US - Cuba: a Wary Drift towards One Another

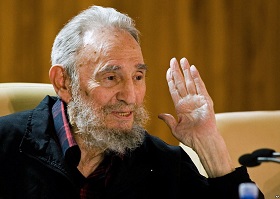

U.S President Barack Obama greets Cuban

President Raul Castro before delivering his

address at the Nelson Mandela Memorial in

Johannesburg, South Africa on

December 10th, 2013

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

PhD in Economics, Academic Secretary of RAS Institute for Latin American Studies

While the US-Cuban relations under Fidel Castro were never smooth or encouraging, decision-makers from both countries have shown credible interest in beginning possible cooperation or at the very least the process of normalisation. With the end of the Cold War, this kind of approach has slowly but surely begun to prevail.

While the US-Cuban relations under Fidel Castro were never smooth or encouraging, decision-makers from both countries have shown credible interest in beginning possible cooperation or at the very least the process of normalisation. With the end of the Cold War, this kind of approach has slowly but surely begun to prevail.

Cuban-American relations after the Cuban revolution

Relations between Cuba and the US began to worsen practically immediately during the aftermath of Fidel Castro taking power. Revolutionary changes in Cuba were launched in May 1959, with the expropriation of private land and the nationalisation of US-owned sugar refineries, telephone and utility companies. In September 1960, Cubans nationalised branches of North American banks in the country. Offers made by the US to settle the property issues were brushed aside by the revolutionary authorities. The Americans reciprocated by putting an end to offering oil supplies to Cuba and completely banning purchases of its sugar.

With economic ties between the two countries cut off, it was only a matter of time before their foreign policy relations deteriorated.

In April 1961, the US supported an attempted popular coup against Castro’s government, but Cubans failed to side with the rebels. Since then, there have been other attempts by Cuban migrant groups to land on the island.

In August 1990, Fidel Castro announced that Cuba was entering a "Special Period in Time of Peace”. Looking for ways to pre-empt a looming disaster, the Cuban leadership allowed some economic liberalisation.

The Cuban missile crisis, which followed the decision to station Soviet rockets with nuclear warheads targeted at US in Cuba, became a landmark event that scarred US-Cuban relations.

The reckless gamble attempted by Nikita Khrushchev and his cronies pushed the world to the brink of a nuclear war. Whoever would have been victorious in that war, be it the USSR or the US, Cuba would have suffered tremendously, but despite this fact, the Cuban leadership was even more bomb happy than the Soviets. Khrushchev and Kennedy stopped just short of a disaster.

In October 1962, because of its severe economic difficulties Cuba had to plead for assistance from Moscow, its key ally.

Soviet oil tankers left immediately heading for Cuba, in exchange for Cuban sugar which the Soviet Union had no need for and which was exported at higher than the then prevailing world prices.

Meanwhile, the US Navy set up a blockade of some 500 nautical miles around the island. In February 1963, the US passed the Cuban Assets Control Regulations Act introducing restrictions that were to become the principal leverage in the US’s Cuban policy. Since 1966, US citizens have been banned from visiting Cuba.

Disintegration of the USSR and the socialist camp. Transformations in Cuba and their effect on relations with the US

Between 1960 and 1987, close political, economic and military ties between the USSR and Cuba were based on ideology and came in the form of paternalist assistance by the Soviet Union. Cuba received a range of goods, from food and children’s clothes to machines and technological equipment. With the disintegration of the USSR, this assistance stopped, resulting in a 34.7 per cent drop in Cuba’s GDP, while the government budget deficit soared to 33 per cent of GDP [1].

In August 1990, Fidel Castro announced that Cuba was entering a "Special Period in Time of Peace”. Looking for ways to pre-empt a looming disaster, the Cuban leadership allowed some economic liberalisation: more private enterprise and less restrictive foreign exchange [2].

There were also some attempts at increasing foreign investment. The legal framework for the new course to be adopted by the Cuban government vis-à-vis foreign investors was established by Decree Law No 50 passed in February 1982. This document allowed for the national treatment of foreign investors with regards to taxes, banking and labour laws [3]. In the country itself, authorities introduced strict rationing of electricity, food and consumer goods.

