Latin America and the Caribbean Development Forecast until 2020

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Scientific Director of the RAS Institute of Latin America, RAS Corresponding Member

Over the last two decades the region as a whole has undergone a number of major shifts. Beginning in 1980, a wave of democratization put an end to the period of military dictatorships. As a result of the growing costs caused by neo-liberal reforms starting in the late 1990s, crises have swept traditional political parties out of power and facilitated the rise of alternative movements and leaders. This so-called “left drift” has ushered in a wider range of political regimes that includes governments located at the center of the political spectrum as well as those on its left radical flank.

Authors: Vladimir Davydov, Alexander Bobrovnikov, Boris Martynov, RAS Institute of Latin America

1. Basic characteristics

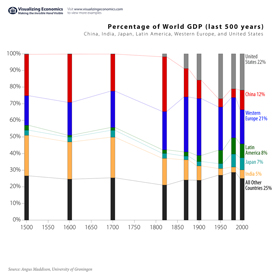

According to regional indicators, the Latin America and the Caribbean falls into the “middle category” in the world rankings of economic development. Accounting for 15% of its landmass and representing 8.5% of the world’s population, the Latin America and the Caribbean is also responsible for 6.2% of aggregate world product in nominal terms in 2007 or 8.3% of GDP when measured as PPP. Its contribution to the global volume of industrial production amounts to 8.2%, while it contributes 13% of agricultural production and 5.5% in total world exports [1].

The gap separating the upper echelon of countries in the region from the industrialized countries (2.0-2.3 times per capita GDP as PPP) is substantially smaller than that which separates the upper and lower tiers of the Latin America and the Caribbean (15-16 times per capita GDP as PPP). Further separation is more apparent and ongoing. Most of the countries in the region have established modern institutional structures with truly representative democratic principles, strong levels of state governance, and market economies. Beginning in the last century, these countries have also been actively engaged in joining the networked economy and developing information-based societies.

Yet some aspects concerning their peripheral involvement in global economic relations are still problematic (especially, as far as the least developed countries of the region are concerned). Therefore, the issue of a new stage in modernization and competing economically on a global scale has become a central goal for Latin America and the Caribbean countries in the period leading up to 2020. The low level of export diversification, which has been noted not only in the small countries but also in the medium-sized states (such as Venezuela and Chile), continues to be another impediment along the way towards modernization. The three groups of traditional commodities (energy, metals, and food products), account for 56-90% of the total value of export in the above-mentioned countries, unlike a total of 16.5% in Brazil, 25.9% in Argentina and 26.7% in Mexico [2].

Over the last two decades the region as a whole has undergone a number of major shifts. Beginning in 1980, a wave of democratization put an end to the period of military dictatorships. Most of the countries in that region also underwent neo-liberal reforms in the 1990s. During the period prior to “the Asian crisis” in 1997, these reforms help to create relative macroeconomic stabilization, reduce national budget deficits, install greater fiscal discipline, increase the influx of foreign capital, and intensify foreign trade relations. However, the neo-liberal experiment also heightened the vulnerability of national economies to external shocks and weakened mechanisms of economic security. Moreover, they have been associated with major social costs.

As a result of the growing costs caused by these neo-liberal reforms starting in the late 1990s, crises have swept traditional political parties out of power and facilitated the rise of alternative movements and leaders. This so-called “left drift” has ushered in a wider range of political regimes that includes governments located at the center of the political spectrum as well as those on its left radical flank.

The region was not left behind in the ‘information revolution’, as evidenced by the intense development of telecommunication infrastructure and application of industrial and administrative innovations. This wave of modernization has taken several forms: from attempts to establish self-sufficiency and self-reliance on the domestic market (Brazil), to claiming specific segments of the market for services (Chile), to taking advantage of the global division of labor (Mexico), and to even catering to one major transnational corporation (Intel, as in the case of Costa Rica).

The gap separating the upper echelon of countries in the region from the industrialized countries (2.0-2.3 times per capita GDP as PPP) is substantially smaller than that which separates the upper and lower tiers of the Latin America and the Caribbean (15-16 times per capita GDP as PPP).

By and large, these scenarios remain in force when the modern industrial sector of the economy continues to be focused on servicing external industrial networks. Labour productivity and progress in scientific and technological spheres continue to substantially lag behind industrialized countries. Brazil is perhaps considered the only exception in a number of sectors.

The situation of quasi-unipolarity in the 1990s had also its repercussions for Latin America. The “hard power policy” implemented by the U.S. provoked negative reactions in public opinion in Latin America and the Caribbean by reviving and intensifying anti-American feelings which clearly surfaced during the second term of the George W. Bush administration. Recently, political and economic elites in Latin America and the Caribbean countries have begun to be more proactive in responding to changes in the division of power on the world stage, to slowing economic growth and the relative limitation of US geopolitical influence, and to the strengthening of other centers of power (including the EU and China). The foreign policies of Latin American states have relied more intensively on new orientations, helped by a period of growth in their economies and relative welfare over the years of 2002-2007. Over the course of this “left drift,” the functions of the state have been partially reconstituted along with a more active role being created for it in regulating the economy and charting a more independent foreign policy course to correct the distortions caused by the neo-liberal reforms.

Three main factors have had an impact on the foreign economic policies of countries in the region. The first factor is related to accelerating shifts in the distribution of power on the world stage against the backdrop of apparent shifts in growth centers from the North Atlantic area to the Asia-Pacific region. The second factor involves the increasing role of major developing economies (such as Brazil and Mexico) and their search for a more balanced world financial and economic architecture. The third factor is connected to the emergence of new coalitions and changes in the configuration of the existing international coalitions to include the participation of developing countries, such as the Latin America and the Caribbean states. Along the same lines, it is important to acknowledge the new round of regional economic integration within the Latin America and the Caribbean which has produced the Union of South American Nations — UNASUR and the establishment of a number of other institutions (including ALBA, Banco del Sur and South American Defense Council — SADC) and a regrouping in other traditional associations as well.

The “hard power policy” implemented by the U.S. provoked negative reactions in public opinion in Latin America and the Caribbean by reviving and intensifying anti-American feelings which clearly surfaced during the second term of the George W. Bush administration.

At the same time, the two major countries in the region, Brazil and Mexico, have continued their upswing. Currently they account for 4.5% of the world population, 4.1% of the world GDP and 3.1% of the world trade, i.e. from one half to two-thirds of the aggregate output of the Latin America and the Caribbean region. In the 2000s when the position of the US in the region began to slightly decline, especially after the failure of the Inter-American Zone of Free Trade (2005), Brazil actually began to play the role of the second center of power on the continent.

2. Strategic Priorities

The political objectives of the governments of individual countries vary significantly and depend on structural conditions and the specific issues being addressed. However, both at the national and regional level, there is an impression that modernization requires strategic planning based on the results of long-term development forecasts and supported by the development of special innovation programs or important segments of the national economy [3]. The overall principles for these strategic initiatives have been formulated in one of the recent reports by the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) [4]. In Mexico, the correction of the strategic course has been carried out by the Calderon government after the national discussion entitled “Vision of 2030; the Mexico We Want to See” (2006-2007) [5]. Almost at the same time, experts from the Getúlio Vargas Foundation and Ernst and Young have jointly prepared a series of forecasts for 2030 under the title of “Sustainable Development of Brazil” [6]. In practice, the Lula government has been engaged in a continuous adjustment of eleven clusters of strategic objectives as well as 3,000 national long-term programs amidst annual budgets and five-year indicative development plans [7]. In Chile, state-run organizations carry out about 100 programs and development projects, while in Mexico, similar institutions are responsible for about 150 more. After getting through the worst economic crisis of the early part of the 21st century, Argentina in 2003 developed a strategy of modernization based on scientific research called “The Main Areas of Policy to Form New Sources of the Economic Growth” (2003) [8].

Evgeny Astakhov:

Map of Latin America in the twenty-second

century

The main strategic imperatives for the next two decades are as follows:

1. Policies for effectively transforming industrial sectors by developing technology, increasing labor productivity, fostering the accumulation of human capital and reducing wage inequality.

2. Implementation of a strategy for economic development and modernization by strengthening democracy and public consensus with regards to greater equality (gender, racial, minority, etc.) and “social convergence” with a final goal of building modern civil society on the principles of transparency, national dialogue and guarantees for human rights.

3. Targeted national policies in the innovation sphere to expand the participation of the private sector in financing innovations and ensuring the technical modernization of mineral processing sectors (very important for countries in the region), and to create effective incentives for high-technology industries, so as to avoid falling behind in international markets. At the same time, achieving systematic competitiveness cannot be based on the directly replicating the path to modernization undertaken by other countries and implies adapting processes to local conditions with a view towards history, culture, and the institutional and political characteristics of the region.

4. A choice in favor of a more pragmatic technological policy to ensure stronger national innovation systems and closer cooperation among enterprises, their suppliers and customers, universities, state and private research organizations and financial institutions.

5. Policies towards elaborating and implementing a sustainable long-term development strategy, targeted at facilitating the “comprehensive participation” and building of alliances between the public and private sectors in order to ensure their independence from the cycles of political turnover in individual states.

6. A choice to give the government the authority to select priority sectors (enterprises, sectors, regions, institutions and categories of workers) and control the financing of relevant programs. This choice should be flexible and should react promptly to current changes in the development of technologies and market regulations.

7. An understanding of the need to upgrade “human capital” and develop a modern system of professional training; to carry out a full transformation of education system, consistent with the requirements of high-performance jobs and the principle of equal access of the population to quality education. Moreover, policies are being developed to actively integrate information and telecommunication technologies into education systems, to make computer literacy and Internet communication skills an indispensable condition for higher school education and for decent employment in the labor market, and to ensure wider participation of universities in research and development.

8. Assistance towards quality and open social security for citizens, with guarantees of its democratic and decentralized character by establishing a modern system of public health and sanitation in line with international regulations.

9. Environmental policies closely linked to economic development in a number of areas: the active role the Latin America and the Caribbean countries in various international forums (UN, WTO, EU, etc.) on environmental issues; the implementation of several measures (including tax breaks and state subsidies) to prevent environmental degradation as a result of industrial activities; and mutually binding arrangements between the state and the private sector to share responsibility and criteria for environmental assessment.

10. Modernization of basic economic and social institutions in order to ensure greater competitiveness in the global economy. Institutional reforms should be carried out in accordance with global best practices, but also be based on principles of social equality with a view to overcome the de-facto “exclusion” of strata, social groups or territories from society.

11. Deepening processes of regional integration in order to benefit from trade liberalization and at the same time neutralize the effects of the hyper-segmentation of global and regional markets and the excessive fragmentation the international industrial chain of production. The new integration, in the spirit of open rationalism, should on the one hand strengthen the institutional basis for the existing regional groupings, help elaborate clearly defined norms of their activities, establish the mechanisms to overcome asymmetry and provide compensation in favor of less developed participants, as well as contribute to export diversification and the development of small and medium-size enterprises. On the other hand, it should ensure further integration in services, infrastructure, state procurement and innovation sectors [9].

3. Prospects up to 2020

GDP Growth Rates. A slowdown should be expected up until the year 2015 in the average annual surplus of regional GDP, calculated at a decrease of 2.5-2.9% compared to the previous decade. As the consequences of the recent world crisis, average annual GDP rates in 2015-2020 may reach 3.5-3.7%. One can assume that these indicators will average 3.0-3.5% in the first decade and 4-4.5% in the one following.

The investment rate shall gradually increase to a level of 23-24% of GDP by the beginning of the second decade. During the first ten years, inertia in development progress will set in, whilst in the second decade, a noticeable reinforcement of intensive factors should be expected that will have increase labor productivity.

We assume that by 2020, the level of urbanization will reach 78% as compared to a previous measure of 70% in 1990, which will put the Latin America and the Caribbean on par with currently industrialized countries according to this indicator.

Demography and Labor Market. By 2033, the region will host a population of 700 million people. Urbanization will continue due to the migration of the rural population to major cities accompanied by an exacerbation of environmental, sanitation and utility problems. We assume that by 2020, the level of urbanization will reach 78% as compared to a previous measure of 70% in 1990, which will put the Latin America and the Caribbean on par with currently industrialized countries according to this indicator.

Internal regional differences will be determined by the fact that the area of the Southern Cone (Argentina, Uruguay, Chile and southern states of Brazil) will soon transfer over to the European model of demographic reproduction. In the Andean, Central American and Caribbean parts of the region, as well as in the north and northeast of Brazil, a slowly fading model characterized by high natality will remain. Average population growth in the Latin America and the Caribbean will exhibit a decrease from 1.3% in 2005-2010 to approximately 1% in the first forecast decade and 0.7-0.8% in the second.

The labor market will be influenced by numerous members of younger generations reaching the active working age. In other words, during the next 10-15 years, the active working population will grow at an accelerating rate. At the same time, a slowing down in demographic growth will reduce the economic burden on the employed.

The Latin American labor market will acquire greater flexibility (including the introduction of temporary patterns of employment). This will lead to a further weakening of traditional trade unions and an increase in the role of individual contracts and government policy toward signing “social pacts”. The issue of intercontinental and internal migration will also become important. Donor countries (Mexico, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Salvador, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador) and recipient countries (Argentina and Brazil along with Costa Rica, Chile and Panama) will confront a number of specific problems. It is possible that emigration to the US, Canada, Spain and other industrialized countries will remain at the high level due the growing outflow of qualified specialists. It is important to note, for example, that the total number of highly qualified migrants from the LCA residing in OECD countries increased from 1.9 million people in 1990 to 4.9 million in 2007.

Countries in the region are gradually transforming from a source of basic natural resources to a place for lower or middle “stages” of industrial systems. If in the first decade, China and other South-East Asia exporters retain competitive advantages based on cheap labor advantages, Latin America and the Caribbean countries will become more attractive during the second decade due to low transportation costs, decreased labor costs and an improved investment climate. Overall world ratings will see a slight increase, first of all thanks to Brazil and Mexico. On the eve of the first and the second decade, the most important shift will be a transition of a long-term trend towards reducing the regional quota in the world trade in goods and services. By the end of the forecast period, this indicator (that earlier lagged behind) may equal the share of the region in the global GDP.

Rising energy prices on international markets, difficulties in exploring new deposits (territorially remote areas, deep sea drilling, etc.), and growing demand in the region will compel Latin America and the Caribbean countries to seriously consider alternative sources of energy.

We should expect that the role of modern agribusiness will grow, first of all, in subtropical areas and moderate climate zones (such as the Southern Cone). Already, between 1995-2007 the share of Latin America and the Caribbean in the global agricultural market increased from 11.0 to 13.7%. By the end of the forecast period, Latin America and the Caribbean’s share may exceed 15%. The geography of food exports from the region should expand taking into account growing requirements from not only East Asian countries, but from a number of African countries as well as the countries from the Middle East. Since raw materials located in the Latin America and the Caribbean are increasing in demand by the growing economies of Asia, food exports, as well as those of ore concentrates, metal by-products, and energy products will continue to grow. In particular, China will most actively exploit this new supply corridor, accompanying its purchases with large-scale investments in the industrial capacity of the Latin America and the Caribbean.

At the same time, manufacturing sectors will improve in the Latin America and the Caribbean. The main trend will be towards a significant improvement of traditional sectors. Progress in a number of manufacturing will be determined by changes in the structure of foreign demand and the development of Latin America and the Caribbean domestic markets. As a result, the degree of its “localization” will grow alongside the share of national components in the final product. The share of processed products supplied to the U.S. will slightly decrease in relative (but not absolute) terms and the share of supplies inside the region and other foreign markets may increase. In particular, it is quite possible that Brazil’s continued cooperation with Portuguese-speaking countries (Angola and Mozambique) and other African countries (South Africa and Namibia) will improve. Even Mexico can partially reorient its supplies from the “maquiladoras” that were earlier oriented exclusively to the North American market, to the domestic market, and to the markets of other Latin America and the Caribbean countries.

Notable improvements can be expected in the development of the service sector. Meanwhile, certain traditional LCA services will relatively shrink (such as the informal segment of retail trade), while the modern services sector will grow. Outsourcing, leasing and other business services will be widely expanded.

The tourist sector will continue to grow. Current tourist flows may substantially change, diversifying thanks to tourists from Asia and Europe. The most notable changes will take place in energy and infrastructure. The development of new infrastructure will be influenced by the establishment of Trans-Andean (Latitude) Transportation corridors and the potential construction of a pipeline network, such as the creation of a longitudinal Atlantic-Pacific Network (the Venezuela-Argentina-Peru-Chile corridor). All of this will increase the potential for internal regional trade in energy products (such as oil and gas).

Rising energy prices on international markets, difficulties in exploring new deposits (territorially remote areas, deep sea drilling, etc.), and growing demand in the region will compel Latin America and the Caribbean countries to seriously consider alternative sources of energy. Large-scale exploration of alternative sources of energy will begin in the second decade, primarily in countries with an energy deficit (such as Chile), while Brazil, Argentina and Mexico will already possess resource capacities and the first nuclear power plants. Venezuela and Chile may follow the prospect of developing nuclear energy (but this outcome is more likely in the second decade). Undoubtedly, the region possesses great natural potential in solar and wind power (first of all, Brazil), geothermal energy (Mexico and Nicaragua), as well as bio-energy (most of the countries in the region). Taking into account rugged natural terrain and territorial remoteness, Latin America and the Caribbean countries are also interested in the wider use of mini-power plants. All of this opens additional possibilities for partnership between Russia and Latin America.

The use of natural resources. Taking into account the interests of a larger number of partners outside the region in the supply of raw material and food commodities, relevant niches in global markets will probably expand for Latin American exports.

During the first decade of the forecast period, demand for primary commodities will probably grow as the world economy recovers after the recent global crisis. Furthermore, demand for food products will grow more intensively, with a slowdown in mineral resources, in particular, due to progress in resource saving and the expansion of the use of alternative sources of energy. The high resource capacity of the region will attract actors from outside the region and create renewed competition for Latin American markets.

Environmental issues. The amount of attention paid to environmental issues in the LCA is determined by three factors. First, a significant part of the population lives in major cities where water supply, sanitation and other environmental issues are very acute. Second, foreign corporations during the 20th century extracted mineral resources without making substantial expenditures on environment protection.

Finally, a significant part of the region is located in regions with a high risk of natural disasters and tectonic activity. Environmental monitoring, programs for environmental protection and preservation of natural biodiversity, as well as preventive measures for natural disaster relief will become important areas of national policy, at least in the major countries of the Latin America and the Caribbean. However, major spending on environmental issues and increased preparedness for natural disasters should be expected not earlier before the beginning of the second decade.

The ability to approximate the level of scientific and technological capacity in the industrialized West will be felt only in Brazil and to a lesser extent in a small group of other countries — Mexico, Chile and Argentina.

Innovation. In the more advanced parts of the region, interest will grow in the deployment of TNC industrial capacities in sectors with average level of technological complexity. Taking into account the fact that Latin America and the Caribbean countries have already begun a new round of modernization that will requires the mobilization of domestic resources and the large-scale leverage of foreign capital, the process of economic diversification among the countries of the region will increase.

However, the second wave of technological modernization will encompass a wider number of countries and leave behind the least developed ones.

The ability to approximate the level of scientific and technological capacity in the industrialized West will be felt only in Brazil and to a lesser extent in a small group of other countries — Mexico, Chile and Argentina. Because of the limited resources allocated to R&D, the practice of importing technological advances will prevail. In the majority of the other countries, technological progress will predominantly happen only in isolated pockets and will be targeted at including specific areas in industrial networks established by the TNC.

The advance and diffusion of new technological systems associated with a comprehensive development of a number of promising technologies (nanotechnology, biotechnology, robotics and alternative energy) in the modern electronic network format will only occur in the leading echelon of Latin America and the Caribbean countries. Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Columbia and Chile will all undergo certain structural readjustments in their economies. However, this process will develop only moderately quickly. Its acceleration will require a substantial increase in saving rates.

Economic policy, public sector and private business. Governments will need to develop a new system of relations with private business actors. On the one hand, this is determined by the overall aggravation of problems of governance in Latin American society, and, on the other, by continuing transformation of the private sector. Practically, we should expect that the forms and mechanisms of the public-private partnership will diversify: concessions, public lending guarantees, co-financing of major projects (first of all infrastructural), etc. Under these circumstances, national development banks will preserve their role in most of the countries and remain an important instrument for addressing the most complex problems.

In the Caribbean, the process of differentiation will develop even more intensively than on the continent. Relatively prosperous countries and territories with high living standards that have managed to find their niche in the world economy have already been singled out as a separate group of interest (Bahamas, Barbados and Virgin Islands).

Differentiation of the countries of the region. The countries of the Southern Cone — Chile, Argentine, Uruguay and Brazil — have the best chances to realize their economic potential by taking advantage of internal political stability. Brazil will continue its transformation from a regional into a global player. Economic instability and political turbulence will persist in the Andean zone (Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru, Columbia and Venezuela), along with Paraguay. Colombia may become an exception only if it manages to make progress in solving domestic conflicts and curtailing drug trafficking. Possible aggravation of domestic ethnic conflicts in Peru and Bolivia may be connected to growing gaps in living standards between different regions. Political volatility in the Andean countries may be quite substantial. Mexico’s orientation towards the U.S. market and the rapidly increasing coordination in economic dynamics between the two countries will make Mexico more dependent on the development in the economy of its northern neighbor. Political instability and the recent outburst of crime in Mexico will not contribute to the rapid normalization of the overall situation in that country. Only by the end of the next decade may Mexico re-establish its influence in the region.

Central America (except for Costa Rica) is extremely vulnerable in social and political terms. The specific situation in individual countries will be determined by a contradictory combination of factors related, on the one hand, to the degree of integration in the global division of labor (following the Mexican model) and on the other, to growing disparities in the national economy and limited opportunities for real progress in addressing social problems and undertaking economic modernization.

In the Caribbean, the process of differentiation will develop even more intensively than on the continent. Relatively prosperous countries and territories with high living standards that have managed to find their niche in the world economy have already been singled out as a separate group of interest (Bahamas, Barbados and Virgin Islands). But some of these who opted for offshore businesses will experience serious difficulties due to the desire of the US and other major economies to limit this practice. Choices for new specializations for these island mini-states are extremely limited.

Cuba’s trajectory will be associated with a gradual transformation of the country similar in some respects to the Vietnamese path and summarized as a conservation of the basic elements of the political system with certain liberalizations in the economy. The sustainability of the former system of power in Cuba depends very much on the durability of the union of the left-radical regimes (the ALBA that includes Bolivia, Venezuela, Dominica, Nicaragua, Cuba and Ecuador). Realistically there are no grounds for an over exaggerated assessment of changes in the Latin America and the Caribbean rating within the world economy. A more optimistic forecast by the end of the second decade of the 21st century might be made for individual and biggest countries of the Latin America and the Caribbean, in particular Brazil and Mexico. But by and large, the region will continue to lag behind the “Asian dragons” and other rapidly growing “emerging markets”.

Income level and reduction of poverty. By the end of the forecast period, significant shifts will take place in the social sphere. Stable economic growth by 2020 will allow for significant increases in income for the majority of the population. Many of the Latin America and the Caribbean countries will achieve significant successes in consolidating their market economy and establishing regulatory mechanisms.

Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Colombia and Chile will approach in various degrees countries with an average level of income. Accordingly, the size of the middle class will expand. Notable progress in the fields of education, public health and social security may be achieved within the framework of socially oriented policies.

Unlike the Old World, Latin America does not possess fertile soil for inter-civilizational or religious clashes and few of the prerequisites for trans-border terrorism.

As for politics, the positions of centrist forces will gradually strengthen in the Latin America and the Caribbean countries at the higher or middle level of development. The middle class, which traditionally has acted as a shock absorber against the influence of the extreme flanks of the political spectrum, will provide the basis of support for these forces. The winners of this political competition will be parties and movements that incorporate principles of democracy, economic rationality and social consensus into their activities and ideology.

During the first decade, a reduction in the number of leftist is possible (approximately by one third) though they will not fall completely off political map of the Latin America and the Caribbean. More moderate governments take power, which will pull the political pendulum closer to the center. However, support for the left orientation may grow in the future. More extreme options, such as that in power in Venezuela will become less attractive, as left-oriented regimes move toward more pragmatic policies. These governments will pay attention to the social functions of the state combined with the improvement of institutions and legal entities. Regimes with strong institutions are already in the majority in the region and political instability will be confined to a few places. However, for the forecast period, risks of further problems for UNASUR and other entities of internal regional integration will remain. Low-intensity internal conflicts associated with periodic aggravation of social divisions, ethnic radicalism, and cross-border drug trafficking in some countries will be typical for the period under review. However, unlike the Old World, Latin America does not possess fertile soil for inter-civilizational or religious clashes and few of the prerequisites for trans-border terrorism.

4. Foreign Orientation

Positions in the world and diversification of relations outside the region. The position of Latin America and the Caribbean in the international arena will be determined by the expansion and diversification of international cooperation. The scope for maneuvering in the international affairs is growing quickly. Latin America and the Caribbean countries in the first and the second tiers possess an opportunity to go beyond their traditional niche on the periphery. The transformation of external economic ties with the new epicenters of growth is possible along three directions: the share of trade with the US will slightly decrease with a relative increase for the role of the EU; a new spiral of growth in intra-zonal trade is possible; and the positions of Asian countries in the foreign economic ties of the Latin America and the Caribbean will continuously grow. Undoubtedly, Brazil will take the lead by developing ties in several directions — the South, BRICS, and dialogues with the US and EU, whilst Mexico will follow the same track with fewer chances for success. Replacing the previous domination by American strategic interests on the continent, a more balanced policy of cooperation with players outside the region will come into place.

Over the next 20 years, two opposing tendencies will prevail in the Western Hemisphere. On the one hand, there will be a trend towards a regional union, and on the other, a search for new models of engagement consistent with conditions and requirements of each individual group of countries.

Foreign trade and positions at the international markets. During the forecast period, the external sector will continue to exert a strong influence on the volumes of national output and macroeconomic stability despite potential adjustments in the export-oriented model because of a partial re-orientation towards the internal market. The potential growth in demand for a number of important strategic resources (hydro-carbons, other raw materials, as well as food products and water supplies) will be combined with an increasing attractiveness of Latin America and the Caribbean countries that possesses major deposits of raw materials and available arable land for agriculture. The importance of this region as a producer of oil, natural gas, various types of bio-fuel and other alternative energy products, as well as food, may help create growth in the region’s position in the world economy.

Regional integration. The process of developing and consolidating Latin American integration requires at least ten years. Progress is only possible if quality shifts take place in the division of labor within the region on the basis of growth of trade in energy products and food, as well as the deployment of some elements of the industrial network within the region itself and a launching of regional trade in modern services, as well as development of infrastructural integration — the issues to which a particular importance is attached. National authorities with a responsibility of promoting new integration may be established.

Significant arrangements may be achieved in this area.

It is quite possible that trends will develop towards strengthening commercial links between South America and the Asia-Pacific countries and the establishment of the Trans-Pacific integration process based on a complementarity of the economies of the two regions.

One should not exclude either the development of Trans-Atlantic integration on the basis of agreements that have been developed over the past decade to create economic associations such as MERCOSUR, ASN and the Central American Common Market with the EU and CARICOM.

In the Northern zone, the U.S. and its NAFTA

agreement will remain the undisputed leader.

The countries of Central and Caribbean America,

Columbia and Peru will gravitate towards that

group.

Over the next 20 years, two opposing tendencies will prevail in the Western Hemisphere. On the one hand, there will be a trend towards a regional union, and on the other, a search for new models of engagement consistent with conditions and requirements of each individual group of countries. The prospect of unifying all the states in the region into a single integration bloc with NAFTA appears unlikely. Opposition to this project on the part of Brazil, which claims a special role as a regional leader, must be taken into account. There is a certain probability that Latin America and the Caribbean countries will continue to develop a project of regional organization that assume a number of coordinating functions without trying to substitute for the existing OAS.

As far as differentiation is concerned, two main areas of integration will most likely emerge – the North and the South. In the Northern zone, the U.S. and its NAFTA agreement will remain the undisputed leader. The countries of Central and Caribbean America, Columbia and Peru will gravitate towards that group. These countries will build their strategy for participation in globalization first of all by working through the U.S. economy, accepting roles of “younger” partners and take advantage of relative advantages such as geographic proximity to the North American market. Classical forms of integration will develop based on trade liberalization through the framework of CACM and CARICOM and NAFTA. Diversification of foreign economic ties with Europe and the Asia-Pacific will probably work counter to the strengthening of integration with the U.S. economy, which already now accounts for 50% of trade turnover with Central American and Caribbean countries and approximately 80% with Mexico. A different strategy is promoted by Brazil. It is aimed at diversifying external ties, developing cooperation along the South – South line, and counteracting the monopolistic domination of the U.S. on the continent. Aspiring to a status of world power, Brazil believes that it is necessary to assume a leadership position in South America and raise its status in the developing world by positioning itself in international organizations as an advocate and defender of the interests of all developing countries. This will inevitably continue the course that it has followed the last two decades, starting from implementation of MERCOSU, the South American common market (1991), and then by acting as a counterbalance to ALCA, the unification project of 12 South American countries into the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) in 2004, which has been pursuing so far only geopolitical goals.

Taking into account limited economic opportunities in Venezuela, which except for subsidizing oil exports cannot offer much to partner countries, the ALBA strategy will hardly live longer than Hugo Chavez’s term in office.

Recently, Brazil has tried to combine its integration efforts for the Latin American region with a development of extensive intercontinental ties. This has been evidenced by a treaty on a strategic partnership with the EU, the establishment of IBSA (India, Brazil and South Africa association) in 2003, and active participation in the BRIC project. Trade integration in the Southern zone will develop slower than in the North as a result of a low level of complementarity in economic entities, the weak development of transportation and telecommunications, limited opportunities in Brazil’s domestic market, the weakening of traditional integration groupings (especially the Andean community of nations) and the potential aggravation of ideological, political and economic differences among the countries of the region.

Under these circumstances, the deepening of integration and the development of a free trade zone will confront difficulties in the future. Therefore, it is to be expected that various types of cooperation will develop in more or less flexible forms that do not require rigid discipline and or the participation of a large number of countries. Promising areas include the development of transportation systems, telecommunications, energy, and the promotion of trade, as well as addressing environmental problems.

The prospects for the Bolivarian Initiative for Latin America (ALBA) [10] do not seem to be bright. Taking into account limited economic opportunities in Venezuela, which except for subsidizing oil exports cannot offer much to partner countries, the ALBA strategy will hardly live longer than Hugo Chavez’s term in office.

Russia – Latin American relations. Over the period of 2010 – 2020, mutual interest in the expansion of business ties will grow. Growth in trade turnover will be accompanied by diversification in commodity structures and the expansion of the bready of Russian commodity supplies, including the intensification of cooperation in investment activity: hydropower and nuclear energy, the exploration and production of natural resources, railway construction, aerospace sector, construction and operation of oil and gas pipelines, and some areas of telecommunications. The remaining relative competitiveness of Russia in these sectors along with the growing resource requirements of Latin America and the Caribbean countries should bring about increased scope in this interaction. In the area of scientific and technological cooperation, the use of renewable sources of energy, bio- and nanotechnologies, as well as the production of composite materials will continue to develop.

We should expect that military and technical cooperation will remain at current levels. However, the state of the Russian economy and problems with innovation and technological adaption (especially the engineering sector) will not allow enable it to fully diversify its exports through increased supplies of machines and equipment. It is to be expected that the deficit of Russian trade with Latin American countries will continue. Russia will hardly rank among the priority partners of the Latin America and the Caribbean countries, but can achieve solid positions on individual markets of the region, such as Brazil.

It is to be expected that the deficit of Russian trade with Latin American countries will continue. Russia will hardly rank among the priority partners of the Latin America and the Caribbean countries, but can achieve solid positions on individual markets of the region, such as Brazil.

Russian businesses will be limited by intensifying competition from local firms and companies, who have strengthened their industrial and technological potential and are able to provide high technology services in such areas as hydropower, telecommunications, manufacturing, the production of agricultural tools etc. One should not ignore either growing competition from China.

In order to better take advantage of existing opportunities, the following four sets of problems must be solved:

- A common approach to cooperation. Russia needs to take into account the increased economic potential of Latin America and the Caribbean countries, which are growing in their capacity as exporters of machines and equipment and a source for direct investments. The time is ripe to begin a targeted policy to improve Russia’s image among the populations of Latin American countries by using the wide opportunities presented by modern information technologies.

- The improvement of legal and financial support envisages the expansion of the legal and contractual basis, including the signing of agreements on mutual protection of investments and avoidance of double taxation, modernization of credit and fiscal practice and solutions for the problems of credit and financial support of export-import operations and mutual investment projects.

- State support should be aimed at removing interagency barriers and establishing a common mechanism for interaction between various types of foreign economic activity. The practice of state guarantees should expand to the implementation of the most promising investment projects for Russia. The state must also promote contacts among small- and medium-size businesses of Russia and relevant Latin American countries which participate in foreign economic activity.

- Change in the format of relations. It is advisable to intensify the political and diplomatic presence of Russia (in some cases, if only as an observer) in the key international organizations of the Latin America and the Caribbean and the Western hemisphere. It is necessary to expand cooperation with regional economic groupings, solve problems of Russia’s accession to the Inter-American Development Bank and sign cooperation agreements with sub-regional lending and financial institutions. Trade and economic cooperation with the most promising partners (Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina) should be transformed into free trade agreements by the end of the first decade.

Notes

1. Estimate by the World Bank. World Development Indicators, 2009. P. 208-210, 216-218.

2. Estimate by CEPAL. Anuario estadistico de America Latina y el Caribe, 2008. Santiago de Chile, 2009. P.196-218.

3. Typical examples are the Mexican program in the area of information and telecommunication technologies (Vision Mexico 2020. Politicas publicas en material de Technologias de Informacion y Comunicaciones para impulsar la competitividad de Mexico) or the Brazilian program in the area of energy (WWF-Brazil. Sustainable power sector. Vision 2020).

4. Cf: CEPAL. La transformacion productive 20 anos despues . Viejos problemas, nuevos oportunidades. Santiago de Chile, 2008.

5. Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Vision 2030. El Mexico que queremos. Mexico: Presidencia de la Republica, 2007

6. Sustainable Brazil. Economic growth and consumption potential. Sao Paulo, EYGM Limited, 2008; Sustainable Brazil. Horizons of Industrial Competitiveness. Sao Paulo, EYGM Limited, 2008.

7. Brasil. Ministerio de Planejamento. Plano Plurianual, 2008-2011. Vol. I Brasilia, 2007. P.40-42.

8. Componentes macroeconomicos, sectorales y microeconomicos para una strategia nacional de desarollo. Lineamentos para fortalecer las Fuentes del crecimiento economico. Buenos Aires, 2003.

9. Compiled on the basis of data: CEPAL. La transformacion productive 20 anos despues . Op.cit. P. 317-328; Brasil. Ministerio de Planejamento. Plano Plurianual, 2008-2011. Op. Cit. P.40-55; Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Vision 2030. El Mexico que queremos. Op. cit. P. 23-27; CEPAL. La proteccion social de cara al futuro: Accesso, financiamento y solidaridad. Montevideo, 2006.P 77-111, 149-180; CEPAL. Desarrollo productivo en economias abiertas. Santiago de Chile, 2004. P 123-128, 163-169,209, 235-236, 260, 326, 350-351, 373, 386-387.

10. The ALBA includes Venezuela, Bolivia, Honduras, Cuba, Nicaragua, Ecuador and three small island states of the Caribbean.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |