuclear containment problem favouring a particular side (following the old cowboy wisdom of outdrawing your enemy).

These factors are largely hypothetical. They do not reflect real capabilities of the current AI technologies, but are rather extrapolations into the near future, provided that AI technologies continue to develop at the current pace.

In other words, all three factors that transform AI into a hypothetical means of gaining superiority in the international arena are merely expectations of the military and politicians.

But that does not prevent them from claiming that the world is on the threshold of a new singularity — namely, a military singularity. The Center for a New American Security (CNAS) report “Battlefield Singularity” [24] demonstrates how seriously the United States and China, leaders in the AI race, treat this matter. What is striking about this report is not only its logic and analytics, but the gigantic list of 334 U.S. and Chinese sources it cites.

The Second Source of AI Nationalism: Technological Entanglement

The unprecedented importance of AI can make the policies in this area the key element of government policy. However, a very unpleasant problem of technological entanglement, unique to AI technologies (for more on this, see [25]), gets in the way.

Technological entanglement means that globalization drives intertwining the interests and resources of international companies in developing dual-use technologies (peaceful and military). This intertwining is emerging and strengthening as a tight-knit and multi-faceted phenomenon.

Technological entanglement results in technological sovereignty virtually disappearing. Even the United States, the undisputed technological leader in AI, finds itself in a very difficult situation due to technological entanglement.

How can the United States retain its leading positions in AI and prevent their technologies from leaking to foreign rivals if:

— private business is the technological engine of the country;

— under globalization, international private giants, such as Alphabet, site their AI research labs in their chief rival (China) and hire thousands of professionals from that country;

— Chinese investors, including China’s largest AI companies, own significant shares in many promising AI companies in Silicon Valley; and

— thousands of Chinese students and graduate students study in the best United States universities?

The latest and most decisive turn in technological entanglement was China announcing its National Strategy for Military-Civil Fusion (for more on this, see [26]).

President of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation Robert Atkinson summarized the situation that resulted from technological entanglement in his article published in National Review on July 26, 2018.

— China has deployed a vast panoply of “innovation mercantilist” practices that seek to unfairly advantage Chinese producers, including:

o requiring foreign companies to transfer their technologies to Chinese firms in order to access the Chinese market;

o theft of foreign intellectual property;

o manipulation of technology standards;

o massive government subsidies; and

o government-backed acquisitions of foreign enterprises.

— The U.S. government should have one and only major trade-policy goal at this moment: rolling back China’s innovation-mercantilist agenda, which threatens the United States’ national and economic security.

The AI is expected to bring incredible returns ensuring a country’s superiority on the international arena. This and the exacerbating technological entanglement were the principal sources of technological and nationalist agenda of several countries, and their number is growing.

The potential consequences of this include: various protectionist measures by states in order to support “national AI champions”; restrictions (and the possible prohibition) on transferring patents, open research publications, and exporting AI technologies; and also restrictions (and the possible prohibition) on M&A transactions, the free overflow of investment and, of course, talent both in training and in professional activities.

Remote Weapons Come of Age

The Avant-Garde of AI Nationalism

As of the end of August 2018, China, the United States, India, the United Kingdom and France announced their intention to pursue some form of AI nationalism. These five countries have also announced the development of AI-based national military programs.

— China: within the framework of the 13th Five-Year Plan, the “Artificial Intelligence 2.0” program of the Plan of Innovative Scientific and Technical Development of the 13th Five-Year Plan, and the Three-Year Action Plan for Promoting Development of Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Industry (2018–2020) — under the umbrella of the national Military-Civil Fusion strategy [26].

— The United States: within the framework of the National Security Strategy [8], the National Defense Strategy [9] and the Memorandum on the Establishment of the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC) of the Department of Defense (JAIC) [14].

— India: within the framework of the National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence drafted for the Government by the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog) [27] and the “AI Development Roadmap for Ensuring India’s Defense and Security” drafted by Tata Sons at the instruction of the Ministry of Defense.

— France: as part of (1) the sharp increase in the country’s spending on AI to develop future weapons systems as announced by France’s Minister of Armed Forces Florence Parly (USD 1.83 billion); (2) the Parliamentary “Villani Report” [28] stating that AI is now the central political principle of ensuring security, maintaining superiority over the country’s potential enemies, and supporting its stance towards its allies; (3) a roadmap of AI capabilities for weapons and its first stage, the Man-Machine Teaming (MMT) project.

— When to comes to AI, the United Kingdom hopes to become part of U.S. programs and, within the framework of this cooperation, opened an AI Lab in May 2018, the centre for AI applied research at the Defense Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) following the relevant decision of the Secretary of State for Defense of the United Kingdom.

All the countries mentioned declared the following three policies as their principal vectors in steering the course of AI nationalism.

1. A policy guaranteeing the preservation of economic and military AI first mover advantages, as these countries consider themselves, and not without reason, to be trailblazers in AI.

2. A policy of preventing others from copying AI technologies, primarily those that are easily reproduced by any country with a similar technological level.

3. A policy of weakening the stimuli for international trade that automatically result in the global spread of AI technologies.

What is particularly noted is the “readiness to act” using the entire arsenal of state regulation by rapidly and decisively developing new rules and preventing any attempts to undermine national technological AI sovereignty.

AI Nationalization

The fear of falling behind in the global race for AI superiority has spawned the trend of AI nationalism. However, things go beyond AI nationalism.

When it turned out that China’s Military-Civil Fusion policy allowed the country, in the course of just a few years, to effectively catch up with the United States, the previously undisputed global AI leader, it became clear that other countries have no other option but to go down the same path.

Instead of the separation of state and business that is customary for developed countries, now everyone talks of the advantages of AI nationalization, i.e. integrating the resources of public and private companies, aligning the pace of introducing AI innovations, and refocusing strategic objectives on the state gaining economic, geopolitical and military advantages in the international arena.

The AI nationalization agenda is divided into:

· the agenda of the leaders of the AI race,

· the agenda of the outsiders of the AI race.

The Leaders’ Agenda: The United States and China

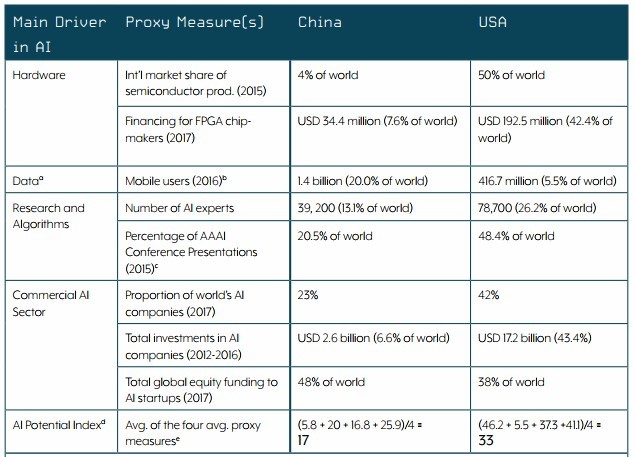

Some experts argue that China has barely covered half the ground of the United States in terms of AI [29].

Calculating the AI-potential index from the methodology in [29] demonstrates that China has covered just over half the ground of the United States in terms of AI.

However, a comprehensive analysis of China’s civil and military breakthrough technologies [30], the results of hearings in the United States–China Economic and Security Review Commission [31] and its final report to the U.S. Congress [32], as well as the latest report on the in-depth analysis of China’s weapons [33] recorded an approximate parity in the development of AI technologies in the United States and China.

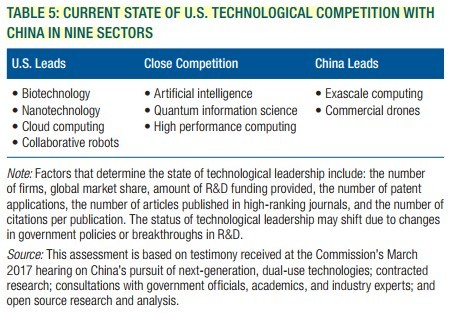

When examining the nine sectors of dual-use technologies that can be considered the most important in terms of breakthroughs, experts from the U.S. Congress classified AI as a group of three classes of technologies where the United States and China have approximate parity [31].

Unlike the high-quality, but civil report [29], these experts take three special factors into account in their conclusions [30–33]:

1. In China’s long-term development strategy, autonomous unmanned systems and AI will have the main development priority.

2. The specifics of China’s AI development roadmap, which prioritizes developing “intellectual (智能化) weapons,” including it on the list of four critical technological “strategic frontier” areas that set the objective of surpassing the U.S. military by using the “leapfrog development” (跨越发) strategy: a strategy of jumping over several development stages.

3. China’s intention to use AI to “accelerate the development of shashoujian (杀手锏) armaments,” which ironically, is translated into English as “Trump Card.”.

This is not a reference to President Trump, however, but rather to the so-called “shashoujian armaments.” The term “shashoujian” (杀手锏) can be translated differently: in English, it is a “trump card” or “assassin’s mace”; in Russian, it translates as “hitman.” The word refers to the Chinese legend where shashoujian was used to unexpectedly disable a stronger enemy by using a clever trick (something like the sling David used to defeat Goliath). In his time, Jiang Zemin, former General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, used the term “shashoujian” in the following manner: “Whatever the enemy fears most, that is what we should develop.” Since then, China has established the priority development of its “Trump Card,” the “shashoujian armament” that strikes at the enemy’s most vulnerable places. AI has proved very useful for such an approach.

Close Encounters of the Third Millennium

The United States Armed Forces is perfectly aware that China is banking on its “Trump Card.” Robert Work, U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense in 2014–2017, said that, “The whole ‘Chinese theory of victory’ is known (in translation) as ‘systems destruction warfare’ because it focuses on electronically paralyzing command-and-control rather than physically destroying tanks, ships, and planes.”

The simplest and most obvious example is using the swarm intelligence of micro drones to disable aircraft carriers.

Another example is the intellectualization of missiles. Here AI is set the objective of enabling “missiles to have advanced capabilities in sensing (感知), decision-making (决策), and execution (执行) of missions, including through gaining (认知) a degree of ‘cognition’ and the ability to learn” [34].

A high-ranking Pentagon official recently said that “the first nation to deploy an electromagnetic pulse weapon on the battlefield to disable enemy systems would reshape the face of warfare. Once again, it is far from obvious that is a race the United States will win.” He refers precisely to integrating the capabilities of electromagnetic pulse weapons and AI.

A detailed description of the entire landscape of potential threats stemming from China’s priority introduction of AI technologies into cutting edge weapons systems can be found in [35].

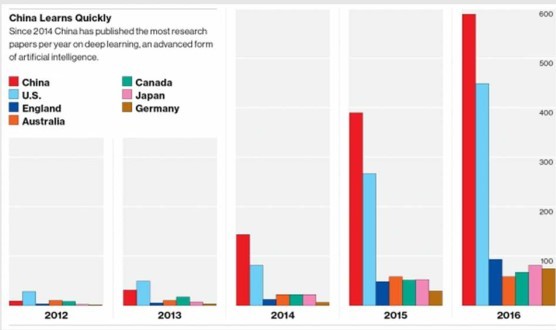

Thus far, the United States and China are head to head in AI. Many experts, however, believe that, in no more than ten years, China’s authoritarianism will summarily defeat U.S. democracy due to its absolute dominance in terms of the volume of data collected. China already has four times the volume of data that the United States posesses. And the gap is growing.

As Kai-Fu Lee, one of the most knowledgeable professionals in the U.S.–China AI confrontation and a former colleague of mine at Silicon Graphics, once said, “In fact, there is only one fundamental innovation in AI, and that is deep learning. Everything that is done now in AI is just fine-tuning deep learning to meet the needs of specific applied areas.”

