The Scale of Labor Migration to Russia

(votes: 2, rating: 5) |

(2 votes) |

PhD in Geography, senior researcher, Institute of Demography HSE

The main outcome of the last decade in the field of labor migration can be seen in the concord eventually reached between the expert community and decision-makers on labor migration's necessity for the development of Russian economy. The next step is the resolution of other, more sophisticated issues. First among them is assessment of the number and skills of labor migrants needed in Russia.

Late in the 20th and early in the 21st century, the inflow of labor migration became visibly dominant among other migration flows, and its scale has substantially increased over the last decade [1] (See Figure 1).

The number of labor migrants officially employed in Russia (as shown in the chart) is far from the total of all foreign workers present within the Russian labor market. According to expert estimates, the number of foreign migrants without an employment permit, i.e. those working illegally, is at least two or three times greater than the official statistics. In general, the data spread in the estimates of foreign migrants’ presence in Russia has always been very wide: “according to different estimates, the number of illegal labor migrants in Russia varies from 1.5 to 15 million people” [2]. However, the majority of experts believe that the figures of 12, 15 and even 20 million migrants quoted from time to time are clearly an oversized estimate. While earlier in the decade the number in question was approximately 3 million labor migrants [3], by the end of the decade the coordinated expert estimate of the annual number of labor migrants in Russia (both legal and illegal) was 4-5 million people [4]. On the whole, experts believe that over the last decade the dynamic of the general inflow of labor migrants to Russia “though growing in its volume, does not feature a rapid upsurge” as an official component [5].

Figure 1. Number of foreign nationals engaged in labor activity in Russia, (thousands)

Source: Russian Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat) data.

The representatives of the Federal Migration Service (FMS) also share the expert assessment of the overall number of labor migrants at present. The head of the FMS quoted the figure of 9.5 million foreign nationals staying in Russia. “Approximately 1.3 million are legally employed; 3.7 million stay “as guests”, so to speak… About 3.2 million migrants from the risk category of 4.5 million stay in Russia for more than 3 months, and are likely to work illegally in order to subsist, consequently evading taxes,” he said. “Therefore, about 4.5 million foreign nationals stay in Russia and are legally or illegally engaged in labor activity,” he concluded [6].

The correlation between the legal and illegal components of labor migration to Russia changed substantially over the decade in question. Essentially, the correlation was influenced by the changes in migration laws and law enforcement practices in the field. The most illustrative example is the liberalized migration legislation of July 18, 2006, when the following legal acts were adopted: the new Federal Law “On Migration Registration of Foreign Citizens and Stateless Persons in the Russian Federation” (# 109-FZ) and the law “On Legal Status of Foreign Nationals” (# 110-FZ). Both came into force on January 15, 2007. Among the main new features for the migrants were the following: migration registration at the place of residence became a notification procedure instead of a permit acquisition, and the work permit would now be issued to the migrant personally, instead of their employer as was the case earlier (i.e. it cancelled the strict attachment of a worker to their employer). The above chart clearly indicates that over the two years, upon adoption of the new laws (2007 and 2008) the regulated component of labor migration increased 2.5 times! For the first time, Russian legislation attempted to fight illegal forms of labor migration “not by way of strict limitations, but on the contrary, by way of granting a wider freedom of movement to migrants through simplification of registration and employment procedures, and the creation of an unhampered environment for legal formalization” [7].

In a way, the drop in the number of migrants working in Russia registered since 2009 (Figure 1) was an aftereffect of the world economic crisis [8], which seriously impaired the situation in the Russian labor market and, to an extent, took away the jobs not only of labor migrants but also of Russian citizens (according to expert assessments, the overall volume of labor migration to Russia went down by 10%). However, official statistics of labor migration displayed a much larger fall: for instance, in 2009 the number of work permits issued in Moscow fell by nearly 40% as compared to 2008. Thus, under the pretense of protecting the national labor market during the crisis, the authorities artificially reduced the number of migrants working in Russia, which hardly reflected the actual state of affairs. Toughening law enforcement practices [9], introduction of restrictive changes and amendments into the new migration legislation, as well as a disproportionately abrupt reduction of quotas on work permits issued to labor migrants, once again reduced the legal component of the inflow and drove a substantial proportion of foreign workers seeking legalization back into the “shadow market”.

In 2010 and 2011, despite the end of the crisis, the number of officially employed labor migrants continued to go down (the 5% growth in 2011 can be hardly seen as a change in the trend). This was a direct result of restrictive policies pursued in this field, including continued reduction of quotas on work permits issued to foreign nationals: in 2007, at the time of the new migration laws coming into effect, the quota was highly liberal and granted 6 million permits; in 2009 it was 3.977 million permits; in 2010 it was 1,944, and 1,746 in 2011. At the same time, the overall presence of labor migrants in the Russian labor market was reportedly restored to the pre-crisis level (4-5 million).

The toughening of the procedures for acquiring a work permit by labor migrants was partially alleviated by two other channels to legalize the foreign work force: the introduction of special preferences for foreign highly skilled workers, and of a patent for migrants employed by private individuals (both categories being allowed to work in Russia without quota limitations). The above categories of labor migrants appeared in Russia on July 1, 2010, under the amendments introduced into the Federal Law # 155-FZ “On Legal Status of Foreign Nationals in the Russian Federation”. Regrettably, the number of highly skilled specialists employed under the procedure is still small (about 14.4 thousand people over 2010 and 2011), which is caused by highly strict requirements to their salary – not less than two million RUR per annum. At the same time, the number of migrants working under a patent is growing considerably faster (the price of a patent is 1000 RUR a month, and is fully affordable to many labor migrants): in 2010 (from July through December) 157,000 patents were issued, while in 2011 there were already 866,000. Hence by the beginning of 2012, more than one million foreign nationals were granted a legitimate right to be employed by private entities [10].

The Main Supplier Countries of Labor Migrants to Russia

By the year 2010 the share of the “far abroad” in the aggregate number of foreign nationals legally working in Russia went down to 24%. Thus, three quarters of official foreign workers in Russia are citizens of CIS member countries.

Migrants are coming to work in Russia from dozens of countries. Over the decade in question (2000-2010) the proportion of key suppliers of the work force to Russia has varied considerably.

Above all, over the recent years the correlation of the contribution of countries of the “far abroad” and CIS members has cardinally changed: according to official statistics, within 2000-2005 their share in the inflow of labor migrants was approximately identical (the CIS countries were only fractionally behind the “far abroad”), and in 2006 labor migration from the CIS slightly exceeded the level of migration from the “far abroad”, while since 2007 the number of labor migrants from the CIS considerably surpassed the inflow of labor from abroad. The key reason for these cardinal changes was the introduction of new migration laws in 2007 (see above) granting large privileges to CIS laborers. They were allowed to obtain work permits independently, without an employer, while the employers of workers with an entry visa requirement still have to apply for a permit of engagement and work.

In 2006, 47% of one million work permits were issued to “far abroad” nationals, and 53% to CIS citizens, while next year the ratio was 67% to 33% in favor of CIS migrants out of 1.7 million permits. By the year 2010 the share of the “far abroad” in the aggregate number of foreign nationals legally working in Russia went down to 24%. Thus, three quarters of official foreign workers in Russia are citizens of CIS member countries.

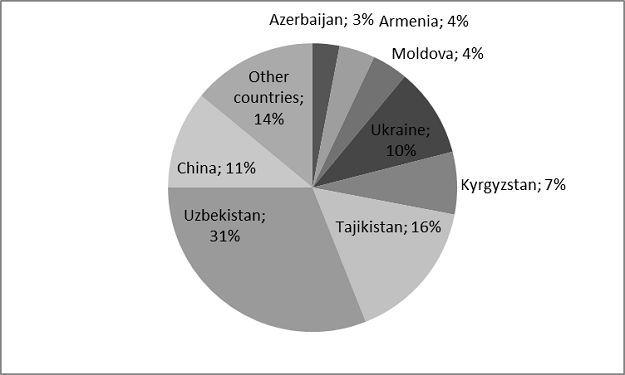

The shares of the countries of origin have also changed substantially over the decade. In 2000 the champion in the number of legally working migrants was Ukraine (30% of the inflow), the second was China (13%), then Turkey (9%), Vietnam (7%) and Moldova (6%). By 2006 the leaders were Ukraine and China (though the Chinese share was somewhat larger than the Ukrainian contribution – 21% against 17%), the third was Uzbekistan (10.4%), then Turkey (10%) and Tajikistan (9.7%). Since 2007 the uncontested leader has been Uzbekistan (20% in 2007, 26% in 2008, 30% in 2009), and the second largest donor is Tajikistan (15%, 16.1% and 16.2%, respectively). They are followed by China (11–12%) and Ukraine (about 10%). Since 2008 the fifth donor country is Kyrgyzstan (about 7%).

In general, the largest tangible changes were registered in the shares of three Central Asian countries. If in 2005 three Central Asian countries (Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan) represented 16.8% of the total migration influx into Russia and 34.4% of the CIS inflow, already in 2008 citizens of the above states comprised more than 50% of the aggregate legal foreign labor force in Russia, and 68.5% of CIS workers [11]. By the year 2010 those three countries presented about 55% of all foreigners officially working in Russia and nearly three quarters (73%) of CIS nationals (Figure 2). The majority of experts believe that by and large the figures correspond to the statistics on legally working foreigners, with minor exceptions. In particular, the expert assessment of Ukraine’s share in the aggregate volume of labor migration is noticeably higher than official statistics and is close to 15-16% [12] (close to Tajik figures). To be precise, the number of illegal laborers is especially large among the Ukrainian labor community as they are much less troubled by police checks; the prolongation of migration registration based on official labor contracts is a far less important issue because they can briefly leave Russia every three months and then return to work.

Portrait of a Labor Migrant

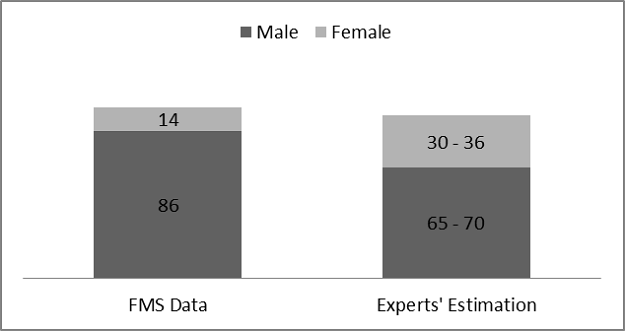

Over the last decade the image of a labor migrant coming to Russia has changed dramatically., The labor migrant is typically male. The share of females among legally working migrants increased from 10% in 2000 to 15% in 2055, and over the recent years has stood at the level of 14-15%. However, experts believe that the share of females is substantially larger and has reached the level of 30-35% over the recent years (Figure 3). Official statistics underestimate the number of females because of special features of their employment – females are more often employed in the informal sector, by private employers, etc., without officially formalizing their employment.

Another change involves age distribution within the labor inflow – the number of younger people (less than 29 years old) has grown: the share of this age category increased from a quarter in 2000 up to nearly 40% in 2010.

Modern labor migrants predominantly belong to the titular ethnic groups of their countries of origin. Respectively, the prevailing ethnicities are from Central Asia (more than 50%); Ukrainians and Moldavians make approximately a quarter of the flow, and trans-Caucasians about 13%. Russians make up less than 10% of the influx [13].

Foreign laborers have become less educated – about 40% of their number have no vocational training. Inhabitants of small towns and villages are more often going to Russia (from one half to three quarters of the inflow). Migrants are getting poorer (according to recent polls, more than 40% claimed that they “have money for the bare necessities of life only”, or even “have no money to survive”).

The labor migrant is typically male. The share of females among legally working migrants increased from 10% in 2000 to 15% in 2055, and over the recent years has stood at the level of 14-15%.

More often labor migrants are coming with their families: about one third take along their spouse (among female migrants the share of those accompanying their husbands is more than 50%), and about 10-15% take their children (the majority of laborers coming with children - 80% - are two-parent families).

The command of the Russian language among the migrants has also changed, though the situation is not at all disastrous. About 20% have no or only elementary command of Russian, and communicate mostly in their native language; they find difficulties in communicating while at work. About one third of the migrants feel lacking in Russian language when visiting shops or drugstores, and about one half have troubles when formalizing their documents.

More often labor migration becomes a long-term project – according to Rosstat, in 2010 only 22.5% of migrants worked in Russia for less than six months, another 17% from 6 to 9 months, and more than 60% worked for the period of 9 to 12 months (i.e. stayed in Russia for nearly a year). Practically the same results were reported by the polls undertaken by the Center for Migration Research [14]: more than 60% of respondents pursue a long-term migration strategy, 40% of their number admitted that they mostly stay in Russia going on leave for one to three months only, and 25% declared that they practically reside in Russia and never go home. In fact, the last category of migrants comprises the people permanently residing in Russia and concentrating on seeking Russian citizenship. The percentage of such migrants has remained unchanged over the years – about one quarter of all labor migrants coming to Russia.

Demands of the Russian Labor Market

Since 2006, Russia has begun to feel short of able-bodied population. While in 2006 the able-bodied population loss was insignificant and totalled 176 thousand people, in 2009 it exceeded 900 thousand people or 1% of the entire working population (on January 1, 2010 it reached 88,360 thousand people). In the future, the loss of able-bodied population will grow. Following the average predicted scenario of Rosstat, between 2011 to 2025 it shall exceed 10 million people. According to many experts [15], it would be impossible to offset such an enormous loss of active population (more than 12%) within a short time period through higher labor efficiency, restructuring of economy, or by attracting a part of the economically inactive native population (housewives, pensioners, disabled people etc.) into the labor market. More active leveraging of the potential of internal labor migration would not resolve the problem either, as the shortage of labor would gradually hit all Russian regions. Thus, within the next 10-15 years Russia will be unable to do without employment of foreign labor, and at ever greater levels.

Anatoly Vishnevsky:

The New Role of Migration in Russia’s

Demographic Development

However, today it seems impossible to predict the demands of the Russian labor market in specific numbers of Russian and foreign workers. There are at least two reasons. First, official statistics on vacancies, as collected by the national employment agencies, are highly inaccurate because a vast number of enterprises and organizations fail to present data on newly vacant positions to the employment authorities (though they are required to do so), and seek new employees on their own [16]. Second, the scale of employment in the informal sector is enormous. According to Rosstat, one fifth of employed Russians are working in the informal sector [17]. According to experts, the informal sector is extremely difficult in terms of quantitative assessment [18] (consequently, the labor demands of the sector are practically unknown).

Nonetheless, available (even if incomplete) statistics of the Ministry of Public Health and Social Development, based on the employers’ labor needs as presented to the employment services, offer a clear picture of the general tendency. The shortage of workers over crisis and pre-crisis years was changing as follows: from 1,124 thousand in 2007, 895 thousand in 2008 and 725 thousand in 2009 up to 982 thousand workers in 2010. By the end of 2011 it reached nearly 1.200 thousand, i.e. returned to the pre-crisis level and even surpassed it. According to the data of the Department of Labor and Employment in February 2011, in Moscow alone the database of the city employment service offered more than 150 thousand vacant positions – three times more than the number of unemployed people registered in the capital [19].

The impression dominating Russian society, that financial reasons are the key factors in the choice between Russian and foreign workers, does not reflect the reality of the Russian labor market.

A precise estimate of the needs of the Russian labor market in terms of specific professional and qualification categories and types of economic activity is even more difficult. To an extent, an opportunity can be found in the sample survey of enterprises undertaken by Rosstat once every two years. The last survey was conducted in autumn of 2010 [20].

As of October 31, 2010, the labor shortage of organizations explored in the survey to fill vacant positions was 619.5 thousand employees (as of October 31, 2008, at the start of the crisis, it had been nearly 900 thousand. The largest number of vacancies was registered in health care and social services (170 thousand); manufacturing industry (84 thousand); organizations dealing with real estate, lease and services (76 thousand), transportation and communications (72 thousand), and education (57 thousand).

The labor shortage is uneven across the Russian territory. As the average specific weight of the need in labor to fill vacant positions against the overall number of jobs in Russia was 2.1% in 2010 (2.8% in 2008), the Central Federal District indicator was 2.7% (out of 620 thousand vacancies one third of that number was registered therein, while its share in the overall number of employed was only 26% in the industries explored by Rosstat). The leaders in labor shortage in the Central Federal District are Moscow at 4.3%, the Moscow Region at 3.3% and the Kaluga Region at 3%. The relevant indicator of the Northwestern Federal District is also higher than the Russian average – the share of vacancies in the overall number of jobs is 2.6%; inside the District the most disadvantaged are the Murmansk Region (4%), Saint-Petersburg (3.2%) and the Leningrad Region (2.7%). Those two were the ones worst hit by the crisis: the Central and Northwestern Districts featured a highly substantial decline of the indicator as compared to 2008 (the share of vacant positions in the aggregate number of jobs went down by nearly 30%). The indicator remained stable in the Far Eastern Federal District – the share of vacancies in the overall number of jobs was 2.9% (as in 2008), i.e. by 2010 the region became the actual leader in the relative shortage of workers (naturally, the absolute indicator of vacancies in the Far East is significantly lower than in the Central and Northwestern Federal Districts – 30 thousand, 207 thousand and 81 thousand jobs).

As regards professional and qualification categories, the highest requirement is to be found in the category of highly skilled professionals (23% of the total demand); the second position belongs to a number of categories with nearly identical indicators of demand – skilled workers of industrial enterprises, construction, transport, communications, geology and mineral prospecting (17%) and specialists of average qualification (16%); the third place goes to unskilled labor (14%). At the same time, the specific weight of labor shortage in the overall number of jobs held by skilled workers and unskilled labor was identical and made 2,2% (i.e. exceeded the mean Russian indicator making 3.2% and 3.3% respectively). Within the two years between the surveys a less visible decline of the shortage was seen in catering and communal services, trade and related spheres of activity – only 14% (the overall shortage in 2010 was 31% less than shown by the 2008 survey); the specific weight of the demand in labor in the overall number of jobs in this category was one of the highest – 3%. If the Russian economy continues to follow the trend of the majority of developed countries, the percentage of workers engaged in services would show grow to outpace the rest, while the demand for such laborers would become even higher.

Apart from the official statistics and sample surveys of Rosstat, the results of public opinion polls of employers allow an indirect assessment of unfulfilled needs in workers in different segments of the Russian labor market. According to one of the polls [21], in 2010 about 30% of employers had vacant positions in their enterprises [22]. The enterprises equally needed highly skilled and medium-skilled specialists (more than half of employers announced a shortage), and approximately one fifth felt short of unskilled labor.

A shortage of manpower makes employers seek the services of labor migrants: according to the polls, about a quarter of Russian companies failed to fill the available vacancies with local workers (Table 1). However, the indicator was largely different in various fields of business activity. For example, nearly one half of construction companies claimed that their vacant positions could not be filled with locals; in transportation and agriculture, approximately one third of companies said the same.

Table 1.“Do you believe you can find local workers (residents of your region) to fill the vacant positions you currently have?” (% of respondents)

| Able to find local workers to fill all vacant jobs | 75 |

| Able to find local workers to fill some of vacant jobs | 12 |

| Impossible/very hard to find local workers | 10 |

| No answer | 3 |

| Total | 100 |

Source: All-Russian survey of enterprises and organizations (Russia Public Opinion Research Center, VCIOM, 2010).

With a fair share of certainty one can presume that, because of the loss of able-bodied population, in the immediate future the share of vacant positions which cannot be filled with local workers will only grow and, consequently, the need in foreign labor among employers will only increase.

From the employers’ viewpoint, the most problematic issue is the selection of local workers to fill the vacancies of highly skilled labor - this opinion is shared by 32% of corporate respondents. Recruitment of local workers to unskilled labor jobs and positions of medium-skilled labor causes less concern among employers; however, 9% and 11% of the respective polls' participants emphasized the problem.

Judging by the results of the second round of the same VCIOM opinion polls (covering 450 enterprises and organizations employing foreign labor), as well by the analysis of the result of focus groups held with the employers [23], it is strongly evident that in the current environment the employment of foreign workers by Russian enterprises is an objective necessity. The essential reasons for attracting foreigners are structural, and reflect both the shortage of labor force and the imbalance of the Russian labor market.

Such reasons as the shortage of Russian manpower, both skilled and unskilled, the disparity in supply and demand of workers of certain professional and qualification categories (“Russian workers refuse to take difficult, dirty and unskilled jobs”, “we feel short of skilled Russian employees” etc.) together with the deficiency of flexible employment strategies needed by the employers (for instance, a ban on seasonal employment of local laborers) were emphasized by 90% of respondents. All this demonstrates that nearly all companies employing labor migrants had objective structural reasons to do so, instead of economy and profit motivations as is often assumed by the public opinion.

Another important reason to hire migrants is the quality of their work, which is often higher when compared to Russian performance, as well as discipline and, not least, abstention from alcohol. All in all, only one third of employers declared purely financial reasons for hiring foreign workers – seeking to economize on remuneration, overtime pay, social and pension deductions, sick leave and annual leave [24]. However, one has to point out that small businesses view those reasons much more seriously than medium-size and larger businesses. This can likely be explained by the more difficult environment in which small businesses operate, making them economize on everything, and primarily on the salaries of their employees.

In general, the larger is the turnover of an enterprise and the higher its own estimate of its financial status, the less importance the employers attach to economizing on migrants’ salaries.

Thus the impression dominating Russian society, that financial reasons are the key factors in the choice between Russian and foreign workers, does not reflect the reality of the Russian labor market.

***

The main outcome of the last decade in the field of labor migration can be seen in the concord eventually reached between the expert community and decision-makers on labor migration's necessity for the development of Russian economy. The next step is the resolution of other, more sophisticated issues. First among them is assessment of the number and skills of labor migrants needed in Russia. Given the lack of actual mechanisms for assessment of the quantitative needs of the Russian labor market as regards workers in general and migrants in particular, and ones further subdivided by specific professions and qualifications at that, the task cannot be accomplished without special in-depth research.

Furthermore, as of today we are unaware of the total number of labor migrants already staying and working in Russia. One cannot obtain statistically valid data on their aggregate number without a substantial reduction of the illegal segment of labor migration. In other words tangible legislative measures need to be taken in order to bring foreign workers out of the shadows. In part, those measures are already provided for by the drafted and adopted Concept of the state migration policy of Russia through the period up to 2025.

Notes:

1. Hereinafter in speaking of labor migration into Russia we imply external labor migration, i.e. temporary migration of economically active nationals of foreign countries to Russia for the purpose of employment on its territory. Consequently, a labor migrant or an employed migrant is a person who will be, is, or was engaged in remunerated activity in a state he/she is not a citizen of (UN International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, Part 1, Article 2).

2. Mukomel V. Economics of Illegal Migration in Russia // Demoscope-Weekly. 2005. № 207–208. June 20 – August 14. URL: http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2005/0207/tema01.php

3. Zhanna Zaionchkovskaya. Ten Years of the CIS – Ten Years of Migration among Member States. Deposcope-Weekly, # 45–46, December 2001. URL: http://demoscope.ru/weekly/045/tema01.php

4. URL: http://www.baromig.ru/arrangements/proshedshie/itogi-ekspertnogo-soveshchaniya-9-aprelya-2010-g.php

5. Population of Russia 2008. 16th Annual Demographic Report / Managing Editor А.G. Vishnevsky. М., Higher School of Economics Publishers, 2010. P. 265

6. Regnum, March 21, 2012

7. Migration and the Demographic Crisis in Russia / Ed. Zh.A.Zayonchkovskaya, Ye.V.Tyuryukanova. М.: MAKS Press, 2010. P. 10

8. Certain experts point out that the migration reform intended to legalize the largest possible number of migrants began stalling even before the crisis because the managing staff was unprepared for a liberalized migration policy, and because popular support was weak. (Population of Russia 2009. 17th Annual Demographic Report / Managing Editor А.G. Vishnevsky. М., Higher School of Economics Publishers, 2011. P. 263

9. For example, Order of the FMS of Russia of February 26, 2009 # 36 “On Certain Aspects of Issuing Work Permits to Foreign Nationals Arriving in Russia under Visa-Free Procedure”, according to which a work permit was initially issued to a labor migrant for the period of 90 days; upon its expiry a new work permit was issued (upon presenting a labor contract) for a period no more than one year (in fact, not more than nine months, as the first permit was valid for three months) since their entry to Russia. The “long-term” work permit indicated a specific employer who signed the labor contract presented by a migrant to the migration service (i.e. once again actual practices “attached” a migrant to a specific employer).

10. Regrettably, it is impossible to give an objective judgment of whether the migrants with formalized patents are actually working for private individuals, or whether they made use of an opportunity to extend their migration registration through a patent (while continuing to work with legal entities) – the problem requires special research.

11. Legal Employment of Foreign Work Force on the Territory of the Russian Federation in 2005–2008. Analytical materials based on official statistic reports of the FMS of Russia and Rosstat. Migration 21st Century Foundation. Moscow, 2009

12. URL: http://www.baromig.ru/arrangements/proshedshie/itogi-ekspertnogo-soveshchaniya-9-aprelya-2010-g.php

13. Hereinafter we use data from sample opinion polls among migrants conducted by the Center of Migration Research in 2008-2010: they recognize insufficient knowledge of Russian when visiting shops or drugstores; about one half finds difficulties when formalizing their documents.

14. Migration and the Demographic Crisis in Russia / Ed. Zh.A.Zayonchkovskaya, Ye.V.Tyuryukanova. М.: MAKS Press, 2010. P. 37–38

15. URL: http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2007/0277/analit02.php; URL: http://www.strana-oz.ru/2003/3/trudovaya-migraciya; URL: http://www.un.org/russian/news/fullstorynews.asp?newsID=11550

16. According to the data of a sample poll of enterprises and organizations conducted by the VCIOM in 2010, 62% of employers confirmed that they fail to notify employment services about open positions at the enterprise.

17. "Enterprises of the informal sector shall be considered those household enterprises or non-corporate enterprises owned by households producing commodities or services for marketing, and not holding the status of a legal entity" (Methodical Guidelines on Measuring Employment in the Informal Sector of Economy. Goskomstat of Russia, 2001).

18. Gimpelson V. Informal Employment in Russia // Deposcope-Weekly. 2003. # 107–108. 31 March – 13 April. URL: http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2003/0107/tema01.php

19. URL: http://www.labor.ru/index.php?id=1465

20. The subjects of the survey were organizations (except small businesses) engaged in all types of economic activity with the exception of organizations with a core focus on financial activity, state management and national security, social insurance, activities of public associations and ex-territorial organizations. In 2010 the survey covered 56 thousand entities. The overall number of workers on the payroll was 28.6 million people. For more details see: “On the Number and Requirements of Organizations in Employees per Professional Groups as of October 31, 2010 (based on the sample research of the Rosstat). URL: http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/2011/potrorg/potr10.htm

21. An all-Russian poll was conducted by VCIOM in April-May of 2010. The sampled population represented organizations of different size and types of activity; the sample covered 1500 enterprises in 47 Russian regions (the poll incorporated major enterprises, medium-size and small businesses). The sampling error does not exceed 2.5%.

22. On average, 18 vacancies were registered per each small enterprise, 20 vacancies each for medium size businesses and 64 vacancies each for large enterprises. Nearly 50% of employers from big businesses declared available vacant positions. Source: All-Russian poll of enterprises and organizations (VCIOM, 2010).

23. In 2009 the Center for Migration Research conducted two focus groups attended by employers hiring foreign labor from the CIS countries, in Moscow and in Sochi. Each focus group brought together 8-10 representatives of respective enterprises. These were primarily heads of companies (small businesses) or HR managers (medium and major businesses). They represented practically all industrial spheres employing migrants: construction, communal services (Moscow), catering, trade, industry and transportation.

24. One has to point out that the tax laws amended in 2009 “played right into the hands” of foreign workers by relieving their employers from a substantial part of the wage fund tax paid to insurance funds. From that time on, the tax on a Russian employee has been several times higher than the one levied on a foreign worker. The logic of the decision is beyond comprehension.

(votes: 2, rating: 5) |

(2 votes) |