In recent years, Russian political elites and the expert community have been trying to rethink the conventional spatial categories and their substance in the main domains such as politics, the economy and security. Positioning Russia as one of the pillars of a polycentric world involves creating and promoting big ideas and narratives. In this context, the lack of clear-cut formulations can be seen as an invitation to dialogue with partners to jointly develop the conceptual foundations of the Eurasian space. Potential “dialogue partners” on these issues obviously also include India, which is designated in the Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation as one of the main (along with China) partners on the Eurasian continent. A delicate point here is that India is not in a vacuum, being an integral part of a complex subregional security architecture marked by military and political confrontation between two regional powers (India and Pakistan) and the involvement of external players, primarily China and the United States. In military and political matters, it is virtually impossible to sway the positions of political and military elites in South Asia as perceptions of their major concerns are not open to revision. Russia’s emphasis on ensuring security to accelerate economic development will allow the key stakeholders to step back from differences, focus on a positive agenda and at least start a dialogue on building a Eurasian security system.

Where do borders end?

In recent years, Russian political elites and the expert community have been trying to rethink the conventional spatial categories and their substance in the main domains such as politics, the economy and security. Yet the toponym “Eurasia” and its derivatives, which has become deeply ingrained in the Russian political vocabulary, is still characterized by vague (albeit very extensive) boundaries.

This suggests both pros and cons for the Russian foreign policy. Unfortunately, the ambiguity of the concepts used “erodes” the agenda, turning any discussion into a mix of toasts and perorations. On the other hand, positioning Russia as one of the pillars of a polycentric world involves creating and promoting big ideas and narratives. In this context, the lack of clear-cut formulations can be seen as an invitation to dialogue with partners to jointly develop the conceptual foundations of the Eurasian space.

The Russian leadership appears to be keeping exactly to this tactic. In his Address to the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation on February 29, 2024, the Russian President outlined the need to “work on shaping a new equal and indivisible security framework in Eurasia in the foreseeable future” and expressed readiness “for a substantive discussion on this subject with all countries and associations that may be interested in it.”

Another step toward starting this discussion was the overview of the cornerstones of “a vision for equal and indivisible security, mutually beneficial and equitable cooperation, and development” during the president’s meeting with senior Foreign Ministry officials on June 14, 2024. The “dialogue with all potential participants in this future security system” was listed as the first principle.

Potential “dialogue partners” on these issues obviously also include India, which is designated in the Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation as one of the main (along with China) partners on the Eurasian continent. A delicate point here is that India is not in a vacuum, being an integral part of a complex subregional security architecture marked by military and political confrontation between two regional powers (India and Pakistan) and the involvement of external players, primarily China and the United States. To evaluate how viable the Russian leadership’s concept of Eurasian security is in the South Asian context, let us consider each of the principles laid out.

Principle one: no objections

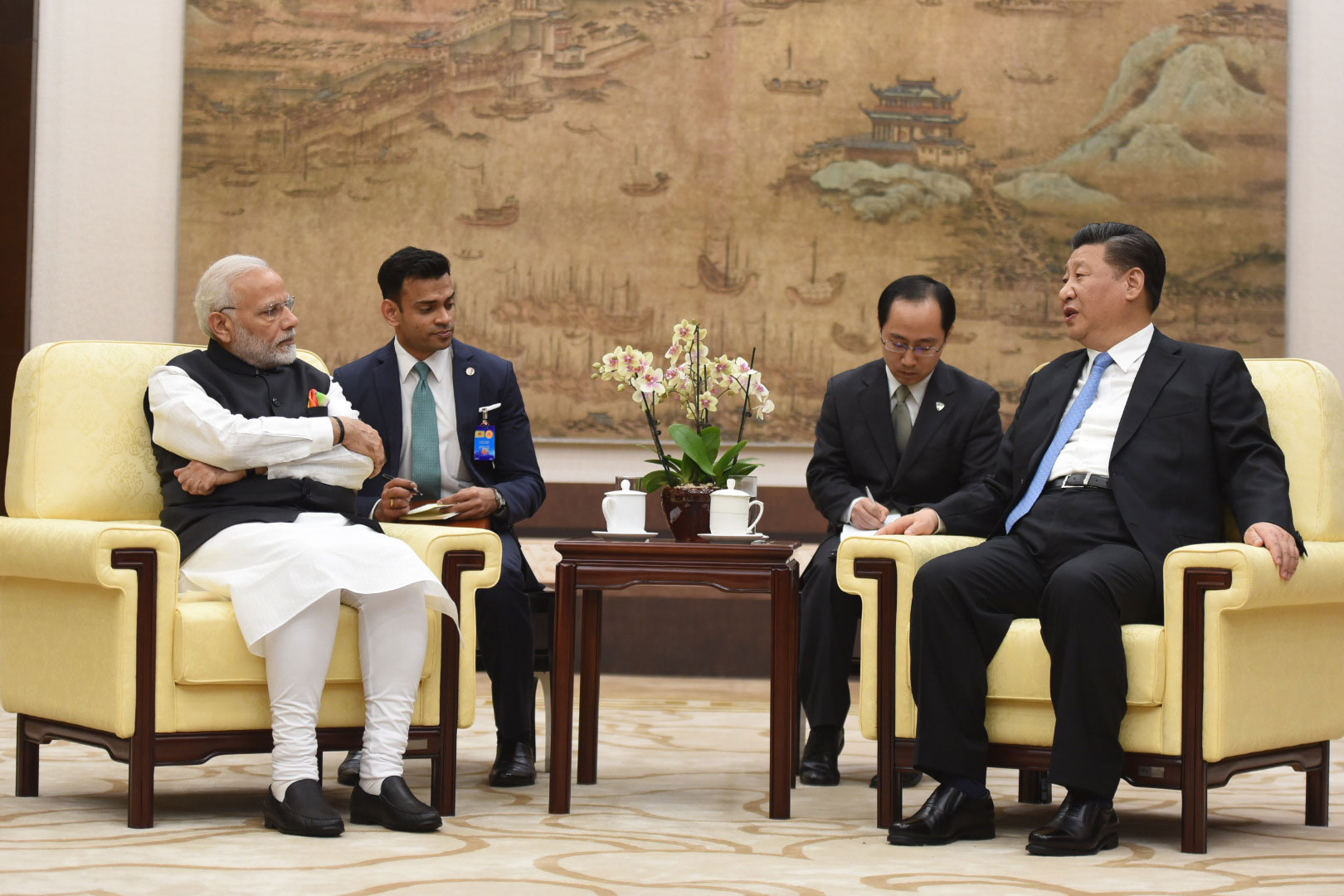

According to the Russian leadership’s idea, the parameters of the future security system should be coordinated with all stakeholders interested in constructive interaction with Moscow. Negotiations with Chinese President Xi Jinping are cited as the first success — the Chinese leadership felt that the Russian idea was complementary and consistent with the vision for global security promoted by Beijing.

In New Delhi’s eyes, this is not the best argument: Indian elites traditionally suspect China of building a “multipolar world and unipolar Asia” and are not ready to accept Beijing’s leading role in the future security system, also fearing the reinvigoration of China’s “military diplomacy.” Therefore, when further detailing its initiative, Russia should emphasize the absence of claims to any “exclusivity” for itself and other stakeholders, including India, because otherwise doubts will arise not only in Islamabad, but also in other South Asian capitals.

Principle two: geography is not dismissed

The second principle addresses the possibility of involving European NATO members in the future security architecture of the continent. This point seemingly has nothing to do with South Asia. But if we are talking about a common Eurasian security space, it is worth taking into account the specifics of the international regime in each particular subregion.

Let’s try to hypothesize: will Russia and European nations try to restore the institutional framework of the European security system that the parties have been working on since the end of the Cold War? Such discussions are likely to come up sooner or later. So, we assume that Moscow and European capitals will draw on their historical experience and try to work out an alternative to the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE Treaty) or to reanimate the OSCE. This scenario raises a key question: if we are seeking common principles for the entire Eurasian space, are South Asian countries and out-of-region players ready to adopt such a model?

In our view, this scenario is unlikely to unfold. The foundations of the Russian–European security dialogue were the product of a unique historical context of the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the ideas of a “common European home” encouraged the partners to perceive the CSCE/OSCE as a future regional “mini-UN.” [1] As we now understand, good intentions alone proved insufficient — the lack of timely institutional reforms rendered this platform incapable of preventing conflicts in Europe.

South Asia does not have even this unsuccessful experience to tap into. The problem is that the general principles of the defunct European security system are not applicable to this subregion — South Asian nations are used to relying only on themselves and their combined resources for security. Any restrictive commitments or the involvement of any third party in a conflict is seen as unacceptable.

In this vein, there is no hope that South Asian elites will be willing to learn for the experience of European security building. This means that Moscow would be better off engaging in a separate dialogue with NATO member states, which will help accomplish two objectives: to revive the currently dysfunctional mechanisms for maintaining security in Europe and to avert the paralysis of the Eurasian framework due to the unwillingness of Asian nations to adopt European experience.

Principle three: cooperation without confrontation

Stepping up contacts among existing multilateral organizations (the Union State, the CSTO, the EAEU, the CIS and the SCO) is fully consistent with the strategic culture of South Asian elites — participation in every possible format without strict commitments.

Of the above-mentioned platforms, only the SCO is directly related to South Asia, with India and Pakistan among its members since 2017. New Delhi and Islamabad take an active part in working on regional security issues and their bilateral disputes have not yet paralyzed this format. However, an important condition for the SCO’s further appeal should be the preservation of neutrality, i.e. preventing it from turning into a forum of states opposed to the West. This is particularly important for Indian elites interested in boosting investment and technological collaboration with Western nations, especially with the United States.

Principle four: minimization of external military presence

The gradual pullout of military contingents of external powers from the region is unlikely to raise any objections from South Asian capitals — New Delhi is traditionally wary of such practices, while Islamabad has a long and controversial history of interaction with foreign troops on its soil. But while Russia primarily implies the United States whenever it refers to “external powers,” for India the main external power in South Asia is China.

From the Indian perspective, it is Beijing that seeks to expand its military footprint in different Eurasian subregions, which is fraught with risks for India. In this context, the strength of the Russian initiative is that Moscow offers the main stakeholders to identify specific areas of cooperation in joint security, which would remove the issue of deploying military bases of “non-Eurasian” states from the agenda. Even though it is a long-term prospect, Russia’s proposals seem acceptable for South Asia.

Principle five: development goes first

In our opinion, the last principle put forward by Russia is the most attractive one not only for South Asian countries, but also for the whole of Eurasia. The nexus of security and economic development is relevant for all major centers of global politics and economy. For instance, modern Indian elites often recite the slogan “Together with all, development for all and the trust of all” («Sab ka sath, sab ka vikas, sab ka vishwas»). In this way, New Delhi demonstrates to external audiences its interest in global development and the country’s readiness for international cooperation, while assuring domestic audiences of its determination to provide the growing population with jobs and opportunities to improve their living standards.

In military and political matters, it is virtually impossible to sway the positions of political and military elites in South Asia as perceptions of their major concerns are not open to revision. Russia’s emphasis on ensuring security to accelerate economic development will allow the key stakeholders to step back from differences, focus on a positive agenda and at least start a dialogue on building a Eurasian security system.

1. Zagorskii A. Russia in the European Security Order. – Moscow, IMEMO, 2017, p. 16