Fragmentation of the digital space into competing models of managing cross-border data flows is a challenge to the digital domain and its prospects. ECOSOC is a good example of how international institutions can interact with NGOs. However, it will not do to simply copy its mechanism, and it is so for several reasons. First, final recommendations within ECOSOC are adopted by representatives of member states. This harms its usefulness as a model to be replicated, since there will always be the risk that issues are politicized. Second, the ad hoc mechanism to engage NGOs, which works perfectly fine for ECOSOC, may not be enough when it comes to technical standards that need to be constantly updated. Third, the General Assembly elects ECOSOC members every three years. However, this would not be feasible for the new coordinating body as the digital domain has its own leaders, and leaving them overboard would be incredibly detrimental to its effectiveness.

Moreover, the choice of decision-making mechanism presents certain difficulties given the dominant position of the four, both on the international stage and in terms of data processing. Operating on the basis of consensus may hinder negotiations or become an instrument to block unwanted decisions, while a simple majority will likely result in these nations establishing ad hoc coalitions to try and swing votes in their favour. Therefore, it seems prudent to design a complex voting mechanism based on qualified majority, possibly drawing on the system used in the Council of the European Union. Still, this mechanism will not rule out struggles unfolding behind the scenes.

Finally, the fact that the two sides have fundamental disagreements as to the concept of sovereignty in the digital space should be accounted for, as this could put an end to the new coordinating institution before it has even been established. The only way to move forward with a truly effective platform for cooperation in the digital space is to temporarily improve, if not to normalize, the relations between the leading states in this area.

Multilateral agreements that do not address the fundamental differences in the stances taken by states may lay the foundation for global governance to emerge in the future. It is in this context that the joint U.S.–Russia draft resolution on the responsible behaviour of states in cyberspace, if legally unbinding, bears utter significance for cooperation between nations who espouse two different models as well as for overcoming the negative background of broader political disagreements.

Today, information space has become a field of confrontation involving major digital platforms, governments, societies and individual users. Stories featuring latest cyberattacks or state-sponsored attempts to limit the influence of social networks and regulate the digital sphere, where there is no governance at the international level, are those that grab the headlines of many online media outlets.

Given the current climate, it is then no surprise that the United Nations is paying close attention to the issues related to the digital domain. On September 29, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development released its Digital Economy Report 2021, which focuses on the issue of managing cross-border data flows. The piece is rather comprehensive in terms of the issues covered, seeking to analyze the inhibiting factors that prevent us from working out an exhaustive definition of what “data” is, while exploring the specific approaches of states to regulating cross-border data flows. The report’s authors pay particular attention to the digital divide that has emerged between developed and developing nations. That said, we would argue that the report is more of a descriptive paper rather than a real step towards erecting a system of global governance.

The first section of the report addresses the lack of clarity on the definition of “data”, whether in research or among practitioners. With no unified terminology, communication between stakeholders appears to be complicated, much as the process of designing public policy as regards the digital sphere. A generally accepted and unified terminology would no doubt make it easier to foster closer cooperation, although this is certainly not a defining prerequisite. International efforts to fight against terrorism can be a case in point here, as there is no conventional definition of “terrorism,” while this does not hinder inter-state cooperation, both regionally and globally. While this cooperation may not always proceed smoothly, any problems encountered tend to be the upshot of political squabbles rather than the implications of the fact that no single definition of “terrorism” is to be found.

The UNCTAD report brings up another underlying premise, which is that data should be treated as a global public good. This will allow citizens, acting as “producers” of raw data, to claim the benefits of it being used by digital platforms. This issue has already been discussed at the EU, with the approach tested in a number of cities. Transferring some control over the flow of data from corporations to users is an important step towards ensuring that human rights are upheld in the digital environment.

The UNCTAD report also explores the technological and digital divide, whose dimensions span developed and developing countries as well as urban and rural areas within a particular country. This problem is nothing new: it was only last year when UN Secretary-General António Guterres referred to the need to bridge the gap, arguing that it was instead widening amid the COVID-19 pandemic. At the same time, he proposed a Roadmap for Digital Cooperation.

Besides, the report notes the massive impact of digital platforms. These, the authors believe, “are no longer just digital platforms” but “global digital corporations” that have the necessary capabilities for processing information, which puts them in a privileged position. Further, digital platforms are able to influence policymaking through lobbying their interests. In terms of spending, Facebook and Amazon are the most active lobbyists in the United States, while Google, Facebook and Microsoft are the biggest spenders in Europe. The report suggests that the privileged position of digital corporations—such as their ability to process massive bulks of data and derive profit from raw information—leads to something of an imbalance between the private and the public sectors when it comes to recruiting talent. Accordingly, the gap is widening, which means that the tech giants are moving even further out in front.

Finally, fragmentation of the digital space into competing models of managing cross-border data flows is another challenge to the digital domain and its prospects. Should such fragmentation occur, this may create new obstacles to communication and economic development, as the existing models (those of the U.S., the EU, Russia, China and India) offer different regulatory practices that have their own flaws and inefficiencies. The report identifies the broad shortcomings of these practices, making note of poor coordination between government agencies; ambiguous formulations deliberately used to denote key concepts (such as “critical infrastructure” or “digital sovereignty”); and setting unrealistically high technical requirements, including the requirement to store personal data locally—something that entails greater costs for smaller businesses and is detrimental to end consumers of digital products and services.

The Digital Economy Report implies the solution lies in establishing a new institutional framework to meet the challenge of global governance in the digital domain. This new institution should contain the “appropriate mix of multilateral, multi-stakeholder and multidisciplinary engagement.” At the same time, the report argues for ad hoc interaction between stakeholders given the inherent complexity of the framework. The new organization should become a coordinating body for digital governance with a sound mandate.

Indeed, the main stumbling block for global governance to emerge in the digital sphere has to do with the model of interaction to be chosen. The epitome of the intergovernmental approach is the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), while the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) is illustrative of the multi-stakeholder approach.

Since neither is perfect, this naturally leads us to the conclusion that a combined approach is what is needed. This approach can possibly provide states with a much-needed platform for broader involvement in issues of digital governance, while ensuring that non-state actors and expert community retain their positions. The UNCTAD report refers to the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) as a perfect example of such a “hybrid” international organization. At ECOSOC, interaction with NGOs takes place through the Conference of Non-Governmental Organizations in Consultative Relationship with the United Nations. Expert bodies made up of representatives of individual countries as well as of independent experts also operate within the framework of ECOSOC.

Indeed, ECOSOC is a good example of how international institutions can interact with NGOs. However, it will not do to simply copy its mechanism, and it is so for several reasons. First, final recommendations within ECOSOC are adopted by representatives of member states. This harms its usefulness as a model to be replicated, since there will always be the risk that issues are politicized—this will be the case even if the new institution is designed with the combined approach in mind. Besides, should this body take on the role of the principal coordinator in the digital space, issues will become more politicized and disagreements will be more heated, thus slowing down decision-making. Second, the question remains as to how the new institution will interact with the existing organizations, namely the Internet Architecture Board and the Internet Engineering Task Force. The ad hoc mechanism to engage NGOs in other areas, which works perfectly fine for ECOSOC, may not be enough when it comes to technical standards that need to be constantly updated. Third, the General Assembly elects ECOSOC members every three years. However, this would not be feasible for the new coordinating body as the digital domain has its own leaders, and leaving them overboard would be incredibly detrimental to its effectiveness. In such a case, there remains the above-mentioned risk of discussions between the U.S./EU and Russia/China becoming politicized.

Moreover, the choice of decision-making mechanism presents certain difficulties given the dominant position of the four, both on the international stage and in terms of data processing. Operating on the basis of consensus may hinder negotiations or become an instrument to block unwanted decisions, while a simple majority will likely result in these nations establishing ad hoc coalitions to try and swing votes in their favour. Therefore, it seems prudent to design a complex voting mechanism based on qualified majority, possibly drawing on the system used in the Council of the European Union. Still, this mechanism will not rule out struggles unfolding behind the scenes.

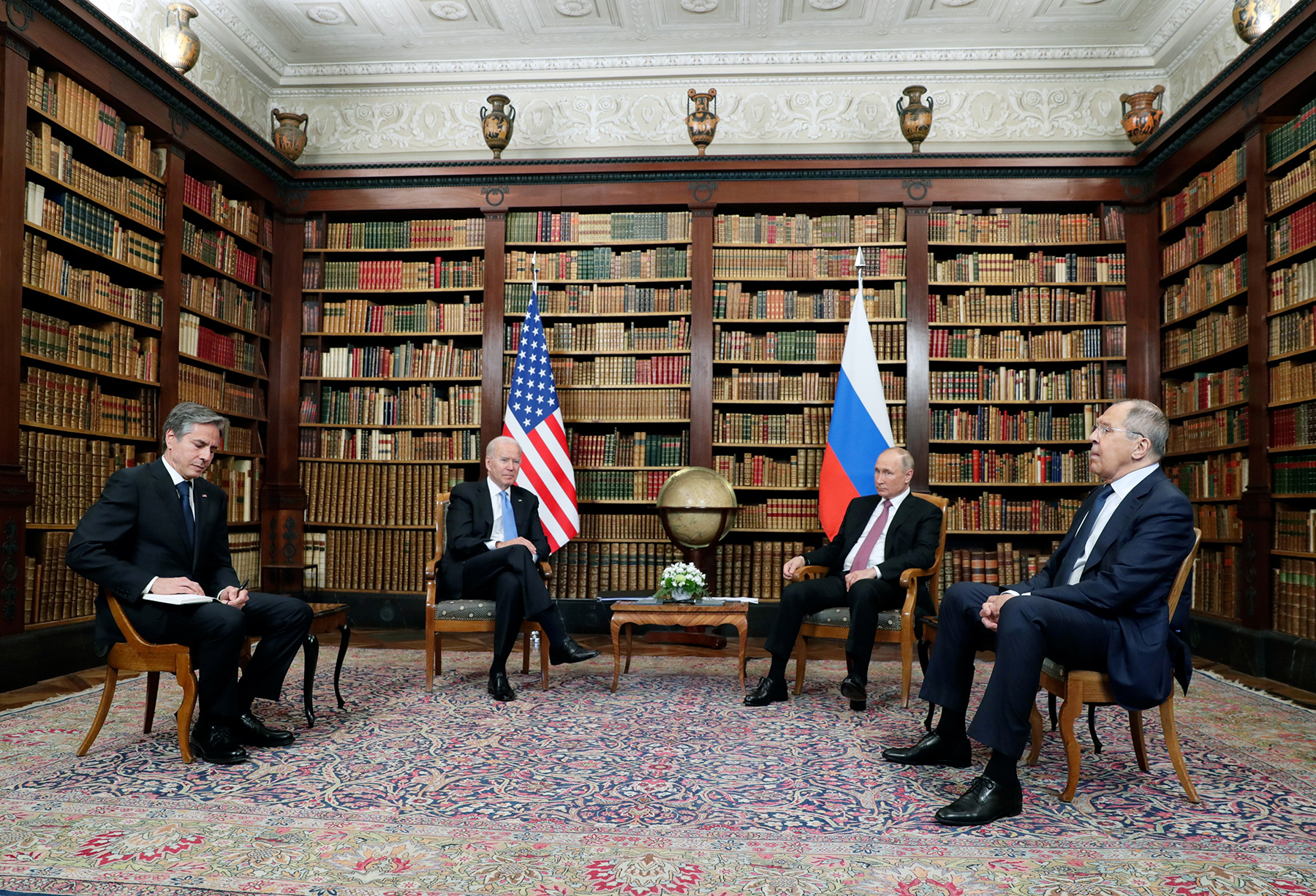

Finally, the fact that the two sides have fundamental disagreements as to the concept of sovereignty in the digital space should be accounted for, as this could put an end to the new coordinating institution before it has even been established. The only way to move forward with a truly effective platform for cooperation in the digital space is to temporarily improve, if not to normalize, the relations between the leading states in this area.

No global governance in the digital domain is better than a poorly regulated system spinning its wheels. Our modern world is too dependent on technological advances that ensure that all regions and facets of life are complementary. Any failure of the mechanism can be extremely costly. However, increasing fragmentation of the digital space may be even more costly—for developing and developed countries alike. One possible way forward amid the international environment mired in uncertainty is to search for common ground on the most basic of issues. While the differences in national regulations persist, there are a number of issues that are common to all: these include cyberterrorism, cybercrime, illegal access to data or threats to critical infrastructure.

Multilateral agreements that do not address the fundamental differences in the stances taken by states may lay the foundation for global governance to emerge in the future. It is in this context that the joint U.S.–Russia draft resolution on the responsible behaviour of states in cyberspace, if legally unbinding, bears utter significance for cooperation between nations who espouse two different models as well as for overcoming the negative background of broader political disagreements.