25 Years of Coping: Key Economic Trends in Tajikistan

(votes: 2, rating: 5) |

(2 votes) |

Professor, Doctor of Economics, Head of the Economics Department at the CIS Institute, Leading Research Fellow at the RAS Institute of Economics

Tajikistan’s shaky economic development has been brought on by a number of factors: the Civil War caused significant damage to the country’s economy; the protracted period of recovery; the chronic deficit of financial and investment resources. All this has led to rather meagre advances in economic development, despite the relatively high economic growth, especially in the last decade. The situation is the result of the deindustrialization of the economy, the dominance of agricultural raw materials in the country’s exports, unresolved power shortage issues and dependence on remittances from Tajiks working abroad.

Along with the low level of basic development, the non-competitiveness of the economy and a lack of growth drivers, the cumulative effect of these risk factors has aggravated the existing economic situation in Tajikistan.

Investors are only ready to inject money into the Tajikistan economy against government guarantees, which leads to an increase in external debt made up of multilateral and bilateral loan agreements between creditors and the Tajikistan government.

With this economic model, the government of Tajikistan is trying, not unlike its Central Asian neighbours, to use investment to heat up its economy. However, faced with the lack of domestic resources, resorting to China as its main investor will not achieve this objective. China’s investment schemes are not designed to have a stimulating effect on the Tajikistan economy.

Tajikistan is one of the poorest agro-industrial countries in the world despite its considerable economic potential. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 63 per cent of the population lives on less than $2 a day (by purchasing power parity). A prolonged war and the associated disruptions and human losses sent the economy into a downward spiral (in 1995, its GDP was 41 per cent of its 1991 level). The Tajikistani economy is one of the weakest in Central Asia. The republic’s strong point is in its proven reserves of silver, lead, zinc and aluminium ores 1, its considerable hydropower potential and its competitive carpet weaving industry.

The Tajikistani economy is defined by its high dependence on imports, its underdeveloped agricultural sector, the almost complete absence of industrial production, a poorly qualified workforce (the majority of the working force is abandoning the country) and a production decline across the board. In 2012, agriculture accounted for 30.8 per cent of GDP, with the manufacturing sector contributing a further 29.1 per cent, and service industry contributing 40.1 per cent 2.

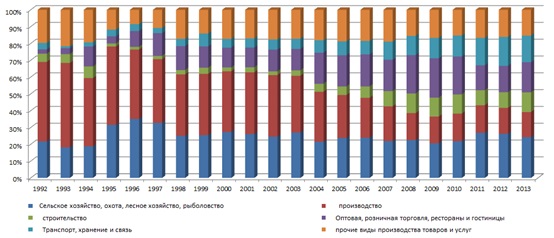

GDP Structure of Tajikistan by Sector

The dominant factor in the Tajikistani economy during the period from 1992 to 2015 was a trend towards deindustrialization. In 1992, industrial production accounted for 47 per cent of the republic’s GDP. By 2013, its share had shrunk to just 16 per cent. Agricultural output remained relatively stable during that period (growing from 20 per cent to 22 per cent). Meanwhile, the share of retail and wholesale trade increased from 3 per cent to 19 per cent, the construction sector grew from 5 per cent to 11 per cent of GDP, and transport and communications rose from 4 per cent to 16 per cent.

Fig. 1. Sector Composition of Tajikistan, 1992–2013

* Compiled by the author based on data from the UNCTAD Statistical Database and national statistical agencies. URL: http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx?IF_ActivePath

In contrast to other Central Asian republics, Tajikistan saw its share of other industries (the services and financial sectors) drop from 23 per cent to 7 per cent. This indicates a low level of development of small businesses and business activity prompted by a low demand for the services in question. The revised GDP sector composition for 2015 remains stable, showing a certain reduction in the agricultural output and in other sectors due to a drop in effective demand on both the domestic and external markets.

