Last May, the Eighth Ministerial Meeting of the Arctic Council was held in Kiruna (Sweden), with its main event the approval of a group of six states as permanent observers. China, which has demonstrated its willingness to participate in the exploration of the Arctic region more actively than the rest over the recent years, occupies a special position among them.

Norway has the last word

Norway’s stance on admitting China to the Arctic Council remained a matter of intrigue until virtually the last moment. This was due to the “cooling” of bilateral relations in the recent past, provoked by the Nobel Peace Prize Award [1] to Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo in early October 2010. At the time, Beijing took offense to the Norwegian Nobel Committee's decision and decided to “punish” Oslo on an official level by freezing all formal contact for a long time. Thus, on October 9, 2010, the Chinese side already suspended talks with the Norwegian Minister of Fisheries Lizbeth Berg-Hansen. She had arrived in Beijing to negotiate the reduction of customs duties (from 10% to 2%) for Norwegian salmon imported to China, which would guarantee annual savings of 380 million kroner for Norwegian exporters of fish products. In December 2010, the ninth round of China-Norway talks on a Free Trade Agreement, the signing of which would have been crucially important for Oslo, ended in failure.

The situation gradually deteriorated, and the diplomatic crisis became endemic. In early January 2012, the Norwegian media even released news that the Foreign Ministry of Norway was going to block the granting of permanent observer status to China in the Arctic Council (which China had been seeking since 2009), if Beijing did not resume constructive dialogue. However, these warnings were not taken seriously, and China continued to take repressive measures: Chinese authorities regularly refused visas to many ranking experts, journalists and politicians (even to former Prime-Minister Kjell Magne Bondevik). Fears were voiced that the restoration of Norway-China relations would take up to a decade.

The business community pressured Norway's government to unfreeze official contact with Beijing. In early January 2012, the Minister of Trade and Industry of Norway, Trond Giske, met with major Norwegian exporter companies. During that meeting, the Managing Director of the Norwegian Shipowners’ Association Sturla Henriksen stated that "…It has become obvious today that Norway needs China more than China needs Norway. This is why the solution should clearly come from the Norwegian side". He also emphasized that it was necessary to act with caution and to carry out a thorough political assessment of the situation.

In early November 2012, at the ASEM Summit in Myanmar, Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg had a meeting with China’s Premier of the State Council Wen Jiabao, where they discussed the state of bilateral relations. This started the process of their gradual normalization, consolidated by the statement of Minister of Foreign Affairs of Norway Espen Barth Eide that Norway would support China’s accession to the Arctic Council.

Rules of the game for newcomers to the Arctic Council

What opportunities will China gain from permanent observer status in the Arctic Council? To answer this question, it is appropriate to look at the organization's regulations, which clearly define the limits of permanent observer capabilities.

First, there is a set of seven criteria that each new observer in the AC must comply with. Among them, the key criteria are the requirements to “recognize the Arctic states’ sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction in the Arctic”, and to “recognize that an extensive legal framework applies to the Arctic Ocean, notably, the Law of the Sea, and that this framework provides a solid foundation for responsible management of this ocean.”

Second, observers are invited to participate directly in the work of the Arctic Council at the level of its subsidiary bodies, but may also be invited to special meetings when necessary, subject to consensus among the eight members of the Organization. At the AC meetings, observers may, at Chair’s discretion, submit written or oral statements on issues under consideration, as well as participate in the discussion.

The abovementioned Rules of Procedure unequivocally ascribe a secondary role to observers in the AC hierarchy and preclude any opportunity for new players to impose their own “rules of the game” in the region. China's recent loud statements call into question its readiness to follow the preset pattern of the AC regulations. One of the statements was made by rear-admiral In Cho, who expressed the view that the Arctic is the common property of the world and no nation alone can claim authority over it. A similar statement was made by Cheng Baozhi, a researcher from the Shanghai Institute for International Studies. According to him, “It is unimaginable that non-Arctic states will remain users of Arctic shipping routes and consumers of Arctic energy without playing a role in the decision-making process, and an end to the Arctic states’ monopoly of Arctic affairs is now imperative".

Later, however, Chinese experts attempted to downplay the established stereotype of the “Chinese threat in the Arctic” as much as they could, and portray the regional ambitions of this country exclusively in positive terms. Thus, one of the leading Chinese experts on the Arctic, Vice-President of the Shanghai Institute of International Studies Professor Yang Jian stated that China “respects the sovereignty and sovereign rights of Arctic countries”, “has no direct interest in the Arctic region and will not use its influence”, but “as a large country, … it has a contribution to make in advancing the causes of peace and security in the region.” Chinese officials began to avoid any comments regarding the Arctic altogether, so as not to give another informational cause to spread negative perceptions.

Having acquired the status of permanent observer in the Arctic Council, China officially reiterated its readiness to comply with the abovementioned principles, which is indirect evidence of the low level of its political ambitions in the Arctic, and at the same time its constructive desire to promote the development of the region. The very fact of being admitted to the AC has, however, a certain political and symbolic significance for Beijing, since it indicates an absence of discrimination and prejudice on the part of the circumpolar powers.

Freedom of maneuver

Another relevant question is what practical benefit China can obtain from its presence in the Arctic Council. In our view, Beijing will not be able to use its new status as leverage to achieve its regional policy priorities, which are focused in the economic domain. This conclusion can be made based on the understanding of the AC's substantive role as a forum that unites all interested players across the Arctic. Besides, some of its members (Canada and the Nordic countries) apply continuous effort to make the decisions of this Organization practically targeted and legally binding. Some progress has been already made toward that goal: in May 2011 the Agreement on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic was signed, and in May 2013 so was the Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic. The unanimity of all AC members will most likely be limited to environmental issues, since in all other areas the interests of the actors quite often do not coincide or even turn out to be diametrically opposite. For example, it is hard to imagine that Russia would abandon the advantages of the current Northern Sea Route (NSR) system in favor of the principle of free navigation in the Arctic, which is supported by the U.S., Denmark, China and other major exporter countries. The issue of definite delimitation of the shelf in the Arctic Ocean will be decided in the specialized UN Commission instead of the AC, and also (possibly) at additional negotiations between Russia, Denmark and Canada. The issues of natural resource production and infrastructure development are also outside the AC's jurisdiction: each Arctic country decides them in its own way. Under these circumstances expansion of the competences of the Arctic Council seems unrealistic.

Thus, Beijing's presence in the Arctic Council may have a purely reputational and symbolic importance for it. Moreover, China expects that in its new capacity it will be able to convey its position to the AC member states, and participate as much as it can in drawing up and implementing the regional agenda. Meanwhile, China’s involvement in specific economic projects in the Arctic (which constitutes the basis of its regional policy) will primarily depend on the development of efficient bilateral partnerships with each circumpolar power separately.

Russia and China's Arctic Agenda

At present, the Arctic partnership between Russia and China is at the very initial stage: no official statements at the government level have been made so far regarding joint activities in the region. However, it is already possible to fairly clearly define the content of Arctic cooperation between the two countries.

The first on the list of priorities is the opening by the Chinese shipping companies of the Northern Sea Route, with the first commercial voyage to be launched already during 2013 summer navigation. The Chinese media have not specified which particular company will perform the Arctic voyage, but there is every reason to believe that it will be COSCO – one of the biggest Chinese freight carriers. It was none other than COSCO that announced its plans in September 2012 to study the economic efficiency of shipping operations between the ports of China and Iceland (and, in the long term, other European countries), using the capacity of the NSR.

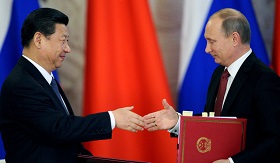

The second priority is the participation of Chinese mining companies in the exploration of the hydrocarbon resources of the Russian Arctic shelf. This issue was discussed during the February 2013 visit to China of the Head of Rosneft, Igor Sechin. The agreements reached took legal form when, within the framework of the talks between Vladimir Putin and the new President of the People’s Republic of China Xi Jinping in Moscow, Rosneft and CNPC agreed on the joint prospecting of the Western Novaya Zemlya offshore area and the South Russian and Medyn-Varandey area in the Pechora Sea.

The other promising areas of Arctic cooperation between Russia and China are the attraction of Chinese investments to the development of infrastructure in the Arctic, exploration and export to the Asia-Pacific markets of hard-to-find extractable ore resources concentrated within the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation, and establishment of environmental tourism centers in the Russian North.

It seems important to extend the principles and dynamics of the Russia-China strategic partnership to the Arctic sooner rather than later, as this will become a new dimension of cooperation between the two countries. Moreover, let us stress once again that all abovementioned areas are within the bilateral competence of Moscow and Beijing. As far as the Arctic Council itself is concerned, Russia took a relaxed stance when the organization expanded its membership through the accession of players from outside the region, including China. Moscow's tacit consent during the vote on this issue vividly demonstrates its positive attitude to the emergence of new actors in Arctic policy. It should be also taken into account that, within the system of Russia’s regional priorities, the Arctic Council is actually assigned a secondary role. This can be proved by the absence of any reference to this organization in the Strategy for Developing the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation and Protecting its National Security for the Period up to the year 2020, approved on February 20, 2013. However, Russia and China can use the Arctic Council as an additional platform for the exchange of views on topical issues of regional development. Nevertheless, the establishment of a Russia-China coalition within the AC seems unrealistic in light of the procedural limitations described above, and potential differences in the perception by the parties of that or other aspects of the Arctic policy.

1. The Norwegian Nobel Prize Committee, which makes the decision on awarding the Nobel Peace Prize, is based in the Norwegian Parliament Building (Storting), but has nothing to do with the activities of the latter.