The Structure of Energy Politics in the South Caucasus: Grounds for Consolidation or Cooperation?

Oil derricks, Baku, Azerbaijan

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

South Caucasus has the potential of becoming a stumbling block for both the EU and the EEU in terms of energy cooperation. For now the region remains on the bottom of priority list for both Europe and EEU countries, but in the future when the latter finalize their common energy policy, the South Caucasus may face intense competition from both neighbors. Still the remaining obstacles both within the region and outside of it create too many unresolved issues, which in turn hinder the smooth development of cooperation.

South Caucasus has the potential of becoming a stumbling block for both the EU and the EEU in terms of energy cooperation. For now the region remains on the bottom of priority list for both Europe and EEU countries, but in the future when the latter finalize their common energy policy, the South Caucasus may face intense competition from both neighbors. Still the remaining obstacles both within the region and outside of it create too many unresolved issues, which in turn hinder the smooth development of cooperation.

The European Union (EU) and the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) are in the process of elaborating common energy security policies. The Europeans are significantly ahead in this field and have already started the creation of common energy market that is protected from foreign expansion.

It is inevitable that Russia and the EU will continue developing their strategic partnership on energy security cooperation. The need for this is dictated by the interdependence of the Russian and European economies on fuel imports and exports. However, the EU regards the South Caucasus region (and Azerbaijan, in particular) as a potential energy supplier along with Russia in terms of diversifying its energy resources.

At the same time Russia and the European Union are trying to limit each other’s influence in the energy sector. Europe has adopted a complex of measures called the Third Energy Package aimed at defending its domestic market from foreign influence, as well as sanctions against the Russian energy sector. Conversely, Russia is shifting away from the EU in favor of enlarging the Asian market share of developing countries.

Russia and the EU look at the South Caucasus region differently. Russia does not consider it important in terms of its energy security policy. The South Caucasus’s share of Russia’s exports is extremely small and Russia does not use this regional infrastructural system to deliver its oil and gas to European consumers.

Common Energy policy of the Eurasian Economic Union

Ivan Timofeev, Elena Alekseenkova:

Eurasia in Russian Foreign Policy: Interests,

Opportunities and Constraints

The EEU has barely begun elaborating a security policy – a process that could be long and complicated. Member states expect the first results of the common policy in creating a common electricity market by 2019 (and a common oil and gas market by 2025). Until then Russia will remain the main negotiating party of the EU in energy security. EEU leaders will need to take into the account the interests of three major groups of countries: importing countries (Armenia, Belorussia and Kyrgyzstan), exporting countries (Kazakhstan and Russia) and transit countries (Belorussia).

The energy security of the importing countries of the EEU consists of “the uninterrupted availability of energy sources at an affordable price.” [1] Exporting countries pay more attention to the “security of demand”; the sustainable demand for hydrocarbons for reasonable prices on the international markets [2].

In the case of the EEU leaders – Russia and Kazakhstan [3] – the export of hydrocarbons is one of the largest income items in the structure of their national budgets. Russia’s export of hydrocarbons abroad declined to 66,4% of total exports in 2015 (in comparison with 73,4% in 2014). The export structure to the countries of Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS countries) differs, but the major part still belongs to hydrocarbons (39,5% in 2015 and 43,6% in 2014) [4]. The share of oil and gas sector in federal budget income was 42% in 2015 (5,862 bn ₽ out of 13,655 bn ₽) [5].

Hydrocarbons play even greater role in the export structure of Kazakhstan than in Russia. According to the data from the National agency on export and investments “Kaznex Invest,” the share of primary resources in Kazakhstan exports amounted to 78% in 2014 [6]. The share of oil and gas sector in federal budget income was 44% in 2014 [7].

Transit countries (such as Belarus) play no lesser role in the concept of energy security. Their energy security policy has to take into account the interests of importing and exporting actors - the availability of energy sources, affordable pricing, and the security of demand.

Currently the common energy policy of the EEU exists as a series of main principles that will lay the ground for coordinated work within a future common energy space. The principles shared by all the members of the EEU (Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia), are aimed at building a common energy policy as well as a common energy space. The principles include:

- Regulating market pricing for energy resources;

- Ensuring the development of competition in the common markets of energy resources;

- The removal of technical, administrative and other barriers to trade in energy resources, equipment, technology and related services;

- Ensuring the development of a transport infrastructure for the common markets of energy resources;

- Ensuring non-discriminatory conditions for economic entities of the Member States in the common markets of energy resources;

- Creating favorable conditions for attracting investments in the energy sector of the Member States;

- Harmonizing national rules and regulations for the proper functioning of the process and business infrastructure of the common markets for energy resources [8].

These principles will help the EEU create conditions for gradually establishing a common energy market (including gas, oil and petroleum products) by 2025 [9]. Before that Russia is likely to preserve its leading role in the negotiation process with the EU in terms of energy cooperation.

Russia-EU Interdependence

The EU relies heavily on fuel imports, importing 53% of the energy it consumes: crude oil (almost 90%), natural gas (66%), and to a lesser extent solid fuels (42%) as well as nuclear fuel (40%) [10]. The share of Russia in the European energy sector is significant - it is Europe’s biggest importer of oil (35%), gas (26%), coal (30%), and uranium (25%) [11].

Due to many reasons – especially political tensions– the energy policy of the European Union is aimed at a gradual diversification of fuel imports, primarily diminishing oil and gas exports from Russia. Official EU documents develop the idea more closely, indicating that Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Iraq and Iran could appear to scale down the dominant position of Russia [12]. The logic of diversification is supported by the EU’s aspiration to change the European market rules in terms of distribution and transportation of natural gas. The European Union has already limited the possibilities of Russian exports by adopting the Third Energy Security Package (in particular, “Gazprom” had to give up the “South Stream” pipeline and “Nord Stream” could be used only at half of its capacity [13] ).

Western sanctions imposed on Russia in 2014 pushed European and American energy companies out of joint oil projects. For example, “ExxonMobil” stopped exploiting two rigs, “Universitetskaya-1” and “Tuapse Trough”; “Total” was forced to leave one of the Western Siberia rigs. All the projects have been frozen as Russian companies (Rosneft and Lukoil, respectively) do not have the technology and experience to exploit them alone.

According to the Russian governmental report, Western sanctions have not influenced the exploitation or export of natural resources [14]. Up until today Russia mostly exploits open-access oil resources. In 10-20 years, they will be replaced by isolated oil and Russia may face decline in oil production and export. To overcome these possible difficulties, the government needs to stimulate import substitution in oil and gas engineering, energy engineering, petroleum chemistry and crude oil refining. As a result, the sanctions imposed by Western countries have narrowed the window of cooperation possibilities between Russia and the EU in energy security.

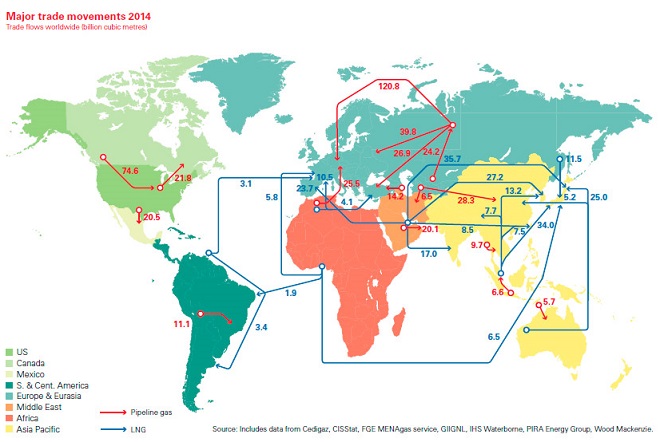

Major trade movements of natural gas in 2014 [15]

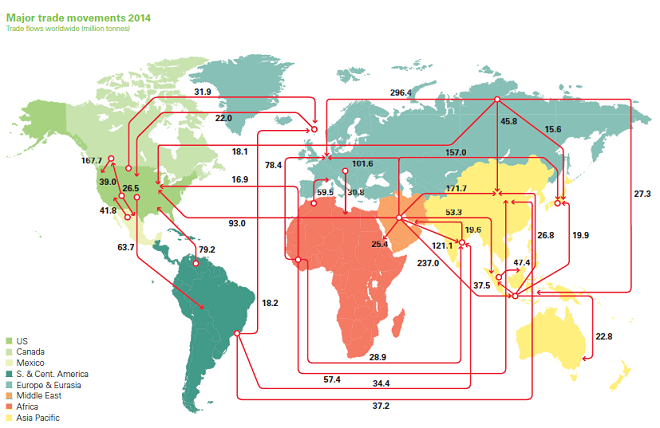

Major trade movements of oil in 2014 [16]

Taking into account the resource-driven component of the economy Russian government plans to allocate fuel money to social and economic development. According to the “Energy Strategy of Russia until 2035” – the principal document that outlines Russia’s strategy and actions in the sphere of energy – Russia’s main aim consists in “a structural shift of the energy park of the Russian Federation to a high, qualitatively new level that will boost the country in its dynamic social and economic development.” [17]

The challenges that Russia faces in realizing its energy policy are the following:

- Low global oil prices and their volatility;

- Stabilization or even reduction of the growth rate of foreign demand;

- Rising extraction costs of hydrocarbons;

- Sanctions and other restrictions on technology exports to Russia.

“Reduction of the growth rate on foreign demand” is a challenge that presumes that the Russian share in the European energy sector will remain at the same level or gradually diminish because of these main factors:

- The EU diversification policy;

- Competition with new oil and gas suppliers (mainly from the US, Iraq, Iran and East Africa);

- Political tensions with the European countries;

- A more energy efficient and ecologically friendly EU economy.

To overcome existing and future challenges Russia has started shifting its energy focus towards enlarging the Asian (first of all, Chinese) market share of developing countries; the “Energy Strategy of Russia until 2035” requires “to change the production and transportation energy complex taking into account the development of Russian East as well the diversification of hydrocarbons export to the Asia-Pacific Region.” [18]

The need for diversification is common to both the European Union and Russia. While the European Union aspires to diminish the role of Russian imports, Russia wants to be sure that new Asian markets will provide its economic and social development with sufficient amounts of fuel. Both actors are highly dependent on energy resources and put energy security priorities on top of the agenda. Although the EU and Russia are highly interdependent in terms of energy supply, both actors have already started to drift apart from each other as they adjust to internal and external circumstances.

Narrowed Ways of Cooperation in the South Caucasus

Sophia Kortunova:

When You Just Can’t Say “Yes”. Are Oil Prices

Likely to Go Up?

Despite heavy interdependence between EU and Russia, the region of the South Caucasus does not offer many ways of energy cooperation between two blocs. This is explained by two main factors: economic imprudence and geopolitical risks.

Economic imprudence

The “Energy Strategy of Russia until 2035” does not mention the South Caucasus region. This fact vividly proves that the Russian Federation does not consider the region as a) a threat to national energy security or b) a possible vehicle for mutual cooperation between Russia and regional actors.

The absence of the threat to Russian energy security is explained by the incommensurability of production and export volumes. Azerbaijan – the only regional country exporting energy resources – cannot compete with Russia alone. In 2014 Russia produced 534 million tons of crude oil, which is 12 times more than Azerbaijan (42 million tons). At the same time the country consumed 148 million tons (compared to 4,6 million tones in Azerbaijan). Export of Russian crude oil exceeded that from Azerbaijan by more than 10 times over [19].

The situation with regards to natural gas is the same. In 2014, the production of natural gas by Russia was 34 times greater than that of Azerbaijan (578 bcm and 17 bcm respectively), natural gas consumption is more than 40 times higher (409 bcm and 9 bcm respectively), and exports are more than 24 times greater (187 bcm and 7,7 bcm respectively) [20]. Moreover, in 2014 only 0,2 bcm of Azeri gas was transported via the Russian pipeline system [21].

In 2014 European Union was a major consumer of Azeri natural gas and oil, thus making Russia and Azerbaijan competing parties. However, the incommensurable volumes of production and export between the two countries cannot make Russia see Azerbaijan as a potential opponent at the European market.

The South Caucasus region cannot be regarded as a vital oil and gas market for the Russian Federation. Currently Russia provides only its strategic partner with energy – Armenia, while Georgia is partly dependent on Azeri exports, and Azerbaijan is self-sufficient. Even if Georgia decides to reject Azeri exports in favor of Russia, the region will not account for any vital part of the Russian export ratio.

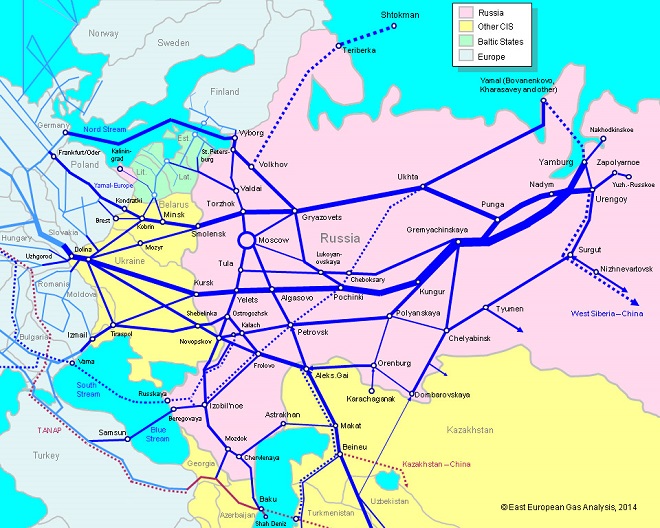

Russia does not export its natural resources to Europe or Turkey (its two most important natural gas importers) via the territory of the South Caucasus region. For fuel transportation, Russia mostly relies on the pipeline system of Ukraine and Belorussia, or uses pipelines that do not cross other countries (Nord Stream, Blue Stream, Nord Stream 2) [22]. There are no plans for building new pipelines via the South Caucasus. Therefore, the region does not have any influence on the transit security and reliability of Russian fuel exports.

Major Gas Pipelines of the Former Soviet Union [23]

The major threat to the Russian energy security policy consists in declining revenues from exporting natural gas and oil to the European Union. In the case of the South Caucasus, the threat does not come from Azerbaijan (as the country alone cannot compete with Russia on production and export of natural resources), but from potential suppliers in Asia (Turkmenistan in particular) and Middle East (Iraq and Iran). The EU considers the Southern Corridor and other similar projects (TAP, TANAP) as “an important element” that “sets the ground for supplies from the Caspian region and beyond” [24].

Long-term projects do not have any fundamental basis and remain only on paper. At the moment the legal status of the Caspian Sea bed remains unresolved. On the one hand, the EU is making efforts to facilitate the process, while Russia is trying to slow it down as it does not correspond with the country’s interests in the sphere of energy security (potential gas suppliers from Central Asia and Middle East could diminish the role of Russia on the European market and cut revenues from fuel energy). On the other hand, the prices for oil and gas have fallen recently, making it practically meaningless for the countries to spend enormous amounts of money on low-performing assets.

Geopolitical risks

Cooperation between the EU and the EEU in South Caucasus faces many geopolitical challenges and obstacles.

Firstly, the region of the South Caucasus remains very unstable because of two frozen conflicts and territorial disputes. The conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan has seen an escalation over the last year: in 2015 clashes on borders claimed the lives of 90 Azeri soldiers [25]. Both parties violated the existing ceasefire and used heavy weapons for the first time since 1994 when the ceasefire treaty was signed. During the night of April 1, 2016, clashes erupted between Azerbaijan and Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh, leading to a four-day operation resulting in significant losses on both sides.

Relations between Georgia, on the one hand, and Abkhazia and South Ossetia, on the other hand, seem to be more stable because of the Russian protectorate over two partly-recognized states. Nevertheless, experts still remember the 2008 war and events that preceded the conflict. On August 6, 2008, near the eastern Turkish city of Erzincan the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline exploded. Anonymous hackers “shut down alarms, cut off communications and super-pressurized the crude oil in the line” which led to the blast [26]. US intelligence agencies believe the Russian government was behind the Refahiye explosion. Moreover, a few days later, after the beginning of 5-day August war between Russia and Georgia, Georgian Prime Minister Nika Gilauri accused Russia bombing the BTC pipeline near the city of Rustavi. Luckily the bombs missed and the pipeline did not suffer any damage. The events of the last two decades show that the situation in the region can get out of the control in a very short period of time. Unfortunately, the security of pipeline infrastructure and the sustainable transit of hydrocarbons are questionable.

US intelligence agencies believe the Russian government was behind the Refahiye explosion. Moreover, a few days later, after the beginning of 5-day August war between Russia and Georgia, Georgian Prime Minister Nika Gilauri accused Russia bombing the BTC pipeline near the city of Rustavi. Luckily the bombs missed and the pipeline did not suffer any damage.

Secondly, countries cannot merge their national interests regarding energy issues in the region due to the numerous political disagreements and deadlocks. Armenia has made its choice and became a full-fledged member of the EEU in 2015. That means that the country will coordinate its energy policy with the members of the organization and first of all Russia. Russia dominates in the Armenian gas and energy sector. “Gazprom Armenia”, the leading company in transit and sale of natural gas in Armenia, is a wholly-owned subsidiary of “Gazprom.” [27] At the same time the distribution of electric power is under the control of “Electric networks of Armenia”, a company that fully belongs to Russian “Inter Raoues.” [28] The strategic cooperation with Russia and the very complicated relationship with Azerbaijan and Turkey leave very little room for future fruitful cooperation with the EU.

Georgia presents itself as a transit country. The country is heavily interested in sustainable and trouble-free transit of hydrocarbons as it receives money or resources as payment. Nevertheless, Georgia has difficult relationships with Russia. The recognition of the independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia has forced Georgia to break off diplomatic relations with Russia. Despite recent positive events in restoring cooperation between the two countries – for example access of Georgian goods on the Russian market, the re-initiation of regular flights between the two countries, progress on the question of visas for Georgians – Russia continues to treat Georgia as one of the main geopolitical threats to its national interests in the South Caucasus. To a large extent it is explained by the aspiration of Georgia to join NATO and the EU, which contradict the security interests of Russia. As a result, full-scale cooperation between Russia and Georgia (or Russia and EU involving Georgia) on possible and perspective energy projects seems hardly feasible in current circumstances.

Thirdly, different and contradictory interests of foreign countries clash in the South Caucasus. Despite the ending of operation in Syria, Russia and Turkey maintain aggressive rhetoric and disagreements. The Russian jet shot down by Turkish warplanes put on hold the realization of the joint energy project “Turkish Stream”, jeopardized the 10% discount for Russian gas and made negotiations over future exports even more complicated.

Moreover, Russia is interested in reducing the number of potential alternative energy projects aimed at supplying Europe with energy resources. The country seeks to remain the major supplier of the EU and is ready to defend its interests in the region within the limits of international law.

Possible Scenarios

Cooperation between the EU and the EEU can go in three different ways: positive, negative and neutral.

The positive scenario assumes that the EU and the EEU will steadily move towards creation of a common energy space (including the South Caucasus). Both integration blocs will have a sufficient level of trust to start the process of national legal harmonization in favor of creating common oil and gas markets.

Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia will have to take necessary steps as well to join the common energy market. Armenia will take up the obligations of the EEU that will have more political force in favor of national legislation. Georgia will have to accept new rules of the game following its path towards EU membership. Both blocs will have to exercise political influence on Azerbaijan (and Turkey) to make them join the common energy space and accept common regulations.

However, this scenario seems unlikely because of the existing political tensions between the members of two blocs, regional conflicts and economic imprudence.

Under a negative scenario there is no space for cooperation between the two blocs. Both the EU and the EEU will vigorously defend their interests in the sphere of energy security, avoiding any chance for mutually beneficial cooperation. The scenario depends on the level of political conflict between the EU and the EEU, and Russia especially.

Here circumstances as well as regional conflicts and their prevention move to the forefront. It is extremely important to create or renew the existing mechanisms of control over the frozen conflicts. The aggravation of tensions (first of all between Armenia and Azerbaijan), as we have seen over the weekend of 1-4 April 2016, may put the situation out of control. Therefore, regional security issues dominate energy cooperation efforts.

If the EU and the EEU avoid further political escalation, then a neutral scenario seems to be highly probable. The scenario assumes that the parties will take into account and respect the interests of each other in planning their energy strategies. Cooperation will stay at the same level; the blocs will not be able to overcome the existing tensions but there will be no escalation of political confrontation.

In the South Caucasus, Russia would not oppose Azeri exports to Turkey and the EU. At the same time, it will not turn a blind eye to the efforts of building transit infrastructure via the region. Russia will defend its interests according to international law, but EU determination will hardly promote mutual cooperation. Therefore, it will be more efficient for the EU to focus on African and US energy export, than trying to finish a new infrastructure project via the South Caucasus region.

Appendix [29]

Russia’s Energy Park

Russia preserves its leading role in extraction and exportation of hydrocarbons. The structure of its energy park is based on three main resources:

- Oil. In 2014 Russia ranked 6th in proven oil reserves with 14,1 billion tons or 6,1% of the global share. The country produced 10 838 thousand barrels daily (2nd place after Saudi Arabia) and 534,1 million tons in 2014 (12,7% of the total share).

- Natural Gas. In 2014 Russia ranked 2nd (after Iran) in proven natural gas reserves with 32,6 trillion mі or 17,4% of the global share. The country produced 578,7 billion mі or 16,7% of the total share.

- Coal. In 2014 Russia ranked 2nd in proven coal reserves with 157 010 million tons or 17,6% of the global share. The country produced 170,9 million tons oil equivalent or 4,3% of the total share.

Kazakhstan’s Energy Park

Kazakhstan occupies 2nd place among CIS countries;

- Oil. In 2014 Kazakhstan ranked 11th in proven oil reserves with 3,9 thousand million tons or 1,8% of the global share. The country produced 1 701 thousand barrels daily and 80,8 million tons of oil in 2014 (1,9% of the total share).

- Natural Gas. In 2014 Kazakhstan’s proven reserves of natural gas were estimated at 1,5 trillion m 3 or 0,8% of global share of proved natural gas reserves. The country produced 19,3 billion m3 or 0,6% of total share.

- Coal. In 2014 Kazakhstan proven coal reserves were estimated at 33 600 million tons or 3,8% of the global share. The country produced 55,3 million tons oil equivalent or 1,4% of the total share.

| Pipeline | Capacity | Destination of exports |

|---|---|---|

| Via Ukraine: | ||

| Orenburg-Western border (Uzhgorod) | 26 | Slovakia, Czech, Austria, Germany, France, Switzerland, Slovenia, Italy |

| Urengoy-Uzhgorod | 28 | Slovakia, Czech, Austria, Germany, France, Switzerland, Slovenia, Italy |

| Yamburg-Western border (Uzhgorod) | 26 | Slovakia, Czech, Austria, Germany, France, Switzerland, Slovenia, Italy |

| Dolina-Uzhgorod - 2 lines | 17 | Slovakia, Czech, Austria, Germany, France, Switzerland, Slovenia, Italy |

| Komarno-Drozdowichi - 2 lines | 5 | Poland |

| Uzhgorod-Beregovo - 2 lines | 13 | Hungary, Serbia, Bosnia |

| Hust - Satu-Mare | 2 | Romania |

| Ananyev-Tiraspol'-Izmail & Shebelinka-Izmail - 3 lines | 26 | Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, Macedonia |

| Total via Ukraine: | 142 | |

| Via Belarus: | ||

| Yamal-Europe (Torzhok-Kondratki-Frankfurt/Oder) | 33 | Poland, Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, UK |

| Kobrin-Brest | 5 | Poland |

| Total via Belarus: | 38 | |

| St. Petersburg-Finland - 2 lines | 6 | Finland |

| Blue Stream (design capacity) | 16 | Turkey (possible to Greece, Macedonia) |

| Nord Stream (design capacity) | 55 | Germany, France, Czech and other |

| TOTAL EXISTING EXPORT CAPACITY: | 257 | |

| Other New Projects: | ||

| Nord Stream- 2 | 55 | Germany, France, Czech, UK and other |

| Yamal-Europe-2 | 15 | Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and other |

| Sub-total new capacity: | 133 | |

| TOTAL PLANNED EXPORT CAPACITY: | 390 | |

| Guaranteed contracted exports for 2020-2025 | 158 |

1. This definition of energy security has been proposed by the International Energy Agency (IEA) and deals with three main factors: reliability, accessibility and affordability. The IEA also pays attention to various time dimensions: “long-term energy security mainly deals with timely investments to supply energy in line with economic developments and sustainable environmental needs”, while “short-term energy security focuses on the ability of the energy system to react promptly to sudden changes within the supply-demand balance.”

International Energy Agency. 2015. Energy Supply Security 2014. https://www.iea.org/media/freepublications/security/EnergySupplySecurity2014_PART1.pdf, accessed on 30.03.2016. p.13.

2. The security of demand becomes crucial when revenues from exporting energy resources form a large part of governmental budget. In theory enormous profits guarantee stable economic growth and development, encouragement of investment and possibilities for further diversification and modernization of the energy sector.

3. More detailed information on Russian and Kazakh energy parks can be found in appendix.

4. Official Statistics of the Customs Service of the Russian Federation. http://eng.customs.ru/, accessed on 30.03.2016.

5. Ibid.

7. Analysis of Kazakhstan’s external trade in 2014. http://export.gov.kz/storage/ec/ec9701639de1f0a52c56ea8871e64f44.pdf, accessed on 30.03.2016.

7. Adyasov, Inokentii: Commonwealth at low oil prices. In: News Kazakhstan. 08.12.2014. http://newskaz.ru/comment/20141208/7307794.html, accessed on 30.03.2016.

8. Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Union. http://www.un.org/en/ga/sixth/70/docs/treaty_on_eeu.pdf, accessed on 30.03.2016, article 79.

9. The EEU has started the creation of common energy market and coordinate transport policy. In: Eurasian Economic Union. http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/nae/news/Pages/12-03-2015.aspx, 12.03.2015.

10. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. (28.5.2014). http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014DC0330&from=EN, accessed on 30.03.2016.

11. Algirdas Saudargas: Report on European Energy Security Strategy (18.5.2015). http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//NONSGML+REPORT+A8-2015-0164+0+DOC+PDF+V0//EN, accessed on 30.03.2016.

12. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. (28.5.2014). http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014DC0330&from=EN, accessed on 30.03.2016.

13. Gazprom gave up on Nord Stream expansion. In: Vedomosti. https://www.vedomosti.ru/business/news/2015/01/28/gazprom-otkazalsya-ot-rasshireniya-severnyj-potok, 28.01.15. Accessed on 30.03.2016.

14. Sectoral Sanctions: one year after (August, 2015). http://ac.gov.ru/files/publication/a/6155.pdf, accessed on 30.03.2016.

15. BP Statistical Review of World Energy (June, 2015). https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/pdf/energy-economics/statistical-review-2015/bp-statistical-review-of-world-energy-2015-full-report.pdf, accessed on 30.03.2016.

16. BP Statistical Review of World Energy (June, 2015). https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/pdf/energy-economics/statistical-review-2015/bp-statistical-review-of-world-energy-2015-full-report.pdf, accessed on 30.03.2016.

17. Energy Strategy of Russia until 2035. http://www.energystrategy.ru/ab_ins/source/ES-2035_09_2015.pdf, accessed on 30.03.2016.

18. Ibid.

19. BP Statistical Review of World Energy (June, 2015). https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/pdf/energy-economics/statistical-review-2015/bp-statistical-review-of-world-energy-2015-full-report.pdf, accessed on 30.03.2016.

20. Statistics of “Gazprom” natural gas exports differ from British Petroleum data. (207 bcm export and 187 bcm export).

21. BP Statistical Review of World Energy (June, 2015). https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/pdf/energy-economics/statistical-review-2015/bp-statistical-review-of-world-energy-2015-full-report.pdf, accessed on 30.03.2016.

22. More information on outlet capacity of export pipelines at the FSU border can be found in the appendix.

23. East European Gas Analysis. http://www.eegas.com/fsu.htm, accessed on 30.03.2016.

24. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. (28.5.2014). http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014DC0330&from=EN, accessed on 30.03.2016.

25. Evseev, Vladimir: Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Minsk Process as a Path to Settlement. In: Russian International Affairs Council (8.02.2016). /inner/?id_4=7227#top-content. Accessed on 30.03.2016.

As for Armenia the official data on soldiers killed during the conflict differs, but the suggestion that the casualties of both sides matches, seems to be reasonable.

26. Robertson, Jordan; Riley, Michael: Mysterious ’08 Turkey Pipeline Blast Opened New Cyberwar. In: Bloomberg (10.12.2014). http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-12-10/mysterious-08-turkey-pipeline-blast-opened-new-cyberwar, accessed on 30.03.2016.

27. Gazprom Armenia. http://armenia.gazprom.ru/, accessed on 30.03.2016.

28. Electric Networks of Armenia. http://www.ena.am/AboutUs.aspx?id=2&lang=3, accessed on 30.03.2016.

29. Data is based on BP Statistical Review of World Energy (June 2015). https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/pdf/energy-economics/statistical-review-2015/bp-statistical-review-of-world-energy-2015-full-report.pdf, accessed on 30.03.2016.

30. Data is based on East European Gas Analysis. http://www.eegas.com/fsu.htm, accessed on 30.03.2016.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |