India’s Digitalization: Big Data is the New Oil

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 3, rating: 5) |

(3 votes) |

Ph.D. in History, Head of India Studies at the Moscow School of Management SKOLKOVO, Senior Research Fellow at RAS Institute of Oriental Studies

Over the last few years, India has travelled the path of rapid digitalization. Not only has the current crisis failed to stop this process, on the contrary, it has served to accelerate it in many areas and made some trends more evident.

Government efforts, active work by India’s business and joint steps undertaken by India’s public bodies and private entrepreneurs who are equally cognizant of the digital transformation’s significance, difficulties and prospects for India’s economy and society as a whole have advanced the process of shaping India’s new digital realities.

Internet access is, indeed, changing India’s image and lifestyle before our very eyes. Largely due to the decisive actions of the Indian businessman Mukesh Ambani, India has, in just a few years, made a qualitative leap in many digitalization-related areas while avoiding many intermediary stages that other countries spent years on. Only Indonesia outstrips India in its digitalization pace. In 2018, only China exceeded India’s number of digital consumers (560 million users).

The development prospects of India’s digital economy and primarily its consumer segment stimulated explosive growth of entrepreneurship that also relies on the traditionally strong stratum of India’s IT specialists. In 2017, Indian developers participated in creating over 100,000 apps for the App Store alone, while the total number of such apps is far higher, given that Indian specialists mostly create apps for Android.

There have always been many difficulties in working on the Indian market. Suffice it to say that, today, the majority of new Internet users in India do not speak English and need interfaces and content in regional languages. The country has 22 such principal languages. WhatsApp, for instance, supports 11 of them. Still, international investors bank on Indian tech companies, which is greatly helped by government bodies constantly working to stimulate the sector’s investment appeal. Companies working in e-commerce, digital payment services and tourism have long been the leaders in attracting investment among India’s tech startups.

Companies that appear not to have any tangible assets, not to make any money and to accrue debt are abound not only in developed countries but now in India as well, and still continue to increase their investment potential. Thus, they greatly befuddle traditionally-minded financiers. Yet, analysts increasingly have to admit that high-tech digital companies have unique sets of their clients’ big data, which allows these companies to increase their market share and make correct managerial decisions while constantly improving the functions or services they provide.

Big data is becoming more and more important for governments as well. The quality of analytical materials, development of AI technologies and efficiency of modelling processes depend directly on data volume used as a learning material; it can be used, among other things, to manage processes and resources efficiently in smart homes and cities. This is the purpose of Smart Cities, one of India’s government programmes.

Instead of demand for oil, the world is demonstrating a growing demand for innovation. Consequently, compared to other countries, India has every chance of becoming part of the process and a big-time winner. Russia’s business cooperation with India needs, like never before, to have its current realities supplemented in new formats, be it financial technologies, information security, artificial intelligence, sustainable energy infrastructure, advanced materials or other innovative areas.

Over the last few years, India has travelled the path of rapid digitalization. Not only has the current crisis failed to stop this process, on the contrary, it has served to accelerate it in many areas and make some trends more evident.

Government efforts, active work of India’s business and joint steps undertaken by India’s public bodies and private entrepreneurs who are equally cognizant of the digital transformation’s significance, difficulties and prospects for India’s economy and society as a whole have advanced the process of shaping India’s new digital realities.

In 2015, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the launch of the Digital India campaign spanning a series of key government initiatives such as increasing the people’s digital literacy, developing infrastructure and creating an e-government. The most significant achievements include completing and putting into operation the Aadhar digital identification system; a single taxation system covering all Indian states that previously had individual taxation rules; and the Reserve Bank of India, jointly with the association of Indian banks, developing and introducing an instant payment system similar to that created by Russia’s Central bank.

Nandan Nilekani, a well-known Indian entrepreneur and public figure, leads the committee on deepening digital payments at the Reserve Bank of India. An engineer by training, together with Narayana Murthy and several other entrepreneurs, Nilekani co-founded Infosys, one of India’s most famous and successful companies working in software development and IT consulting. In 2009, Nilekani left Infosys and wrote several books about India’s development and the way he sees its future: Imagining India: The Idea of a Renewed Nation (2009); Rebooting India: Realizing a Billion Aspirations (2015). He also headed the Unique Identification Authority of India, the government body that developed Aadhar, a digital biometric identification system, and introduced it throughout the country; Aadhar has already been mentioned; its importance for India is hard to overestimate. Digitalization has already resulted in tectonic shifts within a very short time-span, no more than 5-7 years, in such areas as India’s e-payments and financial technologies, e-commerce, telemedicine and entertainment. The spread of digital technologies has great significance and potential in such areas as agriculture, education, increasing energy efficiency, regulating employment and the labour market, transportation, logistics and further development of e-government.

Yet, none of that would have been possible had government initiatives not been backed up by the ambitions and strategic approach of another Indian entrepreneur, Mukesh Ambani, who swiftly provided Indians with cheap Internet and accessible smartphones. As he advanced his digital business initiatives, Ambani called upon Narendra Modi’s government to achieve maximum localisation of Indian data in India and spoke about the need to fight a new type of colonialism, the country’s informational enslavement by global corporations, so-called data colonisation. He devoted all his resources to developing a new sovereign digital platform; back in 2016-2017, Ambani already said that data are the new oil and smart data are the new fuel of India’s economy.

Following the sectoral liberalisation at the turn of the 20th-21st century, India created a telecommunication services market characterised by high competition among players (both Indian and international companies) that came to the promising area via partnerships with national bodies holding the requisite licences. By around 2010, most companies working in India saw that their revenues coming from traditional services might potentially drop, so they planned to transition to selling data. None of the many telecommunication companies on India’s market have, however, succeeded in the attempt. The failure stems from several factors, including the policies of the regulator (which decided to change the rules of the game and check the terms and conditions of previously issued licences at a crucial time for the sector) and appearance of a new player with the requisite resources, who was willing to spend them on achieving his large-scale goals. That player was Mukesh Ambani and his company called Jio. The history of Ambani’s family business is an integral and characteristic part of India’s economy, and the development track of his companies, including Jio, is regularly discussed in business media and is the subject of several business cases in the world’s leading schools.

Dhirubhai Ambani, the father of Mukesh Ambani and Anil Ambani, launched his business empire in 1957 with a small Bombay-based company importing synthetic fibers and exporting spices. In 1977, following its successful IPO, Dhirubhai Ambani’s Reliance Group became synonymous with business success and guaranteed financial investment for many Indians. The company did not confine itself to the textile business and became a diversified holding that also worked in exploring and developing hydrocarbons, in oil processing, petrochemicals, as well as energy, finances, trade and other areas. In fewer than 30 years, Reliance Group became a fixture of Fortune Global 500 and India’s biggest private company, rivalling such famous family holdings as Tata, Birla, Godrej, Mahindra. Dhirubhai Ambani died in 2002, leaving his sons a multibillion fortune. The brothers Anil and Mukesh engaged in a series of high-profile and unrestrained quarrels that resulted in Reliance Group’s assets being split in 2006. The telecommunication company Mukesh Ambani formed in 2002 had to be transferred, among others, to Anil, but Mukesh had the powerful oil processing business left under his control. His company was now called Reliance Industries. Its assets included the famous high-tech complex in Jamnagar (Gujarat State) processing up to 1.4 million barrels of oil a day. 2010 marked an important stage in this story, when the brothers agreed on revising the terms and timeframe for the non-compete agreements, and subsequently, Mukesh had a chance to announce openly his intentions to embark on a qualitatively new approach to the telecommunication business.

Digital Economy is the Economy of Innovations, not Inventions

It took Mukesh Ambani about six years to create a new company named Jio (Hindi for “live”). It was officially launched in September 2016. Back then, its telecommunication rivals realised that their already difficult situation would become far worse following the emergence of a powerful new player, but hardly anyone could imagine the cardinal and radical changes in store for the sector. India’s normally very active anti-monopoly agency, as well as other supervisory bodies, were prepared to close their eyes to many controversial points, since Ambani’s goals of swiftly spreading accessible Internet coincided with the course for digitalization steered by the government, while his statements that Indians’ data must be kept in India were very appealing for India’s political leadership. As of today, there are only two big players left in India’s telecommunication sector besides Jio, and these two are in a deep financial crisis. India’s government had to bail out both these companies by allowing large-scale foreign investment and by permitting all players to raise the prices for their services slightly, which had, over the last few years, fallen to an unprecedented low (between 2013 and 2017, the cost of 1 GB of data in India fell by 95%).

Today, Reliance Jio is part of the Jio Platforms holding company formed in 2019 as part of Reliance Industries. Mukesh Ambani’s two elder children hold top managerial positions in the family business. His son Akash, a graduate of Brown University, is in charge of strategy in Reliance Jio, while his daughter Isha, who graduated from Yale University, is on the board of directors in Reliance Jio and Reliance Retail.

The infrastructure and entire digital ecosystem of Reliance Jio was created and put into operation in under 2–3 years. The estimated costs of creating Reliance Jio vary between USD 20 and 45 bn., which is approximately the amount of Reliance Industries’ debt increase over the period of creating Jio. At the time of the company’s IPO in 2016, two-thirds of India's population of over 1.3 bn. had no Internet access. The company set the goals of deploying an efficient 4G network throughout India, including its remotest areas, while securing a large tech margin for future improvements, and of providing its clients with cheap smartphones and access to various contents and services through its own apps. In the first few months of its operations, while the equipment and all systems were being checked, cheap mobile devices under Jio’s own brand were literally handed out to customers free of charge. Later, minimal tariffs were introduced that immediately made India the leader in mobile operator accessibility for both voice services (phone calls were essentially free) and high-speed data transfer. Once sales took off, the company endeavoured to achieve 100 million new clients in the first 100 days, and did not slack off later: in the first two years, Jio had 250 million subscribers, and today it has 388 million. The company plans to reach 500 million users by 2021.

Jio has a large number of apps and services that have quickly become fixtures in the lives of Indians. They include JioTV, JioCinema, JioSaavn (a music service), JioMoney, JioCloud, JioFiber (broadband Internet access service). Jio rather efficiently provided digital functions to the conglomerate’s commercial line: Reliance Retail, which is also the leader in its segment in India. JioMeet, a video call service, is the latest addition to this extensive range of services. Reliance Jio’s contribution to increasing India’s per capita GDP is estimated at 5.65% in 2018.

Internet access is, indeed, changing India’s image and lifestyle before our very eyes. Largely owing to the decisive actions of the Indian businessman Mukesh Ambani, India has, in just a few years, made a qualitative leap in many digitalization-related areas while avoiding many intermediary stages that other countries spent years on. Only Indonesia outstrips India in its digitalization pace. In 2018, only China exceeded India’s number of digital consumers (560 million users). A survey McKinsey conducted in 2019 showed that the pace of data consumption per user in India grew twice as fast as in the US and China, increasing by 152% annually. Various estimates put an Indian user’s average data consumption at up to 9.8 GB of mobile Internet a month (this indicator is 5.5 GB in China, 8–8.5 GB in South Korea, and the 2019 figure in Russia is about the same). The number of Internet users in India was expected to grow by about 40% by 2023, to 750–800 million people, and the number of smartphones is expected to double, reaching 650–700 million (as of 2018, India had 1.2 bn. mobile subscribers). We can be sufficiently confident that new conditions arising from the pandemic will speed up these trends significantly.

India in the Era of Cyber Wars

The development prospects of India’s digital economy and primarily its consumer segment stimulated an explosive growth of entrepreneurship that also relies on the traditionally strong stratum of Indian IT specialists. In 2017, Indian developers participated in creating over 100 000 apps for the App Store alone, while the total number of such apps is far higher, given that Indian specialists mostly create apps for Android. In the entrepreneurs’ major league, 30 Indian digital high tech companies are unicorns (their capitalisation is over USD 1 bn., and they are still owned by their founders). In 2017, there were ten such companies. The crucial thing is that would-be unicorns in India are also quite numerous: in 2019, there were over 50 potential future champions.

There have always been many difficulties in working on the Indian market. Suffice it to say that, today, the majority of new Internet users in India do not speak English and need interfaces and content in regional languages. The country has 22 such principal languages. WhatsApp, for instance, supports 11 of them. Still, international investors bank on Indian tech companies, which is greatly helped by government bodies constantly working to stimulate the sector’s investment appeal. Companies working in e-commerce, digital payment services, and tourism have long been the leaders in attracting investment among India’s tech startups. A telling recent example of the international capital race for digital India was the USA’s Walmart acquiring Flipkart, one of India’s many digital e-commerce platforms, in May 2018. Walmart had long tried to gain access to India’s offline market, all to no avail, and it finally came to India by buying 77% of Flipkart for USD 16 bn.

Several investment funds of Russian origin are among those making big investments in India. They continue actively selecting new projects for investment and for strategy adjustment, as do other investors.

Companies that appear not to have any tangible assets, not to make any money, and to accrue debt abound not only in developed countries but now in India as well and still continue to increase their investment potential, thus greatly befuddling traditionally-minded financiers. Yet, analysts increasingly have to admit that high-tech digital companies have unique sets of their clients’ big data, which allows these companies to increase their market share and make correct managerial decisions while constantly improving the functions or services they provide.

Big data is becoming more and more important for governments as well. The quality of analytical materials, development of AI technologies and efficiency of modelling processes depend directly on data volume used as learning material; it can be used, among other things, to manage processes and resources in smart homes and cities efficiently. This is the purpose of Smart Cities, one of India’s government programmes. By late 2020, Jio planned to present commercial solutions for the Internet of Things. The company’s technical capabilities make this possible. While the Indian government is only preparing to make the decision on deploying 5G, Mukesh Ambani says that he has already built a new infrastructure capable of working with 6G and he is now striving to make India one of the principal beneficiaries of the 4th industrial revolution. Jio has no rivals in India in its capacity for collecting up-to-date data of Indian consumers and it plans to improve its technologies for their most prompt and precise processing and further use, while simultaneously developing cloud computing, smart devices, blockchain, augmented reality and more.

The current crisis arising from the pandemic is both shaping new consumer habits and bolstering demand for qualitative changes in approaches to the future economic development of many countries. This is also important for Russia, where, despite all the efforts to diversify its economy, there still remains the threat linked to dependency on commodity exports and the high energy intensity of other Russian exports. And it is also important for India, where 80% of its economy depends on imports of coal, oil and gas.

It was previously announced that 20% in Reliance Industries’ petrochemical business would be sold to Saudi Aramco, Saudi Arabia’s oil giant, for USD 15 bn. With oil prices falling to record lows, however, in March the deal fell through.

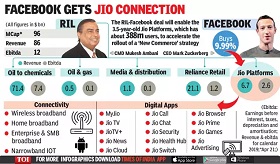

Instead of the Saudi Aramco deal, Jio Platforms finalised three different sales: 9.99% was sold to Facebook for USD 5.7 bn., 2.32% of Jio Platforms is now owned by the Vista Equity Partners investment fund (the stock is worth USD 1.5 bn.), and an additional 1.15% of the company’s stock was purchased by investors at Silver Lake Partners for USD 747 m. Mukesh Ambani still holds 86.54% of the company. Other deals with other investors are likely to follow, which will allow the Indian businessman finally to pay off Reliance Industries’ debt (about USD 8 bn.) by March 2021, without losing control of Jio Platforms, just as he planned.

In their official statements concerning the deals, all the participants, including Mukesh Ambani and Mark Zuckerberg, emphasize their confidence in the promising Indian market and in Jio Platforms’ potential. In full accord with the expectations of the Indian government and regular Indian citizens, they say that the new collaboration does not entail data exchange between partner companies. Jio, Facebook, Vista and Silver Lake also say they intend to use their technologies for the benefit of India’s small and medium-sized businesses by connecting such entrepreneurs more actively to e-commerce platforms. They are talking street trade and the so-called kiranas, typical Indian “neighbourhood” grocery stores; they will be able to find a more efficient digital way to meet their customers’ demand. Facebook-owned WhatsApp, which is very popular in India, is expected to play an important role in this process. If talks with the regulator concerning granting WhatsApp payment-making functions are successful, then, by pooling efforts with JioMart, the company will be able to expand both sellers and buyers' capabilities significantly and compete with India's most widespread fintech service PayTM, whose investors include Alibaba Group (the Chinese company owns 40% in PayTM).

India, with its 300 million users, is Facebook’s biggest market. WhatsApp has over 400 million users in India. As for the two other investors in JioPlatforms, Vista Equity Partners is noted for its major presence in India’s tech sector: its Indian companies have over 13,000 employees, while its co-founder Brian Sheth is a native of Gujarat, like Mukesh Ambani and Narendra Modi. Like Vista, Silver Lake is based in Silicon Valley and has already invested over USD 40 bn. in tech companies such as Airbnb, Alibaba, Ant Financial owned by Alphabet Verily and Waymo, and also Dell Technologies and Twitter.

Observers with a lively imagination have long since noticed that the company’s name, Jio, is a mirror image of the word “oil.” It is not known for certain whether this is by its founder’s design, but the events of the last few months and transactions around Jio Platforms confirm that, instead of demand for oil, the world is demonstrating a growing demand for innovations. Consequently, compared to other countries, India has every chance of becoming part of the process and a big-time winner. Russia’s business cooperation with India needs, like never before, to have its current realities supplemented in new formats, be it financial technologies, information security, artificial intelligence, sustainable energy infrastructure, advanced materials or other innovative areas.

(votes: 3, rating: 5) |

(3 votes) |

The Indian authorities striving to reduce the country’s dependence on tools developed aboard

India and Latin America: When a Rising Power and an Emergent Growth Pole EngageIndia and Latin America are embracing new strategic choices and diversifying into new strategic options towards recasting and transforming their once-staid mutual relationship

Digital Economy is the Economy of Innovations, not InventionsInterview with Vladimir Korovkin, Head of Digital and Innovations Research, Moscow School of Management SKOLKOVO