As for US-Cuban relations, the first triggers was set off by events happening elsewhere in the world. US legislators and public figures started to pay visits to Cuba. In early 2002, Fidel Castro received a large group of US legislators and businessmen, who afterwards voiced their willingness to lobby for the lifting of the US embargo. All that resulted was a tangible warming, if not a normalisation, of relations between the two countries. The Cuban Government condemned the 9-11 terrorist acts in New York and Washington, and three years later, on 20 December 2004, the National Assembly of the People’s Government approved Cuba’s accession to all international treaties combating terrorism.

In May 2002, Cuba was visited by US President Jimmy Carter who advanced a four-item plan for normalizing relations between Cuba and the US:

- lifting restrictions on travel to Cuba;

- lifting the embargo;

- settling property disputes arising from the US property nationalisation following the 1959 revolution;

- relying on the Cuban diaspora in the US to act as a bridge between the two countries [4].

US-Cuban Relations Today

Any prospects for a major change in the US-Cuban relationship will depend to a large extent on the political and economic situation in Venezuela, which has been effectively the sole pillar in the fragile Cuban economy. Venezuela supplies Cuba with almost US$ 5 billion worth of oil and petroleum products.

Since 2010 Cuba has tried to alleviate its “oil dependence” and explore the Mexican shelf with the help of Russia’s Gazpromneft. However, oil in that part of the shelf has proven too difficult to recover and, in September 2013, Gazpromneft pulled out of the project after having invested at least US$ 12 million [5].

The Venezuelan Government led by Nicolas Maduro relies heavily on populist measures such as limiting the prices of goods and the rate of return for businesses or restricting foreign trade, which, while it possibly leading to a short-lived swell in the popularity of government among the poorest, negatively affects its domestic economy. Because Nicolas Maduro won the election with just under a one per cent vote margin, and because he lacks charisma of the late Hugo Chavez, Venezuela is very likely to see major developments sometime soon, with a concurrent risk of the suspension or, at the very least, a major reduction in Venezuelan assistance to Cuba. This will be a disaster for Cuba, on the scale of severing ties with the USSR. And since Cuba will not be able to find another donor like Venezuela, this is bound to push the country back to the process of normalizing relations with the US.

Venezuela is very likely to see major developments sometime soon, with a concurrent risk of the suspension or, at the very least, a major reduction in Venezuelan assistance to Cuba. This will be a disaster for Cuba, on the scale of severing ties with the USSR.

Many observers believe the US embargo to be the key negative factor in the US-Cuban relationship. But while the embargo is a nuisance, the problems of the Cuban economy lie with the paternalist government which has removed any incentives to work as well as sanctions for laziness. As a result, Cubans are not exactly overworking at their official jobs [6]. Moreover, despite the embargo, there is a boom in trade, in particular in goods imported from the US. In 2012, trade between Cuba and the US amounted to US$ 464.5 mln, and in just four months of 2013 alone it reached US$ 177.1 mln.

In my opinion, those who follow the US-Cuban relationship make too much of what US presidents think. The situation cannot be explained only by the personal likes or dislikes of this, that or the other US president.

According to Henry Kissinger, Americans have commitments to certain principles unrelated to any specific interests evident on the surface [7]. One of these such commitments is to human rights and freedoms, but only where they see it fit.

During the presidency of George W. Bush, the embargo notwithstanding, the farmers’ lobby in the US Congress clinched permissions to supply agricultural goods to Cuba. And although the terms were draconian, requiring a 100 per cent advance settlement and no recourse to US bank loans, the US became the chief source of food for the Cubans (worth over US$ 500 mln a year), which has helped to alleviate food hardships in Cuba.

President Barack Obama has referred to a “new approach” to Cuba many times. One such occasion was in November 2013 in Florida, when he said that the US may revise its sanctions against Cuba: “Keep in mind that when Castro came to power I had just been born, so the notion that the same policies that we are putting in place in 1961 will somehow still be as effective as they are today in the age of the Internet, Google and world travel doesn't make sense." In addition, according to Barack Obama, the younger generation in the U.S. is more open to finding "new mechanisms" for resolving bilateral issues.

