Russian-Mexican ties are over 100 years old, and are unique, since the USSR had no other Latin American partner, apart from Cuba, with which it maintained such an intensive political dialogue despite numerous political and economic differences.

The 1990s have opened the curtains on a new stage in the bilateral relationship, with the two countries almost simultaneously dwelling upon political, economic and social modernization. Substantial changes to the world order also raise the need for new forms of interaction between Moscow and Mexico City.

Similar Positions

The disintegration of the bipolar system and emerging contours of a unipolar world have prompted Mexico to step up international efforts to promote the principles of multilateralism, respect for sovereignty, inadmissibility of forcible democratization, as well as peace and security with the United Nations playing a central role.

Mexico has always rejected unilateral interventions unsanctioned by the UN, whatever the pretext. For example, in 2003, the country fiercely opposed the U.S. invasion of Iraq despite colossal pressure from President Bush who spent almost an hour trying to persuade Mexican President Vicente Fox to approve the American-British resolution in support of the assault. Through shrewd backstage diplomacy, the Mexican ambassador to the UN (then a non-permanent Security Council member) and his Chilean colleague managed to impede the resolution’s progress to the Security Council [1].

There were certain Russian pundits who recommended that the Kremlin switch from principles to pragmatic goals and fall in with U.S. policies to preserve at least some economic positions in Iraq. As for U.S.-dependent Mexico, virtually everyone predicted its automatic support for Washington. But Mexico has vividly demonstrated that there still is some room for principles in world politics.

While Russian leaders also opposed the Iraq war, the episode seems to have prompted it to take a fresh look at this Latin American country and move significantly closer to Mexico on other global issues. Both countries bluntly condemned the 9/11 terrorist attacks and came out in support of the struggle against international terrorism and crime. At the same time, both rejected large-scale punitive operations and favored the eradication of the causes rooted in poverty and social and economic backwardness of some regions of the world.

Russia and Mexico share opinions on many pressing issues in global politics, primarily on the need to adjust international law to the current environment and ensure that it is rigorously observed, even in emergencies like the Arab Spring, Syrian crisis, U.S. trade and economic embargo against Cuba, etc. This dialogue received a major boost from the Russian-Mexican permanent bilateral commission set up following the 1996 visit by Evgeny Primakov to Mexico City. Disarmament and the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons are key issues under the commission's consideration.

Interestingly, it was Mexico that, in 1967, initiated a nuclear-free zone in Latin America, the first in the world. In March 2013, Mexico was very active at the Oslo Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons. The next event is to take place in Mexico, although the date has yet to be determined. The Russian-Mexican interplay should also acquire great significance during the preparations for the 2015 NPT Review Conference.

Mexico traditionally advocates a stronger international security regime and its adaptation to the current situation. Not coincidentally, it is the only country in the Western Hemisphere to have scrapped the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance of 1947 due to its obsolescence in September 2002. In bilateral consultations, Russia and Mexico attach much attention to improving mechanisms to protect human rights at a global level, particularly within their efforts in the UN Human Rights Council.

Mexico's New Role

In recent years, Mexico has become increasingly active in international multilateral forums, aiming to strengthen mechanisms for collective decision-making and enhance the coordination of global initiatives on sustainable development, as was apparent in Mexico's work at the G20 summit it chaired in 2012.

In June 2012, the seventh G20 summit took place in the Mexican city of Los Cabos. Suggested by Mexico, the agenda included five pressing issues directly connected with Russia's interests, i.e. economic stabilization and structural reforms for growth and employment; strengthening financial systems for stimulating economic growth; improving the world's financial architecture in the globalized economic environment; food security and measures to stabilize commodity prices; concerted efforts to advance sustainable development and the green revolution; and more financing to overcome the adverse consequences of climate change. On November 28, 2012, Mexico devolved the G20 presidency in 2013 to Russia.

Mexico became the second Latin American country, after Chile, to join the OECD – which is currently headed by a Mexican: Angel Gurria. Given Russia's future entry into the group, it seems reasonable to include the accession procedure in the Russian-Mexican agenda, especially as Mr. Gurria has frequently visited Moscow to discuss the issue.

Mexico is active in the talks on climate change and as part of the Environmental Integrity Group which is intended to attain global ecological integrity, i.e. a sustainable ecological system, supporting its ability for self-regulation and self-restoration following adverse external action. Mexico also backs reforms to the UN, including the Security Council, on which it differs from other Latin American states by opposing the veto power.

Mexico's international role has grown significantly recently, as the country is becoming an influential participant in developing new mechanisms for global regulation, ever more frequently dissociating from key Western states led by the United States. Note that Mexico, Argentina and Brazil are the only Latin American states in the G20, while Mexico's accession to BRICS also seems timely.

New Geopolitical Scenarios

There is also heightened attention on Mexico as a result of the new geopolitical situation, since the country has moved into the epicenter of fundamental, if not tectonic, shifts in the global economy connected with large-scale projects such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership aiming to boost ties between U.S.-led NAFTA and Asia Pacific, on the one side, and the establishment of a free-trade area between NAFTA and the European Union, on the other.

Both are Washington-led initiatives. The first is aimed at creating a substitute for APEC and containing China's expansion and the second at building a durable transatlantic bridge and strengthening its role in a Europe that has been weakened by the financial and economic crisis. If the two projects are implemented, Mexico's significance in world politics can be expected to grow. Rather than hesitating, Russia should adjust to the emerging political architecture in order to avoid the risk of being globally marginalized.

An Opportunity to Grasp

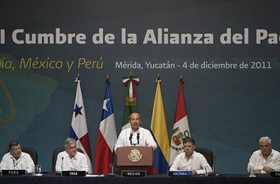

In recent years, Mexico has effectively been positioning itself as a link between the Western Hemisphere’s North and South, among other things through its integration initiatives, i.e. the 2012 Pacific Alliance uniting the continent's four largest Pacific states (Mexico, Colombia, Peru and Chile) [2].

Some countries, chiefly Japan, have already joined the Pacific Alliance as observers. Seemingly unrelated to the Asia Pacific region, Spain also intends to follow suit.

Russia has repeatedly shown an interest in establishing stable ties with Latin American integration processes, although to date with no palpable success. In recent years, Moscow has been working to expand its presence in the Asia Pacific region beyond APEC. However, it seems to lack the resources needed, while the long-term program for the development of East Siberia and the Far East, significantly boosted by the 2012 APEC summit on Russky Island, is not enough to bridge this gap.

Russia essentially lacks cross-Pacific links either with Mexico, its geographically closest potential partner in Latin America, or with the other 11 countries in the region on the Pacific coast. The situation is all the more regrettable as after World War II Soviet leaders considered establishing stable shipping lines connecting the Far East with Pacific ports in Latin America. For decades, experts have been calling for a trans-Pacific bridge to be created [3]. The project would not only boost these regions’ development but would also diversify Russia's trade and economic relationships and feed into the dynamic integration processes in the Asia Pacific region. To this end, some kind of attachment to the Pacific Alliance, led by Mexico, is sure to bring Russia tangible dividends.

* * *

Russia and Mexico share a great many common interests in global politics. Their cooperation potential is realized to an extent, but a significant amount of untapped potential remains. In future, a great deal will depend on Russia's ability to drop its stereotypes about Latin America as the United States’ backyard – where Russia stands no, or little, chance. As far as Mexico is concerned, it is not just a Latin American country but an influential global actor connected with Russia not only through this history but also, hopefully, by the future.

There seems to be an opportunity for success in uniting their efforts to adapt international law to the current global challenges. It is worth noting that Mexico has produced a constellation of international lawyers who have developed the status of the nuclear-free area, the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States, reforms to the law of the sea, etc. Hence, Russian-Mexican interaction could be quite fruitful in areas such as strengthening the nonproliferation regime, future disarmament initiatives, and upgrading the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea regarding piracy at sea, which is currently a serious global threat.

Joint efforts also appear promising in the international law on migration, in particular in terms of specifying the migrant's status, rights and obligations. This problem is quite pressing both for Mexico, a recipient and a transit country for migration flows to the United States from of the southern Western Hemisphere, and for Russia – which faces a decade-long chaotic wave of migrants from ex-Soviet republics.

Bilateral consultations and exchanges could be expanded by the discussion of drug trafficking and organized crime. Mexico has accumulated rich, although far from consistently successful, experience in handling these problems, which radically worsened in the mid-2000s, during which period they also become increasingly pressing in Russia.

The two states might was well broaden their cooperation in preparing and convening multilateral forums, such as the G20 summits, since developing new approaches to global regulation, especially in financial, economic and political fields, should serve both countries’ interests.

As for the Mexican economic ties to the United States, this is more related to interdependence, albeit within an asymmetrical pattern. Back in power after the 2000-2012 opposition, the Institutional Revolutionary Party has always tried to compensate the economic dependence on the United States by dynamic foreign policy. Since the party has often sought to put distance between itself and Washington, and sometimes openly opposes its policies, the U.S. factor is not likely to noticeably affect the expanding Russian-Mexican dialogue.

1. V.P.Sudarev. The Two Americas after the Cold War. Moscow: Nauka Publishers, 2004, p. 98.

2. El Nuevo Herald (Miami), 06.10.2012.

3. Latin America Journal. 2013. № 6. P. 68.