In late October 2018, following the announcement by the President of the United States announce that the country was pulling out of the INF Treaty, the Russian International Affairs Council published a collection of articles on the collapse of the Treaty and the future of global arms control.

This article offers an overview of the statements made by the two parties in late November and early December, to provide fresher context. During the briefing held on November 26, Deputy Foreign Minister of the Russian Federation Sergei Ryabkov provided the most detailed explanation of Moscow’s stance on the INF Treaty throughout the history of the current crisis. In fact, it is a pity that such an explanation was not offered earlier. Ryabkov revealed certain details with regard to Washington’s accusations against Russia, and also shed some light on the 9M729 missile:

- The missile stands out for its warhead (which presumably differs from the 9M728/R-500, the standard cruise missile used in conjunction with the Iskander-M system).

- The missile’s range is within the INF requirements. On September 18, 2017, a 9M729 missile was launched to a distance of “under 480 kilometres” as part of the WEST 2017 exercises.

- Russia has supplied the United States with all the technical specifications for the missile, including information about its fuel system (to counter the assumptions of the American side that the missile’s range depends on how much fuel it carries).

- The test dates for the allegedly offending missiles provided by the United States do not correspond to the 9M729 test dates, which were announced five days before President Donald Trump’s announcement that the United States was pulling out of the INF Treaty.

All this leads us to the interesting conclusion that in the first half of the 2010s, the United States employed technical intelligence to observe parallel bench tests [1] of Kalibr-family long-range sea-launched cruise missiles and ground-launched Iskander-M cruise missiles, or of the Club-M coastal missile system, and arrived at the conclusion that these missiles were all part of the same programme. The information leaked about the alleged evidence held by the United States fits this theory nicely: originally, Washington asserted that Russia “initially test-launched a missile to a long range from an immobile bench, followed by a short-launch test from a mobile platform.”

Given the high technical similarity of these missiles, it may well have been the case that the Americans really did believe that the Russian side was in breach of the Treaty, whereas the Russians believed that their tests were completely legitimate. The 9M729 index was first announced by the United States in connection with the “offending” SSC-8 missile in December 2017, far later than the very first accusations levelled at Russia. In fact, Russian experts had long presumed that the United States was suspicious of this particular index (a number of sources hinted at the existence of such a missile and implied that it was developed by the Novator Design Bureau that did produce a cruise missile for the Iskander-M system). It is, therefore, possible that the Americans, in their search for “an upgraded Iskander missile,” stumbled upon it in this way or even extrapolated its existence by analysing discussions within the expert community. The rather comical situation cannot be ruled out that a missile differing in the warhead it can carry was taken to have a longer range simply due to cognitive aberrations and the United States’ urge to find a fault with Russia.

Russia also clarified its criticisms of the United States. As for target missiles, Ryabkov noted that not all test launches are followed by attempted intercepts, and that the mock-up warheads of these missiles are sometimes allowed to travel all the way towards their intended targets. As for UAVs, Russia is far from nit-picking: the United States is about to create a whole new class of weapons that are similar in nature to ground-launched cruise missiles. Regarding Russia’s efforts to develop such missiles, Ryabkov recalled a statement made by Washington that had gained popularity during the 2017 approval of the budget to create a new U.S. ground-launched cruise missile that the “development of such weapons is not prohibited.” As for the Aegis Ashore anti-missile systems and the associated Mk 41 launchers, Russia expressed its concern with Washington’s plans, as set forth in the latest Nuclear Posture Review, to develop a new nuclear-tipped sea-launched cruise missile that would be either a nuclear version of the Tomahawk missile or compatible with the Tomahawk launchers.

Subsequent developments demonstrated that Ryabkov’s statement came too late. The meeting between Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump on the side-lines of the G20 summit, at which the sides were expected to discuss the fate of the INF Treaty, never took place. Whether this was the result of the worsening Russia–Ukraine relations or Trump’s problems on the home front with regard to the so-called “Russian Case” (it was during the G20 meeting that Trump’s former attorney Michael Cohen announced he would cooperate with investigators) is beside the point. What is important is that the last possible chance to save the INF Treaty (if there ever was one) slipped away just like that. Instead, the United States intensified talks with its European allies, whose position was probably the main thing stopping Washington from abandoning the treaty.

On December 4, following a meeting of the NATO Ministers of Foreign Affairs in Brussels, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo presented an ultimatum to Russia, saying that the United States would pull out from the Treaty unless Moscow began complying with its provisions within the next 60 days. The United States specified later that Russia would be served with an official letter if the United States decided to withdraw from the Treaty. Washington’s allies pledged their support in the final joint statement and at Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg’s news conference. Although Pompeo did not specify whether the United States was going to comply with the INF Treaty during the mandatory six months following the possible pull-out [2] or stick with the proposal put forward by Congress to disregard the document completely, we may assume that Washington will not make a move until next August. But what will happen after that?

Super-Long-Range Cannon, Gunboats and Hypersonic Gliders

After that we are in for a feast of militarism and military engineering technology. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Director Steven Walker has assured the media that there would be “many flight tests” in 2019. So what kind of military technology is the United States busy developing?

The easiest technology to develop would be a mobile platform for ground-launched long-range cruise missiles. This possibility was first mentioned in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 and was subsequently reaffirmed in the document for 2019. An existing cruise missile should have already been selected for the new system (the main bidders being the sea-based Tomahawk and the air-launched AGM-158 JASSM, but no information has been revealed about the development effort over the past year. Tomahawk has a greater range, whereas the JASSM offers better survivability thanks to its lower visibility. The United States has also announced plans to create a new, longer-range JASSM missile, codenamed JASSM XR, which will likely be closer to the Tomahawk in terms of its range, at about 1600 to 1700 kilometres. The JASSM could win this contest because the new system is being developed for the United States Air Force, owing to the division of functions between the different branches of the country’s armed forces. It was the Air Force that operated the ground-launched nuclear-tipped Tomahawk, known as the BGM 109G Gryphon, which took part in the Euromissile crisis in the 1980s.

Ground-based conventional cruise-missile systems are often criticized for being of little use given the existence of naval platforms for such munitions, which are particularly ubiquitous in the United States. This argument disregards a number of advantages presented by overland launchers, including the lower cost of ground platforms, lower operating expenses per launcher, the possibility of replenishing the stock of missiles in the field (ships can only reload their vertical launchers at home base), and also their greater viability in combat, with the dispersed and camouflaged launch and command vehicles being impossible to take out with a single anti-ship missile.

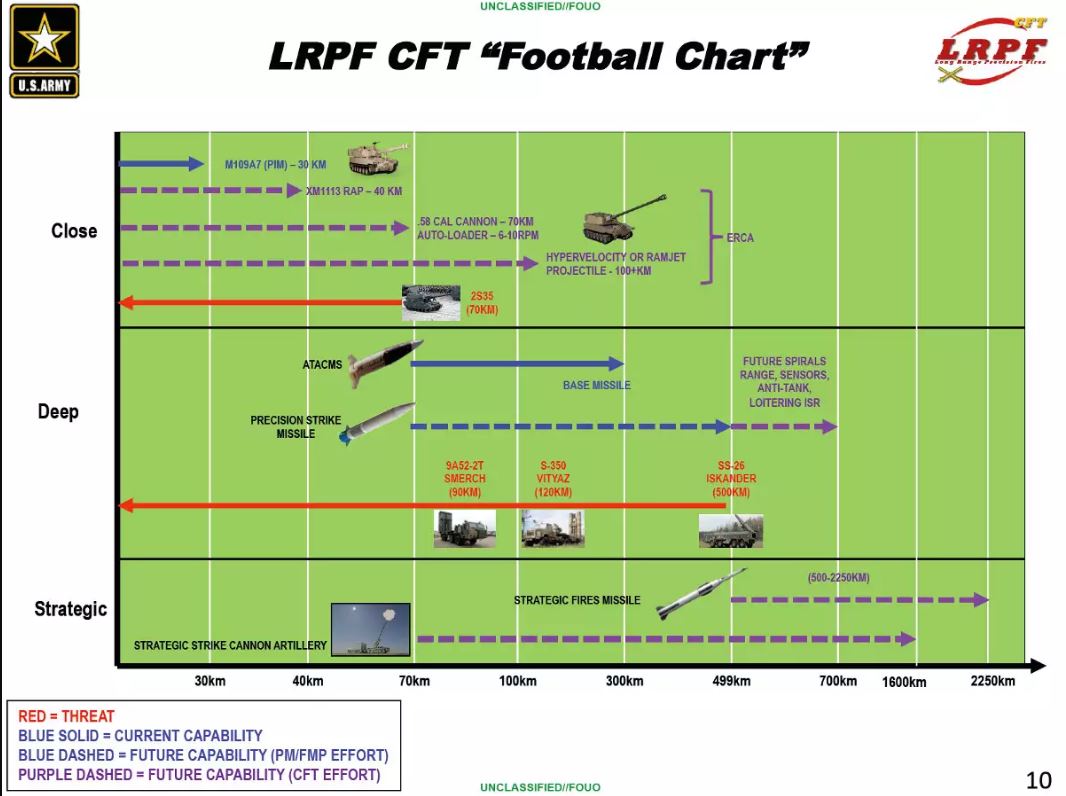

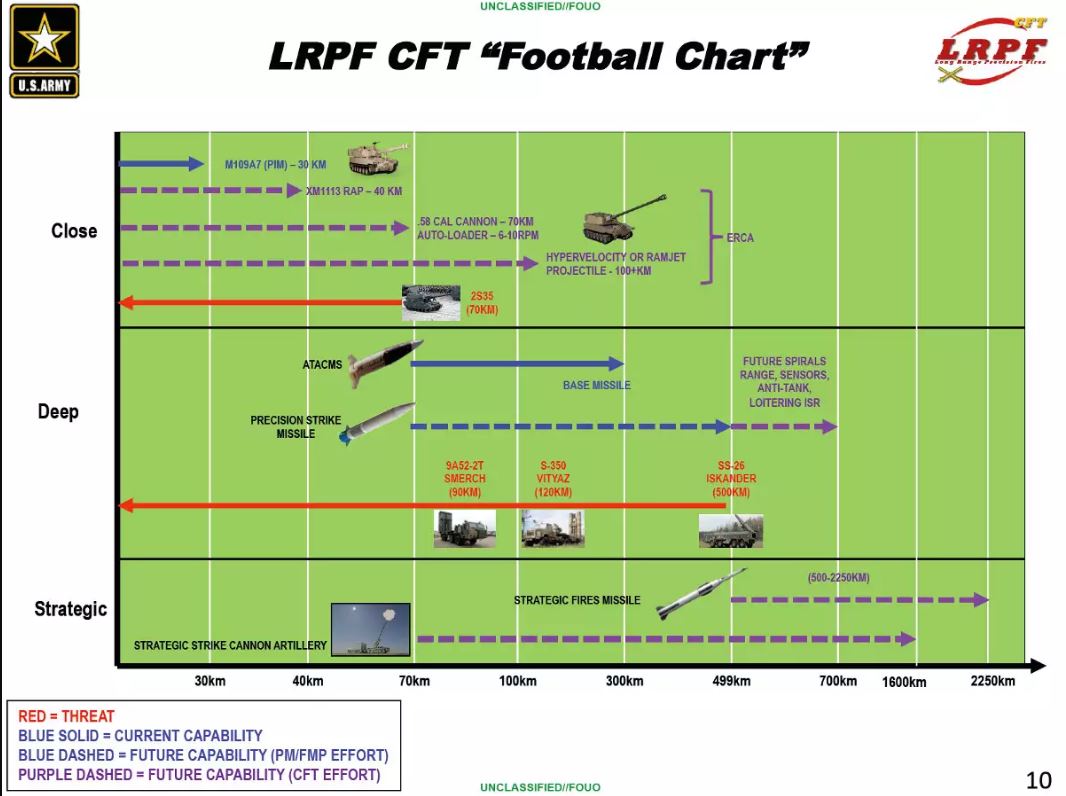

There is, however, more to come, as announced by Pentagon in 2018. The mainstream media were particularly intrigued by the programme to develop the Strategic Strike Artillery Cannon with a range of 1000 miles. Of course, we are not talking about the kind of cannon that Jules Verne wrote about in his novel From the Earth to the Moon, nor are we referring to the kind of “superguns” envisioned under Saddam Hussein’s Project Babylon. Rather, the U.S. programme is about creating a launcher for ultralight precision missiles. Such a system would provide the United States Army with an opportunity to instantly destroy small-sized targets in any operational theatre. It is, however, important for the programme’s success to keep the operational costs within reasonable limits.

More important, though less attractive, is the Strategic Fires Missile programme. Although touted as a “fundamentally new” type of weapon, it is in fact another Pershing missile: a conventional missile with a range of 2000–2250 kilometres and a precision hypersonic glider warhead. This would certainly be classed as a medium-range ballistic missile, and it is this programme that DARPA is focusing on. The United States Army has long been working in this sphere as part of the notorious Prompt Global Strike initiative. Back in 2011, a prototype glider was successfully tested under the Advanced Hypersonic Weapon (AHW) programme.

U.S. Department of Defense

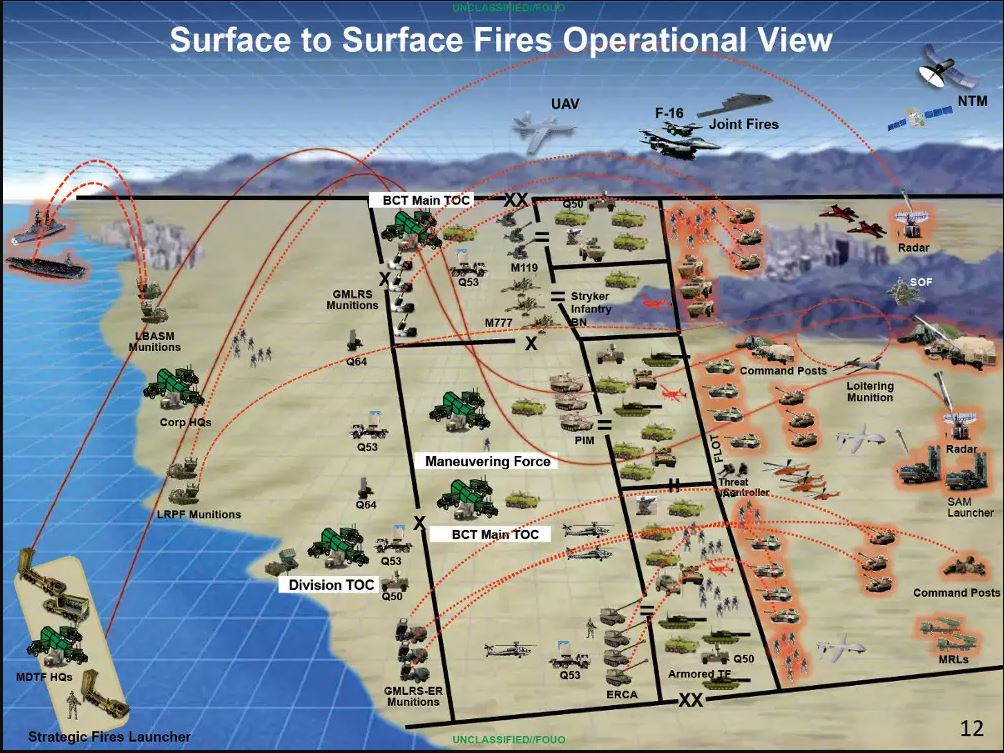

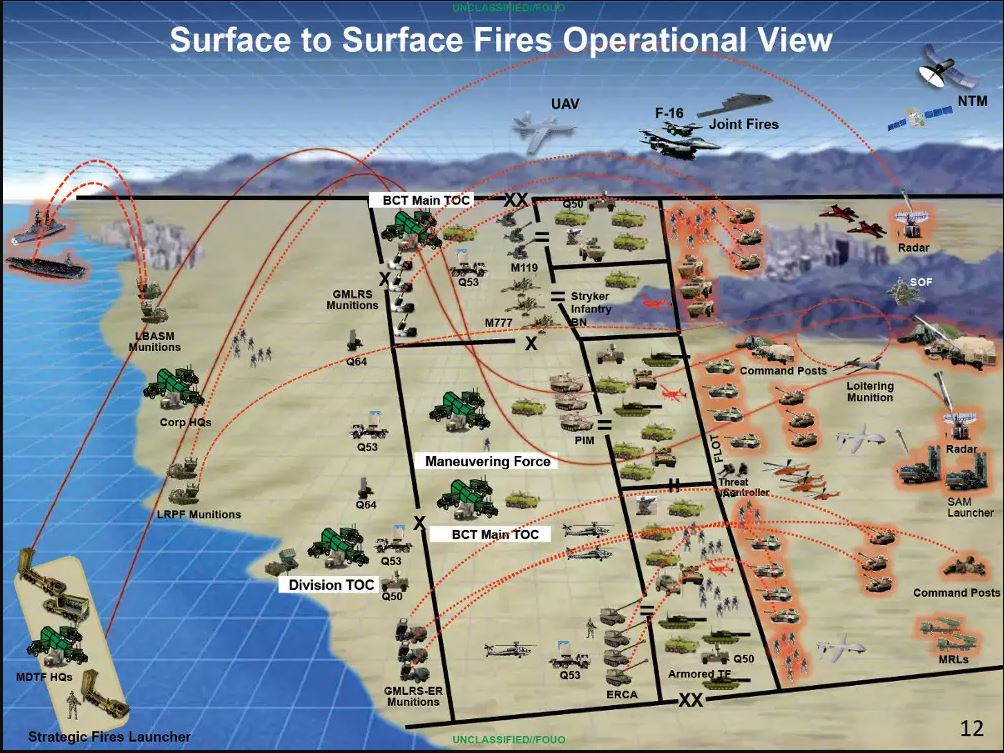

Surface to Surface Fires Operational View

Hypersonic research in the United States is not limited to army projects. There are several parallel programmes to create air-launched aeroballistic missiles with gliding warheads that are to be added to the Air Force’s inventory in the early 2020s. One of these is known as the AGM-183A AARW. It will most likely be carried by B-52H bombers, whose underwing hardpoints will be upgraded to accommodate an increased payload of 9 tonnes. The United States Navy is developing its own medium-range ballistic missile with a glider warhead, primarily for Ohio- and Virginia-class submarines. Lighter missiles could be developed for Zumwalt-class destroyers, whose original role as gunboats seems to have failed to materialize due to problems with the onboard cannon (to be more precise, each of their guided projectiles comes at half the price tag of a cruise missile). On the other hand, the Zumwalts could use reinforced vertical Mk 57 launchers. The three branches of the armed forces are expected to share their developments: it is known that the Air Force and possibly the Navy will be using the Army’s lighter and more advanced glider, whereas the heavier naval glider will eventually be added to the Army’s inventory.

U.S. Department of Defense

It should be noted that all the aforementioned programmes are conventional, at least officially. U.S. officials dismiss accusations that they are attempting to launch a new nuclear arms race; in fact, there are many open critics of this scenario among the country’s legislators (the Democrats, who have seen their positions in Congress consolidated, are even threatening to thwart Trump’s more conservative proposals on nuclear weapons). It should, however, be remembered that it is far easier to turn a conventional missile into a nuclear missile than vice-versa (a quality nuclear charge is lighter and smaller than the average conventional warhead, and does not have to be as accurate). Should the United States continue with its course towards confrontation with Russia or China, this conventional-to-nuclear transition would be easy to make. Besides, there is nothing optimistic about the creation of conventional strategic-range missiles, because they are psychologically easier to resort to in a conflict, and such an escalation could be very dangerous.

It is clear that, for reasons of geography, the United States only needs missile systems that breach the INF Treaty for purposes of advanced deployment. Such missiles could be deployed primarily in Southeast Asia to counter China. It may be uncomfortable for Russia to admit, but Washington is using Moscow’s alleged breaches of the Treaty chiefly as a pretext for opposing Beijing, which is something the U.S. authorities have been openly talking about for the past several months [3]. It would also come in handy to have some missiles in the Middle East: there is no reason to believe that the region will become peaceful in the foreseeable future, so ground-launched missiles would help relieve some of the burden currently carried by the local naval and aerial forces. The Arab monarchies, which are anxious about the Iranian threat, would be happy to receive such missiles.

The key issue for Russia would be the possible deployment of U.S. missile systems in Eastern Europe. Subsonic cruise missiles are not likely to change the current state of affairs in any significant way (the United States and its allies are already capable of deploying significant numbers of such munitions on naval and aerial platforms if needed), but precision medium-range ballistic missiles capable of reaching any target in European Russia would be unwelcome near the country’s borders. Both Russia and the United States are currently assuring each other that they have no intention of starting another European missile crisis, and Washington stresses that it has no plans to deploy its missiles in Europe. However, as Ryabkov noted at the briefing, these plans may change at any moment so cannot be taken for granted. It would, of course, be nice to agree on an area, “from Lisbon to the Urals,” that would be free of new missile systems. This would not prevent the sides from promptly deploying such systems near the adversary’s borders within a couple of days, but such deployment would come as a consequence of a crisis and not as its cause.

However, the two countries have yet to come up with the new political rules of the changed game, and we are left to hope that they will do so quickly. It would be useful for Russia to assume a more active position compared to the one it demonstrated during the INF Treaty crisis, as well as to step up work, primarily with European countries, which are concerned about the possibility of a new missile crisis on the continent.

Russia’s possible R&D response to Washington’s withdrawal from the INF Treaty merits a separate detailed article.

1. For the sake of practical convenience, the signatories to the INF Treaty permitted each other to bench-test their ground-launched cruise missiles at one testing centre per country.

2. On the evening of December 4, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation tweeted that the U.S. Ambassador had submitted a note stating that the United States would stop observing the INF Treaty within 60 days. This circumstance further complicates the situation, though it is insignificant.

3. Trump also mentioned China as one of the reasons why the United States was going to withdraw from the Treaty, whereas John Bolton stated in no uncertain terms during an interview in Moscow that even if Russia stopped breaching the treaty (which, according to him, was impossible because Moscow was in denial), then the United States would still have to pull out unless China joined the Treaty and destroyed most of its nuclear missile potential, which would certainly never happen.