Russia and Georgia against Radical Islamism: Common Threats and Opportunities for Cooperation

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Ph.D in History, Leading Research Fellow at MGIMO University, Editor-in-Chief of International Analytics Magazine, RIAC Expert

It is widely accepted that Russia and Georgia are tough and irreconcilable opponents with differences and disagreement over a wide range of issues. At the same time, Moscow and Tbilisi often face common threats, and the lack of dialogue, interaction, and, consequently, trust impedes their ability to effectively address these dangerous challenges. Below we discuss the two countries’ attempts to counter radical Islam, their prospects for cooperation and difficulties in developing common approaches.

It is widely accepted that Russia and Georgia are tough and irreconcilable opponents with differences and disagreement over a wide range of issues. At the same time, Moscow and Tbilisi often face common threats, and the lack of dialogue, interaction, and, consequently, trust impedes their ability to effectively address these dangerous challenges. Below we discuss the two countries’ attempts to counter radical Islam, their prospects for cooperation and difficulties in developing common approaches.

Russia and Georgia: from Confrontation to Normalization

Over the entire period since the collapse of the Soviet Union, bilateral Russian-Georgian relations have experienced complex and extremely contradictory dynamics. After the five-day war in August 2008, ties reached a low point. Diplomatic relations were severed, and interstate contacts were confined to the Geneva discussions on the situation around ethno-political conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia [1] and negotiations through intermediaries on Russia's accession to the WTO (through the mediation of Switzerland) or the opening of the Kazbegi-Upper Lars checkpoint on the Georgian Military Road (through the mediation of Armenia).

However, following the parliamentary elections in October 2012 and the presidential campaign in October 2013, the Georgian parliament, government and head of state changed, and normalizing Russian-Georgian relations moved from the realm of discussion and debate to that of practical accomplishments. During this period, Moscow and Tbilisi have managed to implement a number of measures that clearly contrasted with the negative trends which had developed earlier. The obvious results of this first stage of the normalization include:

- A renouncement of confrontational rhetoric and the practice of using Russia for purposes of internal political mobilization by the official authorities in Georgia (during the presidential elections in 2013 only the oppositional United National Movement used this tactic).

- Tbilisi's refusal to support the North Caucasus nationalist movements and a political alliance with them on the basis of positioning Georgia as the “Caucasian alternative” to Russia.

- Reversal of the Sochi Olympics boycott and the decision to send a delegation of athletes to the Games.

- A declaration of a willingness to cooperate on security issues [2].

- The opening of the Russian market for Georgian goods (alcoholic beverages, mineral water, citrus fruits, etc.) [3].

- Simplification of the visa regime for Georgian transport operators (drivers).

- The establishment of a direct dialogue on a regular basis between representatives of Georgia and Russia (Special Representative of the Georgian government Zurab Abashidze and State Secretary, Deputy Foreign Minister Grigory Karasin), which is free from disputes over the status of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation (February 2013) contains a provision that “Russia is interested in the normalization of relations with Georgia in the areas in which the Georgian side shows its willingness” [4].

On February 10, 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin, answering a Georgian reporter's question during the Winter Olympics in Sochi, did not rule out the possibility of meeting with his Georgian counterpart Giorgi Margvelashvili in the future [5].

Thus, Moscow and Tbilisi have managed to put the dialogue into a format of pragmatic communication. At the same time it should be noted that the initial agenda of normalizing relations has been almost exhausted, while current baggage offers little room for further practical steps. There is a need to identify problems and formats that would give a new impetus for a significant improvement in relations. The threat of terrorism and security issues by all means belong to this category. Problems are quite pressing in the Russian North Caucasus (especially Dagestan, Ingushetia, Chechnya) and northern Georgia (the Pankisi Gorge).

Terrorism and Russian-Georgian Border Zone Security

The importance of the North Caucasus for the Greater Caucasus (Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and the North Caucasus) geopolitical configuration is hard to overestimate. The prospects for improving Russian-Georgian relations are largely dependent on dynamics in the North Caucasus which is the most unstable region of Russia.

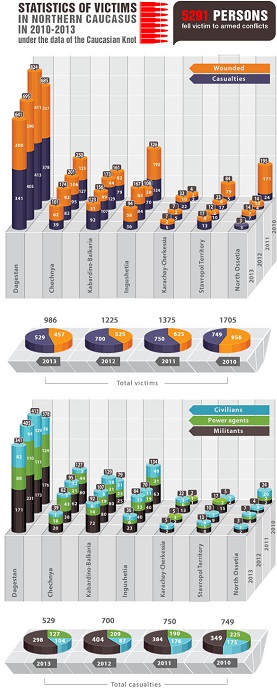

Despite a decrease in the total number of victims of the armed conflict in 2013 of around 239 people, or 19.5 percent as compared with the previous year, and the FSB head Alexander Bortnikov’s official announcement of the Caucasus Emirate leader Doku Umarov’s “neutralization”, the situation in this part of Russia is far from stable and secure [6].

First, although there as been a general reduction in the number of victims, civilian casualties have increased [7]. Second, from January 1 to December 30, 2013 in the South and North Caucasus federal districts, 33 terrorist attacks were committed, 9 of them by suicide bombers. Georgia has a common border with the three most dangerous (in terms of the terrorist threat and the spread of Islamic radicalism) North Caucasian republics, namely Ingushetia, Dagestan and Chechnya [8].

Suffice it to say that three out of the nineteen entities on the Unified Federal list of organizations recognized as terrorists by the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation are associated with the North Caucasus (the remaining 16 are based abroad, mainly in the Middle East, Afghanistan, and Pakistan). These three include the Supreme Military Majlis ul-Shura of the United Mujahideen Forces of Caucasus, the Congress of the Peoples of Ichkeria and Dagestan and the Caucasus Emirate [9]. The last of the three above-mentioned terrorist organizations is the only entity operating on Russian territory which is on the “terrorist list” of a foreign state, namely the United States [10].

North Caucasian terrorists spread instability far beyond the region itself. Their terrorist attacks took place on the railroad system (the attack in 2009 on the Nevsky Express train between Moscow and St. Petersburg) [11], in Moscow (the subway and Domodedovo airport explosions in 2010 and 2011 respectively) [12], in Volgograd (city bus, railway station building and trolley coach explosions) and in Pyatigorsk in 2013. North Caucasus jihadists claimed activity within the territory of the Volga Federal District too [14].

Units of radical Islamists in Georgia’s border areas with Russia (Akhmeta district) have been considerably strengthened recently not only by migration from the North Caucasian republics, but also by radicalization. These units tend to establish strong ties with the terrorist organizations operating in Russia's North Caucasus, as well as with international organizations. According to the head of the Caucasus Integration Foundation and a prominent member of the Council of Elders of the Pankisi Gorge Umar Idigov, about two hundred ethnic Chechens-Kistinians from Pankisi are currently involved in the civil war in Syria [15]. At the same time, the jihadists of the so-called Caucasus Emirate mark Transcaucasian territories (including Georgia) as “lands occupied by infidels and apostates.” [16]

Russia is extremely interested in preventing the Georgian border area from becoming the rear zone or safe haven for militants from the North Caucasus republics. At the same time, the further destabilization of the Russian territories in the North Caucasus poses a threat not only to Russia, but Georgia as well. Should developments follow a worst-case scenario, there would be no “civilized secession” and transformation of the constituent territories of the Russian Federation into viable state entities. Another wave of instability would provide Georgia no benefits (other than the short-term satisfaction from gaining compensation for the loss of Abkhazia and South Ossetia), and would create a vacuum of strength, power and security, as well as new threats not only to Moscow, but also to Tbilisi. In this case, Georgia would be left alone to deal with the growing Islamist threat, which is a much more precarious challenge than the loss of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. To prevent this scenario, Russia and Georgia should concentrate on analyzing the not too successful previous experience of containing the terrorist threat, which in practice boiled down to a “zero-sum game”, rather than cooperation.

The Impact of the North Caucasus on International Security

Apart from the regional and Russian dimensions, security in the North Caucasus has an international significance as well. The latter is an essential context for assessing the development of relations between Russia, Georgia and the West. It is not accidental that on May 26, 2011, the U.S. State Department identified the Caucasus Emirate as a threat to the national interests of not only Russia, but the United States too [17]. The year before the Caucasus Emirate leader Doku Umarov was included on the list of terrorists whose activities constitute a threat to American interests [18].

The biggest terrorist attack in the United States after September 11, 2001, which occurred during the Boston Marathon, made two brothers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev of Avar-Chechen origin notorious worldwide. In 2011, the FBI, on the request of the Russian FSB, interviewed the eldest of them Tamerlan (killed in the operation to capture suspected terrorists) on his possible ties with the North Caucasus underground [19]. In 2012, he stayed in Russia's North Caucasus for six months, where, in all likelihood, he had contacts with jihadists’ representatives [20]. Although it is the jury that will have the final say in this process, the controversy over the Tsarnaev case made Washington not only officially minimize its criticism of Russian actions in the North Caucasus, but also intensify cooperation to ensure safety of the Games in Sochi.

One of the central issues of today's international agenda is the situation in the Middle East in general, and in Syria in particular. Although Moscow and Washington have reached a compromise regarding the disposal of chemical weapons stockpiles of Bashar al-Assad’s government, the civil conflict in Syria continues. The Russian leadership is extremely concerned about the involvement of North Caucasus natives in the Middle East conflict. This is one of the factors that shapes Moscow's attitude towards the Syrian conflict. So, in September 2013 Sergey Smirnov, FSB First Deputy Director, revealed that about 300-400 Russian citizens were fighting in the Syrian civil war on the side of President Bashar al-Assad’s opponents [21]. At the same time one of the largest foreign groups involved in the conflict was a Caucasian unit Kataeb al-Muhajireen headed by an ethnic Chechen Abu Abdurahman [2]. In mid-July 2013, the leadership of the Chechen Republic confirmed the participation of ethnic Chechens in the events in Syria. In his September speech Sergey Smirnov emphasized that the natives of the North Caucasus could return home, bringing new destabilization with them [23].

Pankisi as a Zero-Sum Game and Regional Model

Over the last two decades, the Russian-Georgian border has repeatedly been in the limelight through reports on security issues in the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia. Following the outbreak of the second Russian campaign in Chechnya in 1999, Georgia opened its borders to receive Chechen refugees. However, the refuge in Pankisi was discovered not only by refugees but by Chechen separatist combat groups too (the notorious warlord Ruslan Gelayev was the leader of one of them).

Georgian authorities initially denied the presence of militants in the Pankisi area and emphasized the humanitarian problems of the refugees. But after September 11, 2001, Tbilisi's position changed. In April 2002, the United States and Georgia signed an agreement on the Train and Equip military aid program which provided for the training of two thousand Georgian special service personnel [24]. The official purpose of the agreement was to fight terrorists in Pankisi. On May 25, 2002, the minister of state security of Georgia Valery Khaburdzania officially acknowledged that there were 700 Chechen separatists and 100 Arab mercenaries in the Pankisi Gorge. In August 2002, a group of Chechen fighters crossed the Russian-Georgian border [25].

Shortly thereafter, President Vladimir Putin said that if Tbilisi failed to put an end to Chechen groups’ activities, Russia reserved the right to intervene [26]. However, the U.S. disagreed with the Russian initiative of preventive strikes in Pankisi. The position of the U.S. administration was as follows: the fight against Chechen terrorists and separatists was necessary, but on the basis of the territorial integrity of Georgia and without Russian military intervention. From September 2002 to early 2003, Georgian authorities carried out an “anti-criminal operation” in Pankisi. About 40 people suspected of terrorist and criminal activities were detained. However, most of the fighters dispersed to other parts of the Russian-Georgian border region. Nevertheless, government raids in Pankisi forced Amzhet (Abu Hafs), a warlord of Arab origin who had links with Al-Qaeda, to leave the region [27]. While Moscow was critical of the effectiveness of the operation, the situation in the gorge improved.

Although these actions did stabilize the situation, they failed to drastically improve it. Border areas were not integrated enough into the overall social, economic and cultural life of Georgia. Having focused on the situation in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the central authorities of Georgia paid little attention to the processes of Islamic Revival, which reflected problematic rather than positive aspects. As a result, the region formed its own informal Islamic groups, including extremist units. Certain representatives of the ruling establishment during the presidency of Mikheil Saakashvili presidency cherished illusions that radical Islamists could be an effective instrument to weaken Russia. However, in late August 2012 the Gorge of Lopota incident involving a group of about 20 armed Islamist militants came as a severe shock to Georgia. The gunmen seized several groups of hostages. The Georgian Interior Ministry conducted an operation to block this subversive group, which was officially concluded on August 30, 2012. During the clashes, eleven militants and three Georgian Interior Ministry commandos were killed [28]. Several militants that were killed turned out to be Georgian citizens residing in Pankisi. Although the Interior Ministry and the government denied the existence of Georgian citizens among the militants, investigations by journalists revealed the names of the young people killed from Pankisi (according to journalists, they were all 19-25 years old and had been radicalized) [29].

Sergei Markedonov:

Russia and Conflicts in the Greater Caucasus:

In Search for a Perfect Solution

The policies of the previous administration in the North Caucasus underwent a dramatic revision when the new government led by the Georgian Dream party came to power. Cooperation between the two countries in the fight against terrorism has been recognized to be in keeping with Georgia’s national interests (although until now, it has boiled down to ensuring security during the Olympic Games in Sochi). However, the lack of trust between the parties still remains the main obstacle along the way of promoting anti-terror cooperation. The known involvement of the Georgian special services and law enforcement departments in cooperation with the U.S. and NATO cannot but arouse suspicions on the part of their Russian partners. The general context of the Russian-Georgian relations, including the unresolved problems of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, hampers an exit from from zero sum game too.

The Ukrainian crisis creates additional challenges for improving relations. The political class and the expert community of Georgia view the Crimean situation through the prism of their loss of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and as a distinctive manifestation of the Kremlin’s imperial policy. On March 6, 2014 the Georgian parliament adopted a resolution on “Supporting Sovereignty and the Territorial Integrity of Ukraine,” in which it condemned Russia's actions [30]. Georgian President Giorgi Margvelashvili called on the international community to assess Russia’s actions against Ukraine “calmly, but in a principled way” [31].

Having postponed their meeting several times, representatives of Russia (Grigory Karasin) and Georgia (Zurab Abashidze) failed to meet in March 2014. In a telephone conversation on March 21, both diplomats agreed on a meeting some time later [32]. However, such a postponement may have a positive effect. It would be wrong to discuss pressing issues in an emotional atmosphere, particularly if emotions sweeping the Russian and Georgian societies differ that much. There is a great risk that the Ukrainian context will be brought into the diplomats’ dialogue and overshadow Russian-Georgian issues. Therefore, the postponement of the meeting until the situation around the Ukrainian elections and the South-East of Ukraine clarifies may benefit not only Moscow but Tbilisi as well.

Recommendations

Russian-Georgian relations suffer from unresolved status disputes, and at the same time necessitate pragmatic cooperation to fight a common enemy, namely terrorism fueled by ideas of radical Islamism.

Therefore, the establishment of cooperation over security issues could be an important step in moving from the initial (mostly rhetorical) agenda of normalizing relations to a more meaningful process. Cooperation on security issues during the Olympic Games in Sochi has already laid the groundwork for progress in this direction. The Russian and the Georgian authorities have both displayed particular interest in this sphere.

It would be advisable to continue this cooperation after the Games. It seems reasonable to revive the idea discussed before the dramatic deterioration of bilateral relations in 2004-2006. At issue was the creation of joint anti-terrorist centers, which originally were to be located at military facilities of the Russian Transcaucasus Group of Forces. To date, the background (as well as the foreign policy context) for discussing this issue has changed dramatically. However, the idea seems quite constructive, especially with regard to the areas of Chechnya, Ingushetia and Dagestan areas along the state border.

This idea is not easy to implement. Many problems remain, including surrounding the level of representation in the joint centers, the volume and quality of information, the location of the centers, and the level of trust between the parties. However, the implementation of this long-term project over several stages is sure to yield tangible practical results in due time.

1. Geneva talks on the situation in the Caucasus started on October 15, 2008. This format provides for the participation of Russia, Georgia, the United States, the European Union, the United Nations and the OSCE, as well as diplomats from Abkhazia and South Ossetia as "experts", who do not represent their territorial entities as sovereign countries. Discussions are underway on two tracks, namely security and humanitarian aspects. As of April 1, 2014, 27 rounds of discussions had been held.

2. During his visit to Washington in August 2013 , Georgian Defense Minister Irakli Alasania spoke about the desirability of cooperation to ensure the safety of the forthcoming Olympics in Sochi “despite the dead hand of the military conflict in 2008” (Alasanija: Gruzija otkryta dlja voennogo sotrudnichestva s Rossiej // Vzgljad. August 22, 2013. URL: http://vz.ru/news/2013/8/22/646647.html). During a meeting with journalists at the Tbilisi Sheraton Metechi Palace on January 16, 2014, Prime Minister of Georgia Irakli Garibashvili stated: “Security issues are very important, and we must cooperate on these problems with all countries, including Russia. If during the Olympics, Georgia can contribute to strengthening security and safety, we can only be happy” (Gruzija gotova sotrudnichat' s RF v bor'be s terrorizmom v Sochi // RIA Novosti. January 16, 2014 . URL: http://ria. ru/world/20140116/989528899.html).

3. From January to September 2013, the volume of mineral water exports from Georgia to Russia made up about 22-24 million dollars. In the final quarter of 2013, Georgian producers sold wine in Russia worth roughly 40 million dollars, although in the beginning of the year the figure did not surpass 20 million (Vozobnovlenie jeksporta vina v RF — odno iz glavnyh sobytij goda dlja Gruzii // Golos Rossii. January 1, 2014 . URL: http://rus.ruvr.ru/2014_01_01/Vozobnovlenie-jeksporta-vina-v-RF-odno-iz-glavnih-sobitij-goda-dlja-Gruzii-4667). In December 2013, Russia left Ukraine behind as the main importer of Georgian citrus crops (Gruzija jeksportirovala okolo 40 tysjach tonn citrusovyh // Agroperspektiva. December 27, 2013.URL: http://www.agroperspectiva.com/ru/news/128098).

4. The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation (February 12, 2013) / / Garant website. February 20, 2013. URL: http://www.garant.ru/products/ipo/prime/doc/70218094/# ixzz2vYOKymKL.

5. Putin ne iskljuchil vozmozhnosti vstrechi so svoim gruzinskim kollegoj // ITAR-TASS. February 10, 2014. URL: http://itar-tass.com/politika/953439.

6. «Kavkazskij uzel» proanaliziroval itogi 2013 goda na Severnom Kavkaze: chislo zhertv vooruzhennogo konflikta sokratilos' // Kavkazskij uzel. January 1, 2014. URL: http://www.kavkaz-uzel.ru/articles/237362.

V Moskve pod rukovodstvom Predsedatelja NAK, Direktora FSB Rossii A. V. Bortnikova provedeno 45-e zasedanie NAK // National Anti-Terrorism Committee (official site) April 8, 2014. URL: http://nac.gov.ru/nakmessage/2014/04/08/v-moskve-pod-rukovodstvom-predsedatelya-nak-direktora-fsb-rossii-av-bortnikova.html.

7. «Kavkazskij uzel» proanaliziroval itogi 2013 goda na Severnom Kavkaze.

8. Over the first nine months of 2013, the largest number of law enforcement officers were killed by militants in Dagestan (over 70 people) and Chechnya (more than 20), see: Svyshe 200 boevikov, v tom chisle bolee 30 liderov bandformirovanij, unichtozheny na Severnom Kavkaze za 9 mesjacev // Interfaks. November 28, 2013. URL: http://interfax-russia.ru/South/main.asp?id=454880.

9. Unified Federal list of organizations recognized as Terrorists by the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation / / National Anti-Terrorism Committee (official site). February 14, 2003. URL: http://nac.gov.ru/document/832/edinyi-federalnyi-spisok-organizatsii-priznannykh-terroristicheskimi-verkhovnym-sudom-r.html.

10. Designation of Caucasus Emirate. Media Note // U.S. Department of State. May 26, 2011 URL: http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2011/05/164312.htm; Designation of Caucasus Emirates Leader Doku Umarov // U.S. Department of State. June 23, 2010. URL: http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2010/06/143579.htm. For U.S. motives see; Markedonov S. Caucasus Cauldron // Journal of International Security Affairs. 2010. № 19 (Fall). PP. 123-128.

11. Boeviki Umarova vzjali otvetstvennost' za podryv «Nevskogo jekspressa» // Vek. December 2, 2009. URL: http://wek.ru/boeviki-umarova-vzyali-otvetstvennost-za-podryv-nevskogo-yekspressa.

12. Dokku Umarov vzjal na sebja otvetstvennost' za vzryvy v Moskve i poobeshhal ocherednye terakty // Kavkazskij uzel. March 31, 2010. URL: http://russia.kavkaz-uzel.ru/articles/167225. Dokku Umarov vzjal otvetstvennost' za terakt v «Domodedovo» // Kavkazskij uzel. February 8, 2011. URL: http://www.kavkaz-uzel.ru/articles/180723.

13. FSB: terakty v Volgograde i v Pjatigorske raskryty // Rossijskaja gazeta. April 8, 2014. URL: http://www.rg.ru/2014/04/08/reg-ufo/teracty-anons.html.

14. For details see: Sergey Markedonov. The Rise of Radical and Nonofficial Islamic Groups in Russia’s Volga region // Center for International and Strategic Studies. January 2013. URL: http://csis.org/publication/rise-radical-and-nonofficial-islamic-groups-russias-volga-region.

15. Idigov: v grazhdanskoj vojne v Sirii uchastvujut okolo 200 chechencev-kistincev iz Gruzii // Kavkazskij uzel. November 20, 2013. URL: http://www.kavkaz-uzel.ru/articles/233822.

The Pankisi Gorge is located in the northern part of the Kakheti historical region. Its territory stretches for 34 kilometers from the Big Borbalo Mountain of the Main Caucasian ridge in the north to the Matani village in the south. The territory of the Pankisi Gorge is part of the Georgian Akhmeta district. In the 19th century immigrants from mountainous parts of Chechnya and Ingushetia moved to Georgia and settled in several villages. The Georgians called them “Kists”, pointing to their Vainakh origin. According to the 2002 Georgian census, the number of Kistinians numbers around 7.1 thousand people.

16. A. Chepurin Tendencii politicheskogo razvitija stran Zakavkaz'ja v svete antiterroristicheskoj operacii // SA&CC Press. 2003. URL: http://www.ca-c.org/journal/2003/journal_rus/cac-03/07.cherus.shtml.

17. Designation of Caucasus Emirate. The Caucasus Emirate is a subversive and terrorist group, declaring itself an Islamic state. It was proclaimed on October 7, 2007 by the so-called President of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria Doku Umarov, who completed the transformation of the Chechen Islamist nationalist underground into a structure aimed at propping up the terrorist struggle in the entire North Caucasus and supporting Islamists in the Caucasus and the Volga region. It consists of different units (Jamaats or fronts) sharing common (radical jihadist) ideological views and united in a network.

18. Designation of Caucasus Emirates Leader Doku Umarov.

19. FBR doprashivalo Carnaeva po zaprosu FSB // Interfaks. April 22, 2013. URL: http://www.interfax.ru/world/302856.

0. Dagestanskij sled Tamerlana Carnaeva // Bol'shoj Kavkaz. April 22, 2013. URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y31Vn1_76g4.

21. FSB: v Sirii vojujut 300-400 naemnikov iz Rossii // Kavkazskij uzel. September 20, 2013. URL: http://www.kavkaz-uzel.ru/articles/230365.

22. V Sirii vojujut do tysjachi chechenskih boevikov, sobrannyh v odin otrjad «Al'-Muhadzhirin» // Newsru.com. September 19, 2013. URL: http://www.newsru.com/world/19sep2013/chechsiria.html.

23. Emil Souleimanov. North Caucasian Fighters Join Syrian Civil War // The Central Asia — Caucasus Analyst. August 27, 2013. URL: http://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/12794-north-caucasian-fighters-join-syrian-civil-war.html; Alissa De Carbonel. Insight — Russia Fears Return of Fighters Waging Jihad in Syria // Reuters. November 14, 2013. URL: http://uk.reuters.com/article/2013/11/14/uk-russia-caucasus-syria-insight-idUKBRE9AD06820131114.

24. Georgia Train and Equip Program Begins // U.S. Department of Defense. April 29, 2002. URL: http://www.defense.gov/releases/release.aspx?releaseid=3326.

25. A. Chepurin. Tendencii politicheskogo razvitija stran Zakavkaz'ja v svete antiterroristicheskoj operacii.

26. M. Muradov, M. Varyvdin. Svoevremennaja vylazka Ruslana Gelaeva // Kommersant. September 27, 2002. URL: http://www.kommersant.ru/doc/343116

27. G. Gotua G. «Al'-Kaida» vse-taki byla v Pankisi. No sejchas ee tam net // Kommersant. January 23, 2003. URL: http://www.kommersant.ru/doc/360685.

28. MVD Gruzii soobshhilo ob okonchanii osnovnoj fazy specoperacii v ushhel'e Lopota // Kavkazskij uzel. August 30, 2012. URL: http://www.kavkaz-uzel.ru/articles/211931

Gorge of Lopota stretches for about 30 km along the southern slope of the Caucasus and is a part of the Telavi district in the Georgian region of Kakheti.

29. The names of Aslan Margoshvili and Bagauddin Aldamov were revealed. See:O. Vartanjan. Kogo na samom dele ubili v Lopotskom ushhel'e? // Jeho Kavkaza. September 3, 2012. URL: http://www.ekhokavkaza.com/content/article/24696837.html.

30. Parlament Gruzii prinjal rezoljuciju po Ukraine, no ne smog projavit' edinodushie // Kavkaz Online. March 7, 2014. URL: http://kavkasia.net/Georgia/2014/1394176712.php.

31. Margvelashvili prizval mezhdunarodnuju obshhestvennost' spokojno, no principial'no ocenit' sushhestvujushhee polozhenie // Gruzija Online. March 19, 2014. URL: http://www.apsny.ge/2014/pol/1395274017.php.

32. Peregovory Rossii i Gruzii ischerpali sebja, zajavljajut gruzinskie politologi // Kavkazskij uzel. March 22, 2014. URL: http://www.kavkaz-uzel.ru/articles/239864.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |