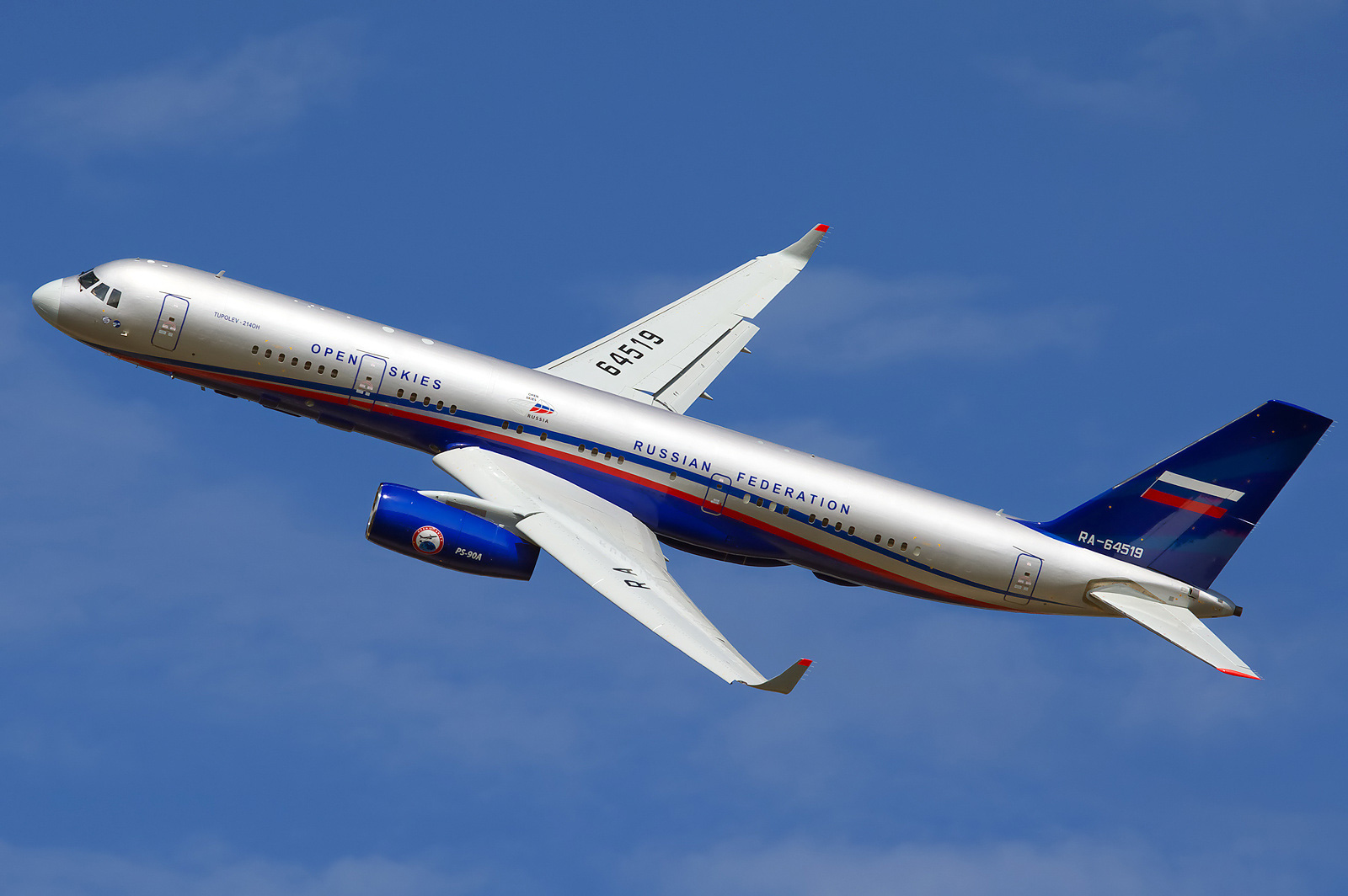

Recent years have proved very difficult for arms control, affecting a wide range of areas: the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty), a fundamental element of strategic stability, collapsed; the Treaty on Open Skies is in jeopardy; the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, or the Iran deal) is in its death throes; the 2015 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) failed, and there is no guarantee that the 2020 conference will be a success. If the anniversary event (in 2020, the NPT celebrates its 50th year) fails, it will deal a significant blow to the Treaty. It is possible that the Iranian and Korean problems, the confrontation between nuclear powers and the proponents of the “post-modern NPT,” i.e. the populist Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), and the degradation of arms control along the U.S.–Russia axis will cause the NPT to collapse.

The destructive stance of the United States concerning the preservation of those treaties is the common element that unites all the agreements that are cracking at the seams in various areas. Naturally, placing the blame on the United States may look like another ideologically motivated charge against the “Anglo-Saxons,” accusing them of committing all the deadly sins. Yet, it is not anti-American in the least to state that the United States is, of its own free will, withdrawing from numerous treaties. Moreover, in saying that, we will sound the same chord as the American authorities and Donald Trump himself, who had proclaimed withdrawing from “bad deals” as one of the mottos of his presidency. And bad deals are those that were not concluded by Trump himself. In his very first telephone conversation with Vladimir Putin, the President of the United States categorized New START as one such “bad deal,” blankly stating that it was “one of several bad deals negotiated by the Obama administration,” one that “favours Russia.”

In June 2019, RIAC published the article “End of Nuclear Arms Control: Do Not Beware the Ides of March” calling upon readers to look to a future in which New START was no more without immediately becoming utterly depressed. And now I would like to reiterate that Russia could try to put the short hiatus to good use, for instance, by completing the rearmament of its strategic nuclear forces (without being so open in demonstrating the new weapons) and approaching the new treaty with a readiness to write off the old missiles. Today, Russia’s image benefits from the country’s desire to extend a treaty that is important for the entire world, and from the bold steps it has taken to meet its partners halfway. One example of the latter is the demonstration of the Avangard UR-100UTTKh ICBMs refitted with gliders, something that it did not technically have to do had it manipulated the definitions of the technology. Even though Russia is accused of all deadly sins, the current transparency mechanisms do not make it possible to levy clear charges of non-compliance with New START and to give media support to the Treaty’s opponents.

However, the long hiatus in nuclear arsenal control, the prospect of a prolonged arms race that will inevitably involve China (which has limited itself so far as, clearly, the country could have had far larger strategic nuclear forces, but has thus far preferred, instead of trying to catch up with the United States and Russia in terms of the size of its arsenal, to wait for them to reduce their own arsenals so that they are closer to that of China), and the general degradation of the global non-proliferation regime are all major dangers.

This period may begin in a year. Perhaps 365 days does not look quite as ominous as the Doomsday Clock that the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists set at 100 seconds to midnight, but 365 days is far more inexorable, and all of us becoming vegans will hardly help here.

One year from now, on February 5, 2021, the Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms, better known as New START, will expire. With each passing month, hopes for its prolongation become slimmer.

Recent years have proved very difficult for arms control, affecting a wide range of areas: the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty), a fundamental element of strategic stability, collapsed; the Treaty on Open Skies is in jeopardy; the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, or the Iran deal) is in its death throes; the 2015 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) failed [1], and there is no guarantee that the 2020 conference will be a success. If the anniversary event (in 2020, the NPT celebrates its 50th year) fails, it will deal a significant blow to the Treaty. It is possible that the Iranian and Korean problems, the confrontation between nuclear powers and the proponents of the “post-modern NPT,” i.e. the populist Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), and the degradation of arms control along the U.S.–Russia axis will cause the NPT to collapse.

The destructive stance of the United States concerning the preservation of those treaties is the common element that unites all the agreements that are cracking at the seams in various areas. Naturally, placing the blame on the United States may look like another ideologically motivated charge against the “Anglo-Saxons,” accusing them of committing all the deadly sins. Yet, it is not anti-American in the least to state that the United States is, of its own free will, withdrawing from numerous treaties. Moreover, in saying that, we will sound the same chord as the American authorities and Donald Trump himself, who had proclaimed withdrawing from “bad deals” as one of the mottos of his presidency. And bad deals are those that were not concluded by Trump himself. In his very first telephone conversation with Vladimir Putin, the President of the United States categorized New START as one such “bad deal,” blankly stating that it was “one of several bad deals negotiated by the Obama administration,” one that “favours Russia.”

This approach applies to all areas equally: speaking at the annual meeting of the National Rifle Association (NRA), Trump decided he would delight those in attendance by announcing that the United States would be withdrawing from the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) because “we will never allow foreign bureaucrats to trample on your Second Amendment freedom.” The pathos is rather ironic, since the ATT has been consistently criticized precisely for lacking specific control measures, not to mention the fact that using the ATT to prohibit the sale of arms to Americans would only be possible if individual American citizens had been charged with genocide or if the UN Security Council imposed personal sanctions.

In late January 2020, the U.S. Administration, in its search for “bad deals,” turned its eagle eye to Barack Obama’s prohibition on the use of landmines [2] and lifted it. The pressing military urgency of this decision is fairly dubious, and it prompted predictable criticism from arms control proponents.

On the other hand, we should not think that the President of the United States does not know what he is doing or is acting out of constitutional dislike for the existing world order. It is just that his target audience and voter base are not experts in arms control or international law. Rather, they are regular people who frequently have no idea about the substance and practical purpose of specific treaties yet are indignant over any infringement upon the national prestige or, even worse, attempts to disarm their homeland.

It should also be acknowledged that measures similar to those undertaken by the United States would gain widespread approbation among the Russian public, which is also quite sensitive to official international commitments. Examples are easy to find. For example, among all the proposed constitutional amendments, the suggestion to enshrine the “primacy of Russian domestic law over international law” gained the widest approval. Patriotic circles traditionally consider the current primacy of international law an important and grave infringement. In fact, nothing would change in practice: international treaties affecting Russian legislation and, in general, all international treaties of even the smallest importance must be ratified by parliament, i.e. they must be voted for as a Russian law. The President of the Russian Federation, unlike his American counterpart, cannot even simply prolong New START without parliamentary approval.

The Patient is Stable, but the Prognosis Is Not Good

Unfortunately, we may never see the much-anticipated signing of the deal by the President of the United States (while the Russian authorities have repeatedly announced they are categorically in favour of prolonging the Treaty). Thus far, it does not look like Trump has any intention of damaging his rating in the election year by extending Obama’s “bad deal,” especially given the persistent anti-Russian agenda of the U.S. media. Additionally, Trump appears to sincerely believe that if he manages to stay in the White House for another term, he will be able to conclude a wonderful “big deal” that would ideally include China as well. Unfortunately, it is difficult to share his optimism, since even the traditional bilateral START-IV will be difficult to negotiate from scratch.

Compared to 2010, when New START was signed, an entire range of points became more complicated:

— The new deal must stipulate the continuation of arms reduction, otherwise it will be perceived as abandoning nuclear disarmament commitments. Even ten years ago, Russia viewed the caps of 1550 warheads and 700 delivery vehicles as minimally “comfortable” and thus allowing Russia to disregard the arsenals of U.S. allies in NATO (the United Kingdom and France have a total of up to 500 warheads at different levels of combat readiness). The United States cannot ignore China’s arsenal, even though an official and solid military alliance between Moscow and Beijing does not appear to be on the cards.

— START Treaties always “rested” on the INF Treaty as a constant, proceeding from the premise that ground-launched missiles with a range of 500–5500 kilometres did not exist. With the INF Treaty in tatters and the United States launching a series of intermediate-range weapons projects, the potential of delivering a counterforce strike against Russia’s strategic nuclear forces increases. From a purely geographical point of view, Russia cannot retaliate with a mirror strike: Russian missiles will be aimed at U.S. and NATO bases in Asia and Europe, but there are no U.S. strategic nuclear forces deployed there.

— The rapid development of hypersonic weapons in general. In addition to the abovementioned high-precision intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBD), which are hard to intercept and have manoeuvrable re-entry vehicles, the perspective air missiles (primarily Russia’s Kinzhal and the United States’ AGM-183A ARRW and HCSW) and sea-based missiles (mainly the United States’ IRCPS [3], which is currently in development) also increase the possibilities for a counterforce strike.

— The evolution of the U.S. global missile defence programme. At the request of the Russian military leadership, New START mentioned that further reductions would require negotiations on missile defence restrictions. Although currently the development of ICBM interceptors has been mostly abandoned as a dead-end concept, work is being done on deploying missile defence elements in outer space and developing new ground-based interceptors.

— The overall militarization of outer space.

— Given the reduced strategic nuclear arsenals, the role of tactical nuclear weapons (TNW) increases. Although there are no exact figures, it is generally believed that Russia has a far larger TNW arsenal than the United States and NATO. It is hard to imagine Moscow easily agreeing to unilateral reductions in this area, since it sees the TNW as a counterbalance to NATO’s numerical superiority.

— U.S. concerns about the possible development by Russia of delivery vehicles with strategic capabilities (Burevestnik, Poseidon) that do not fall within the definitions outlined in New START.

— The obvious exacerbation of U.S.–Russia and U.S.–China relations in general.

— The overall negative background in arms control.

The points listed above do not allow us to confidently state that, as an intermediary way out, the parties will hurriedly negotiate an analogue of the 2002 Treaty Between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Strategic Offensive Reductions (SORT, also known as the Treaty of Moscow), where, having run into contradictions in negotiating START-II, the parties agreed to prolong START-I with reduced limits that were not even expressed in exact figures (sic!) [4].

Although as of today, the above-stated problems do not undermine the balance of power (hypersonic weapons will take years to perfect, and it will be even longer before missile defence programmes are capable of deflecting a major strike, plus, exotic delivery vehicles are still far from being deployed), in the long term, even New START will become unacceptable.

Fight to the End

Obviously, to preserve strategic stability in the future, we will indeed need a wonderful “big deal." However, it probably will not be Trump’s deal since even its basic outlines are unlikely to have been agreed on by 2024. All in all, the new instruments of undermining this stability will not have materialized yet. However, it will be much easier to prepare the deal in the calm of a flawed but still functioning New START, even if it is becoming antiquated. What will we lose on February 6, 2021, if the United States does not try to meet Russia halfway?

— Effective transparency methods: inspections, exchanging telemetric data and detailed information on the composition of strategic nuclear forces; non-interference in the operation of satellite reconnaissance equipment; consultative committees. Taken together, these things did not instil “confidence,” that is too loaded a word, but they did provide the particular comfort of knowing your opponent. And it is precisely the lack of understanding that resulted in dangerous exacerbations of the Cold War, such as the bomber/missile gap [5], the Suez [6] and Caribbean crises and Able Archer 83 [7].

— The capability of the leading nuclear states to serve as examples in arms control. Arms control is coming apart at the seams as it is, and the fact that the world’s two leading arsenals are shaking off all restrictions while at the same time hurling accusations at each other threatens to rip it apart altogether. In the nuclear area, the TPNW “nihilists” will have far weightier arguments against the NPT, accusing the five legal nuclear powers of being hypocritical when they assure others of their commitment to the Treaty’s fundamental article (Article VI), which states that “each of the Parties to the Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and nuclear disarmament.” However, should the Parties begin to withdraw from the NPT, clearly not all of them will transition to the TPNW. Neither the United States nor Russia need more nuclear powers.

— Grounds for further talks. It is one thing to transfer working provisions to a new treaty. Still, it is an entirely different matter to give the opponents of a particular definition or mechanism that had been agreed upon after much effort an excuse to start debating it from scratch.

— Opportunities for Russia to spend the larger share of its defence budget on conventional forces. Entering an “inter-treaty” stage will inevitably boost the standing of those who support spending money on strategic nuclear forces, and the limited funds will be taken from the Armed Forces, the Aerospace Forces and the Navy. As a result, the military will be short of equipment that could be used in actual conflicts in the coming decades, and it will be done to procure and subsequently eliminate additional “containment” means which in and of themselves are undoubtedly important and necessary. Yet, when their numbers are surplus to requirements, it does not improve the country’s security.

It would appear that we have failed to mention the primary loss, and that is the quantitative ceilings on weapons. This is no coincidence, as we are unlikely to lose them, since the parties will be careful to maintain their image on the global stage and thus declare that they have no intention of exceeding these ceilings (or at least will not be the first to do so, and here we return to the issue of transparency). The United States does not currently mass-produce strategic delivery vehicles, while refitting the existing missiles with additional warheads is a visible, aggressive and slow step (for instance, refitting all 400 Minuteman III ICBMs with three warheads instead of just one will take over three years).

Russia could also go a little over the limit by refitting its missiles, but as regards a more crucial parameter—the number of strategic delivery vehicles—New START’s pool reserve [8] is such that 10 Borei-class submarines and three divisions of Yars mobile ICBMs would have to be commissioned simultaneously to reach the limit.

In June 2019, RIAC published the article “End of Nuclear Arms Control: Do Not Beware the Ides of March” calling upon readers to look to a future in which New START was no more without immediately becoming utterly depressed. And now I would like to reiterate that Russia could try to put the short hiatus to good use, for instance, by completing the rearmament of its strategic nuclear forces (without being so open in demonstrating the new weapons) and approaching the new treaty with a readiness to write off the old missiles. Today, Russia’s image benefits from the country’s desire to extend a treaty that is important for the entire world, and from the bold steps it has taken to meet its partners halfway. One example of the latter is the demonstration of the Avangard UR-100UTTKh ICBMs refitted with gliders, something that it did not technically have to do had it manipulated the definitions of the technology. Even though Russia is accused of all deadly sins, the current transparency mechanisms do not make it possible to levy clear charges of non-compliance with New START and to give media support to the Treaty’s opponents.

However, the long hiatus in nuclear arsenal control, the prospect of a prolonged arms race that will inevitably involve China (which has limited itself so far as, clearly, the country could have had far larger strategic nuclear forces, but has thus far preferred, instead of trying to catch up with the United States and Russia in terms of the size of its arsenal, to wait for them to reduce their own arsenals so that they are closer to that of China), and the general degradation of the global non-proliferation regime are all major dangers.

This period may begin in a year. Perhaps 365 days does not look quite as ominous as the Doomsday Clock that the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists set at 100 seconds to midnight, but 365 days is far more inexorable, and all of us becoming vegans will hardly help here.

1. A final act is traditionally adopted following the conference. However, the sides failed to do so on this occasion. The United States, United Kingdom and Canada refused to sign the act because it contained the requirement to convene a conference on eliminating WMD in the Middle East and declaring the Middle East a nuclear-free zone within a year. This requirement runs contrary to Israel’s interests.

2. The ban was introduced in 2014 and did not only concern the maintenance of the minefields in the Korean Demilitarized Zone.

3. Foreign sources and non-specialized media happily add Russia’s prospective anti-ship Zirkon missile here, but it likely does not have the necessary range.

4. The parties confined themselves to a vague cap of “1700–2200 units.”

5. In the 1950s and the early 1960s, the United States believed that the USSR had already built, or had the capability of building tremendous numbers of strategic bombers first and then ICBMs (tens and hundreds of times greater than the actual numbers) in the near future. This belief was used to put pressure on the military-political leadership of the United States to build up similar arsenals and be ready to use them first in the event of perceived danger.

6. Although during the Suez Crisis, the Soviet leadership confined itself to issuing diplomatic threats to the United Kingdom and France, the United States honestly believed that vast numbers of troops were being sent to the Middle East. In turn, the USSR linked the events in Egypt with the unrest in Hungary at the time and believed it to be the start of a massive attack on the socialist bloc, which explains why the uprising was so cruelly suppressed. The day before the intervention of the British–French coalition began, troops started to be pulled out of Hungary, and the Soviet government proposed opening negotiations with the new Hungarian authorities.

7. The Soviet military and political leadership perceived NATO's 1983 military exercise as possible preparations for a strike against the USSR. In his memoirs, then-President Ronald Reagan would write that he had been struck by the Soviet leaders' apparent belief in the readiness of the United States to start a nuclear war.

8. As of September 1, 2019, Russia had 513 deployed delivery vehicles (ICBMs, SLBMs, Heavy Bombers).