Portugal and PIGS: Main Lessons of Economic Recovery

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Ph.D in Economics, Deputy Director of the RAS Institute for Europe, Head of the Country and Regional Researches Department, Head of the German Research Center

In mid-May last year, Portugal officially exited the financial assistance program launched in 2011 by the European Union, European Central Bank, and International Monetary Fund. Although it was not the first country to turn its back on these loans (Ireland had that honor), Portugal has attracted significant public attention. After a painstaking implementation of international creditors’ guidelines, Lisbon has progressed along the path of reform and returned to the world credit market. Spain and Greece have also been rather successful in bridling the negative economic trends to prove that PIGS countries offer a good example of the focused execution of complicated homework.

In mid-May last year, Portugal officially exited the financial assistance program launched in 2011 by the European Union, European Central Bank, and International Monetary Fund. Although it was not the first country to turn its back on these loans (Ireland had that honor), Portugal has attracted significant public attention. After a painstaking implementation of international creditors’ guidelines, Lisbon has progressed along the path of reform and returned to the world credit market. Spain and Greece have also been rather successful in bridling the negative economic trends to prove that PIGS countries [1] offer a good example of the focused execution of complicated homework.

PIGS: P for Portugal

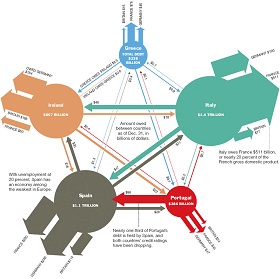

Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain emerged from the 2008-2010 global financial crisis virtually insolvent [2], with signs of recovery from the painful recession appearing only in 2013. Since these countries’ economic potentials (see Table 1) and macroeconomic problems differ, mechanisms for handling the problems also varied. The only common denominator has been large-scale external support conditioned by concrete structural demands from the aid providers.

Table 1.Key Economic Indicators in PIGS Countries, Italy and the Eurozone 2013

| Country | Population, million | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, billion euro | Per capita euro | Total | 15-24 age group | ||||

| Portugal | 10,49 | 166 | 15800 | 129,0 | 15,4 | 34,8 | |

| Greece | 11,06 | 182 | 17400 | 175,1 | 27,4 | 57,3 | |

| Spain | 46,73 | 1023 | 22300 | 93,9 | 25,8 | 54,9 | |

| Ireland | 4,59 | 164 | 35600 | 123,7 | 12,2 | 25,5 | |

| For comparison: | |||||||

| Italy | 59,69 | 1560 | 25600 | 132,6 | 12,5 | 41,8 | |

| Eurozone | 333,11 | 9600 | 28600 | 92,6 | 11,9 | 23,8 | |

Data used: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-GL-14-002/EN/KS-GL-14-002-EN.PDF

Abbreviated by Anglo-Saxon media as PIGS, Portugal followed Ireland in tackling the complex issues outlined by the creditors, and on May 17, 2014 officially declined external assistance. In contrast to other group members, Portugal’s economy bypassed the real estate collapse and the banking disaster. Its predicaments were structural: before 2008, the economy was sluggish, with national goods and services uncompetitive. The strong euro deprived the country of the benefits of devaluation, promoting imports and hampering exports, bringing about a steadily negative trade balance. Easy loans for households and economic entities resulted in skyrocketing debt, and all this came against the backdrop of worsening state finances: sovereign debt rose from 76 percent of GDP in 2009 to 97 percent in 2010 [3].

In June 2010, the Portuguese government adopted a recovery program focused on cutting government spending and increasing taxes. However, parliament rejected the package, forcing the government to resign. In spring 2011, when every hope of refinancing the state debt had evaporated, Portugal appealed to foreign creditors. In May 2011, the EU, European Central Bank, IMF, and Lisbon signed up to a three-year bailout and economic program that included a 78-billion-euro credit line. The European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and European Financial Stabilization Mechanism (EFSM) provided 26 billion euro each, while the IMF allocated 27.5 billion euro to encourage Portugal’s financial stabilization.

To meet the creditors' demands, the government took on austere economic policies incorporating lower budget spending, higher taxes, the privatization of state enterprises, labor market liberalization, an easier dismissal procedure, and improved education. A special commission was set up to monitor program implementation and produce advice for future loans.

Thanks to austerity, in 2013 the Portuguese budget deficit dropped to 2.6 percent of GDP, i.e. below the level set out in the recovery program [4]. The state became more able to finance domestic and foreign needs. Interest payments on state obligations were substantially reduced, with 10-year government bond yields reaching 3.58 percent, a record low since early 2006. From 2009 to 2013, exports’ share in GDP grew from 28 to 41 percent. Manufacturing sectors, especially shoemaking, improved their position on foreign markets, with services experiencing a dramatic uptick. Foreign investors read the signals: it was time to return to the Portuguese economy.

In contrast to other group members, Portugal’s economy bypassed the real estate collapse and the banking disaster. Its predicaments were structural.

In early May 2014, Lisbon declared the three-year program complete and stated its readiness to shun foreign creditors' support, as it had access to external funding and could repay loans without assistance.

Reforms Must Go On

Despite obvious success over the past three years, Portugal still faces some unresolved macroeconomic problems, including the availability of financing, red tape, high taxes and regulation, political instability, and the overregulated labor market. Only imrovement in these areas will see the country become radically more competitive, including within the PIGS group (see Table 2), and gradually close the gap in per capita GDP vis-à-vis industrialized countries.

Table 2.Ranking of PIGS Countries and Italy by the Global Competitiveness Index, 2013-2014 (GCI, among 148 states)

| Country | Overall index | Basic indicators | Increased efficiency factors | Innovation factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portugal | 51 | 41 | 46 | 38 |

| Greece | 91 | 88 | 67 | 81 |

| Spain | 35 | 38 | 28 | 32 |

| Ireland | 28 | 33 | 24 | 21 |

| Italy | 49 | 50 | 48 | 30 |

Source: The Global Competitiveness Report 2013–2014. P. 15–17.

As rated by the World Economic Forum, in 2013 and early 2014, Portugal was one of 37 innovation-driven economies as seen through 12 groups of indicators, on par with the average in five groups and lagging behind in the other seven, including in the macroeconomic environment, financial markets, and labor regulation.

In fall 2013, António Pires de Lima, Portugal's new economy minister, set the goal of using the next several years to convert the industrial sector into the country’s main engine of economic development. This updated strategy [5] asserts that Portugal’s attractiveness should improve through increased exports, investment support, moderate consumption growth and better labor quality. This year is expected to see the start of consistent GDP growth to 2.2 percent in 2020, boosting investment and the country’s extended integration into the global economy, with a rise in employment expected from 2015 (see Table 3).

Table 3.Trends in Portugal’s Key Macroeconomic Indicators, percent*

| Indicators | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | -3,2 | -1,8 | +0,8 | +1,5 | +1,7 | +1,8 |

| Private consumption | -5,4 | -2,5 | +0,1 | +0,7 | +0,9 | +1,0 |

| Public consumption | -4,7 | -4,0 | -2,8 | -2,2 | -2,0 | -0,9 |

| Investments | -14,3 | -8,5 | +1,2 | +3,7 | +4,0 | +4,4 |

| Exports | +3,2 | +5,8 | +5,0 | +5,3 | +5,5 | +5,5 |

| Imports | -6,6 | +0,8 | +2,5 | +3,7 | +4,4 | +4,6 |

| Unemployment quota | 15,7 | 17,4 | 17,7 | 17,3 | 16,8 | 16,2 |

| Employment increment | -4,2 | -3,9 | -0,4 | +0,4 | +0,6 | +0,6 |

* 2012 – preliminary data, 2013 – estimate, 2014–2017 – forecast.

Source: Estratégia de Fomento Industrial para o crecimento e o emprego 2014–2020, P. 24 (http://www.portugal.gov.pt/media/1238176/20131112%20me%20efice.pdf)

Reforms Across the PIGS

By early 2014, practically all the PIGS countries had charted some successes in terms of economic reform, including by improving the balance of payments and reducing the budget deficit. Labor expenses fell, the European Commission’s confidence started to rise (see Table 4). At the same time, government bond yields dropped. The European Central Bank’s June 5 decision to cut the interest rate to the historical low of 0.15 percent has bolstered most of these states’ debt securities, with investors’ demand growing and yields plummeting, indicating a significantly wider opening to the international capital markets.

Table 4. Medium-Term Dynamics of Basic Indicators for the PIGS and the Eurozone

| Indicators | Year | Greece | Spain | Ireland | Portugal | Eurozone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Share of budget deficit in GDP, percent | 2009 | -15,7 | -11,1 | -12,4 | -10,2 | -6,4 |

| 2013 | -2,1 | -6,6 | -6,7 | -4,5 | -3,0 | |

| Share of current account deficit in GDP, percent | 2009 | -14,4 | -4,8 | -2,3 | -10,8 | +0,2 |

| 2013 | -2,3 | +1,1 | +7,0 | +0,4 | +2,7 | |

| Economic trust index for European Commission* | 2009 | 74,8 | 73,8 | n/a | 75,4 | 70,1 |

| April 2014 | 95,4 | 101,5 | n/a | 100,6 | 101,5 | |

| Dynamics of labor costs, percent | 2009– 2013 | -15 | -7,6 | -13 | -6.6 | +3,0 |

| OECD employment protection index ** | 2008 | 2,9 | 2,7 | 2,0 | 3,5 | 2,4 |

| 2013 | 2,4 | 2,3 | 2,1 | 2,7 | 2,3 |

*100 percent – average long-term trend; minimum for these countries in 2009; no data available for Ireland.

** The lower the labor regulation level, the lower the index.

Source: http://www.wiwo.de/politik/europa/euro-krise-banco-de-portugal-ist-pessimistisch/9903074.html

Why have these countries joined Portugal in overcoming the crisis phenomena?

Ireland fell victim to the real estate boom propped up by cheap credit at a relatively high inflation rate: in 1996-2006, real estate prices rose by 400 percent. Eventually, though, the bubble burst, with prices dropping dramatically, mortgage securities depreciating, and the entire banking system, in which mortgage credits were as high as 200 billion euro, plunging into an abyss. It got worse due to tangible growth in the budget deficit and sovereign debt. To avoid default, Dublin was the first to apply for international credit, and in late 2010 received 62.5 billion euro, i.e. 17.7 billion euro from the EFSF, 22.5 billion euro from the EFSM, and 22.5 billion euro from the IMF. Another 22.5 billion euro came from other sources).

In exchange, Ireland launched a reform program focused on toughening budget policies that included lowering social expenses and raising taxes. The government increased excise duty but flatly refused to put up corporate income tax (12.5 percent). In 2011-2013, total budget savings reached 13.3 billion euro, and the government managed to cut the budget deficit, stabilize the financial system, normalize the banking sector, and even initiate reforms of the healthcare and pension systems. On December 15, 2013, the country was the first to free itself from foreign credit mechanisms and started developing a medium-term economic plan through 2020 to continue structural reforms and improve economic competitiveness. Notably, Ireland is topping other group members in this area (see Table 2).

Despite obvious success over the past three years, Portugal still faces some unresolved macroeconomic problems, including the availability of financing, red tape, high taxes and regulation, political instability, and the overregulated labor market.

Greece had neither formal nor real grounds for joining the Eurozone, its state debt stood at 104 percent on accession in 2001. By 2009, that figure had climbed to 127.1 percent and by 2011 it had soared to the record high of 165.6 percent. In 2009, the budget deficit stood at 13.6 percent of GDP against the permissible level of three-percent [6], while the costs of refinancing debt on the global markets skyrocketed. Escape from the looming sovereign default came in form of two emergency assistance packages, the first comprising 52.4 billion euro from the EU and 19.1 billion euro from the IMF, and the second – 144.6 billion euro and 19.1 billion euro from the same benefactors, respectively). Along with broad reforms, among them higher VAT and excise duties, lower pensions, modest salary rises, a liberalized labor market, and the cancellation of 13th and 14th salaries for government employees, these measures have brought Greece a portion of orderliness in its economy and finances, although the creditors are closely watching how Greece fulfills its obligations.

Greece is not yet ready to turn its back on foreign crediting. Despite some progress, the reforms lag behind other countries, in part because of resistance from government employees, citizens and private enterprises.

Spain, the largest PIGS economy and the fourth largest in the Eurozone, in 2009 was in debt to the tune of 53 percent of GDP. The calamity stemmed from the astonishing construction boom and related banking crisis, with loans easily extended both to individuals and legal entities. After the real estate sector collapsed, Spanish banks, which had also profusely invested in the Portuguese economy, were in serious trouble. In order to save them, on June 25, 2012, Madrid applied to Brussels for help and on July 20 received approval for a sum of up to 100 billion euro during 18 months. On December 11, 2012, the European Stability Mechanism, set up on November 29, 2012 to succeed the EFSF and EFSM, gave Spain, its first client, the initial tranche of 39.5 billion euro. In contrast to Ireland, Greece and Portugal, where the funds went to the government, in Spain funds flowed to the Fondo de Reestructuracion Ordenada Bancaria (FROB), a special bank-restructuring fund authorized to execute the rehabilitation of credit institutions via the extension of preferential credits. On February 5, 2013, the second tranche of 1.895 billion euro arrived, making a total of 41.5 billion euro. Notably, the assistance program that was set to expire on January 23, 2014 contained no conditions because creditors were impressed by Madrid’s ongoing reforms.

Along with bank rehabilitation, the government continued consolidating the state budget and introducing strict reforms, of a kind not seen for the past 30 years, against the backdrop of an extremely depressed labor market, with overall unemployment at 25 percent and that for young people reaching 55 percent. These reforms were accompanied by sequestering government expenditure, including healthcare and education, an eight-percent salary cut for government employees, a 25-percent reduction in government agencies’ budgets, frozen pensions, closure and privatization of some state enterprises, and higher taxes. Liberalization of the labor market delivered a simplified hire-and-fire procedure and gave employers the right to impose involuntary transfer and pay cuts with no need to listen to labor unions. Following the German example, the Spanish introduced mini jobs and a “dual” education system combining numerous practical apprenticeships with classroom studies. The establishment of new enterprises has become easier, with tax breaks for new entrepreneurs.

Over time, the anti-crisis measures brought fruit: the banking system stabilized, the state budget deficit substantially reduced and labor costs shrunk, while labor efficiency and purchasing power rose. Spain was exporting more cars, industrial equipment, foods, garments and services (including construction). Tourism also came back to life, with a record-high 60.6 million vacationers visiting the country in 2013. In the third and fourth quarters of 2014, economic growth, although feeble, returned. Spain’s Economy Minister Louis de Guindos predicted that in 2014 GDP growth should reach 1.2 percent, in 2015 – 1.8 percent, and in 2017 – 2.8 percent. In 2014, hitherto soaring unemployment is expected to fall by 0.6 percent; in 2015 – by 1.2 percent; and in 2016 – by 1.5 percent, although in the medium term the labor market is likely to remain Spain’s weakest link.

These countries have returned to the international capital markets, their common problem remains substantial indebtedness of corporations and households.

In November 2013, the government chose to refrain from extending the credit line, and in January 2014 the program expired. For a complete recovery, Spain needs more structural reform and economic modernization, an improved innovations sector and greater competitiveness. For now, Mariano Rajoy’s government, wary of the opposition and electorate, is sticking to cautious statements avoiding any long-term economic strategy.

Prospects

As the sovereign financial crisis and lower international ratings barred the PIGS from servicing their state debts, their gradual recovery from this catastrophic decline was only possible thanks to external credit lines provided by the European Union and the IMF. Except for Spain, assistance hinged on sweeping reforms, mostly aimed at consistent budget consolidation through curtailing spending and hiking taxes, which were developed and strictly monitored by the creditors. Along with the liberalized labor market, entrepreneurship assistance, rehabilitation/stabilization of banking, lower labor costs, and pension and taxation reforms, by 2013 these measures slashed budget deficits and generated grounds for gradual recovery, with growing exports and domestic consumption also doing their bit. Payback came in the form of thousands of closed enterprises, rising joblessness and an increasingly frustrated electorate.

However, this seems to have been only the initial stage, possibly the hardest, on the road to recovery and renewed competitiveness, as the governments now face further large-scale structural changes, still likely to be largely financed by EU mechanisms, although cautious optimism would indicate they might be in a position to go it alone.

While Portugal boasts a clear-cut long-term strategy for restructuring its economy and Ireland seems to have an integrated vision of the way ahead, Spain has been reluctant go beyond general statements and declarations, although the government appears to demonstrate both the will and the readiness to continue reforms and is planning further measures, including reducing the tax burden on companies and individuals. These countries have returned to the international capital markets, their common problem remains substantial indebtedness of corporations and households. Greece, still protected and monitored by foreign creditors, is recovering but still presents the weakest link in the Eurozone.

In future, though, the abbreviation PIGS is not likely to once again be synonymous with the Eurozone’s woes.

1. The PIGS group comprises Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain.

2. An Integrated Analysis of Causes for the Eurozone Crisis. See: Butorina O.V. The Eurozone in Crisis: Errors or Pattern? // Modern Europe. 2012. № 2. Pp. 82–94.

3. Portugal: From Revolution to… // Ed. by V.L. Vedernikiv. Moscow: Ves’ Mir Publishers, 2014.

4. Experts believe the country may reach the Maastricht sovereign debt criteria, i.e. under 60 percent of the GDP, only by 2030.

5. Estratégia para o Crecimento, Emprego e Fomento Industrial, 2013–2020, the basic plan had been made public by Álvaro Santos Pereira, the previous economy minister, in April 2014, and the amended version titled Estratégia de Fomento Industrial para o crecimento e o emprego 2014–2020 (http://www.portugal.gov.pt/media/1238176/20131112%20me%20efice.pdf).

6. Butorina O.V. Ibid. Pp. 87–88.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |