The Obsolete Legacy of Antarctica

(votes: 2, rating: 5) |

(2 votes) |

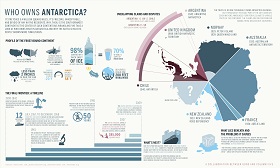

The Antarctic has long been of marginal importance for Russia, although Antarctic issues are closely linked to higher-profile ones involving the Arctic. Moscow is adamant about preserving the revised system for sectoral division of the Arctic and maintaining its exclusive rights to the Northern Sea Route, while also rejecting the mechanical application of the principles of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea to the Arctic Ocean. At the same time, Russia supports the Antarctic’s international status, the Southern Ocean as a neutral zone, and a ban on economic activity on the southernmost continent. As a result, diverging approaches to both the Arctic and Antarctic complicate Russian diplomacy.

The military conflict in Ukraine has overshadowed all other foreign policy problems for Russian audiences for some time. However, Moscow may soon face trouble in the Arctic, as it is going to file its improved claim for about 1.2 million square kilometers of the Arctic shelf with the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. Approval is not clear-cut, given opposition from the United States, Canada and possibly Norway. As a result, Russia might well have to unilaterally declare its sovereignty over the Soviet sector of the Arctic.

This is lending new facets to existing Antarctic issues. The continent has long been of marginal importance for Russia, although Antarctic issues are closely linked to higher-profile ones involving the Arctic. Moscow is adamant about preserving the revised system for sectoral division of the Arctic and maintaining its exclusive rights to the Northern Sea Route (NSR), while also rejecting the mechanical application of the principles of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea to the Arctic Ocean. At the same time, Russia supports the Antarctic’s international status, the Southern Ocean as a neutral zone, and a ban on economic activity on the southernmost continent [1]. As a result, diverging approaches to both the Arctic and Antarctic complicate Russian diplomacy.

In the 1920s, five Arctic states split the Arctic into sectors and so became the five Arctic powers, with the Antarctic situation seemingly developing along the same lines.

Arctic Failure

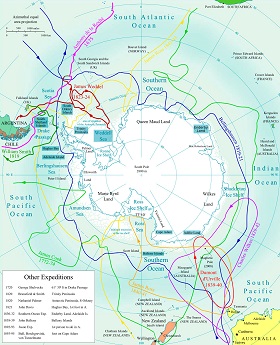

In the 1920s, five Arctic states (Canada, the Soviet Union, Norway, Denmark and the United States) split the Arctic into sectors and so became the five Arctic powers, with the Antarctic situation seemingly developing along the same lines [2].

Claims for the Antarctic ran as follows:

- Great Britain that in 1908 declared the establishment of the British Antarctic Territory between longitudes 20°W and 80°W [3].

- New Zealand that in 1923 announced its sovereignty over Ross Dependency, lying between 150°W and 160°E, and King Edward VII Land, between latitude 77°S and longitude 155°W.

- Australia that in 1933 claimed Victoria Land, located between longitudes 44°E and 136°E, and Enderby Land, between longitudes 142°E and 160°E.

- France that in 1924 declared the establishment of Adelie Land between longitudes 136°E and 42°E, and in 1955 also set up a special administrative entity – the French Southern and Antarctic Territories.

- Germany that in 1939 declared the creation of New Swabia between longitudes 10°W and 20°E.

- Norway that in 1927-1929 proclaimed sovereignty over Peter I island, Bouvet Island and adjacent territories (Bouvet Sector), and in 1939 – over Queen Maud Land between longitudes 20°W and 44°E.

- Chile that in 1940 announced the establishment of Chilean Antarctica between longitude 53° and 90°W.

- Argentina that in 1943 proclaimed Argentinean Antarctica between longitudes 25°W and 74°W.

In 1939, the United States set up its Antarctic Service, which in 1939-1941 surveyed Edward VII Land, despite protests from Great Britain and New Zealand. In 1946-1948, the U.S. Antarctic Service held military expeditions High Jump and Windmill, and in 1955 carried out one more – Deep Freeze – jointly with New Zealand – indicating that former British dominions preferred to explore the Antarctic with Washington rather than with London.

Until the mid-20th century, the USSR’s Antarctic policy had lacked any overarching strategy. In 1939, Moscow joined Washington in lodging a protest against Norway because of its claim on the Bouvet Sector. The Soviet geographical maps of the 1930s-1950s showed the self-proclaimed Antarctic dominions in dotted lines. In the absence of any clear Soviet interests, Joseph Stalin seemed ready to recognize the division of the Antarctic along similar lines to the approach taken on other continents.

The Soviet Antarctic expedition of 1956 sparked American fears that Moscow might expand its influence in the Southern Hemisphere. After a series of negotiations, the two countries reached a compromise that the continent remains neutral. The Antarctic Treaty of December 1, 1959 prohibited the declaration of state sovereignty over any part of Antarctic territory, and also any kind of military activity, including nuclear tests and the disposal of nuclear waste in the area. Economic activities, such as mining, were also banned. The Antarctic was open only for scientific research. On June 23, 1961, the Treaty came into force.

Parallel with the Antarctic Treaty, the USSR and the United States agreed to declare the Antarctic seas neutral. Back in 1937, the International Hydrographic Organization delineated the Southern Ocean as limited by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current flowing between latitudes 40°S and 50°S. In 1953, the IHO confirmed the existence of the new ocean, but did not insist on any obligatory division of the World Ocean into five oceanic spaces.

The Struggle Continues

Prohibited the declaration of state sovereignty over any part of Antarctic territory, and also any kind of military activity, including nuclear tests and the disposal of nuclear waste in the area.

However, the quest for the Antarctic continued. The claimants even used philately to these ends, by issuing stamps showing their ‘Antarctic territories’. In 2004, Australia filed a claim for the Antarctic shelf adjacent to "the Australian Antarctic sector" to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. Similar claims may well come from Great Britain, Argentina, New Zealand and South Africa.

At the same time, the failed Antarctic powers became embroiled in a tussle for territories between latitudes 40°S and 60°S [4], i.e. the territories around Antarctica. The contest for these islands [5] and their continental shelf gave rise to the problem of the Southern Ocean limits – whether it should be the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (latitude 40°S) or the Antarctic Treaty area (latitude 60°S) [6]. This controversy peaked in 1982, with the war between Great Britain and Argentina for the Falkland Islands, which the British often refer to as the Antarctic war. The conflict provided a precedent of military engagement for the revision of the legal status of the lands around the Antarctic. The incident also placed a question mark over the Antarctic’s nuclear-free status, as in 2003 London hinted that its ships may have carried nuclear weapons during the Falkland War. UK air force deployment on the American military base on Ascension Island in the heart of the Atlantic Ocean also raised the question of military operations in the Antarctic involving the use of lands beyond its borders. For example, in 1986, Brazil declared its zone of interests in the Antarctic between longitudes 28°W and 53°W.

Moscow and Washington took action to strengthen Antarctica’s international status by signing the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources in 1980, hoping that this would bolster its status of an international nature reserve. In 1986, Antarctica was declared a nuclear-free zone [7]. In 1988, the Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities was proposed for signing, and in 1991 the Madrid Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic was signed, becoming effective in 1999 and substantiating the provisions of the 1959 Treaty by imposing a 50-year moratorium on mineral exploration and mining in Antarctica.

The claimants even used philately to these ends, by issuing stamps showing their ‘Antarctic territories’.

In 2000, the IHO proclaimed the obligatory division of the world into five oceans, confirming the status of the Southern Ocean as a separate body of water below latitude 60°S. However, Britain, Chile and Argentina insisted on a latitude south of Cape Horn, i.e. the border of the Antarctic drifting ice and surface waters [8].

Russia's Stand

Antarctic claims — Australian stamp

The failed Antarctic powers became embroiled in a tussle for territories between latitudes 40°S and 60°S, i.e. the territories around Antarctica. The contest for these islands and their continental shelf gave rise to the problem of the Southern Ocean limits.

The Russian Federation employs a two-pronged tactic. Moscow has taken official steps to strengthen the system of Antarctic co-governance. In 2001, Russia used U.S. support to establish the Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty headquartered in Buenos Aires, while in 2003 Madrid became the venue for the signing of a package of documents on its operations, and it launched on September 1, 2004.

On February 17, 2004, the Russian Foreign Ministry issued advisory note titled Antarctica, stressing that Russia opposes recognition of territorial claims in the Antarctic and supports the system of its international governance. On December 25, 2009, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov made a special statement on Russia's intention to strictly observe the Antarctic Treaty, specifying that Moscow has no territorial claims toward that continent.

However, a Russian Foreign Ministry note dated February 17, 2004 said that according to the 1959 Treaty Russia reserves its rights to lands discovered in 1820-1822 by expeditions led by Fabian von Bellinghausen and Mikhail Lazarev. The Antarctic also became an issue for discussions between Russian and Latin American leaders, with cooperation discussed as a real possibility during the visits of Chilean President Michele Bachelet to Moscow on April 3-4, 2009 and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev to Argentina on April 14-15, 2010.

Since 2010, Russia has not been active on the Antarctic track, and on September 8, 2012 it signed the Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in the Antarctic with the United States to signify its partial refusal to consult on the Antarctic with the Latin American states. Meanwhile, the Antarctic may serve for Moscow for a tradeoff during any discussion on division of the Arctic.

Trading off

Antarctic claims — British stamp

In the current global environment, an internationalized Antarctica and Southern Ocean would play into U.S. hands. Naval bases akin to those of the British Empire may, theoretically, be deployed only in Antarctic waters. And the United States has all preconditions to have a firm footing there, as the Southern Hemisphere is dominated by the navies of the United States, Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand. The only way to hypothetically upend this hegemonic stability seems to lie in resuming the struggle to divide the Southern Ocean and Antarctica.

There are scant obvious dividends for Russia from the internationalization of the Antarctic. The only gain seems to be unobstructed scientific activity on the basis of bilateral agreements with friendly countries. At the same time, a change in position on Antarctica would immediately offer Russia a range of openings.

First, the United States would lose all grounds for accusing Russia of being inconsistent in its Arctic and Antarctic policies, as Moscow would steadfastly work to divide the circumpolar spaces into sectors.

In the current global environment, an internationalized Antarctica and Southern Ocean.

Second, Washington would not be able to use the Antarctic precedent for the internationalization of the Arctic Ocean, while Russia would not have to prove the difference between the Arctic and Southern oceans [9].

Third, it would be easier for Russia to defend the exclusive rights to the NSR and its inland seas in the Arctic. The historical domains of the Antarctic powers, which the USSR was about to recognize in the 1940s, may serve as a workable precedent for the Arctic.

There are scant obvious dividends for Russia from the internationalization of the Antarctic.

Fourth, Russia could win more allies for resolving Arctic issues, primarily the Latin American states of Chile, Brazil, and Argentina. Consultations with New Zealand also appear likely, given the broadly positive nature of the bilateral relationship (regrettably, the opposite is the case with Australia). In the long view, Russia might even enter into talks with Great Britain and France, which still lay claim to Antarctic territories. In return, Moscow could request assistance from Paris and London in advancing its Arctic interests.

Russia might even enter into talks with Great Britain and France, which still lay claim to Antarctic territories.

Fifth, Russia's new approach would bolster its positions in Latin America, which is interested in Antarctica not just for historical reasons or geopolitical prestige but also for economic reasons, i.e. fishing in the Southern Ocean. The division of Antarctica may open up new opportunities for Russian-French and even Russian-British dialogue.

A Roadmap for Antarctica

In order to achieve this result, Russia does not need to withdraw from 1959 Antarctic Treaty, which would be an excessively painful and unproductive turn of events. However, Moscow could launch consultations with potential Antarctic powers on recognition of their special rights within Antarctica’s territories. The Brazilian precedent of 1986, when the country declared the presence of its zone of interests in the Antarctic without seeking any formal attachment of the relevant territory, seems the most helpful precedent here. Also of interest is the French initiative of early 2010 about creating Antarctic reserves in the relevant countries’ trusteeship. If France sets up such a reserve in Adelie Land and New Zealand – in King Edward VII Land, it would indirectly mean recognition of their claims to these Antarctic territories.

Additionally Russia may request a revision of the 1991 Madrid Protocol that blocks economic activities in Antarctica. An alternative could be a quota system for the use of Antarctic biological resources for certain states, and Russia would automatically gain some points among the states involved.

Russia should not do this as a goodwill gesture but only if the Antarctic states do something in return, such as:

- Issuing a statement on supporting Russia in the Arctic dialogue.

- Recognizing Russia’s rights toward the Soviet Arctic sector.

- Issuing a joint statement on the mutual recognition of historical claims of the parties in the Arctic and the Antarctic.

It would be best not to put these initiatives on the backburner, but rather to launch the discussion before the Russian Arctic claim has been filed with the UN Commission on the Limits of Continental Shelf.

***

Russia is currently in a difficult position regarding its stance on the Arctic, since all other Arctic states – the United States, Canada, Denmark and Norway – belong to NATO and would not like to see a stronger Russia. Sweden and Finland, the two sub-Arctic countries that hold historical grudges against Russia, support the United States in its desire to internationalize the Arctic Ocean. However, any search for allies on the Arctic would require changes in Russia's approach to Antarctica, whose current neutral status is the obsolete legacy of the 1950s and requires revision for the sake of Russia's greater, strategic interests.

1. V.Korzun was one of the first experts to analyze this problem. See, for example: Korzun V. Russia in the World Ocean: New Geopolitical Conditions, 2003.

2. Dodds K. Geopolitics in Antarctica: Views from the Southern Oceanic Rim. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, 1997.

3. The British Antarctic territory (BAT) used to include a part of the Antarctic’s territory (Graham land), South Orkney Islands, South Shetland Islands, South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands. Until 1963 the BAT was divided into three territorial districts and was administrated by the British governor of the Falkland Islands (archipelago in the south-west part of the Atlantic ocean).

4. Tomczak M., Godfrey J.S. Regional Oceanography: An Introduction. N.Y.: Pergamon, 1994.

5. Claims have been made by Argentina and the United Kingdom (the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands) as well as Argentina and Chile (islands of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago). Norway, despite the protests of the Soviet Union and the United States, upheld the royal decree of 1927 on the accession of the “Bouvet sector.” France’s Antarctic dominions include the Crozet Islands, Kerguelen Island, the island of Saint-Paul and Amsterdam Islands. Australia controls Heard and McDonald Islands as well as Macquarie Island, New Zealand controls Auckland and Campbell Islands, and South Africa controls Prince Edward Island. The UK regards its Antarctic territories as the island of Tristan da Cunha and the island of Goff, which are located north of 60° southern latitude.

6. Pyne S.J. The Ice: A Journey to Antarctica. Washington: University of Washington Press, 1986.

7. The Antarctic Treaty of 1959 included a demilitarized zone in which nuclear weapons testing was prohibited. However, an official announcement about this nuclear-free zone was only made on December 11, 1986, the date on which the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty took effect.

8. Keegan J., Wheatcroft A. Zones of Conflict: An Atlas of Future Wars. N.Y.: Simon & Schuster, 1986.

9. In October 2007, the Wilton Park Conference, a popular informal meeting organized by the British Foreign Office with the support of the U.S. State Department, addressed the issue of drafting an international treaty on the Arctic as a kind of analogue to the Antarctic Treaty of 1959.

(votes: 2, rating: 5) |

(2 votes) |