Deep learning requires as much data as possible. And the one in possession of greater volume of big data has already most likely won the competition. Although, as Jack London’s Smoke Bellew said, “The race was not lost until one or the other won,” and the United States will not just give up in the AI arms race.

A duopoly looms in the near future. Thus far, the two global AI leaders, the United States and China, adhere to radically opposed strategies:

— China: continuing to do THAT regardless

— The United States: doing everything to hamper China in doing THAT

For a detailed description of THAT, see [36]. In short, it boils down to the following:

A. Using protectionist measures to protect its own market from import and competition in AI.

B. State-sponsored IP theft through physical theft, cyber-enabled espionage and theft, evasion of U.S. export control laws, and counterfeiting and piracy.

C. Coercive and intrusive regulatory gambits to force technology transfer from foreign companies, typically in exchange for limited access to the Chinese market.

D. Methods of information harvesting that include open source collection; placement of non-traditional information collectors at U.S. universities, national laboratories, and other centres of innovation; and talent recruitment of business, finance, science, and technology experts.

E. State-backed, technology-seeking Chinese investment.

The Agenda of the Outsiders in the AI Race

The real situation is such that everyone is the outsider in the AI race except for its leaders, the United States and China. Although technologically developed countries, such as France, Germany, India and South Korea appear to be incomparable to third-world countries in the level of AI technologies, the fate of becoming AI colonies of the leading countries awaits them all.

The absolute leadership of the United States in academic publications on deep learning. Source: Digital Transformation Monitor

In AI neo-colonialism, 21st century colonizers receive Big Data for their AI technologies, the new equivalent of gold and silver, while the only thing colonial countries can do is hope for the civilizational spirit of AI neo-colonialists and for their financial assistance.

However, in this situation, as in the race between the two leaders, “the race was not lost until one or the other won.”

For instance, European countries are trying to do at least something to avoid the fate of becoming colonies that supply the United States with big data.

Recognizing their loss to the United States and China in infrastructure and scale of their AI programs, European specialists describe their AI capabilities as “blobs of brilliance” and dream of ways to “take those blobs of brilliance and bring them all together.”

“A Special Outsider”: Russia’s Stance in the AI Race

The question of Russia’s potential and prospects is somewhat more complicated than simply filing it under the outsiders of the race.

First, there is a theoretical scenario where

outsiders could gain an advantage over the leaders in the field of AI for

military purposes. This scenario has remained outside the scope of our article,

since it does not aim to consider all possible scenarios, but only the most

probable ones. However, it is necessary to mention a scenario that favours

outsiders, since it is being considered and analysed by very influential

experts. This scenario was discussed in the Future

of War issue of Foreign Policy’s Fall

2018. Michael C. Horowitz’s article “The Algorithms of August” analyses the prospects of this scenario and sets

Russia apart as a “special outsider” that is, like China, potentially capable

of competing for leadership.

Second, the combination of Russia’s traditionally asymmetric responses to

geopolitical challenges, with its still considerable scientific and

technological Soviet legacy, can have major consequences at the junctions of AI technologies

and new classes of weapons (from hypersonic to electronic warfare). And there

is also the junction of AI with quantum computing and

some other things that might radically change the balance of military power in

the near future.

So nothing is clear-cut with Russia, and this fact should be studied separately, since the best works on the subject (for instance, “The Impact of Technological Factors on the Parameters of Threats to National and International Security, Military Conflicts, and Strategic Stability”) barely touch on these matters.

Where is AI Nationalization Taking Us?

However different the agendas of the leaders and outsiders of the AI race are, they presuppose the same steps essentially leading to Chinese-style AI nationalization.

First, it means establishing combined national civil military complexes for developing AI technologies.

Of course, the giants of AI business will resist this for all they are worth. For instance, on June 1, 2018, Google announced that it would not renew its contract to support a U.S. military initiative called Project Maven. This project is the military’s first operationally deployed “deep-learning” AI system used to classify images collected by military drones. The company’s decision to withdraw came after roughly 4000 of Google’s 85,000 employees signed a petition to ban Google from building “warfare technology.”

The response followed immediately.

As early as June 6, 2018, Gregory Allen, an expert of the Center for New American Security, published an article entitled “AI Researchers Should Help with Some Military Work.” The article formulates the new “ethical imperative” for commercial AI companies:

“The ethical choice for Google’s artificial-intelligence engineers is to engage in select national-security projects, not to shun them all.”

Allen writes about Google’s proposals to recuse themselves from participating in Project Maven:

“Such recusals create a great moral hazard. Incorporating advanced AI technology into the military is as inevitable as incorporating electricity once was, and this transition is fraught with ethical and technological risks. It will take input from talented AI researchers, including those at companies such as Google, to help the military to stay on the right side of ethical lines.”

The AI industry community rushed to the aid of Google, which had essentially been accused of its employees placing their ethical principles above national security. In July, Elon Musk, the founders of DeepMind, a founder of Skype and several renowned IT professionals called upon their colleagues to sign the pledge not to develop AI-based “lethal autonomous weapons,” aka “killer robots” (for more on this, see [37]).

In August, 116 renowned AI professionals and experts signed a petition calling upon the United Nations to prohibit lethal autonomous weapons. In their statement, the group states that developing such technologies will result in a “third revolution in warfare” equal to the invention of gunpowder and nuclear weapons.

While the United Nations remains silent, Sandro Gaycken, Senior Advisor to NATO, offered his response, noting that such initiatives are supremely complacent and risk granting authoritarian states an asymmetric advantage.

“These naive hippy developers from Silicon Valley don’t understand — the CIA should force them,” Gaycken said.

“Forcing to understand” applies not only to the giants of the AI industry, such as Google, but to a host of promising startups working on the cutting edge of AI development.

“Startups have to be embedded into large corporate structures, to have access to the kind of data they require, to build high-quality AI,” Gaycken believes.

The same logic applies to individual AI professionals: they should also work on national security tasks.

“There are also clear differences in how talent can be utilised in more authoritarian systems. The command and control economies of authoritarian countries can compel citizens, experts and scientists to work for the military. ‘Where you require very good brains to understand what is going on and to find your niche, to find specific weaknesses and build specific strengths — in those countries they simply force the good guys to work for them,’” Gaycken explains.

Such a picture is hard to imagine in the United States:

— AI startups working for giant AI corporations;

— Giant AI corporations working for the military;

— AI professionals working where the military tell them to (like “sharashkas” or R&D labs in the Soviet labour camp system under Stalin).

But that was the case of the USSR. And this is now the case of China…

Whether the United States will succeed in introducing such practices ultimately depends only on the level of threat. Any democracy ends where a high level of danger for national security begins.

Many influential people in the United States are convinced even now that the AI war with China is already on. The only thing remaining is to convince the majority of Americans of the same. After the election of Trump, it does not seem all that impossible.

References.

1. “Artificial Intelligence and National Security” drafted by Congressional Research Service experts for U.S. Congress in April 2018.

2. “Strategic Competition in an Era of Artificial Intelligence” and “Artificial Intelligence and International Security” reports published by the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) in July 2018.

3. “Artificial Intelligence and National Security” reports drafted by the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs for the U.S. Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) in July 2017.

4. “Summary of the 2018 White House Summit on Artificial Intelligence for American Industry” report drafted by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy in May 2018.

5. “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Innovation” report drafted by experts of the National Bureau of Economic Research in September 2017.

6. “The Manhattan Project, the Apollo Program, and Federal Energy Technology R&D Programs: A Comparative Analysis” report drafted by experts of the Congressional Research Service for U.S. Congress in June 2009.

7. “FY2019 Budget Request Administration R&D Priorities”

8. “National Security Strategy of the United States of America”

9. “Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of The United States of America”

10. “Govini’s DoD Artificial Intelligence, Big Data and Cloud Taxonomy”

11. “The Networking and Information Technology Research and Development Program”

12. “The National Artificial Intelligence Research and Development Strategic Plan”

13. “Defense Innovation Board Recommendations”

14. “Memorandum: Establishment of the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC)”

15. “Memorandum: FY 2020 Administration Research and Development Budget Priorities”

16. “An Overview of National AI Strategies” report drafted by Politics + AI

17. “Artificial Intelligence Technology Strategy” report and accompanying presentation drafted by the Strategic Council for AI Technology of Japan in May and October 2017.

18. “AI in the UK: Ready, Willing and Able?” report drafted by the Select Committee on Artificial Intelligence of the United Kingdom in April 2018.

19. “Growing the Artificial Intelligence Industry in the UK”

20. “COLLATED WRITTEN EVIDENCE VOLUME” report drafted by the Select Committee on Artificial Intelligence of the United Kingdom in April 2018.

21. “COLLATED ORAL EVIDENCE VOLUME” report drafted by the Select Committee on Artificial Intelligence of the United Kingdom in April 2018.

22. “Government Response to House of Lords Artificial Intelligence Select Committee’s Report on AI in the UK: Ready, Willing and Able?” report drafted by the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy by Command of Her Majesty and submitted to the Parliament of the United Kingdom in June 2018.

23. “AI Nationalism,” Jan Hogarth, essay published in June 2018.

24. “Battlefield Singularity. Artificial Intelligence, Military Revolution and China’s Future Military Power” published by the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) in November 2017.

25. “Technological Entanglement. Cooperation, Competition and the Dual-Use Dilemma in Artificial Intelligence” report published by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in June 2018.

26. “Blurred Lines: Military-Civil Fusion and the ‘Going Out’ of China’s Defense Industry”

27. “National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence“” report drafted by the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog) for the Government of India in June 2018.

28. “FOR A MEANINGFUL ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE” report drafted by the French Parliamentary Commission under the leadership of Cédric Villani on the instructions of the Prime Minister of France.

29. “Deciphering China’s AI Dream. The Context, Components, Capabilities, and Consequences of China’s Strategy to Lead the World in AI” report published by the Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford in March 2018.

30. “Planning for Innovation: Understanding China’s Plans for Technological, Energy, Industrial, and Defense Development” report drafted by the US–China Economic and Security Review Commission in July 2016.

31. “CHINA’S ADVANCED WEAPONS. HEARING BEFORE THE U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION”

32. “2017 Report to Congress of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission” Executive Summary and Recommendations of the report and its full text

33. “China’s Advanced Weapons Systems” drafted by Jane’s by IHS Markit for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission in May 2018.

34. “Chinese Advances in Unmanned Systems and the Military Applications of Artificial Intelligence—the PLA’s Trajectory towards Unmanned, “Intelligentized” Warfare” — Testimony before the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission in July 2017.

35. “Implications of China’s Military Modernization” — Testimony before the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission in February 2018.

36. “How China’s Economic Aggression Threatens the Technologies and Intellectual Property of the United States and the World” report published by the White House Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy in June 2018.

37. “Initial Reference Architecture of an Intelligent Autonomous Agent for Cyber Defense,” ARL US Army Research Laboratory, March 2018.

(votes: 7, rating: 4.86) |

(7 votes) |

How can we teach the AI the right values?

The Ethical and Legal Issues of Artificial IntelligenceSystems that use artificial intelligence technologies are becoming increasingly autonomous in terms of the complexity of the tasks they can perform, their potential impact on the world and the diminishing ability of humans to understand, predict and control their functioning. Most people underestimate the real level of automation of these systems, which have the ability to learn from their own experience and perform actions beyond the scope of those intended by their creators. This causes a number of ethical and legal difficulties.

China Missed the Industrial Revolution, But It Won’t Miss the Digital OneThe country's leadership is trying to heed the lessons of the past so as not to miss the historic chance of leading the digital revolution

A Brave New World without WorkAs Strong Artificial Intelligence continues to develop, so does the range of jobs it can do

Close Encounters of the Third MillenniumThe Arms Race in Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems has already Begun