The key problems in the relationship between Russia and European Union are the lack of a clear-cut goal, a weak legal foundation and excessive politicization. The situation is not beyond recovery, but improvements will take time and cannot be achieved through top-down efforts. Energy serves as a litmus test for Russia-EU links in general, as it exposes their weaknesses and indicates ways to repair them.

Some Basic Points

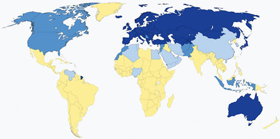

According to statistics, the European Union imports 36 percent of its natural gas, 31 percent of its oil and 30 percent of its coal from Russia. In view of the EU’s growing dependence on an external hydrocarbon supply, the figures seem quite impressive. In turn, Russia sends it 80 percent of its oil, 70 percent of its gas and 50 percent of its coal exports, which brings Moscow significant earnings. Hence, the partners are dependent on each other, rather than one being asymmetrically vulnerable before the other. Finally, the significant role of energy in their relationship is illustrated by the fact that oil accounts for 63 percent of Russia-EU trade, with gas accounting for only nine percent and coal for two percent.

However, the partners' energy cooperation is hindered by several factors, foremost among them being differing visions of how the sector should be best organized. As seen from its government document on energy strategy up to 2030, Russia is emphasizing budgetary efficiency, modernization and the stability of institutions. Meanwhile, the EU 2006 Green Paper focuses on liberalization, (i.e. encouraging competition through the rigid separation of production, transportation and distribution), as well on establishing a domestic market between its 27 member countries.

The second factor relates to different understandings of the nature of international relations. To a great extent, the EU’s actions are underpinned by the desire to extend not only its market mechanisms to its partners, but also its legal norms. However, it is worth noting that that the latter often fail to ensure optimum solutions even within the EU, and simply represent the conditions acceptable to the majority of its members at a given time. The extension of its law benefits the European Union, since it simplifies cooperation with third parties and the operation of European companies. As a result, the EU becomes the driver with its partners as passengers, without their individual circumstances being taken into account. All this contradicts the principle of equal partnership which is key to Russia’s foreign policy.

The Main Problems

1) The most significant problem is the lack of a clearly formulated goal for cooperation. The partners' aspirations have changed drastically since the 1990s, when individual obstacles to export were at the top of the agenda. Today, Moscow and Brussels are both aiming for a common energy market, as set forth by the draft EU-Russia Energy Cooperation Roadmap until 2050. However, the goals of operation cannot easily be clarified due to differences in perception of the energy sector and external activities. Brussels views the common energy market as a space liberalized to the greatest possible extent. Its staple is sterility of competition on the basis of common European rules. But the Russian focus is on maximizing profits, and this is guaranteed by means of control of gas pipelines built by Russian firms, and by access to the so-called "last mile", i.e. the EU end users, who offer the greatest profit.

The Russia-EU disagreements on aims of cooperation are most explicit in the sphere of gas. One example is the debate on the EU third legislative package, which covers pricing matters. It is worth taking note of the discussion on the principle of reciprocity – Moscow interprets it as common responsibility for shipments, whereas Brussels interprets it as universal rules and a liberalized market. In addition to the gas trade, the differences affect exports of nuclear technologies and electricity.

2) The energy sector is tied to an intricate combination of economics and politics, i.e. both to high profit and to national security. It gives rise to the politicization of issues, since the whole area becomes a subject of both economic cooperation and political competition. Political waves have engulfed the Moscow-Brussels relationship many times, provoked by the admission of new EU members and the suspension of gas deliveries.

Both sides support the depoliticization of energy issues, which is to say a purely economic focus, but their visions differ. The EU intends to integrate Russia into its market regime, while Moscow seeks to pragmatically maximize its earnings. From the perspective of the Moscow and Brussels paradigms, both approaches appear logical, but certain EU countries and institutions automatically interpret Russia’s rejection of European norms as a cause for politicization. Due to its foreign policy specifics, Russia sees the EU attitude as interference in domestic affairs.

Some EU states are more prone to politicization than others, which originates both from historical stereotypes, as is the case with Poland and the Baltic states, and from a lack of alternative gas supplies. Matters are aggravated by the fact that development of the infrastructure, in particular pipeline construction, lags behind the pace of liberalization. As a result, the domestic energy market exists only on paper, with only the legal preconditions being established.

3) Russia and the EU had two opportunities to establish a legal basis for international energy cooperation, namely the 1991 talks on the Energy Charter and the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty. Moscow was actively involved in drawing up the documents but refused to ratify the latter. The second chance arose at the 1994 negotiations on the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA), the core document for the bilateral relationship. Energy matters remained uncovered as the partners hoped at the time to specify the legally binding provisions in the Energy Charter Treaty.

Thus, a legal vacuum came into existence as early as the 1990s. The partners attempted to partially close the gap through the Russia-EU Energy Dialogue, which was initiated in 2000 and boiled down to the regulation of separate aspects of cooperation, as well as through the 2005 Roadmap on the Common Economic Space and the 2010 Partnership for Modernization initiative. To this day, energy constitutes one of the least legally detailed areas of Russia-EU cooperation, which only enhances the potential for politicization. It is no coincidence that energy is a key issue at the talks on the new basic agreement meant to replace the PCA. There, Brussels is doing its best to incorporate provisions for liberalization, while Moscow is working to retain freedom of action, and leave energy to be covered by a special protocol.

Are There Any Solutions in the Offing?

The lack of a concrete goal for cooperation, periodic politicization, and a lack of legal norms are the three problems the present author considers most significant for the Russia-EU energy relationship. They are interrelated and originate from (1) disagreements on the organization of the energy relationship, and (2) the EU drive to spread its law to Russia and the latter's resistance. These problems by no means threaten the hydrocarbon trade, but they do complicate the transition to a more integrated pattern of interaction.

The listed problems are surmountable, but they cannot be solved in a day, nor through top-down efforts. The way out lies through advancing grass-roots cooperation between energy companies, ecological organizations and researchers, so as to transform both sides’ perceptions. At the same time, it is already possible to suggest at least three steps that might ameliorate them.

First, the energy sector requires clear distinction of ends and means, with the ends being sufficiently concrete. First off, we have to define what we mean by a common energy market. Is it free movement of goods, services and, possibly, people? What kinds of contracts are feasible? At the same time, we need to leave room to choose different tools for reaching those ends while taking account of the partners’ individual circumstances. The mechanism which successfully operates inside the EU to allow for different preferences, cultures and economic structures between its members could also be helpful for the Russia-EU partnership.

Second, depoliticization, clarification of the goals of cooperation and the establishment of a legal foundation can all be facilitated by the diversification of relations. There are two core means: (1) raising energy efficiency and developing renewable energy sources (an area where the EU is already in the lead), which is in the centerpiece of the Partnership for Modernization, so as to balance the Russian leadership in the traditional hydrocarbon energy area; and (2) augmenting the interstate dialog on the top government and energy ministry levels with trans-government and trans-national dialog. Trans-governmental contacts imply the daily cooperation of officials at different tiers, as well as of the representatives of regulatory bodies. This practice is already used within the energy dialog and deserves expansion. Transnational ties involve the dialog between businesses, ecology organizations and independent experts. The focus on energy efficiency and renewable sources should provide this level of cooperation with enhanced dynamics as small- and medium-size businesses will become involved and seek to bring the issue of a transparent legal framework to the forefront.

Third, given the vagueness of the goals, there is no need to make haste with the inclusion of energy provisions in the new foundation treaty. Instead, the sides should employ the negotiation platforms of international structures in which both Russia and the EU participate on as full members. For example, energy issues are discussed by the G20 and the G8. Russia’s WTO membership should be of help, provided a strategy is developed toward the regional integration clause frequently used by the EU to insist on the supremacy of its norms. Moscow should think of returning to the Energy Charter Treaty if it is amended to account for its preferences as formulated in the draft Convention on Ensuring International Energy Security.

Cooperation within international bodies should also curb the EU's attempts to unilaterally extend its legislation to Russia. At international forums, partners negotiate the development of mutually acceptable mechanisms to be later incorporated into national law. This guarantees the equality of participants, as mentioned, a core element of Russia’s foreign policy.

Domestic policies should be also geared at the resolution of the Russia-EU energy relationship conundrum. To this end, improvement of the EU domestic market infrastructure could help depoliticize the dialog. No matter how strange it may seem, Russia benefits from shale gas production in Poland and the construction of the LNG receiving terminal in the Baltic. These costly projects will not provide a cheap alternative to Russian gas, but will provide potential for diversification and thus promote depoliticization of ties. Alternative gas and oil markets are important for Moscow, and its movement in the direction of Asia in this respect is a wise choice. The key objective here is enhanced self-confidence through a greater range of options.

To conclude, we should note that the aforementioned obstacles to energy cooperation also surface in other areas of the Russia-EU partnership. Clear distinction of ends and means (assuming the flexibility of the latter), diversification of relations through engagement of new actors and inclusion of new aspects, and switchover to international forums all offer workable prescriptions for spheres beyond energy. However, it is energy that will remain the litmus test for the overall Russia-EU relationship, while advances in energy cooperation will set the tone for economic cooperation in other fields.