More than ten years ago, in February 2011, the Arab Spring began in Libya. The armed uprising quickly escalated into an armed conflict that had Muammar Gaddafi overthrown. Since then, the civil war has not stopped in the country. At the heart of the current conflict in Libya is the confrontation between the Government of National Accord (GNA), located in Tripoli, and the Libyan House of Representatives, located in Tobruk. The government in Tobruk is supported by the Libyan National Army (LNA) led by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar. In April 2019, the LNA attempted to seize Tripoli, but it was forced to retreat following months-long siege of the city.

Current developments

2020 was marked by unprecedented efforts by international organizations, world powers and regional players, as well as attempts by both sides of the Libyan conflict, to resolve it by political means. On January 19, 2020, an international conference was held in Berlin, the participants of which called for the disarmament of all paramilitary groups and devised specific mechanisms for controlling the arms embargo. However, neither the conference resolution nor the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic led to—at least—a cessation of hostilities.

On October 23, 2020, representatives of the GNA and LNA signed a ceasefire agreement in Geneva, which the UN labelled historical. In November 2020, the Joint Military Commission, composed of representatives of the warring parties, agreed on practical steps to implement the agreement. In particular, agreement was reached on the creation of a military subcommittee to monitor the withdrawal of troops. On December 27, 2020, an official Egyptian delegation arrived on the first visit to Tripoli since 2014, where they discussed the prospects for mending Libyan-Egyptian relations as well as the economic agenda and security issues. Parliamentary elections in Libya are scheduled to be held in December 2021. Besides, there was agreement to hold a referendum on the Constitution in 2021.

Some politicians, scientists, and representatives of the expert and analytical community are optimistic about an early settlement of the Libyan conflict, but many of their colleagues, on the contrary, are quite skeptical. On the one hand, the escalation of hostilities that began in April 2019 has indeed subsided. On the other hand, experience shows that setting any specific dates for the electoral processes in Libya and provisions for transparent mechanisms to establish legitimate government bodies do not mean that elections will be held and their results will be subsequently recognized.

When predicting what the Libyan conflict will be in the medium term, it is necessary to take into account that the war in Libya is an absolute disequilibrium system. While the existing trends are susceptible to change sparked by the course of how things unfold, the conflict may take on new trajectories.

Scenario I. Political settlement

The civil war in Libya has been going on for more than ten years, and there have been repeated attempts to come to a political solution to the conflict over this time. The hope that this will happen remains. The efforts undertaken in 2020 to reach national consensus may not have been in vain as they could become a solid foundation for a political settlement of the conflict. The country may well manage to hold all-Libyan elections, with the people who will come to power enjoying relative legitimacy, both in the eyes of the world community and among ordinary Libyans.

Libya has 44.3 billion barrels of proven oil reserves [1]. Cessation of hostilities will allow counting on Libya’s oil exports partially restored and, possibly, on new oil pipelines constructed. The long-awaited reconstruction of the transport infrastructure, oil production and oil refineries will ensue, which will play an instrumental role in the economic renaissance of the united Libyan state.

The new Libyan authorities will face a number of important tasks, including restoring production facilities, infrastructure and the housing stock of the country. Russian and foreign companies will have the opportunity to participate in the restoration of the Libyan state. At the meeting of the Minister of Industry and Trade of the Russian Federation with the Libyan delegation on January 28, 2021, they discussed not only the prospects for diversifying trade between Russia and Libya but also avenues for participation of Russian companies in restoring energy, agriculture, industry, social and transport infrastructure in Libya.

China will certainly show its interest in the post-war revival of Libya. The GNA has welcomed the possible participation of China in reconstructing the country’s infrastructure once the war is ended. Over the past few years, Chinese diplomats have repeatedly met senior officials from the GNA to ultimately sign a Memorandum of Understanding under the Belt and Road Initiative.

There will be an opportunity to resume the deliveries of Russian weapons to the country. However, although the economic situation in the country will stabilize, the Libyan leadership is unlikely to have enough financial resources to pay for military imports. Competition with manufacturers from Europe and the USA may lead to a forced decrease in export profitability [2].

At the same time, there is a strong imprint of tribal relations on the Libyan society [3]. Even if political peace is established in Libya, it will be quite fragile. The society will remain fragmented, which means that the risk of social tensions growing will remain. Extremist and terrorist organizations operating in Libya can use this to destabilize the situation in the country. Weapons proliferation (mainly small arms)—which for many years were virtually freely distributed throughout the country—will serve as an additional factor in a hypothetical social explosion.

Scenario II. Escalation

It is possible that the establishment of even a fragile peace in Libya will not take place at all. One of the possible scenarios may be another escalation of hostilities. There can be many nominal reasons for the opposing sides to bring forward mutual accusations. These range from provocations during the pre-election period to non-recognition of the results of electoral processes. As a result, this can lead to a sharp escalation of tensions.

As Stephanie Williams, head of the UN Support Mission in Libya, noted, every time the situation in Libya seems to have reached its lowest point there is a surge of violence. In September 2020, the UN announced that the LNA and the GNA—despite the relatively calm situation on the front line—will resort to receiving help of allies from abroad, thus accumulating modern weapons and military equipment. In two months, some 70 aircraft with suspicious cargo for the LNA landed at airports controlled by Khalifa Haftar’s army, and three cargo ships stopped in the ports in the east of the country. 30 aircraft and nine cargo ships delivered cargo for the GNA.

At a meeting on the Libyan political dialogue on December 2, 2020, Stephanie Williams announced that there are ten military bases in Libya that are fully or partially occupied by foreign troops and that host about 20,000 foreign mercenaries. The cessation of hostilities was used by the government in Tripoli and the LNA to cement their positions and enhance the combat effectiveness of their troops, including through assistance from abroad. In January 2021, it was recorded that the mercenaries were building a defensive line and fortifications—presumably, in order to repel a possible attack by the GNA troops on the LNA-controlled territory.

Against the background of the confrontation between Russia and the United States likely to intensify, the degree to which the conflict is internationalized may increase, much as the control over the arms embargo tighten and the role of private military companies as a foreign policy asset of individual states expand. Private military companies help reduce political risks that a state’s engagement in the war in Libya entails, while actively supporting one group or another by sending weapons, military instructors or mercenaries.

There is a danger of destroying the remnants of Libya’s oil infrastructure, the backbone of the country’s economy. Artillery shelling of residential areas will cause additional interruptions in water and electricity deliveries to Libyan cities. Illegal migrants attempting to enter the EU countries, especially Italy, will become more frequent.

The Republic of Turkey, which claims a leading role in the region and seeks to revive the “former greatness” of the Ottoman Empire, is sharply intensifying its actions [4]. Most likely, Ankara will support the government in Tripoli, not only with weapons, but also with troops, as it happened in January 2020. Egypt will continue to support the LNA, as it hopes this can minimize Libyan weapons being smuggled into Egypt. At the same time, the possibility of direct military intervention by Egypt remains extremely low. Even if Turkey sends large military units to help the GNA, Cairo will be reluctant to enter into a protracted military conflict, the outcome of which is unclear. Moreover, a direct military clash between Turkey and Egypt is practically impossible on account of their belonging to military and political blocs. Rather, in response to Ankara’s decisive actions in Libya, Cairo will deploy troops on the border with Libya or transfer part of its units to the LNA-controlled Libya’s eastern regions. However, the prospect of the Egyptian troops advancing further to the West seems unlikely.

Scenario III. Maintaining the status quo

Despite attempts by both sides to embark on political dialogue, official statements by representatives of the opposing sides contain aggressive, accusatory rhetoric. For example, in a video message to the delegates of the 75th session of the UN General Assembly, Faiz Saraj referred to Khalifa Haftar’s offensive in Tripoli in April 2019 as “a tyrannical attack of the aggressor.” In addition, he urged not to compare foreign support for the “militants of Khalifa Haftar” with the help provided to the government in Tripoli “within the framework of legitimate agreements.”

In today’s conditions, it will be rather difficult for the main political forces in Libya to organize the work of the central electoral commission and other bodies in preparation for the elections. Besides, it should be borne in mind that the GNA, the LNA and a number of independent armed factions operating in Libya can control the electoral processes and, if necessary, sabotage them. One of the parties may try to disrupt the elections altogether. At the same time, the escalation described in scenario II seems rather unlikely to occur, as the world community is paying greater attention to the war in Libya.

The war in Libya provokes conflicts in at least 14 countries in Africa and Asia, mainly due to weapons smuggling [5]. Despite the possible strengthening of international control, maintaining the existing balance of power in Libya will provoke new conflicts and serve as a hotbed of destabilization in the neighboring countries, such as Tunisia, Algeria and Egypt. Should the next plan for a political settlement of the conflict fail, Libya risks becoming another Afghanistan, close to Europe.

What of the Libyans?

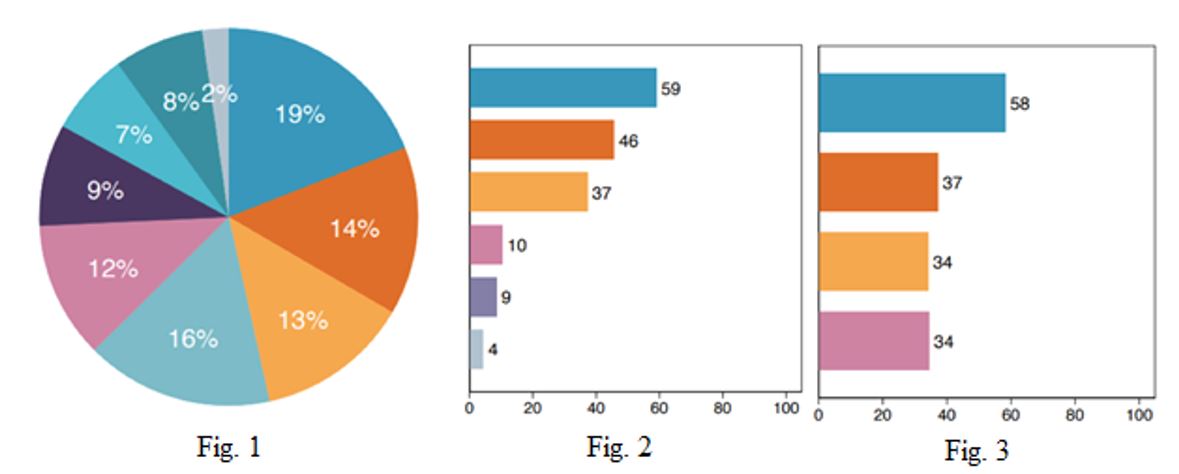

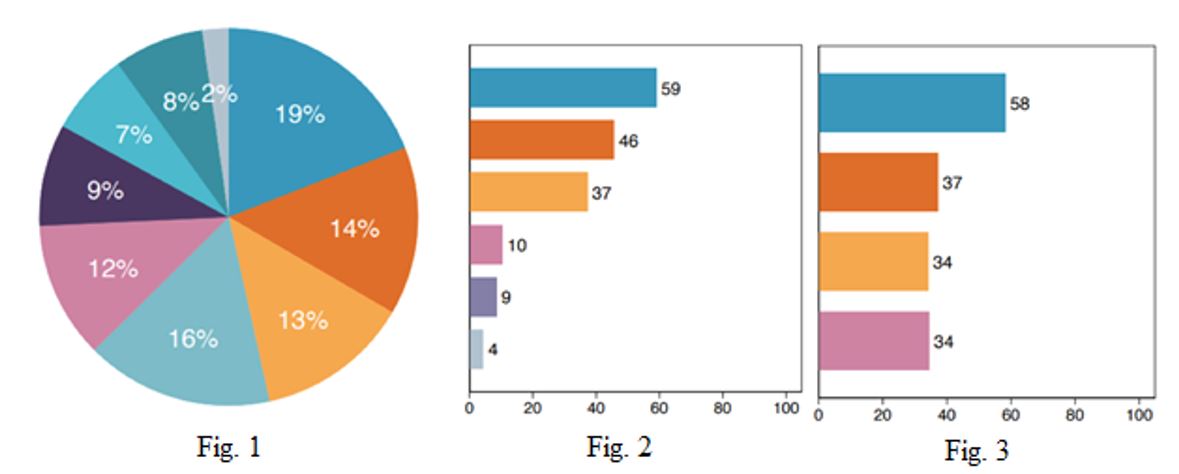

The last two scenarios seem to be the most likely. In 2019, the Arab Barometer [6] conducted a sociological study that clearly shows how Libyans themselves perceive the situation in their country and what they see as key problems [7].

Top challenges (Figure 1) cited include foreign interference (19%), fighting terrorism (16%), corruption (14%), security (13%), economy (12%), internal stability (9%) and political issues (8%) [8].

It also turned out that Libyans have little confidence in political institutions (Figure 2). Among the most trusted institutions are the army (59%), the police (46%) and the judiciary (37%), while the least trusted are the government (10%), parliament (9%), and political parties (4%) [9].

Figure 3 offers an interesting view of the surveyed Libyans on democracy. According to the polls, democracy is always the preferable political system (58%). At the same time, many rated democracy as indecisive (37%), unstable (34%) and bad for the economy (34%) [10]. With this in mind, it is possible that the Libyans are unlikely to trust their single government.

No matter how the conflict’s landscape changes, there is reason to believe that the Libyan society will in any case remain divided for quite a long time. Its further fragmentation will almost certainly occur against the backdrop of hostilities coupled with the pandemic and a decrease in Libya’s oil exports. Socio-economic problems will create additional space for radical sentiments growing. The Islamic State, Al-Qaeda and other terrorist organizations have high mobility as well as an ability to regenerate, which means that an attempt may well be made to revive a new Islamic Caliphate, albeit not as large as it is was a few years ago.

In the report of the Valdai International Discussion Club “The Middle East: Towards an Architecture of New Stability?”, Vitaly Naumkin, Scientific Director of the RAS Institute of Oriental Studies, and Vasily Kuznetsov, Head of the RAS Center for Arab and Islamic Studies, noted that the situation in Libya will affect the entire Maghreb in the foreseeable future [11]. It is almost certain that Libya and the neighboring countries will be overwhelmed by a new wave of radicalization. According to the Arab Center for Research and Political Studies report, 2% of Arabs have a positive attitude towards ISIS and other radical groups, with another 3% having an extremely positive attitude towards them. This is the highest percentage since 2014–2015 [12].

The situation in the region may aggravate, and it is necessary to increase effectiveness of the control over the transportation of weapons to and from Libya. In October 2020, the UN Security Council, chaired by Russia, adopted a resolution that extended the permit to inspect ships on the high seas off the Libyan coast. Indeed, this was the right step. With the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, humanitarian aid to Libyans also remains relevant, and it may include supplies of the necessary medical equipment to equip hospitals as well as personal protective equipment, of which Libya is now experiencing a shortage.

1. A. Fedorchenko, A. Krylov, D. Maryasis, N. Sorokina, F. Malakhov. The Middle East in the Focus of Political Analytics: Collected Papers: on the 15th Anniversary of the Center for Middle East Studies, 2019. P. 49.

2. Ibid. P. 452.

3. Ibid. P. 12.

4. V. Avatkov. Ideological and value factor in Turkish foreign policy [Vestnik MGIMO], 2019, no. 12(4). P. 124.

5. A. Fedorchenko, A. Krylov, D. Maryasis, N. Sorokina, F. Malakhov. The Middle East in the Focus of Political Analytics: Collected Papers: on the 15th Anniversary of the Center for Middle East Studies, 2019. P. 24.

6. Arab Barometer is a nonpartisan research network that provides insight into the social, political, and economic attitudes and values of ordinary citizens across the Arab world.

7. Libya Country Report /Arab Barometer V. 2019. P. 2.

8. Ibid. P. 3.

9. Ibid. P. 5

10. Ibid. 2019. P. 7.

11. V. Kuznetsov, V. Naumkin. Middle East: Towards a New Stability Architecture? 2020. P. 16.

12. The 2019-20 Arab Opinion Index: Main Results in Brief, Arab Center for Research and Political Studies. P. 58.