As the Cold War drew to a close, the Asia-Pacific has essentially become a region of U.S. maritime dominance — a situation Australia was totally comfortable with, given the elaborate security alignment the United States and Australia have. But then China started to rise and demonstrate more and more assertiveness, aspiring to take its place in the Asian maritime balance of power. The Australian leadership is now seeking a truly multipolar architecture for Asia, one including all resident powers.

This year’s Shangri-La Dialogue clearly showed that Asia has not become safer over the last year and is unlikely to become any safer in the near future. Quite the contrary, the security threats at hand may well extend far into the next decades, making the Asian Century not one of economic dynamism, but of political squabbles.

Just this week, a high-level team of scholars, former diplomats, and intelligence officers from the Australian National University visited Moscow and held meetings with think-tanks, government agencies, and media — a Track 1.5 engagement not seen in a long time. The two countries are not on the best terms these days, with bitter manifestations from the infamous “shirt-fronting” threat by then-Prime Minister Tony Abbott to actual economic sanctions arranged by the United States and EU and joined by Australia.

However, as the Track 1.5 discussions in Moscow went on, the unlikeliness of Russia-Australia strategic interaction went from natural to regretful. The two countries enclose the vast strip of land and sea which is the Western Pacific in its two extremities — Russia from the north and Australia from the south. And though the heartland — or, more accurately, the heartsea — of this region is the East and South China Seas, the two countries are essential as the strategic rearguards of security and thus prosperity in Asia.

For Australian foreign policy, there is even a clearer interest in Russia. As the Cold War drew to a close, the Asia-Pacific has essentially become a region of U.S. maritime dominance — a situation Australia was totally comfortable with, given the elaborate security alignment the United States and Australia have. But then China started to rise and demonstrate more and more assertiveness, aspiring to take its place in the Asian maritime balance of power. Recognizing this not as a fluke, but a long-term trend, the Australian leadership is now seeking a truly multipolar architecture for Asia, one including all resident powers.

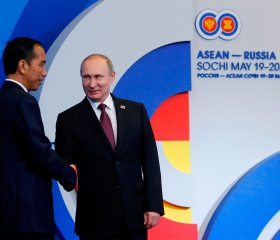

As Russia is demonstrating more and more interest in holding a stake in regional security and trying to develop meaningful relationships not only with China, but also Japan, South Korea, India, and ASEAN, the moment seems right to incorporate Russia into Australia’s vision of regional multipolarity.

Still, it will not be easy for Russia to join the efforts of creating a regional security system.

First, Russia is still a newcomer in terms of economic presence. Moscow missed 20 years of economic integration; its businesses are not well familiar with Asian markets; and its economic policies were never aimed eastward in modern history. All of this means that Russia lacks the indispensability that would guarantee it a seat at the table.

Second, some regional players, including Australia, consider Russia’s conduct elsewhere to have breached trust, rendering it almost a castaway. Moreover, now that Russia is building closer ties to China those concerned by Beijing’s behavior believe that China may use its newfound influence on Russia and coerce it to support China in the South China Sea. The way Chinese media and spokespeople interpret Moscow’s opposition to the internationalization of territorial disputes lends a good argument to those sharing such fears.

Third, Russia has yet to present an elaborate version of its vision of the regional order. Officials call for one that is multilateral, inclusive, and based on equality, respect, and international law. Apart from the clear dislike of the U.S. alliance network, these suggestions are no more concrete that Australia’s “rules-based” order or U.S. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter’s “principled community.” The way UNCLOS is not helping to resolve the South China Sea disputes goes to show how little rules, laws, norms, and principles can actually do now.

This may actually make Russia a more significant player in the Asian power balance. Moscow’s strong focus on sovereignty will make it unlikely to fall under too much Chinese influence in regional matters, which makes it an attractive counterpart for those concerned with the alleged Chinese quest for dominance.

None of this means that multilateral institutions have no role to play. While there are a range of these in Asia, none of them have moved beyond talk shops and require greater commitment and interest from ASEAN states and their partners alike. However, instead of trying to agree on the regional security architecture as a whole, the parties should focus on initiatives and treaties that could eliminate any chance of accidental interstate clashes. It is unlikely that Asian states will willfully engage in all-out warfare, but a maritime incident in the crowded waters of the Western Pacific may well escalate into something dramatic.

A build-up of trust measures like these may start a bottom-up process that could result in a denser network of albeit local and non-political, but efficient agreements. These can one day become something resembling a rules-based order Australia seeks.

First published in The Diplomat