Russia and Georgia: Economic Interaction

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Head of Department of Economic Policy and Public-Private Partnership at MGIMO-University

In the modern world, resolving political differences is increasingly dependent on the incentives that economic partners have to cooperate. After a long period of an almost complete suspension of any economic relations between the two countries, Russia and Georgia have now been given a chance to build a new system of economic collaboration based on their respective geo-economic and geopolitical interests.

In the modern world, resolving political differences is increasingly dependent on the incentives that economic partners have to cooperate. After a long period of an almost complete suspension of any economic relations between the two countries, Russia and Georgia have now been given a chance to build a new system of economic collaboration based on their respective geo-economic and geopolitical interests.

Preconditions for Improving Bilateral Relations

Georgia has been in the spotlight of Russia’s political and economic focus for quite a while, going back to as early as the 15th century when official diplomatic relations between the two countries were first established. The region started featuring particularly highly on Russia’s agenda at the start of the 19th century when the Caucasus became a key region for the countries in the neighborhood which were all set on expanding their territories. With almost all of the Trans-Caucasus incorporated in its territory, the Russian Empire created a single social and economic system and significantly strengthened cultural and economic relations between the two peoples. These relations withstood the disintegration of the empire that caused dramatic national and political conflicts in the region, including, in particular, the Battle for Tbilisi. In 1922, Georgia was incorporated within the USSR first as part of the Trans-Caucasian Socialist Federative Republic and then became a separate Soviet republic in 1936.

With serious problems in bilateral relations starting to emerge in the late 1980s-early 1990s, over the past three decades the two countries have faced some dramatic conflicts, trade-related, economic as well as political, that have culminated in the use of armed force. Russians and Georgians voiced reciprocal claims in the years of 2004-2006, and an ethnic conflict involving Georgia, Abkhazia and South Ossetia erupted in August 2008. As a result of all these problems, all economic relations between Russia and Georgia have virtually ceased to exist.

Bilateral relations today between Russia and Georgia are affected by three opposing factors: first, anti-Russian sentiment fuelled by propaganda, in particular in the aftermath of the 2008 conflict; secondly, historical and cultural affinities shared by the people of the two countries; and, thirdly, the economic benefits of mutual cooperation.

There is a pressing need to structure economic relations on a new, mutually advantageous plane that takes into account the interests of all the parties involved. What is needed is insight into the long-term geo-economic priorities of Russia and Georgia.

Key Areas for Collaboration

As in many other post-Soviet countries, the one obvious key area of interest concerns the energy sector. Importantly, this is not limited to supplies or the transportation of energy resources but rather offers opportunities for developing Georgian reserves that have remained of late largely unexplored. Various estimates suggest that Georgia has about 400 mln tons of coal, 580 million tons of oil and 98 bln cubic m of gas [1].

There is evidence, on the one hand, of a shrinking Russian presence in the energy sector. Russia had for a long time been the key supplier of gas to Georgia, but by the late 2000s, Georgia set out to reduce its gas purchases from Russia, relying instead on increased imports from Azerbaijan. The key stated reason was the increase in the gas price. In addition, Georgians repeatedly claimed that they were unreasonably overcharged (in 2007, the price for Georgia was quoted at USD 235 per cu. m compared to USD 110 offered to Armenia) [2].

In the early 2000s, a hope emerged that cooperation in the energy sector could be raised to a new level owing to the participation of Russian business in Georgia’s gas distribution sector. The relevant examples included the establishment of the gas distributer, a joint-stock company Itera-Georgia (fully owned by Russian Itera), to supply gas to over 100 Georgian enterprises, including more than 30 regional gas distributers. However, in 2012 the company was acquired by Azerbaijan’s SOCAR, which is now the only retail operator in Georgia (except in Tbilisi) [3].

On the other hand, there are examples of improvements in, mutually beneficial bilateral cooperation. Of relevance here is the business of Lukoil’s subsidiary, Lukoil-Georgia, which owns an oil terminal in Tbilisi and a controlling stake in the oil terminal in the Mtskheta District. In addition, through its large chain of petrol stations, this company owns up to one quarter of the retail diesel and petrol market [4].

The electricity generation and distribution sectors also have seen a noticeable presence of Russian businesses. The Russian company Inter RAO has a 75 per cent interest in Georgia’s largest electricity distribution company Tekasi; a 100 per cent share in Mtkvari Energy and a 50 per cent stake in Transenergy; it also manages two hydroelectric stations - Khrami GES-1 and Khrami GES-2, with an aggregate capacity of 240 MWt [5]. Overall, the Russian energy holding controls about 30 per cent of the generating capacity and 35 per cent of electricity sales in Georgia. There is a successful joint company, Joint Energy System GruzRosenergo, which supplies and distributes electricity as well as operates its transit (its equity is split 50:50 between Georgia and RAO UES of Russia) [6]. A major success was achieved with the 2011 Memorandum of Understanding between Russia’s and Georgia’s energy ministries about measures to support the parallel operation of the Russian Unified Energy System and Georgia’s energy system [7], as well as by the agreement on the parallel operation of electricity systems in Georgia and Russia, signed by Russia’s Federal Grid Company of the Unified Energy System, the System Operator of the Unified Energy System, and the Georgian State Energy System [8].

There are also examples of technical cooperation in the energy sector. In particular, the Gardabani gas turbine thermal power stations owned by Energy Invest (Russia’s VTB project) installed two combined-cycle gas turbines at the Tbilisi regional power station. Russia’s VTB bank acquired 77 per cent of the shares in VTB Bank Georgia, and financed the USD 40 mln purchase of two Pratt and Whitney gas turbines for the Tbilisi power station [9].

In addition, Russian companies today seem to be eager to participate in the development of Georgian mineral deposits. To give an example: the Russian company Industrial Investors used its UK subsidiary, Stanton Equities Corporation, to acquire control over 97.25 per cent of the shares in the mining operations of Madneuli [10] and 50 per cent of the shares in the Trans Georgian Resources exploration company [11].

There is yet another promising and traditional area of bilateral trade links: the food industry. Serious differences between the two countries in that area started in 2005 when due to violations of phytosanitary rules, Russia introduced restrictions on Georgian agricultural produce, followed by a ban in 2006 on the import of wine, brandy and sparkling wines. According to various estimates, exporters of these products suffered losses between USD 300 and 500 million [12].

As relations resume so are the supplies of traditional Georgian goods: wine, brandy, tea, tobacco products, essential oil plants, canned vegetables and fruit, and wild nuts. There are some Russian companies now operating in the Georgian food market, one of the more successful so far being Russia’s Vimm-Bill-Dann Food Products which acquired the local grape juice company, Georgian Products [13].

An important player in the alcohol market is the Russian company, Dionis Club, which acquired Tiflis Wine Cellars from the Akhasheni Winery [14].

There are also cases of mutually beneficial cooperation in other food industries. Russia’s Mikoyan Meat Factory and Anagroup set up a joint venture, Mikana, producing meat products under the Mikoyan brand [15].

Additionally, Russian companies have an interest in Georgia’s telecommunications sector. In particular, Russia’s Vympelcom owns 51 per cent of shares in Mobitel and controls about 13 per cent of Georgia’s telecom market [16].

But in spite of the gradual resumption of trade and economic links, it is still too early to assume there is fully-fledged cooperation in place between Russia and Georgia. Russia’s place remains quite insignificant in both commodity and capital markets in Georgia.

Russian-Georgian Trade Cooperation

Trade today is being regulated primarily by the Agreement between the Government of the Russian Federation and the Government of Georgia on the underlying principles of customs administration and monitoring of trade in goods (2012). Until such a time when diplomatic relations are resumed, a neutral Swiss operator SGS has been invited to oversee. However, according to 2012 data, the share of Russian goods in Georgian imports remains quite insignificant: the EU accounts for 31 per cent, Turkey, 17.8, and Azerbaijan, 8.1 per cent, while Russia has a meagre 7.3 per cent [17]. By comparison with the period prior to the 2008 conflict, Russia’s share has dropped almost three times virtually across all of Russia’s export commodity groups. However, the key challenges lie not so much in dwindling Russian exports to Georgia and the loss of opportunity for Russian businesses, as in the competition from third-country companies which have strengthened their positions in Georgia. China and Turkey have so far proved most active in supplying Georgia with almost all of the goods that used to be traditionally imported from Russia.

Russian Goods as a proportion of Georgian imports (2012, %) [18]

| Commodity Groups | % |

|---|---|

| Total, of which: | 6 |

| Food and livestock | 18,9 |

| Cereal | 44,5 |

| Beverages and tobacco | 15,6 |

| Mineral fuel, lubricants and similar goods | 11,7 |

| Vegetative and animal fat, oils and wax | 14,3 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 20 |

| Machines, equipment and transport vehicles | 4,3 |

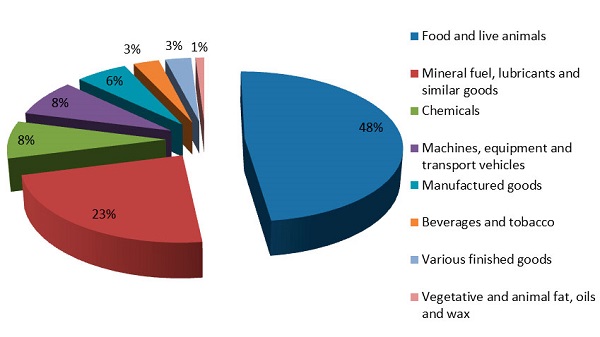

The qualitative structure of trade between Russia and Georgia has been changing too. While in the early period of Georgia’s independence, energy made up more than 50 per cent of total Russian exports, today it accounts for slightly more than 20 per cent, with gas dominating. While the energy trade is dwindling, there is a higher proportion of food products in the trade which increased from 8.2 per cent in 1995 to 48 per cent in 2011 (however, the 2011 absolute values are significantly below those of 2007). Interestingly, over 60 per cent of all supplies of food products to Georgia are cereals and related products [19]. So, it is appropriate to conclude that Russia and Georgia have retained trade links only in those commodity groups (gas, oil, electricity and cereals) that are key to national security and that, if largely discontinued, could have serious negative implications for the economy.

Russian Export to Georgia by Commodity [20]

There is a similar situation occurring in capital markets. Russian companies have been fairly successful on the Georgian market but the proportion of Russian capital in Georgia’s total foreign investment stock is still modest. The key investors in Georgia, based on this indicator, are the EU (42.7 per cent), Turkey (7 per cent) and the US (6.6 per cent). Russia, which is rated 6th in the total investment, has only 3.7 per cent, which is roughly the same as committed by international organisations [21]. Statistically, the share of Russian investment in Georgia has almost halved during the past decade. Noteworthy is the fact that, according to some exporters, the actual size of Russian capital on the Georgian market is significantly higher, meaning that the official statistics fail to reflect the share of Russian capital that comes via Cyprus or Virgin Islands. Also, according to Bank of Russia estimates, trans-border transactions by individuals amount annually to up to USD 0.8 bln [22].

Prospects for Bilateral Cooperation

Russian investors are represented rather broadly across Georgian economic sectors, and they are all quite unanimous in arguing that Georgia offers good prospects for Russian businesses both on the financial market and in the real sector of the economy, virtually in all commodity and trade groups, provided the political conflict between the two countries is resolved. The more promising sectors include meat and meat products; drugs and pharmaceuticals; iron and steel; and motor vehicles.

The call of the day today is to assess the opportunities for the further development of Russian-Georgian economic relations. To do that, it is essential to define the key areas of future cooperation, assess the current and potential challenges and threats, and find ways to overcome them.

Nana Gegelashvilii

новых путей развития.

Russian-Georgian Relations – Continued

Stagnation or Positive Progress?

Given the current status of bilateral relations, it may be appropriate to focus on enhancing and promoting the already existing links, with their smooth operations and reliable collaboration. In terms of trade, Russian businesses are quite competitive in dairy products, poultry, fuel and electricity supplies. On the other hand, Russian consumers are quite comfortable with such traditional Georgian goods as wines, tea, fruit, essential oils and related products.

Going forward with bilateral trade, industries that might need more time to cultivate include manufacturing industries, for instance, machines, transportation vehicles and agricultural equipment; chemicals, e.g., lubricants and mineral fuel; and also tobacco and animal-derived products. One can, logically, expect that investment cooperation will be developing along the same lines.

There are some promising areas of note. Cooperation ought to be enhanced in those sectors that have been effective so far: gas, exploration of mineral resources, energy, petroleum refining, food, telecommunications, and finance.

Of particular note is also the services market. Traditionally, tourism has always been the most promising area in services. By the end of the 2000s, tourist exchanges between the two countries were practically non-existent. However, following the unilateral abolishment of visas by Georgia, the number of Russian travellers has increased considerably. During the first visa-free year alone, their number grew by 75.5 per cent [23].

It has to be remembered nevertheless that there are a whole range of issues that restrain opportunities for further growth in bilateral relations. Russia, in particular, should be aware of the significant growth in joint Chinese-Georgian projects and of the high volume of investment by the US and Turkey. With the competition growing, Russia should either initiate new, more profitable and competitive projects, or facilitate multilateral cooperation, by joining existing or proposed programmes.

It is however apparent that it is the resumption of political ties between the two countries that will play the decisive role in the future of Russian-Georgian relations, be it in trade or investments. Unless the two countries enjoy stable, good-neighbourly relations, their mutual trade can hardly be expected to grow.

Understandably, this will take a lot of time. The Voice of America agency claims that 63 per cent of the Georgian population continues to perceive Russia as a source of political and economic threats to Georgia. At the same time, according to the same source, 82 per cent of Georgians are fully supportive of improving the dialogue with Russia.

Resuming political relations would require, apart from high-level talks, a people-to-people dialogue. According to the Russian statistics authority Rosstat, there are about 157,000 Georgians residing in Russia, which is almost 40 per cent of the Georgian diaspora abroad. On the other hand, every third resident of Georgia can speak Russian [24]. By improving interaction in this area and, among other things, by enhancing cultural exchanges, it will be possible to achieve the mutual promotion of goods and services and increase reciprocal financial flows.

Despite the fact that trans-border cooperation may play a rather significant role in promoting better bilateral relations, there has been little progress in that area. There is limited cooperation between Russia’s Rostov region and North Ossetia and the neighbouring regions in Georgia, and the great potential of such collaboration has remained practically untapped.

More should be said about the need to resume proper transport communications. Following the resumption of motorway traffic, the most relevant projects will be the modernization of the Georgian Military Road and the resumption of direct regular flights. Significantly, Georgians so far have been actively exploiting options for transportation corridors obviating Russia. One of such projects is the Baku - Tbilisi - Kars railway connecting the three countries without involving railways of the former USSR.

It is obvious that although at the moment Russia and Georgia enjoy very little cooperation in the economic real,, with an appropriate structuring of bilateral relations both countries can now hope for some positive developments. The opposition party Georgian Dream winning the 2012 parliamentary election and the subsequent dialogue between Bidzina Ivanishvili and Dmitry Medvedev at the Davos Forum in January 2013 seem to present new opportunities for a Russian-Georgian dialogue.

1. Economic status of Georgia [on the internet]/ Information Agency “Mir Nauki”. Moscow, Mir Nauki, 2012. - Accessed: http://worldofscience.ru/geografija-mira/19-geografija-gruzii (in Russian)

2. International Electronic Data Base on Trade / UNCTAD (UN Conference on Trade and Development) // The official web-site of UNCTAD (UN Conference on Trade and Development): Geneva: UNCTAD, 2013. Accessed: http://unctadstat.unctad.org

3. http://newsgeorgia.ru/economy/20121101/215306679.html

5. http://www.blackseanews.net/read/15755

6. http://www.fsk-ees.ru/about/subsidiaries/subsidiaries_of_ojsc_quot_fgc_ues_quot_with_shares_in_authorized_capital_from_20_to_99/ao_eco_quot_gruzrosenergo_quot/

7. http://minenergo.gov.ru/press/company_news/14600.html?sphrase_id=585294

8. http://www.fsk-ees.ru/shareholders_and_investors/ir_releases/?ELEMENT_ID=2200

10. http://www.prominvestors.com/projects/completed/madneuli-kvartsit/

11. http://polpred.com/?ns=1&ns_id=26431

12. See, e.g., http://txt.newsru.com/finance/12sep2008/guuuuam.html or http://polpred.com/?cnt=47&ns=1§or=22&page=8

13. http://www.dairynews.ru/news/quotvimm-bill-dann_ppquot_prodal_quotgruzinskije_p.html

14. http://rosalcohol.ru/site.php?id=6237&table=bmV3c19nbGF2

15. http://polpred.com/?ns=1&ns_id=77849

16. http://novoteka.ru/event/2211516

17. http://georgiamonitor.org/detail.php?ID=538

18. International Trade Centre, accessed: http://www.trademap.org/tm_light/Bilateral.aspx

20. According to UNCTAD (UN Conference on Trade and Development) // The official web-site of UNCTAD (UN Conference on Trade and Development): http://unctadstat.unctad.org

21. National Statistics office of Georgia. Tbilisi: National Statistics office of Georgia, 2013. Accessed: http://www.geostat.ge

23. http://www.police.ge/index.php?m=199

24. B. Murashkin. Georgian public asks to return the Russian language to schools. Murashkin B. // Golos Rossii web-site, 7 February 2014. Accessed: http://rus.ruvr.ru/2014_02_07/V-Gruzii-obshhestvennost-prosit-vernut-russkij-jazik-v-shkoli-0932/

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |