U.S. Public Perception of Russia: Friend or Foe?

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

PhD in Politics, Center for Domestic Policy Research at RAS Institute for the U.S. and Canadian Studies, RIAC Expert

Public sentiment in the United States and the perception of Russia in American society are important factors in Russian-U.S. relations. Natalia Travkina discusses the change in U.S. public opinion and how it affects Washington’s policies toward Russia.

November 16, 2013 marked 80 years since the USSR and the United States established diplomatic relations. By far the most telling element in this anniversary was that it did not even deserve a mention on either the US State Department’s website or that of the Russian Foreign Affairs Ministry. Symbolically, on November 15, on the eve of this event, the U.S. Department of State published a statement commemorating the fourth anniversary of Sergei Magnitskiy’s death, claiming that the Russian authorities failed to bring those responsible to justice. The statement ended by saying that the United States will “continue to fully support the efforts of those in Russia who seek to bring these individuals to justice, including through implementation of the Sergei Magnitskiy Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012.” [1]

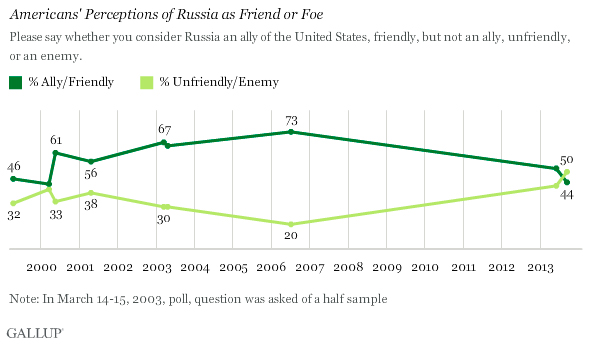

The statement by the U.S. State Department carries significantly more meaning than it seems at first glance, as it effectively sets a new reference point for the U.S.-Russian relationship – November 16 2009, instead of November 16, 1933. This will continue, in the coming years, to set both the tone and the overall environment for the relationship. This deterioration in Russian-American relations was accompanied by a major swing in the U.S. public perception of Russia. In fall 2013, for the first time this century, respected pollster Gallup recorded a higher proportion of U.S. respondents that have a negative opinion of Russia: 50 percent against 44 percent giving positive views. The graph below shows the changes in U.S. public sentiments toward Russia between 1999 and 2013.

Chart. Changes in U.S. public opinion of Russia in 1999-2013

Swift A. For First Time, Americans' Views of Russia Turn Negative Despite approval of Russian plan for Syria, Americans sour on Putin. September 18, 2013. − http://www.gallup.com/poll/164438/first-time-americans-views-russia-turn-negative.aspx.

When probed, U.S. public opinion over the past 15 years has had a demonstrable causal effect on the U.S.-Russian relationship, shaping the changes in U.S. sentiment towards Russia. In the Gallup survey, positive or negative attitudes to Russia were gauged based on the question asking whether respondents viewed Russia as an ally or a U.S.-friendly nation, or, on the contrary, as an unfriendly nation or even as America’s enemy. In 2001-2012, when the United States was waging a global war on terror, as the chart clearly shows, U.S. public opinion shifted noticeably in Russia’s favor in the immediate aftermath of 9-11, when Russia joined the United States in an alliance against the threat posed by global terror. The perception of Russia as an “ally” peaked in 2006-2007 (practically 4 to 1 among the respondents), i.e. when the U.S.-led military campaign in Iraq and Afghanistan was at its height.

Under Barack Obama, the United States started to downsize gradually its war efforts in the Middle East, and, as a result, there was less need for anti-terror allies, something that was true of Russia and of the NATO countries involved in the Iraq and Afghanistan operations. Significantly, the turnaround in U.S. public perception of Russia took place on the eve of 2014, the last year of U.S. troop deployment in Afghanistan. Additionally, recent years have also been marked by growing differences between the United States and Russia over Syria and Iran.

As a result, now that the “common enemy” that served to bring the U.S. and Russia together is vanishing, the emphasis today is increasingly placed on ideology, in the form and shape of human rights issues. In this context, Gallup has listed three factors among the key reasons for the radical shift in U.S. attitudes toward Russia recorded in fall 2013: Russia offering political asylum to former U.S. intelligence contractor, Edward Snowden; restrictions on sexual minorities’ rights; and the New York Times’ publication of an article by President Vladimir Putin in which he labeled statements by leading U.S. decision-makers about American exceptionalism as "extremely dangerous" [2].

The Gallup results are corroborated by a poll conducted by the respected Pew Research Centre and also published in early fall 2013. In fact, the Pew Research Centre poll shows that negative perceptions of Russia in the United States are less prominent than Gallup researchers believe. According to the Pew Research Centre poll, 43 percent of respondents against 37 percent have a negative opinion of Russia; however, there is also a marked age gap in attitudes toward Russia within the United States: 49 percent of respondents aged between 18 and 29 view Russia positively, but the proportion of people giving this answer falls in older groups of respondents: 38 percent of respondents aged between 30 and 49, and 29 percent among those who are 50 and older [3].

Thus, the Pew Research Centre poll demonstrates quite convincingly that, in today’s American society, public opinion about Russia is dominated by Cold War stereotypes and clichés. Indeed, Washington’s reliance on Cold War rhetoric has helped revive some common dogmas that the older age groups lived with for most of their adult lives during the 20th century.

The ‘Reset’ as a Strategy for Change in Russia’s Political Elites

The perception of Russia in American society worsened progressively through President Obama’s first term in office, despite the ‘reset’ in Washington-Moscow relations pushed by the White House, followed a split in how this policy was interpreted by public opinion and the U.S. expert community. Officially, the administration announced its commitment to the principles of equal relations and mutually beneficial cooperation, but in essence, the two presidencies that started almost at the same time – that of Barack Obama (from January 2009) and that of Dmitry Medvedev (from May 2008) – were perceived by U.S.-Russia observers as part of a course aimed at aiding a gradual shift in Russia’s political elites. A similar strategy had already been used in the early 1990s in U.S.-Soviet relations, and then again in the late 1990s – early 2000s in U.S.-Russian relations, in both cases with an outcome favoring the United States.

In 1991, following the Russian presidential election in June 1991, President George Bush’s Administration backed Boris Yeltsin and dropped Mikhail Gorbachev. In 1999, President Clinton’s Administration, which raised concerns over money laundering through the Bank of America by “corrupt Russian political elites”, facilitated President Yeltsin’s early resignation in an attempt to completely exclude the “Russian factor” from the 2000 presidential race. In Clinton’s Administration, the U.S.-Russia relationship was delegated to Vice-President Al Gore, who later won the Democrat nomination to run for president. The question “Who lost Russia?” then became a crucial element of the domestic political agenda.

A similar approach to U.S.-Russian relations during President Obama’s first term was graphically described by Andrew Kuchins, a leading U.S. expert on Russia at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, who noted that the Obama Administration’s ‘reset’ strategy in relations with Russia should be interpreted as a policy “to try to strengthen Medvedev’s domestic political standing at home through foreign policy achievements with the United States.” [4].

He was therefore correct in giving the exact date when this ‘reset’ ended: September 24, 2011, “when at the United Russia Party Congress it was revealed that Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev, the so-called tandem, would switch places, with Putin again becoming president of Russia. It was at this time that U.S.-Russia relations took a decided turn for the worse with the first of Russia’s double vetoes (with China) on UN sanctions on Syria in early October. Kremlin criticism of the United States multiplied and became much sharper as the fall progressed on issues including Syria, missile defense, Iran, and others.” [5]

Quite naturally, the pain suffered by the Obama Administration on the political chessboard when it lost the game of “playing on differences in the tandem” could not but tell on the gradual transformation of expert assessments into stereotypes in the U.S. public mind. Apparently prompted by the U.S. Administration at the start of Barack Obama’s second term in office, a campaign was launched in the U.S. mass media to “demonize” the image of President Vladimir Putin. In early 2013 a publication by researchers Hill and Gaddy at the Brookings Institution (a think tank rumored to be close to the U.S. political leadership) entitled ‘Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin’ sparked widespread debate [6]. As a result, although during President Putin’s first term (2002-2003) U.S. public opinion about his image and work was split approximately 40 to 25 percent in his favor, at the start of his third term only 19 percent of respondents had anything positive to say about him, against 54 percent who were negative [7].

Obviously, given the politically charged domestic setting, it has been fairly hard to cultivate a sustainable and mutually beneficial bilateral relationship. All the more so since public opinion, open to manipulation, has acquired a certain autonomy and grown into a factor that U.S. politicians cannot afford to ignore while developing their domestic and foreign policies.

U.S.-Russian Relations: Skeletons in the Closet

The current stage of US-Russian relations involves the revival of some of the old forms of pressure used against the USSR, something the older generations remember only too well.

President Jimmy Carter’s time in office (1977-1981) is well remembered for its focus on human rights, which became virtually central to Washington-Moscow relations. It definitely had a domestic political dimension, because it was comprehensible to “common folk” on both sides of the Atlantic, in stark contrast to issues such as arms race limitation, which are understood only by a narrow community of highly-educated professionals. Washington’s official records clearly show that today the human rights topic prevails over any other issue in the U.S.-Russia relationship. The Congressional Research Service’s extensive report on political, economic and military issues in Russian and U.S. interests gives human rights top priority in the list of political issues in Russian society, while strategic arms limitation, including missile defense, is listed almost last [8]. The author counted 67 entries in the U.S. Department of State’s official records under the header “Human Rights in Russia in 2013”.

To paraphrase, during 2013 the U.S. Department of State made pronouncements on human rights issues in Russia at a rate of 5-6 times a month, covering topics ranging from sexual minorities’ rights to anniversaries of various tragic events in Russia, e.g., the seventh anniversary of Anna Politkovskaya’s death [9].

Clearly, this aspect of how the U.S. foreign policy agency operates is strictly intended for domestic purposes, chiefly to produce a negative image of Russia in the U.S. public’s consciousness. The United States must be aware that while human rights issues are daily fare for the U.S. they are extremely painful for Russia, paralyzing the political will to normalize the relationship and promote cooperation. In sociological terms, this superstructure acts like a tail, “wagging” the basis of our relationship.

During the Cold War, the ideological confrontation between the United States and the USSR reached its apogee, and many episodes all but became classics, such as the legendary “kitchen debates” between U.S. Vice President Richard Nixon and Nikita Khrushchev in fall 1959, during the U.S. commercial exhibition in Moscow, or the ideological “tit-for-tat” at the meetings between John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev on June 3-4, 1961 in Vienna, Austria. It looks as if these days the tradition may be making a comeback, and at a level that no old cold war spin doctor could have imagined in their wildest dreams.

At the end of his article in the New York Times on September 12, 2013, which caused such a buzz in the United States, Russian President Vladimir Putin disagrees with the case made by the U.S. President “…on American exceptionalism, stating that the United States’ policy is “what makes America different. It’s what makes us exceptional.” It is extremely dangerous to encourage people to see themselves as exceptional, whatever the motivation.” [10].

These words caused a veritable storm in the U.S. mass media. Numerous commentators ranted about the mere fact that the Russian leader was given space in the newspaper at all, and the New York Times’ editors were forced to explain themselves [11].

U.S. public opinion demanded that Barack Obama come up with an “adequate” ideological response. Addressing the United Nations General Assembly on September 24, 2013, during his lengthy speech, the U.S. President said: “The danger for the world is that the United States, after a decade of war -- rightly concerned about issues back home, aware of the hostility that our engagement in the region has engendered throughout the Muslim world -- may disengage, creating a vacuum of leadership that no other nation is ready to fill.” [12]

As the history of conceptual confrontation between the USSR and the United States late in the 20th century shows, ideological polemics between the two countries’ political leaders often served as a prelude to grave international crises, such as the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

The Cold War grew out of the superpowers’ desire to change the global geopolitical reality by transforming how their spheres of influence were configured. Today, with the rapid globalization of economic links, the United States and Russia both face growing competition from other countries on the world’s markets for goods, services and workforce. Suffice it to say that in 2012 the European Union (EU) had already outstripped the United States in gross domestic product (GDP) terms, as total EU GDP reached USD 16.67 trillion [13] compared to U.S. GDP of USD 16.25 trillion [14]. Close on U.S. heels is China, taking second place in 2012 global economic rankings, and boasting a GDP of USD 8.36 trillion, just half that of the United States [15] Geo-economy is gradually replacing geopolitics.

Under the circumstances, unwavering attempts to superimpose old-fashioned geopolitical templates on this new geo-economic reality have morphed into yet another factor prompting a tangible decline in relations between the two countries. As the global economy is becoming increasingly competitive, the U.S. ruling elite has reacted badly to the emerging Eurasian Union, seeing it as a threat to its geopolitical interests.

This trend was highlighted by one of the Heritage Foundation’s leading experts on Russia, Ariel Cohen, who recently described the Eurasian Union as a “new authoritarian, anti-Western, mercantilist Russian sphere of influence would recreate the dynamics of the 19th century Great Game between the Romanov Empire and the British Empire and of the 20th century Cold War.” [16]

The United States is losing its leadership in the world economy, and its weak recovery after the 2007–2009 financial and economic crisis adds to the important, and probably the most controversial, factors responsible for worsening relations between the United States and Russia. One could well conclude today that while Barack Obama remains in office, i.e. through January 2017, the status of U.S.-Russian relations will continue to worsen, and the domestic situation in the United States will significantly contribute to this process, while the U.S. political elite tries to reap additional political dividends from the U.S. public’s changing sentiments towards Russia and its political leadership.

1. U.S. Department of State. Fourth Anniversary of Magnitskiy's Death. Press Statement. Jen Psaki, Department Spokesperson. Washington, November 15, 2013 // http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2013/11/217649.htm.

2. Swift A. For First Time, Americans' Views of Russia Turn Negative Despite approval of Russian plan for Syria, Americans sour on Putin. September 18, 2013. − http://www.gallup.com/poll/164438/first-time-americans-views-russia-turn-negative.aspx.

3. Pew Research Center. Global Opinion on Russia Mixed. September 3, 2013. PP. 2,3. − http://www.pewglobal.org/files/2013/09/Pew-Global-Attitudes-Project-Russia-Report-FINAL-September-3-20131.pdf

4. Center for Strategic & International Studies. Critical Questions for 2013: Regional Issues. Russia in 2013.Andrew C. Kuchins, Senior Fellow and Director, Russia and Eurasia Program. January 25, 2013. − http://csis.org/publication/critical-questions-2013-regional-issues.

5. Ibid.

6. Hill F., Gaddy C. Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin. Washington, The Brookings Institution, 2013, XII + 390 pp.

7. Swift A. For First Time, Americans' Views of Russia Turn Negative Despite approval of Russian plan for Syria, Americans sour on Putin. September 18, 2013. − http://www.gallup.com/poll/164438/first-time-americans-views-russia-turn-negative.aspx.

8. CRS Report for Congress. Russian Political, Economic, and Security Issues and U.S. Interests. September 13, 2013. RL33407. PP. 2-20; 68-80.

9. U.S. Department of State. Human Rights in Russia: 2013. − http://www.state.gov/p/eur/ci/rs/c57474.htm.

10. The New York Times. September 11, 2013. A Plea for Caution From Russia. By VLADIMIR V. PUTIN. − http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/12/opinion/putin-plea-for-caution-from-russia-on-syria.html?_r=0&pagewanted=print; President of Russia. Syria’s Alternative. 12 September 2013. Article by Vladimir Putin published in the New York Times (in Russian). − http://kremlin.ru/news/19205http://kremlin.ru/news/19205.

11. The Public Editor's Journal - Margaret Sullivan. September 12, 2013. The Story Behind the Putin Op-Ed Article in The Times. − http://publiceditor.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/09/12/the-story-behind-the-putin-op-ed-article-in-the-time.

12. The White House. Office of the Press Secretary. Remarks by President Obama in Address to the United Nations General Assembly. September 24, 2013. − http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/09/24/remarks-president-obama-address-united-nations-general-assembly.

13. IMF. Report for Selected Country Groups and Subjects. World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013. − http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=33&pr.y=11&sy=2012&ey=2012&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=001%2C998&s=NGDPD&grp=1&a=1.

14. United Nations Statistics Division. National Accounts. − http://unstats.un.org/unsd/snaama/dnltransfer.asp?fID=2.

15. Ibid.

16. Cohen A. Russia’s Eurasian Union Could Endanger the Neighborhood and U.S. Interests. – «Backgrounder», No. 2804. June 14, 2013, p. 10.− http://report.heritage.org/bg2804.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |