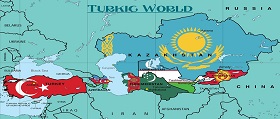

Russia and Turkey in Central Asia: Partnership or Rivalry?

Turkey's team riders parade before opening of

the first Asian Kokpar championship in Astana

September 11, 2013

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Dr. of Political Science, Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Problems of Transformation of Political Systems and Cultures, World Politics Department at Lomonosov Moscow State University

As they become more involved in the complex process of geopolitical balancing, the post-Soviet states of Central Asia are trying to shrink away from orienting on a single global or regional center in order to maintain smooth relations with all external actors represented in the region. Meanwhile, the situation there will largely be determined by the consequences of the withdrawal of the international coalition forces in Afghanistan. Military operations conducted by the coalition in Afghanistan since 2001 entered the final stage this year.

As they become more involved in the complex process of geopolitical balancing, the post-Soviet states of Central Asia are trying to shrink away from orienting on a single global or regional center in order to maintain smooth relations with all external actors represented in the region. Meanwhile, the situation there will largely be determined by the consequences of the withdrawal of the international coalition forces in Afghanistan. Military operations conducted by the coalition in Afghanistan since 2001 entered the final stage this year.

In light of this, the assessment of the security situation in Central Asia assumes a key importance. The challenges emanating from this region are particularly relevant for Russia, for which Central Asia is worth much in terms of both geopolitics and economics. On the other hand, an influential regional power such as Turkey is also interested in the development of economic, political and cultural cooperation with Russia and the Central Asian states, as well as maintaining stability in the region after the withdrawal of foreign troops from Afghanistan.

Afghan challenges in Central Asia

Although in the near-term outlook, the internal processes in Afghanistan, namely the struggle for power and inter-ethnic, inter-clan and inter-religious confrontations, appear to exert no direct and immediate impact on Central Asian states, their proximity to Afghanistan poses many problems for these countries. Indeed, should large-scale civil war resume in Afghanistan after 2014, hostilities may well spread into the territory of the Central Asian countries (Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan) bordering Afghanistan, and even more remote Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Ethnic Uzbeks and Tajiks from oppositional paramilitary units of Afghanistan and Pakistan (the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, etc.) now in the “gray zones”, that is inaccessible to government forces, can create serious problems as well.

The hypothetical prospect of the rise to power in Afghanistan of Islamist forces looks quite dangerous as well, for it could result in the radicalization of the Central Asian Ummah and growth in the activity of Islamist radical movements often associated with transnational terrorism organizations. Finally, the threats of intensified drug trafficking and drug production in Central Asia are very real, which both promote corruption and destabilize the internal political life of states.

External threats to political stability in Central Asia are being exacerbated by endogenous factors. The rapidly growing critical mass of internal problems in the region includes political and socio-economic instability, resulting from inter-ethnic and inter-clan tensions; confrontations among regional elites and clans; the impoverishment of the population and growing income and social disparities; corruption; and the low level of effectiveness of state structures.

The main security challenges emanating from Central Asia and associated with the external environment of Afghanistan and internal socio-economic and political problems are not of equal importance for Russia and Turkey. Russia considers drug trafficking, religious extremism, and the illegal movement of people and goods transiting through the region (especially from China), as the priority challenges emanating from Central Asia. For Turkey, a country which participated in the Afghanistan International Security Assistance Force, the priority is ensuring stability in Central Asia without creating threats to its economic and energy projects. At the official level, Turkey has emphasized the threat of radical Islam penetration into the Central Asian countries, although Turkey also faces this threat itself.

Russia and Turkey are trying to protect themselves and the region from existing and potential challenges and threats. They hope to stabilize the situation by developing economic, energy, road and transport projects as well as by intensifying the activity of regional security structures. Russian and Turkish involvement in these instances can help solve many security problems. The positive dynamics of bilateral Russian-Turkish relations and the conditions already at hand for a multi-aspect strategic partnership between Russia and Turkey favor such a development.

The main security challenges emanating from Central Asia and associated with the external environment of Afghanistan and internal socio-economic and political problems are not of equal importance for Russia and Turkey.

Russia is Turkey’s second largest foreign trade partner (32.7 billion dollars in 2013), and the latter ranks the eighth among the major foreign trade partners of Russia [1]. A favorable political and business climate creates successfully functioning institutions for interstate cooperation. As such, in May 2010, the High Level Cooperation Council was established, headed by the presidents of both countries, which held its fifth meeting on December 1, 2014 in Ankara and was attended by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

In terms of foreign policy, Russia and Turkey share the negative attitudes towards the activity extra-regional actors in Central Asia, South Caucasus, and the Black Sea region if the situation there is destabilized.

Turkey's relations with the countries of the region

Although Turkey demonstrates “an example of successful functioning of a secular political system with elements of Western-style democracy that managed to carry out market reforms in a society dominated by adherents of Islam” [2] to countries in Central Asia, its presence in the region is restrained by a lack of investment potential. The total volume of Turkish trade with Central Asian countries in 2010 amounted to 6.5 billion dollars, while Turkish investments reached $4.7 billion [3 ]. Since then the situation has changed little. Turkey also provides financial assistance to certain Central Asian states in the form of grants, loans and technical support.

The IV Summit of the Council was held in early

June 2014 in the Turkish port city of Bodrum.

The Summit resulted in signing of the

declaration “Turkic Council-Modern Silk Road.”

In 1992 the government created the Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA) to carry out economic and social programs aimed at poverty eradication and sustainable development in 30 partner countries, including those of Central Asia [4].

The Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States, which includes Azerbaijan, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan was established in 2010 in Istanbul. The IV Summit of the Council was held in early June 2014 in the Turkish port city of Bodrum and discussed, among other things, the possibility of transporting Caspian hydrocarbons to Europe [5].

The Summit resulted in signing of the declaration “Turkic Council-Modern Silk Road.” [6] This is one of the stages of implementing the “Silk Road” project that was launched in 2008 by the Ministry of Industry and Trade of Turkey and involves, among other countries, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. This project aims to link European markets with Asia, focusing on issues such as transport, security, logistics, and border customs procedures [7]. Despite Turkey's efforts to promote the development of economic cooperation with Central Asia, it cannot hold its ground with the economic influence of the far more powerful actors, namely China, US, EU, Russia and other countries that have their own interests in the region.

Without pining itself down to large-scale projects in Central Asia, Turkey prefers to promote – with the elements of so-called “soft power” – commercial, cultural and educational programs based on non-formal structures that are actively supported by the Turkish government. For example, at Nursultan Nazarbayev’s suggestion, the Parliamentary Assembly of Turkic-speaking Countries (TURKPA), the Council of Elders, and the World Assembly of Turkic Peoples, which deals with the study of the common historical roots of the Turkic culture, were all established in Central Asia.

Turkey has emphasized the threat of radical Islam penetration into the Central Asian countries, although Turkey also faces this threat itself.

The International Organization for the Joint Development of Turkic Culture and Art (TURKSOY) was established in 1993 in Almaty and the principles of its work are similar to those of UNESCO. However, TURKSOY does not confine its activity in Central Asia to culture and education alone, and deals with political, trade and economic problems facing the Turkic-speaking countries in the region [8]. However, in contrast to the official level (especially in Kazakhstan) that welcomes the activities of TURKSOY as well as other Turkish organizations, the penetration of Turkey not only in the cultural and economic, but also in the ideological, spheres of life in Central Asia evokes anxiety among representatives from civil society [9], who regard it as a threat of spreading the ideas of Pan-Turkism mixed with Islamism. This is seen as challenging the secular paradigm that has become well-established in all the Central Asian states.

Turkey's attempts to establish cooperation in the military-political sphere with the Central Asian states have come under notice as well. Therefore, in January 2013 in Baku, on the initiative of Turkey, TAKM – the Organization of the Eurasian Law Enforcement Agencies with Military Status was established (the abbreviation TAKM came from the names of the founding countries': Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, and Mongolia). In March 2014, Mongolia left the Organization, and its place was taken by Kazakhstan, which in 2016 will head the association [10] . The organization is aimed at promoting cooperation between its member states in combating organized crime, terrorism and smuggling activities, as well as the activities of radical groups. It emphasizes that comparing it with NATO or the OSCE is groundless due to the fact that unlike the latter, the association intends to act strictly within the territorial limits of the participating countries [11]. “The TAKM Association is not established against any country or organization” [12] and, as the Turkish media note, is not opposed to Russia, China or NATO [13].

Turkey enjoys the most advanced relations with

Kazakhstan, in cooperation with which it hopes

to form in the future a unified political and

economic space for all Turkic states

Turkey enjoys the most advanced relations with Kazakhstan, in cooperation with which it hopes to form in the future a unified political and economic space for all Turkic states (not only Central Asian) with a common market, a unified regional power grid, and an energy transportation system [14]. In a sense, this Turkic Project (as well as President Xi Jinping’s idea, put forward in September 2013, of including the Central Asian states in the Silk Road Economic Belt) challenges Russia's integration plans to create a Eurasian Economic Union. However, given the fact that the participating countries and the objectives of these projects overlap, they can complement each other and provide mutual assistance in developing a strategy for the Central Asian states’ response to internal and external challenges and risks.

Prerequisites for cooperation between Russia and Turkey in the region

The Central Asian region is of value to both Russia and Turkey. Here their cooperation has many opportunities due to a number of objective factors.

First, the advantageous geographical position of Turkey, which controls the Black Sea straits and plays the role of a bridge between Europe and Asia, opens new opportunities for Russia and the Central Asian countries to attain their own economic and political goals.

Second, Russia and Turkey, promoting their projects of regional cooperation and creating an atmosphere of trust and mutual interest of all participants in the integration process, help to reduce tensions in the region.

Third, Turkey and Russia as major Eurasian states with large Muslim populations can play the role of mediators in the relationship between the countries of Central Asia, the West and the Islamic world.

Fourth, the multi-vector policy pursued by all Central Asian states can be used by Russia and Turkey for promoting in-depth bilateral cooperation with the countries of the region.

Turkey and Russia are positively perceived in Central Asia due to their fairly neutral and rather restrained positions – in contrast to the “mentor” approach of the West – with respect to the internal political developments in the region.

Finally, Turkey and Russia are positively perceived in Central Asia due to their fairly neutral and rather restrained positions – in contrast to the “mentor” approach of the West – with respect to the internal political developments in the region (elections, human rights, democratic reforms, “color revolutions” and so forth).

The basis for Russian-Turkish cooperation with Central Asian states is the active rejection of radical Islamism. Both Russia and Turkey are interested in maintaining the secular nature of political systems in Central Asian states, which could contribute to eliminating potential instability in neighboring Afghanistan. Meanwhile, Russia is one of the few world powers that continues to promote the security of the Central Asian region, ensuring the safety of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan under the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and other structures, including the SCO.

The SCO, in which Turkey was granted the status of dialogue partner on April 26, 2013, seems to be the most promising format for Russian-Turkish cooperation (Russia is the chair of the SCO for one year starting from September 2014) in maintaining security in the region. Although the positions of Turkey and such major SCO member states as Russia and China on the Syrian issue have drifted apart, a regional organization of the caliber of SCO acquires a particular significance for Turkey amidst these new challenges. The underlying activity of SCO in combating “three evil forces,” namely terrorism, separatism, and extremism, can lay the foundation for cooperation between Russia and Turkey in Central Asia.

Areas of cooperation

Photo

Igor Ivanov:

Russia, Turkey and the Vision of Greater Europe

Started by Russia together with Belarus and Kazakhstan, projects to deepen economic integration within the Customs Union and the Eurasian Economic Community (EAEC), which Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Armenia plan to join in 2015, open new opportunities for Turkey to increase trade and economic contacts, as well as gain access to the markets of Siberia and China. Given the new profitable prospects offered by these associations, Turkey has expressed a readiness to discuss the possibility of creating a free trade zone between Turkey and the Customs Union with the participants of the emerging EAEC. This was announced by Russian Minister of Economic Development Alexei Ulyukayev after negotiations with his Turkish counterpart Nihat Zeybekçi in July 2014 [15]. The latter did not exclude the accession of Turkey, which is a member of the EU Customs Union, to the Eurasian Customs Union, although Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in his inaugural speech right after being elected President of Turkey on August 10, 2014 reiterated that “Turkey's path to the EU will continue.” [16]

There are a number of spheres that open up opportunities for Russian-Turkish interaction.

Firstly, cooperation can occur between the two countries within the framework of the emerging Eurasian integration (the Customs Union, the Eurasian Economic Union) due to relevant efforts by economic ministries and government agencies of the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan, which are interested in enhancing trade and economic relations with Turkey (energy, trade, and tourism).

Secondly, there is a possibility of energy projects with the participation of Russia, the Central Asian states-exporters (Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan), as well as Turkey as the largest Eurasian energy transit country.

Thirdly, there is room for cooperation between the military and diplomatic agencies of Russia and Turkey in the field of regional security. Since the main short-term problem appears to be the ability to meet potential threats from Afghanistan after the US and the International Security Assistance Force complete their mission there in 2014, the best way to address this problem would be within the SCO, which includes, along with Russia and the Central Asian states, Turkey and Afghanistan as well.

There are a number of spheres that open up opportunities for Russian-Turkish interaction.

Fourthly, combating crime, drug trafficking, and illegal movement of people, goods, weapons, etc. offer certain opportunities for cooperation between Turkey and Russia in Central Asia. Such interactions can be carried out through Russian law enforcement agencies (Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation, Federal Service for the Control of Narcotics, and the Federal Migration Service) and the relevant government agencies in Turkey, as well as TAKM.

Turkey and Russia can expand bilateral cooperation in Central Asia if they manage to buffer the above spheres of mutual interest against various political differences and pressure from the US and certain European countries, which are jealous of the formation of such partnerships. Given the nature of the new challenges posed by the unpredictable situation in Afghanistan after 2014, Russia could continue to develop cooperation with Turkey in the region, despite the existing disagreements with it on a number of international issues. This is all the more so because there are no conflicts of interest between Turkey and Russia in the region, and the matter at issue may be only some division of the spheres of influence.

Given that Turkey's foreign policy priorities in the post-Soviet space are focused mainly on the Caucasian and the Black Sea-Caspian geopolitical zones, while for Russia these zones as well as the Central Asian and European part of the CIS are of equal priority, Russian-Turkish cooperation in Central Asia has certain constraints and limits. In addition, the extent of Russian-Turkish cooperation in Central Asia is not so great.

In addition, both states are pursuing their own goals in the region that often diverges in cultural and civilizational terms as well as priorities.

Russia seeks to use soft power instruments to expand the influence of the Russian language and culture in Central Asia, and to create an atmosphere of political alliance and partnership based on the common history of the peoples of Russia and Central Asian countries. Turkey is promoting the idea of the “common Turkic home,” common for Turkey and the Central Asian states (Turkic) language. Among other things, it is actively promoting the transition from the Cyrillic to the Latin alphabet in Central Asia and seeks to become the new cultural and political center of gravity and even the driver of the “common-Turkic” integration project, an alternative to Russian.

So, speaking of a full-fledged partnership between the two countries in the Central Asian region is somewhat premature. Rather, with regards to Central Asia, we can speak of a Russian-Turkish competitive rivalry, especially in such areas as energy, culture, and economic integration.

1. Vneshnjaja torgovlja Rossijskoj Federacii po osnovnym stranam za janvar'-dekabr' 2013 g. Federal Customs Service of Russia. http://www.customs.ru/attachments/article/18871/WEB_UTSA_09.xls

2. D. B. Malysheva. Central'noaziatskij uzel mirovoj politiki. Moscow, RAS IMEMO, 2010. p. 66.

3. Beshimov B., Satke R. The struggle for Central Asia: Russia vs. China // Aljazeera. March 12, 2014. URL: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2014/02/struggle-central-asia-russia-vs-201422585652677510.html

4. Turkey’s development cooperation. General characteristics and the least developed countries. - Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs. URL: http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey_s-development-cooperation.en.mfa

5. Region Kaspijskogo morja v ijune 2014 goda. June 3, 2014. URL: http://casfactor.com/ru/editor/56.html

6. Simvol edinstva tjurkskih narodov. - Jeho. Baku, June 6, 2014 , URL: http://www.echo.az/article.php?aid=6424

7. Fedorenko V. The New Silk Road initiatives in Central Asia. August 2013, Rethnik Institute, Wasington, pp. 9, 11.

8. http://www.kazembassy.by/politic/megdunar.html

9. T. Ibraev. S jataganom za pazuhoj. – Namad, March 3,2014. URL: http://www.nomad.su/?a=3-201403110016

10. Kazahstan vozglavit sojuz voennyh sil pravoporjadka tjurkojazychnyh gosudarstv v 2016 godu. - Delovoj Kazahstan, September 24, 2014 URL: http://dknews.kz/kazahstan-vozglavit-soyuz-voenny-h-sil-pravoporyadka-tyurkoyazy-chny-h-gosudarstv-v-2016-godu/

11. Turkey delivers security experience to Central Asia via TAKM. - Today’s Zaman, Istambul, 10.02.2013. URL: http://www.todayszaman.com/_turkey-delivers-security-experience-to-central-asia-via-takm_306586.html.

12. See the official TAKM site http://www.jandarma.tsk.tr/ing/dis/takm/takm_en.htm

13. http://inosmi.ru/overview/20130131/205305517.html.

14. See M. Kalishevskij Tjurkskoe edinstvo protiv Evrazijskogo sojuza? – Fergana, October 25, 2011. http://www.fergananews.com/ARTICLE.php?id=7147.

15. Aleksej Uljukaev i Nihat Zejbeki obsudili vozmozhnosti sozdanija zony svobodnoj torgovli Rossii i Turcii. Ministry of Economic Development, September 16, 2014 http://economy.gov.ru/minec/press/news/201409165.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |