Domestic Political Logic in US Foreign Policy

Barack Obama's address to Congress

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Ph.D., Senior researcher at IMEMO, Russian Academy of sciences

US-Russian relations are conflict-prone and unstable. Assuming that both Russia and the US have vested interests in developing a less conflict-prone and more predictable relationship, it is impossible to move forward without a proper awareness of the domestic political logic in either of the two countries, viz., the distribution of political forces, the process of decision-making, public opinion, and the electoral cycle. Which drivers of US domestic political life should Russia pay most attention to?

In 2013, the notorious scandal involving former NSA employee Edward Snowden, who asked the Russian authorities for political asylum, only further aggravated US-Russian relations, which by then had already been in relapse. The situation gave yet another reason to ponder the conflict-prone relationship between the two countries.

US-Russian relations are similar to a pendulum moving steadily along the same track. The amplitude of this pendulum can be predicted rather accurately in each specific case: we only need to understand the domestic politics angle in either of the two countries and to know the distribution of political forces, processes of decision-making, public opinion, and electoral cycle. A number of decisive factors drive the American domestic political logic.

Three Branches of Government and Their Powers

Each of the branches of government in the US has a distinct sphere of authority, but the efficiency of federal government depends to a large extent on the ability of the branches to accomplish certain joint functions. In real terms, this means that neither the federal budget nor an international treaty can become law unless they are signed by the President and approved by the US Congress. No promises that the US President makes while travelling overseas will become law unless they are endorsed by Congress. Similarly, no legislative bill passed by Congress will come into force unless signed by the President.

Bipartisan Government in the US

Apart from the President and Congress, the political process in the United States directly involves the two main political parties – Democrats and Republicans. These parties shape elections and the institutions of power at all levels; both the US president and Congressmen represent not only the executive and legislative authorities, respectively, but also the Democratic and the Republican parties. The US President’s electoral agenda is also that of the party he represents. Effectively, each victory or, even more, each defeat suffered by the President in the legislature can be turned into a victory or defeat for his party and cannot but reflect on both his image as well as on the standing of his party. Therefore, the party line and agenda are one of the decision-making drivers both in the executive branch and in Congress.

The Institution of Lobbying

Apart from official authorities and political groups, the US decision-making process intimately involves lobbying groups. Lobbying has been officially accepted as a political institution in the US, aimed at representing the interests that various societal groups may have. Lobbying has also been recognized by the legislature. In effect, lobbyists are conductors running along the American corridors of power.

Party Divide and Bipartisan Polarization

Since the early years of bipartisanship, both parties have adhered to an unwritten rule of an unconditional acceptance of the fundamentals of American society and the existing system, their key mission believed to be in maintaining, developing and improving this system.

Since the powers the US are so dependent on its public, every President’s agenda is centered on the most important topics to the public.

However, the views of the two parties on political process have recently come to diverge significantly. A stumbling block has emerged around the expansion of the government’s social functions as initiated by Democrats and opposed by Republicans. In the past two decades, political parties in the US have evolved from tools for resolving disputes between the competing branches of government into an additional point of conflict within the American political process. Apart from the fact that congressmen from opposing parties may never agree and bills are passed on a purely partisan basis, the President can reach an agreement with Congress only when his party has a majority in at least one of the chambers. In view of the bipartisan control over the branches of government, which has basically become a rule, the US President is finding it increasingly difficult to implement his agenda.

This effectively means that the President struggles to honor the promises he has pledged to the international community or the head of state in another country, as well as to his own people.

A More Conservative Public

The tragedy of 9-11 reinforced already strongly conservative sentiments in US society. These events were followed by the 2008 financial and economic meltdown which effectively divided the US public into right-wing conservatives, who argue that government should have as small a presence in the economy and society as possible, and left-wing liberals who demand social and economic fairness from government. This divide in society has aggravated the bipartisan radicalisation of power and further compounded the political process.

Logic of the Election Cycle

Members of the U.S. Congress stand for

the national anthem during a remembrance of

lives lost in the 9/11 attacks

The US has a classical election system where both congressmen and the President are elected by US citizens, and their political careers are dependent on the electoral attitudes of the public. The second presidential term directly hinges on the popularity of the President’s actions during his first term. In effect, during the first four years at the White House, the incumbent works towards reelection. In addition, his popularity will ensure his party’s success in the mid-term Congressional elections, and he therefore is working not only for his own victory but also for that of his party.

Congressmen cannot afford to make any important decisions without heeding the concerns of their voters. Since the House of Representatives is up for election every two years, campaigning on Capitol Hill never stops. The work of Congress is very transparent: most of its sessions are open to observers, and voting results by names are posted on the internet.

The Socio-Economic Agenda as Priority

Since the powers the US are so dependent on its public, every President’s agenda is centered on the most important topics to the public. The US public is generally more concerned by its social and economic well-being, while foreign policy issues appear to concern society only to the extent they affect the prospects for achieving such well-being. Hence, the majority of a presidential agenda focuses on social and economic issues. The popularity of the President and Congress and hence their re-election, depend on the implementation of socioeconomic and domestic political programmes.

This means in essence that domestic political decisions often become hostages to the internal political situation.

This means in essence that domestic political decisions often become hostages to the internal political situation. Why did President Obama have to sign the Magnitsky Act? If he had not, this document would have been perceived simply as a shot coming from US congressmen. However, President Barack Obama has a vast and important social programme that he would not be able to implement without the support of Congress, controlled largely by Republicans and with whom the Democratic president finds it difficult to negotiate. It may be easier to concede this rather minor issue in order to retain the chance of gaining support for the more important projects of his Administration.

These internal political innuendos were rather obvious in America’s foreign policy behaviour during the Syrian crisis that broke out in September 2013.

Having been informed about the use of chemical weapons against peaceful civilians in Syria, President Barack Obama announced that his country would not leave this act without retaliation and was prepared to resort to military sanctions, irrespective of what the international community might want to do. The US President then applied to Congress to seek its support of the White House.

Intelligence about the chemical attack in Syria had arrived not long before the beginning of the deliberations and endorsement of the budget for the new fiscal year. Given the bipartisan divide and polarisation, the bipartisan government makes the budget process an annual battle between Congress and the White House.

True, under the US Constitution, only Congress may declare war, this being the exclusive prerogative of the legislative power, since waging war is a joint function of the President and Congress. As Commander-in-Chief, the US President may make decisions about the course of a military campaign in line with the decisions of Congress. The President may also make the independent decision to start military action only in case of immediate danger to the security of the country. In 1973, the Constitution was amended through the War Powers Resolution, which now obligates the President to inform Congress within 48 hours about his intent to resort to military force. Should Congress decline to declare war, all troops must be returned to the US territory within 90 days. Section 8А of the Resolution states explicitly that the US President shall not have any additional powers apart from the ones conferred on him by the US Constitution.

However, in recent decades, the balance of power between the branches has shifted considerably in favour of the White House. Strong presidents dominate Congress, particularly as far as foreign policy is concerned, at times obviating the Constitution. The 1973 Resolution has been used by different US Presidents as a loophole to allow them to circumvent the Constitution for short-term military actions. Congress has repeatedly, but unsuccessfully, tried to dispute presidential actions, as in 1991 in the case of the Kosovo war.

President Obama, too, was accused of violating the Constitution and the Resolution when, in 2011, war actions in Libya continued in excess of 60 days without Congressional sanction. That is exactly the reason why President Obama went to Congress for support, strictly in compliance with the Constitution, caused such a powerful reaction among congressmen and in society.

Only internal political factors can help to explain the President’s adherence to the Constitution. Intelligence about the chemical attack in Syria had arrived not long before the beginning of the deliberations and endorsement of the budget for the new fiscal year. Given the bipartisan divide and polarisation, the bipartisan government makes the budget process an annual battle between Congress and the White House.

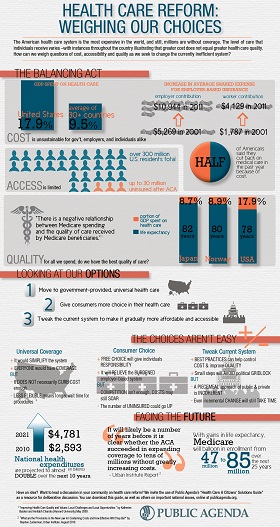

President Obama has already survived one such battle in summer 2012, and in 2013 the stakes were high over healthcare reform that the Democratic president had endorsed during his first term at the White House. But long before the budget deliberations, the Republican majority in Congress made it known that they intended to put the funding of President Obama’s health programme on hold. President Obama, in turn, long before autumn started, was looking for ways to increase the number of congressmen willing to support him.

Given the radicalization of both parties, and the party discipline observed like never before in these recent years, it is exceptionally challenging to ensure non-partisan support of bills. President Obama’s emphatic loyalty to the Constitution was expected to soften the more conservative Republicans. It was hoped that Congressmen would appreciate the desire of the President to play by the rules, rather than to support military action (as events in October later showed, this step was not enough to achieve a compromise on the budget).

In effect, neither the White House nor Congress wanted any military campaign, even a very limited one. It all came down to the electoral cycle and the priorities of his socio-economic agenda. Numerous polls conducted after Barack Obama announced his readiness to start a military action against Syria showed that 59 per cent of Americans were against any new military campaigns. Congress at the time was already thinking ahead to the 2014 election, and with the legislature’s record low ratings, even the most militant Republicans would not risk making a decision that voters would not support. President Obama is working currently for his legacy, as any second-term President would do, and his place in history hinges directly on his success in seeing through to the end the huge healthcare reform law that he had started. In that context, foreign policy acted as a bargaining chip for the President’s domestic policies.

Russia’s initiative during the Syrian crisis could not have come at a better time both for President Barack Obama and Congress as it relieved both parties of the need to take that last step, which, no matter what it could be, would not have won over the public, nor would it have been any help in addressing socio-political priorities.

For Russia, and for relations that have historically and to a large extent rested upon the leaders of the two countries, US domestic policies dictate the need to treat both the promises of US Presidents and the vociferous, not infrequently harsh and strong statements by US Congress equally sedately. To move from promises and statements to specific actions and bills, US government has to travel a long way through deliberation, approval, endorsement and signing. The political will of one of the branches is hardly enough to ensure that promises or statements are honoured, while Russia’s overly emotional response to such promises or statements would only fuel the sentiments and hardly help lobbying efforts for our country’s interests.

The political will of one of the branches is hardly enough to ensure that promises or statements are honoured, while Russia’s overly emotional response to such promises or statements would only fuel the sentiments and hardly help lobbying efforts for our country’s interests.

There is also an obvious need to distinguish between election rhetoric or political declarations and effective actions. The former become particularly loud before an election, a period during which one is well advised to wait before making any declarations in response, let alone take practical steps, particularly since anything that concerns Russia is extremely popular with right-wing politicians. It would be even less wise to expect any actions from US congressmen or presidents that might against the prevailing public mood.

Finally, the combination of all internal political factors also means that political decision-making in the US is vastly different from Russia’s. Russia’s “the President has said, the President will do” does not apply to America’s political life. Promises or declarations by the White House can only be relied upon as long as you take into account the constitutional division of powers, bipartisanship in the federal government, the electoral cycle, and public opinion.

More importantly, however, stable and mutually beneficial relations cannot be based solely on the personal relationship between the presidents. It is important to develop and expand collaboration with US congressmen both at the official level of inter-parliamentary exchanges and through more flexible tools such as lobby groups. It is imperative to constantly monitor the domestic situation in the US so that any action, when taken, is properly informed by a multi-faceted analysis of the layered and less than linear logic of the US political process.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |