In January, Iran marked the first anniversary of the lifting of the majority of international sanctions. The Islamic Republic took a short breath of economic freedom. However, after the D. Trump administration set up in the White House, dark clouds started gathering over Iran, posing danger to its economy and energy sector. What did Iran achieve during the one-year period of hope and freedom? What do international investors, including Russian companies, make of Iran’s energy prospects?

Did Iran fulfill its promises?

Most of the promises the Iranians were making in the run-up to the sanctions being lifted dealt with oil production and exports. In July 2015 – right before the JCPOA was signed – Iran produced around 2,85 million barrels/day (mbd). At that time, local companies and the government claimed they could increase production up to 4 mbd in three months after the sanctions were lifted, i.e. by March 2016. In statements addressed to the international audience the timeline was somewhat different – 4 mbd by June - September 2016.

Iran has almost fulfilled its plans of oil production, though with a slight delay. According to the latest OPEC statistics, in December 2016 Iran produced 3,7 mbd, as reported by secondary sources, or 3,9 mbd reported by direct communication. The Iranian government pledge to hit the level of 4 mbd by mid-April 2017.

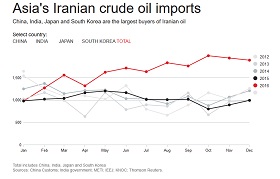

Over the year, Iran managed to win back its market share. According to the U.S. EIA, Iran’s exports of crude and condensate amount for 2,4 mbd, which is twice as much as it exported while under sanctions. Historically, China, India, Japan, and South Korea are the biggest importers of Iranian crude, and they were at the forefront to increase imports from Iran in 2016. The European market followed their lead. Bloomberg reported that in January 2017 European states bought 600 thousand barrels of Iranian oil per day. No longer than a year ago, this figure was equal to zero.

Not only is Teheran boosting its exports to old, established clients, but it is also testing new export destinations. Thus, 2016 saw the first Iranian oil cargo delivered to Poland, with the two biggest refineries being the buyers (before, these refineries relied on Russian crude). Poland did not rule out the possibility of striking a long-term oil deal with Iran. In February 2017, news broke about Iranian crude sale to Belarus.

Despite its huge gas reserves, Iran has never been a major gas exporter. Iran’s gas industry is primarily focused on the ever-growing local market. The gas is also essential for oil production, as 17% of the produced natural gas is pumped into the oilfields in order to increase their output. Gas consumption in Iran is growing, and it is growing fast. This means that Iran will keep its focus on gas production and refinery projects that target first and foremost domestic demand. In the mid-run, Iranian gas is unlikely to reach any markets further than those of the neighboring Iraq, Pakistan, Oman, and India. The transport infrastructure linking Iran to these countries is at different stages of construction.

All in all, by February 2016 Iran had shown considerable progress: oil production and export indicators had almost reached the levels promised by the government. Yet it looks like without the inflow of international investment into the sector, any higher altitudes of production are not reachable for Iran. Exhausted by the years of sanctions, Iran’s energy industry needs immense investment and technological renewal along the whole chain from oil and gas exploration, to their refining and electricity generation.

Perhaps Iran’s November 2016 decision to participate in OPEC’s oil production cuts was possible for the very reason that Iran has no technical capabilities to increase oil output any further. Then, Iran committed itself to limit oil production growth by 90 thousand barrels/day till June 2017, surprising many experts. However, it might be that Iran never went out of its way to accept the deal, and the decision was driven by the understanding that the nation will not be able to increase daily production by more than the said 90 thousand barrels. At least not until international companies embark on investment.

International investors: who returned, who is waiting, and who changed their mind?

The nuclear deal merely cracked open the Iranian front door to international investors, yet an overwhelming amount of them hurried to squeeze in. The number of business delegations, representatives of international companies and governments that visited Iran in 2016 alone is beyond counting. The crack in the door gave companies an opportunity to assess Iranian projects and claim their place in the Iranian sun. However, the majority of oil and gas deals signed so far are of preliminary nature.

Over the past year and a half, world-leading energy companies signed memorandums of understanding and other provisional agreements with Teheran. In January 2017, these companies were successfully prequalified for Iranian upstream tenders. The list of approved companies includes, but is not limited to, Russia’s LUKOIL and Gazprom; European Shell, Eni, Total, OMV; American Schlumberger (the only U.S. company in the list); Chinese Sinopec, CNPC, CNOOC, CNPW; as well as the major companies from Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan, and India.

The popular sentiment among Russian experts and the public was that Russian companies may be the first in line for getting the best deals as a testimony to the developed cooperation between Russia and Iran and the similar stance they take on a number of global and regional issues. Such expectations are right, but only to a certain extent.

Iran has made it clear that it is primarily interested in adopting modern technologies that would push the renovation of its energy industry. This is more than a mere bromide or a put-on sham affirmative attitude inherent in populist political statements. In fact, Iran is used to being independent and self-sufficient while living under sanctions. For instance, an Iranian oil company is the largest tanker owner in the world, managing far more oil tankers than any of its neighboring fellow oil exporters. This allowed Iran to overcome the sanctions that targeted its oil trading activities by prohibiting international banks from insuring oil trade with this country. There is hardly anyone who is more aware of the necessity of making national industries more independent and developed than the current oil minister Bijan Namdar Zangeneh, who, in recent decades, led the most vital national ministries during the hardest periods of Iran’s post-revolutionary history.

There is also no doubt that the investors most welcome are those with strong financial capabilities, who are in position to allocate additional financial support for the projects. It is no coincidence that Japanese and Chinese companies have the best representation in the list of pre-qualified companies: they have sufficient financial capacity to lend money, and more so on strategically important energy projects.

Despite the shortage of cutting-edge technology and comparatively weak financial capabilities, Russia has good chances of winning some profitable contracts in Iran. Drawing from the example of a nearby Iraq, political ties and diplomacy might be of great help to promote the positions of Russian companies in a country. As Fedor Lukyanov rightly put it, Russia should not trade its close ties with Iran for the hypothetical possibility of ameliorating its relations with the United States. This option is unacceptable for both geopolitical and economic reasons. In the end, being present in the oil and gas industry of your competitor is a worthy economic tool. In this context the recent visit of Iranian president Hassan Rouhani to Moscow on March 27-28th seems to bode well for the cooperation between the two states[i].

Back to international investment, it is worth noting that the finalization of upstream deals was impeded by two factors. First is the failure of Iranian legislators and its government to agree on the legal framework for international oil and gas investment. For more than a year and a half, the investors have been waiting for the new type of standardized contracts – IPC (Iranian Petroleum Contracts) to be finalized. No luck so far. The official presentation of the contracts was postponed several times, to September 2016 first, then to spring 2017, and now stymied by the upcoming elections.

The second barrier for investment is the still-not-lifted American sanctions. The limitations still preserved are mostly those put by the U.S. government as a reaction to the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, targeting the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. This, in turn, makes international companies operating in Iran wary of the possible American sanctions. To avoid the risks, multinationals have to solicit approval of the U.S. Treasury to do business in Iran. International business, banks in particular, are apprehensive of suffering the same fate as French BNP Paribas, which had to pay a fine of as much as 9 billion U.S. dollars to the U.S. Department of Treasury for doing business with Iran.

Moreover, international companies still struggle to use U.S. dollars in operations with Iran. Teheran often recurs to using other currencies for financial transactions. Reportedly, Iran used euro as the main currency for oil sale to French Total, Spanish Sepsa, and the trading arm of Russian LUKOIL Litasco. Because of the “dollar barrier”, some international corporation have not yet paid their debt to Iranian companies for the oil delivered before 2011. In other cases it is vice-versa, Iranian companies have not yet paid their debts: for instance, Iran still owes Italian Eni.

Besides, Iranian business has to show creativity in finding ways to get access to loans and insurance. At the end of 2016, oil trader Vitol provided Iran a 1 billion U.S. dollar loan against the guarantee of oil supplies, with the more traditional types of insurance being hard to arrange.

However, a much bigger issue than any of those those mentioned above was needed to scare away some of the investors. In January 2017, global energy major BP announced its decision not to pursue its participation in Iranian upstream tenders, allegedly concerned with the possibility of the return of international sanctions. It seems that the decision was well thought-through, as the company had even created a group that was charged with studying the prospects of Iranian contracts. Moreover, the group did not include the head of the company, who holds American citizenship – a move insuring the immunity from the U.S. sanctions.

Iran-US relations on the edge

By the fall of 2016, it became clear that in the long-run the success of Iranian energy is contingent upon two factors: the policies of the new American administration toward Iran and the results of the Iranian presidential election (to be held in May). These two factors will determine whether the Iranian nuclear deal will be preserved and whether the Iranian economy will still be free of international pressure.

As of February 2016, one of those variables started to take shape, and though not distinct yet, the indications are definitely negative. Donald Trump’s public announcements are ambiguous and often contradictory, however the make-up of his cabinet does not bode well for Iran. The Pentagon chief James Mattis is strongly against the JCPOA. The same is true about the new CIA Director Mike Pompeo, the Vice President Mike Pence, and the recently resigned Michael Flynn. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson is one of the handful of people who have a rather neutral take on the Iranian deal. The first orders signed by D. Trump reassured the doomsayers of the Iranian deal that the agreement will not last much longer.

Today, the USA is the only signatory of the JCPOA that argues against it. Iran, the EU, Russia, and China have all made it clear that they support the deal in its current form. The head of the EU’s foreign policy, Federica Mogherini, claimed she had personal responsibility to ensure that the agreement is implemented by all sides. She pointed out that it should be taken into account that there are four other parties to the deal except Iran and the USA – the EU, UN, Russia, and China – adding that it is not in U.S. power to unilaterally end the deal. The Wall Street Journal reported quoting unnamed sources that in November-December 2016 the EU sent its representatives to the United States in an effort to convince the newly elected President to preserve the deal.

In Europe it is France that shows the greater willingness to keep the JCPOA. According to Bloomberg, French companies have recently been the biggest European buyers of Iranian oil. France is also eager to get into upstream and midstream projects in Iran. The January visit of a big French delegation to Teheran led by Foreign Minister J-M. Ayrault looked almost like a reaction to the rigid stance towards the Islamic Republic adopted by the USA.

However, as the Carnegie expert K. Adebar has aptly pointed out, whether we like it or not, the survival of the JCPOA depends on the benevolence of only two parties – the administration of the USA and that of the Republic of Iran. The problem is that American actions may affect greatly the political situation in Iran, undermining the position of the Iranian reformists; those who lobbied the JCPOA and supported the return of international investment.

Meanwhile in Iran

On May 17th 2017 the Iranians will elect a new president. As a result, a far less Western-world-friendly administration might come to power. The incumbent president, Hassan Rouhani, has already registered his candidacy, yet his return to office is not guaranteed. The conservatives, who traditionally oppose international investment into the national economy, are strong opponents.

Today Iran is working on the liberalization of its legislation, adjusting it to attract international investment. As for the oil and gas laws, the promise is that the new IPC will be more investor-friendly than the formerly used buy-back contracts.

Apparently, the struggle for the shape and content of the international investment-related legislation is far from over, and it involves a great deal of “bargaining”, both between Iranians and multinationals, and inside the Iranian elite. Let us accentuate that not everyone in Iran is happy with the lifting of sanctions; indeed far from everyone on the conservative side. Most of the conservatives are affiliated with the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, and they advocate a decrease of the rights for international investors, if not their total ban from entering Iranian projects. Highly experienced, influential, and a strong manager, the oil minister B.N. Zangeneh is the most important at playing the role of a mediator between the contesting parties. The fact that this man is in charge of the oil ministry is by all means propitious for international investors. B.N. Zangeneh has always been in favor of international capital coming to Iran, which proves his ability to compromise and his inclination to find solutions. At least as much as this is possible amid the great political pressure he is facing at home.

This is why the recent attacks of the U.S. administration on the Iranian nuclear deal are so perilous and destructive. Not only does it perturb the investors, but it also strengthens the positions of the Iranian conservatives right before the election. The previous time conservatives came to power – in 2005 – the oil and gas sector of Iran entered a new period of degradation caused by the imposed sanctions and an unprecedented increase in the administrative body of the ministry of oil, which incorporated literally thousands of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard members (close to the president M. Ahmadinejad). If the current reformist cabinet spearheaded by president Rouhani, foreign minister J. Zarif, and oil minister B.N. Zangeneh departs from power, the future of the oil and gas sector of Iran might be doomed.

The Iranian government claimed its oil and gas sector needs 180-billion-dollars in investment by 2022. The head of Eni speculated that the Iranians needed 150 billion dollars. Whatever the sum is, it is sure that the energy sector of Iran will not be able to fulfill even half of its great potential without vast international investment.

The analysis leads us to three possible scenarios. Under the first – negative – scenario the USA leaves JCPOA which sparks an antagonistic reaction from Teheran. The return of American sanctions strengthens the position of Iranian conservatives, and all that combined inevitably throws the Iranian economy and its oil and gas sector back to isolation.

Under the second scenario, the USA and Iran stick to the nuclear deal. However, the sense of precarious unpredictability about Iran’s future affects the sentiment of international investors. The long-run repercussions of this scenario are tantamount to that of the first one. Here, the lack of economic development caused by the dubious political situation will drive the resentment among the Iranian population, who had traded the national сrown jewel – its nuclear program – for the economic development that never came. The resentment, once again, will strengthen the conservatives, whose stride will hinder any international investment in the oil and gas sector.

The third, or positive, scenario is possible if international actors put enough pressure on the Trump administration. Russia should take a hard-line attitude and use all the tools available to ensure the compliance of the JCPOA signatories to the terms of the deal. If the agreement survives and the reformists remain in power in Iran, the plan to attract investment to this country is sure to succeed. International business will enter Iranian upstream projects under any oil prices, regardless of the underdevelopment of its infrastructure or the high level of corruption. If only the specter of sanctions is not haunting Iran anymore, the pearl that is the Iranian oil and gas sector will finally reveal itself for the whole world to see.

[i] No energy deal was signed, though the parties claimed that they touched upon energy-related issues.