A distinctive feature of the sectoral composition of Tajikistan’s GDP is the roughly equal share of goods (46.4 per cent) and services (42 per cent) based on 2014 statistics. This ratio, however, demonstrates the republic’s low export potential given that the bulk of manufactured goods (with the exception of aluminium and raw cotton) are consumed domestically. The structure of industry in Tajikistan is primarily made up of the manufacturing industry (74 per cent, including aluminium production, petroleum processing, food and light industries), followed in a distant second by power generation and water production (19 per cent) and the mining industry (17 per cent). The main arable crops include raw cotton, grain and grain legumes, cucurbits and potatoes. In addition to considerable bureaucratic hurdles for doing business, a range of other factors have contributed to a slowdown in GDP growth.

In an economy dominated by privately owned and small-scale enterprises (65 per cent, with the share of publicly owned enterprises at 35 per cent) the government retains control over all infrastructure facilities and export-oriented operations (aluminium and cotton production). According to the World Bank, Tajikistan shows a very low level of entrepreneurial freedom. It scored just 44 points on the World Bank’s Index of Economic Freedom in 2015, placing it among those repressed countries that fail to facilitate the development of small and medium-sized enterprises. According to international estimates, regulatory practices in the republic are mostly of an authoritarian (repressive) nature. In a bid to overcome the severe bureaucratic limitations, the World Bank launched its Small and Medium Enterprise Development Project in 2009. However, the programme was not fully implemented because of a failure to comply with IMF requirements.

The following factors have contributed to the worsening of the sector composition and the slowdown of GDP growth in Tajikistan:

- The decline in demand for Tajikistan’s main export products – cotton and aluminium – has led to a drop in their production and a contraction of the manufacturing and agricultural industries, i.e. of the real sector;

- The decreased demand for the main export products has reduced the country’s foreign exchange earnings and, coupled with a decline in migrant worker remittances, considerably reduced domestic demand and imports (particularly, aluminium oxide imports used to produce aluminium);

- The 33.3 per cent decline in migrant worker remittances from 2014 to 2015 (the result of heavy reliance on workforce exports to Russia – the destination of 90 per cent of all migrants, and the sharp depreciation of the rouble) led to a significant drop in the value of the national currency – the somoni (with its official and market rates tumbling by 31.6 per cent and 38.6 per cent, respectively), as well as a 5.1 per cent surge in inflation according to official data; 1

- The low level of economic freedom and the lack of attractive investment industries has resulted in lower public revenue and higher foreign debt (which has increased from 22.7 per cent in 2014 to 27.9 per cent in 2015).

Along with the low level of basic development, the non-competitiveness of the economy and a lack of growth drivers, the cumulative effect of these risk factors has aggravated the existing economic situation in Tajikistan. A unique feature of Tajikistan’s economy is that it officially recognizes remittances from abroad as a growth driver for the economy and not just for the welfare of the population. This is due to the fact that, despite its best efforts, Tajikistan received the least external financing among Central Asian economies throughout the entire period that the study was conducted. The problem of low investment attractiveness has created a situation where the share of foreign direct investment has been reduced to an almost statistical error. In the recent years, Tajikistan has made considerable progress in resolving its foreign debt problem.

EU Towards Creating Its Own Eurasian Strategy

Investors are only ready to inject money into the Tajikistan economy against government guarantees, which leads to an increase in external debt made up of multilateral and bilateral loan agreements between creditors and the Tajikistan government. All told, Tajikistan’s foreign debt amounted to $2,194.5 million in 2015 (compared to $894.9 million in 2005), or 27.9 per cent of its GDP. This is without a doubt a considerable achievement, given that prior to 2000 external debt had consistently been above 100 per cent of GDP, peaking at 108.9 per cent in 2000. What is more, it is from this period that the foreign debt structure was improved considerably in regard to the composition of creditors. In 2007, Tajikistan’s major creditors were international financial organizations (responsible for over 74 per cent of the country’s total foreign debt) with 20 per cent more brought in by bilateral agreements (with Russia and Uzbekistan as its major creditor countries), and the remaining 6 per cent by other investments (including direct investments and investments against government guarantees) 4. The situation improved in 2015, with the pool of creditors expanding to include more countries. This also meant more that there could be more investments into specific development programmes rather than economic reform and crisis assistance programmes (the share of loans held by international institutions shrank to 40 per cent of the total loans, while creditors within the country accounted for 50 per cent).

The situation took a turn for the better in 2007 when China began investing heavily in the Tajikistani economy. Major Chinese investments began with $216.7 million in loans in 2007 and reached $888.7 million in investment in 2014. In 2015, the debt owed to China stood at 89 per cent of the total debt to creditor countries, with $1068.6 million payable to the Export–Import Bank of China and $12 million directly to the Chinese government (under a direct loan to the National Bank of Tajikistan). In total, the share of Chinese loans has reached 41 per cent of the total debt. Such a dependence on a single creditor appears to be a serious risk to Tajikistan’s financial independence. Chinese investment is crucial for Tajikistan’s infrastructure development.

The first Chinese loan (for $603.5 million) was signed in 2006 within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and was allocated to infrastructure projects to build transportation and power lines 5. Subsequent tranches were channelled into the completion of a railway line and highways, which are mainly used to transport Chinese goods to various locations. The transport routes were operating almost at full capacity as of the end of 2015.

The second loan (worth $6 billion) was also signed within the framework of the SCO in 2014. $3.2 Billion of the total loan was injected into the construction of a gas pipeline linking Turkmenistan and China, while the remainder was invested in transport lines and the development of mineral resources 6.

As of today, the effect of the new highways on the Tajikistani economy remains a moot point. The terms of the financing agreement implied that: 1) construction will be conducted by the Chinese side with the minimal involvement of Tajikistani resources; 2) management of the railway sections in question will be carried out by the Chinese investors under concession agreements; and 3) highway maintenance will be the responsibility of Chinese companies. The ambiguity of the economic effect of these investments stems from the fact that domestic transportation in Tajikistan, both in terms of domestic consumption and foreign trade, is insufficient to make the investment worthwhile, Heavier involvement of Chinese companies in the development of mineral deposits in Tajikistan only serves to further deepen the republic’s dependence on China. Therefore, in addition to the risks of payment defaults, Tajikistan appears to be completely at the mercy of China when it comes to strategic resource management and transit potential.

The situation surrounding the China–Afghanistan–Iran railway project is a glaring example. While Tajikistan has taken an active interest in the project (if the railway line passes through Tajikistan, it could help the country break away from its transport dependence on Uzbekistan), the country’s interests have been neglected for the sake of China’s 7.

Tajikistan’s Foreign Economic Activities

The U.S. in Central Asia: between «С5+1» and «Make America Great Again»

Tajikistan’s foreign economic activities are characterized by a chronic trade balance deficit, with import volume heavily outweighing exports. For instance, in 1993, imports grew by 171 per cent, while exports contracted by 37 per cent. In subsequent years, the imbalance in export and import growth rates evened out to a certain extent, but it remained larger than all the other Central Asian nations. In 2014, the gap shrank further, but the trade deficit still remained considerable at $235.6 million in 2014 and $168.7 million in 2015, or 9 per cent and 6 per cent and of GDP, respectively. In 2015, exports stood at $83.5 million (down from $91.3 million in 2014), while imports amounted to $252.2 million (compared to $326.9 million in 2014). The pattern of Tajikistani exports, however, has not shown any significant changes. It still includes finished products goods and products used as investment resources.

Continued import surpluses are the result of a wide range of commodities consumed domestically, while the export structure is limited to a small line of export goods produced in Tajikistan. The key export commodities in Tajikistan include aluminium, raw cotton, electricity, fruit and vegetables and mineral resources (gold, silver, zinc, lead, rare earth metals, etc.). In the export structure, the share of the main strategic export product (aluminium) declined from 73 per cent in 2008 to 23 per cent in 2014. This was the result of the inability of the Tajik side to negotiate investments on behalf of its main aluminium producer, TALCO, whose Russian investor pulled out of the project in 2007. Also, while the degree of asset depreciation calls for modernization, efforts financed by Chinese investment (which lacked the introduction of state-of-the-art technology) did not produce the desired results. Furthermore, the chronic electricity shortage has a detrimental effect on the volume and quality of the product. The increase in the shares of other commodities is linked to a rise in the country’s transit potential and the development of mineral resources, mainly by Chinese investors. The import structure has, in turn, been very consistent and includes a wide range of goods used as investment resources. For instance, aluminium oxide used in aluminium processing, petroleum products, non-ferrous metals, machinery and equipment as well as finished products such as wheat, flour, foodstuffs, electricity and natural gas are all included in the list of resources.

Tajikistan’s major export partners are the CIS countries (20 per cent) and all remaining countries (80 per cent). Of that total, 10 per cent is exported to Russia; 7.4 per cent is exported to Kazakhstan, 3.4 per cent is exported to the European Union; 10 per cent is exported to Iran; 40.7 per cent is exported to Turkey; and 7.4 per cent is exported to China. The main import partners of Tajikistan are the CIS countries, which provide 47.86 per cent of Tajikistan’s imports. This includes 15.1 per cent from Kazakhstan; 4.3 per cent from Kyrgyzstan; 21.96 per cent from Russia; 27.7 per cent from Turkmenistan; 2.3 per cent from Ukraine; 12.1 per cent from the European Union; 4.6 per cent from the United States; 4.28 per cent from Iran; and for 14.6 per cent from China.

Therefore, the structure of Tajikistan’s foreign trade confirms the economy’s competitive advantages and reflects economic growth driven by limited export resources and a heavy dependence on imports, particularly on those from other CIS countries. These competitive advantages are what are shaping the country’s production potential.

Economic, Financial and Foreign Exchange Risks

The economic model of Tajikistan is a system of economic relations with a quasi-market structure. The market is heavily regulated and competitive regulations and economic freedoms are almost entirely at the beck and call of the government. Meanwhile, this economic model also relies on domestic demand. Because direct foreign investment is limited (due to the country’s low investment rating) and production capacity is low, domestic demand is determined solely by the inflow of migrant worker remittances. In light of this, Tajikistan should be classified among those economies whose major export potential is formed on the basis of labour force migration, which is a major risk factor for the country’s economy. The level of risk increases dramatically amid uncertainty of foreign markets, specifically within the countries that host immigrants. In the case of Tajikistan, that host country is Russia, where the economic recession led to a considerable decline in migrant wages and a surge in inflation. The inflation spiral was prompted by the pressure on the Tajikistani somoni from the falling Russian rouble and a corresponding increase in the U.S. dollar rate. The national currency is susceptible to exchange rate fluctuations because of the high import share in the consumption structure. In 2014–2015, Tajikistan was under double pressure from the decline in migrant wages brought on by the falling rouble as well as a spike in prices due to the resurgent dollar. Tajikistan’s economy relies heavily on labour migration, which makes currency fluctuations a permanent risk for the economy.

The National Bank of Tajikistan was forced to resort to foreign exchange market interventions that nevertheless failed to have the desired effect. By the end of 2015, the somoni had plunged 46 per cent (from 4.77 to 6.98 somoni to the U.S. dollar, a drop of 2.21 somoni compared to the end of 2013). In that same period, the somoni had risen 69.85 per cent against the rouble (by 0.0435 somoni per rouble) 8. It was the combination of the falling rouble and the strengthening of the dollar that caused the inflation spike. According to official statistics of the National Bank of Tajikistan, inflation reached 5.3 per cent, while the World Bank puts the rate at 8.9 per cent. Therefore, consumer purchasing power is still shrinking at an accelerating pace, while product affordability is declining. To prevent a critical decline in consumption and possible social tensions, the government has elected to set upper price limits and install rigid compliance controls. The strategy, however, only postpones dealing with the deep-seated problems.

With this economic model, the government of Tajikistan is trying, not unlike its Central Asian neighbours, to use investment to heat up its economy. However, faced with the lack of domestic resources, resorting to China as its main investor will not achieve this objective. China’s investment schemes are not designed to have a stimulating effect on the Tajikistan economy.

Possible Scenarios for Economic Stability and Growth in Tajikistan

In this situation, there can be only two possible scenarios of further economic developments in Tajikistan:

- The “no-change” scenario: The ‘no-change’ scenario implies that the current policies will be maintained, restricting the inflation rate through price controls and anticipating an increase in investments and migrant remittances following economic recovery in Russia. This strategy may be justified in the short term, provided that sufficient resources are procured to support the social sphere (which is only possible with new loans from international creditors).

- The evolutionary scenario: This scenario involves a dramatic change in economic policies by expanding the investment base through large-scale industrial cooperation with CIS countries and with Iran. Cooperation could take place with CIS countries if Tajikistan could ascend into the Eurasian Economic Union. Cooperation with Iran in conjunction with Uzbekistan through the development of the country’s flagship industrial company TALCO is also possible. Furthermore, Russia, Kazakhstan and China are seen as likely interested parties with improved negotiating skills concerning cooperation. Russia, Kazakhstan and China could be utilized by helping to increase agricultural exports and by setting up agricultural processing facilities within the country. Therefore, this strategy involves the development of a new investment policy that would facilitate the creation of jobs and the development of the real sector. It would also require the deregulation of the economy (or at the very least, certain sectors thereof).

1. According to data provided by the Main Department of Geology under the Government of Tajikistan // Source: http://www.gst.tj/glavnaya/prirodnye-resursy

2. Aza A. Mihranyan. The economy of Tajikistan: 20 years of sovereignty // Source: http://www.materik.ru/rubric/detail.php?ID=14207

3. Based on official statistics of the Republic of Tajikistan; according to the Central Bank of Russia, the decrease in migrant remittances amounted to 51 per cent in 2015 compared to 2014, which is the result not only of the depreciation of the rouble, but also of new and more stringent rules on migrants from countries outside the Eurasian Economic Union.

4. As of January 1, 2016, Tajikistan owes money to the following international financial institutions: the World Bank (International Development Association) – $305.5 million; the International Monetary Fund – $130.2 million; the Asian Development Bank – $260.2 million; the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development – $110.77 million; the OPEC Fund for International Development – $40.23 million; and the EURASEC Anti-Crisis Fund – $70 million. Public Debt Report for 2015 of the Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Tajikistan. Source: http://minfin.tj/downloads/otchet_2015.pdf

5. The Chinese loans were used to build power transmission lines (South–North, Lolazor–Khatlon, Khujand–Ayni, the single power grid of the northern Tajikistan, reconstruction of the Regar electrical substation, construction of the Heating Power Plant Dushanbe-2), reconstruction and construction of new motorways (Dushanbe–Kulma Pass along the border with China, and Dushanbe-Chanak to Uzbekistan), the construction of the Vahdat–Yovon section of the Dushanbe–Kurgan-tube railway line, the construction of a cryolite and aluminium fluoride plant, and the modernization of Tajik Aluminium Company (TALCO).

6. In exchange for financing the construction of Heating Power Plant Dushanbe-2, Chinese companies were granted licenses to develop coal mines (Tajikistan is rich in coal reserves) according to the formula “investment in exchange for mining licenses.” In addition, a joint Tajikistan–China mining company began development of the Altyn-Topkan lead and zinc deposit near the town of Qayraqqum in Tajikistan’s Sughd Province; China’s Zijin Mining Group received a license to develop a gold deposit in Panjakent at the Tajikistan Gold Mining Plant, the buyout of which was completed in 2007.

7. According to the Tajik side, the 1972-km long Kashgar–Herat section (including the 392-km section running through Tajik territory) would grant Tajikistan direct access to the railway networks of Kyrgyzstan and China. However, with the total budget for the Tajik section estimated at $3.5 billion, China settled for a different route via Uzbekistan as a less expensive option. The project is being implemented on the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan route.

8. In 2016, the dollar continued to improve, rising by 56 per cent (2.8 somoni per U.S. dollar; from 5.03 to 7.86 somoni to the dollar compared to 2014). Based on data provided by the National Bank of Tajikistan. Source: http://www.nbt.tj/ru/kurs/kurs.php?date=30.12.2015

(votes: 2, rating: 5) |

(2 votes) |

Chinese Presence and Eurasian Integration

The U.S. in Central Asia: between «С5+1» and «Make America Great Again» EU Towards Creating Its Own Eurasian StrategyThe EU as a regional player in Central Asia

Greater Eurasia: Perceptions from Russia, the European Union, and ChinaCan Russia and the European Union cooperate within the new reality? What are the new mechanisms for EU-Russia cooperation? EAEU and SREB. Perceptions from China

Integrating Migrants in the Interests of Security and DevelopmentHow can we prevent the radicalisation of immigrants?

Proposals for Russia’s Migration Strategy through 2035RIAC and CSR Report