In the light of the recent scandal with the former US intelligence agent, Edward Snowden, who planned originally to leave Hong Kong for Havana according to some Western mass media he had to abort his plans because of the Cuban stance. Presumably, Cuba’s position in that issue was its unwillingness to jeopardise its relations with the US.

The future of US-Cuban relations

The future of US-Cuban relations hinges on the island’s economic situation. There are several possible scenarios. For geopolitical reasons, Cuba may be taken in tow again by Russia or by some other country, like Iran, for instance, in exchange for cooperation in the military sphere (training of army officers or deployment of military bases). With either option being purely hypothetical, there will be hard times for Cuba’s economy in the foreseeable future. The country will then need some radical measures again to avoid an economic collapse, which, in turn, may require further liberalisation in political life. However, as far as radical change goes, we can hardly expect that as long as powerful and numerous security officers in Cuba are satisfied with their level of welfare, they will not allow any spontaneous political developments. After half a century of one-party rule and after the unprecedented exodus of over one million Cubans from the island (almost 10 per cent of population), guarded steps towards political change can only be initiated from the top.

Undoubtedly, any progress in the sphere of human rights and the lessening of tension in intergovernmental relations will help normalise the US-Cuban relationship.

Slow but clear shifts in the areas of civil rights and liberties in Cuba are happening gradually. Many dissidents have been released in recent years, and people have been allowed to travel abroad. In turn, the US has started to issue multiple visas to Cuban citizens. In June 2013, Washington held unmediated talks to restore postal links with Cuba. Cuban authorities announced they were allowing wider internet access in public places. The country now has numerous cyber cafes, and there are no restrictions on mobile communications. Even the very sensitive issue of sexual minorities is being addressed gradually in Cuba.

In their relations with the US, Cuban authorities have somewhat watered down the anti-imperialist tone of visual and other propaganda.

Undoubtedly, any progress in the sphere of human rights and the lessening of tension in intergovernmental relations will help normalise the US-Cuban relationship. On the other hand, the US embargo, key to that issue of normalisation, can only be lifted if American owners are compensated for the property expropriated by Cuba. While Cubans may not have the wherewithal to compensate them, they also have no desire to do it either. Americans, however, may be prepared to accept some tradeoff, a restructuring or even a partial write-off. What is important to the US is the principle: a recognition of illegal expropriation, which may be open to concessions by both parties.

While the current Cuban leader, Raul Castro, is no proponent of a market economy or a support of human rights, some of his steps, including limiting the term in office for the leading posts (he has limited his own to 2018) may ease the way towards a post-authoritarian society. Economic reforms alone in Cuba are arguably insufficient to make a breakthrough and the leap into becoming a market economy as China or Vietnam have done.

In November 2013, the US officially abandoned the 190-year old Monroe Doctrine, which warned European powers against attempting to colonise the Western Hemisphere, while the US, in return, pledged not to interfere in the domestic affairs of European countries.

Speaking at the Organization of American States in Washington, D.C., on the occasion of the renunciation of the Monroe Doctrine, State Secretary that the US looked “…forward to the day – and we hope it will come soon – when the Cuban Government embraces a broader political reform agenda that will enable its people to freely determine their own future.”

1. Russia and Cuba in the context of economic globalisation. Moscow: ILA RAN, 2005, P. 496 (in Russian)

2. Modern Cuba. Challenges of economic adjustment and re-focusing of foreign ties. Moscow, 2003, P. 158 (in Russian)

3. New opportunities for investing in Cuba. A Businessman’s Handbook, compiled by E. Beliy. Moscow, 1997 (in Russian)

4. Juventud rebelde, Habana. 19.05.2002

5. The Kommersant, 16.09.2013 (in Russian)

6. The Economist, 24 March 2012, London.

7. H. Kissinger. Diplomacy, 1997, Moscow: Lidomir, P. 384 (in Russian)

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |