The New China in the Asia Pacific Region

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Center for South-East Asia, Australia and Oceania Studies, RAS Institute for Oriental Studies

The countries of the Asia Pacific Region are a focal point of international attention. The phenomenon that is their transformation from vassal states dependent on Western colonial powers to sovereign states independently exerting an influence on world developments has been achieved within a generation, creating an impression of exceptional progress and success. This fact has provided grounds for some experts to maintain that the locus of global activity is shifting to or has already moved from the Atlantic to the Pacific region, and that over time this process will become increasingly obvious. However, taking a non-linear approach, the Asia Pacific map and alignment of forces in the region may experience a dramatic change over the next few decades.

The countries of the Asia Pacific Region are a focal point of international attention. The phenomenon that is their transformation from vassal states dependent on Western colonial powers to sovereign states independently exerting an influence on world developments has been achieved within a generation, creating an impression of exceptional progress and success. This fact has provided grounds for some experts to maintain that the locus of global activity is shifting to or has already moved from the Atlantic to the Pacific region, and that over time this process will become increasingly obvious. However, taking a non-linear approach, the Asia Pacific map and alignment of forces in the region may experience a dramatic change over the next few decades.

Advocates of the “linear approach” visibly prevail among the more active course-predictors for the Asia-Pacific region. These authors still remain within the realm of existing realties, even in their most daring projections: based on the fundamental development factors identified, they attempt to extrapolate into the future based on current processes. They believe that since China has been growing ever stronger for almost 50 years, all the while its influence and power gathering momentum, these processes are bound to continue indefinitely. They argue that it is only to be expected that in time China will gain such power as to become a dominant force in South-East Asia and neighboring areas of the Pacific.

Apparently this reasoning is not totally devoid of logic. However, any forecasts concerning the future of the Asia-Pacific region and South-East Asia ought to be based on notions and ideas about one’s self, the world and society predominant in the minds of the people of the region. Applying this approach forces “fundamental factors” related to politics and economics to the periphery, while human beings with their ambitions and ideas, intellectual and creative leadership, the ability to generate new models of the universe and reality and assert them in the minds of people, come to the fore. It is this image of the world which will conquer the minds of millions, especially the educated class of Asian countries, which will shape the Asian universe in the 22nd century.

Turning Away from China

This approach makes it evident that our centennial prognosis will differ dramatically from the majority of similar projections for the region put forward by experts in the field. Having accepted the viewpoint that the evolution of the spiritual and conceptual context is the main driving force behind any change, we are able to argue that the role of increasing economic ties between Asian countries, specifically those of South-East Asia and China, should not be overstated. Likewise, it would be counterproductive to repeat the argument, which has previously proved faulty on numerous occasions, that “economics” is a decisive development factor, that only economic growth can serve as a basis for resolving the numerous tasks facing these countries in terms of mutual convergence and integration.

There is no point in denying the fact that the volume of trade between the People’s Republic of China and ASEAN countries is soaring, that thousands of people across the region are studying Chinese (although, incidentally, it should also be noted that hundreds of thousands study English). However, the difficulty in their further convergence lies in the fact that to neighboring states China no longer represents “a model to emulate” as it perhaps did in the Middle Ages. They do not trust the authorities in Beijing and are reluctant to get involved in any political agreements or alliances with China.

In terms of ideology, China is virtually nonexistent in South-East Asia, except for the less than appealing slogans parroted by the various waning communist parties of the region. Neither China itself nor its political structure and behavior is considered in earnest as a model to be followed by other countries in South-East Asia, or, for that matter, anywhere in Asia.

Instead, the idea of a Western-type democracy has implanted itself in the minds of the region’s more influential social groups as the optimum approach to managing social and governmental affairs. An autocratic one-party political setup, similar to China’s, is perceived as a regimented system limiting natural human rights. Asian elites, their commitment to religious and traditionalist ideas notwithstanding, intrinsically (that is, in terms of their spirit and lifestyle) rather gravitate to the Western paradigm. Over recent decades they have made this paradigm their own and there is no indication that they have any plans to abandon it in future.

Admittedly, a purely Western-type democracy is nowhere to be found in Asia, but in a broader sense, a democracy as a realization of the viable, legitimate rule of the people does exist, and its influence in the region constantly expanding. It was only recently that South Korea was held hostage by a series of alternating military dictatorships, while today it has adopted a representative democracy complete with multi-party political system. Moreover, the ASEAN Charter, put forward at the summit held in Cebu (January 2007) and subsequently ratified by all 10 member-countries, identifies democracy as the universal model of political organization to be attained by all Asia-Pacific states.

The New China

But it is not just in the South-East Asian countries that democracy is gaining an ever stronger foothold. The entire package of democracy, i.e. free elections, a multi-party political system, the separation of powers, the protection of human rights, and freedom of business to operate without administrative pressure, etc., has long been popular with a significant proportion of China’s educated classes. This is evidenced by the dazibao (wall newspapers) of the early 1980s, in which authors demanded political pluralism, freedom and democracy, and also by the events on Tiananmen Square, when similar demands were put forward, to name but two phenomena.

Against the background of an enduring one-party political system, this body for the enforcement of democratic principles remains the chief alternative to the existing power structure. Since the Internet and IT are slowly but surely implanting Western concepts and connotations into Chinese society, it can be assumed that in all likelihood pro-democracy changes in China are all but inevitable. The slightest economic hiccup, or internal conflict within the party or ruling elite will trigger a “Chinese Spring” - pushing the country ever closer to a new democratic order.

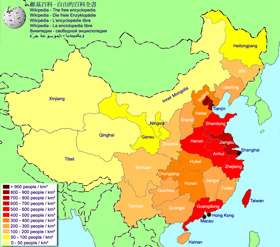

Under this scenario the People’s Republic of China would face the following problem: in all probability, with as democracy evolves, the country will gradually disintegrate into separate regions such as the prospering coastal South-West, the poverty-stricken traditionalist West, the industrial North-East, and the agrarian Center. It is quite possible that a national government will still be in place but that the real power will be exercised by the regional leaders, pursuing their own political course centered on their own key interests.

This scenario is quite realistic, reminiscent of events that took place in China in the 1920–1930s when, in the wake of pro-democratic reforms and due to a weakened central authority, the country de facto broke up into semi-independent and, at times, entirely independent parts headed by military cliques [1]. Indeed, on the one hand, given this profound mental drift, China’s transition to democracy is inevitable and will undoubtedly happen sooner or later but, on the other hand however, remains a high-risk course since the “Middle Country” may again disintegrate as it did in the 1920–1930s.

New-Old Alignment of Forces

Joint naval military exercises, United States and

the Philippines, June 2011

It can therefore be assumed that the geometry of power relations, and the broader balance of power in the region will undergo drastic changes. We, or rather our children, will witness a consolidation of pro-democracy, US-oriented countries, as well as the United States’ new role as a major driver of political and economic processes in the South-East Asian region as a whole and particularly – as regards China.

The United States’ return to South-East Asia is already apparent. Quite a few countries in the region not only welcome this process, but even urge Washington to take a more active stance on regional politics. The fact is that the ASEAN elites’ attempts over the 2000s to improve relations with China and move away from the United States bore no fruit. Ever-closer interaction with China only served to support and enhance their pre-existing suspicions over China’s ambition for dominance in the region.

The Philippines, which once rallied for American bases to be shut down and their troops to be pulled out, now demonstrate the most typical example of this new Pro-Americanism. As soon as China’s patrol vessels appeared near their coastline, the Philippines started to call for a renewal and extension of American military assistance. The agreement they had in mind was the Mutual Defense Assistance Act of 1951, previously the subject of severe criticism. Under this document the United States is bound to come to the rescue in the event of an attack on the Philippines.

In view of this fact, we can assume that the “hedge policy,” designed to curb China’s expansionism through neighboring countries allied with the United States, pursued by Republican and Democrat administrations alike, is to be continued. Its resilience and success are in large part due to the fact that its implementation does not require Americans to take an active or assertive role in their partners’ affairs. China’s Asian neighbors, not just the Philippines, fearing a dictate from Beijing, are eager to cooperate with the United States without being prompted. That is why the United States’ standing in the region, even though seriously weakened by the economic crises, will remain strong.

There is another possible scenario, under which the various separate parts of the disintegrating Chinese giant would likely integrate with adjacent countries. China’s neighbors are also prepared for this course of events, and would welcome it heartily. When I visited Japan, one of the leading professors at Hosei University said that he, like many Japanese intellectuals, believe that several civilizations existed in China existing simultaneously, one of them being identical to that of Japan. He called this a pelagic civilization and described the other as “continental.” He argued that the chief attribute of a pelagic civilization is the ability of its people to generate new ideas, be ready to change, be active and tolerant. He associated Taiwan, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Fujian, and most of coastal China with this definition. He argued that the agrarian provinces of China’s Center and West where, he argued, people have a more conservative mindset, are more suspicious of change and find it difficult to adjust to change, were part of this continental civilization.

If we accept this rationale, we may further assume that the victory of the democratic alternative will result in the emergence of several different loosely connected Chinas, exercising the same scope of freedom as modern day Taiwan. Individual parts of the former super-power, by then uncontrollable, will more likely than not become integrated into different geopolitical alliances. Xinjiang will become a dynamic player in Central Asia, successfully winning a dominant position there, not unlike Dzungaria, which was obliterated by the Chinese in the mid 18th century. Yunnan, Guangdong, Guangxi, essentially the whole of China’s South-West, together with the countries of South-East Asia, will form one of the most powerful and prosperous regional associations in the world. The integration of China’s North-East with Russia, Japan and the united Korea would produce no less impressive results. In a sense, China’s major regions could repeat the fate of the former USSR – where individual parts of a once super-power gained prominence in their own right and began integrating with neighboring states.

Several Russian companies, despite China’s

objections, have secured offshore oil and gas

exploration projects in the South China Sea

Russia’s role in the Asia-Pacific region and in South-East Asia has changed substantially over recent decades: from one of the main sponsors of the communist guerilla warfare in the 1950s, when the USSR in conjunction with the People’s Republic of China supported local communists, to a military-and-political partner and later a major ally of Vietnam in the 1970–1980s with one of the largest in the region military bases in Cam Ranh. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, Russia found its status reduced to that of a low-profile economic partner of the most important states in the region.

Under the best-case scenario for Russia’s future presence in the Asia-Pacific region, Russia would become a key regional hub thanks to a consistent, long-term, application of the Eastern-oriented policy that has already been launched successfully.

Russia’s regional influence would grow. The country would become a dynamic participant in political and economic associations of countries across the Asia-Pacific region, a process that will be further enhanced against the backdrop of China’s “democratic catastrophe.” Even now several Russian companies, despite China’s objections, have secured offshore oil and gas exploration projects in the South China Sea. Vietnam and other Asia-Pacific countries are importing a sizable proportion of Russian weaponry. In Vietnam Russia is leading a nuclear power station construction project, while a Russia-Vietnam free trade zone project is being discussed in Moscow. Russia is growing ever more self-confident and is making sure countries across Asia understand its free choice of political partners. In the spring of 2012, the Russian Fleet conducted the Yellow Sea joint naval exerciseinvolving Chinese vessels, and that summer Russia took part in fleet maneuvers with the United States, to which China was not invited.

The 22nd century will not see great confrontation between the world powers in the Asia-Pacific region. The era will be defined by quiet competition between Pro-American and Pro-Russian regional blocs, alongside joint efforts by the United States, Russia and countries in the region to promote security, free trade and prevent conflicts. Russia will likely develop close relationships with the united Korea and Vietnam, and the Northern and North-Eastern parts of China, while the United States will develop their contacts with Japan, the Philippines, Taiwan and South-West China. Indonesia will remain a key influence among the ASEAN states extending its clout to cover global issues.

* * *

The most popular technique used to generate scenarios for the Asia-Pacific region and South-East Asia involves extrapolating from current trends. However, in retrospect, it is clear that historical processes develop in a non-linear fashion, and cultural factors, such as views, behavioral patterns, ambitions and beliefs of people can drastically alter the course of history. Hence, the scenario that predicts a shift to democracy in China and which would also mean the breakup of the consolidated state into virtually independent polities should not be disregarded. This would be a major driver of change for the geopolitical geometry in the region. The policies adopted by the leading powers in the Asia-Pacific region will boil down to a benign competition between two rival blocs: Pro-American and Pro-Russian, while individual parts of the erstwhile “greater” China would be integrated into different geopolitical alliances.

1. For example, this happened in spring 1929 when Chiang Kai-shek’s troops (Jiang Gieshi), that is the forces of the Guomindang party, aspiring to the supreme power in China, fought the Guangxi clique whose influence covered the provinces of Guangxi, Guangdong, Hunan, and Hebei. Chiang Kai-shek was victorious, and the Guangxi clique’s influence shriveled to the Guangxi province. In May 1929, tensions arose between the Guomindang government and warlord Feng Yuxiang, whose army controlled the Northern provinces and was ready to occupy Shandong after the anticipated withdrawal of the Japanese troops.

In summer 1930 Yan Xishan, the governor of Shanxi, advanced against Chiang Kai-shek. His troops occupied Beiping, which was once again renamed Peking (Beijing) and he declared it China’s capital in opposition to Nanking (Nanjing) – the capital of the Guomindang government. If in addition to this internecine conflict we consider the all but independent “Northern warlords” under Zhang Zolin and the communists ruling over freed areas, there is no doubt that at that time China as a consolidated and centrally governed state did not exist.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |