Timor-Leste's ASEAN Membership: A Malaysian Citizen's Prespective on Integration, Partnership, and Institutional Readiness

In

Log in if you are already registered

Introduction

It has been several months since my last contribution to RIAC, and I must begin with a small apology for the silence. The pause was necessary: I was completing my transition from serving as Chief Executive Officer of two Malaysian foundations to taking up a full-time secondment to the Ministry of Transport and Communications of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste. This new assignment has allowed me to return to a country that has long been close to my heart—and to witness, once again, a moment of profound national transition.

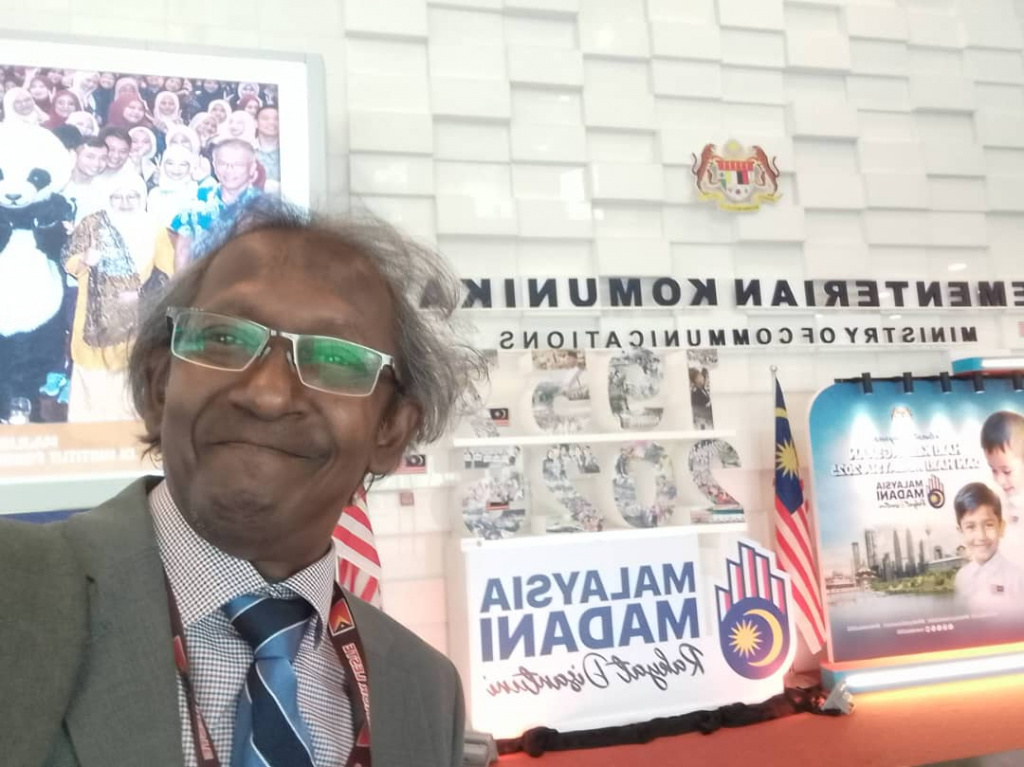

Following my secondment to the Ministry of Transport and Communications (MTC) in early September 2025, I was tasked with advancing inter-ministerial cooperation between Timor-Leste and Malaysia. Within ten days of a high-level internal meeting in late September, I travelled to Kuala Lumpur to deliver an official letter and draft Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) from the Timorese Minister directly to Malaysia’s Minister of Communications.

Flight to Malaysia

At the Ministry of Communications, Malaysia, during bilateral discussions leading to the Timor-Leste–Malaysia Government-to-Government MoU on Communications and Media Cooperation (September 2025).

The mission resulted in a Government-to-Government MoU establishing cooperation in communications, media, and digital development. The agreement was subsequently adopted by the Council of Ministers, underscoring the Government’s commitment to turning international engagement into tangible national policy. This episode illustrates the proactive, results-oriented diplomacy that now underpins Timor-Leste’s preparations for ASEAN membership and its broader partnerships in the region.

Context: Timor-Leste’s Geographic and Development Profile

Timor-Leste is a newly independent nation located in the Asia–Pacific region. The restoration of independence took place on 20 May 2002, marking the end of a long struggle for sovereignty and self-determination. The country is officially known as the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, though it is often referred to internationally as East Timor.

Diagram 1: Map of Timor-Leste.

Diagram 2: Regional Location of Timor-Leste within Southeast Asia

Situated at the cusp of Southeast Asia, Timor-Leste comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, with the western half administered by Indonesia. It also includes the exclave of Oecusse on the island’s north-western coast, and the minor islands of Atauro and Jaco (GOTL, 2023). The nation shares maritime borders with Australia across the Timor Sea and terrestrial boundaries with Indonesia, positioning it strategically between the Indian and Pacific Oceans (see Diagram 1 & 2). Classified by the United Nations as a Least Developed Country (LDC), Timor-Leste covers an area of approximately 14,874 km² (5,743 sq mi). Its capital and largest city is Dili, which also serves as the nation’s political, cultural, and economic centre.

My connection with Timor-Leste stretches back to August 2002, when I first arrived to assist in designing the GKP-World Bank, Government of Malaysia and Switzerland’s support for nation’s early ICT and youth-development programmes. In 2007–2008, I served as International Advisor to the Secretariat of State for Youth and Sports under the Prime Minister’s Office, working to help a young administration shape policies of inclusion and leadership for its new generation. Now, in 2025, I have returned in a new capacity, as Chief International Advisor to support the Minister and Ministry in preparing for one of the most important steps in its modern history: Timor-Leste’s human capital development; resource mobilisation via partnering investment; and formal accession to ASEAN.

This long personal arc has offered me an unusual vantage point. I have seen the country at its birth, during its institutional adolescence, and now as it seeks to enter the regional community of nations. Each stage has brought its own challenges and hopes, but the core question remains unchanged: how can Timor-Leste convert aspiration into capacity?

Now that ASEAN has formally welcomed Timor-Leste as its eleventh member, it will mark the end of a twenty-year aspiration and the beginning of a far more demanding test, the transition from bilateral development dependence to rules-based regional cooperation. As a Malaysian professional working alongside Timorese colleagues within government, I have had the opportunity to observe this moment from inside the system—seeing both the promise of integration and the institutional habits that must change if that promise is to be realised.

Building Institutional Readiness: Lessons from Malaysia’s Administrative Culture

For Timor-Leste, the first real test of ASEAN integration will not be geopolitical but administrative. Membership requires the capacity to plan, implement, and report in line with ASEAN mechanisms, from telecommunications and transport to education and digital-economy cooperation. These are technical, often invisible disciplines that rest on predictable systems, institutional memory, and cross-ministerial communication.

Malaysia’s administrative experience offers instructive parallels. Our early years in ASEAN were not without friction, but the bureaucracy adapted by professionalising its civil service, embedding clear lines of accountability, and prioritising continuity of policy over personality. Even amid political transitions, Malaysia’s ministries have maintained a baseline of competence because of three deliberate choices:

1. Merit and Professionalism. Recruitment and promotion within the Malaysian Administrative and Diplomatic Service were tied to meritocratic evaluation and structured training. Officers were exposed early to international environments, ensuring they understood both national and regional dynamics.

- Institutional Learning. Malaysia invested heavily in civil-service institutes such as INTAN, which trained generations of officers in public-sector management, diplomacy, and ASEAN procedures. This institutionalised learning created a shared vocabulary of governance that transcended individual ministries.

- Inter-Ministerial Coordination. The Prime Minister’s Department and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs worked as integrators across portfolios, preventing policy silos and duplication. Coordination meetings, joint task forces, and regular performance reviews became routine, not exceptions.

For Timor-Leste, replicating such systems need not mean copying Malaysia’s model wholesale, but it must mean establishing predictable routines of professionalism. A small yet critical reform would be the creation of a National Coordination Secretariat for ASEAN Affairs, staffed by technically competent officers from multiple ministries. This body would ensure that every MoU, meeting, or statement aligns with national strategy and ASEAN protocol.

Equally, a Civil Service Training Programme in ASEAN Governance and Diplomacy—perhaps in partnership with Malaysia’s INTAN or Japan’s JICA—would help Timorese officers internalise best practices in negotiation, communication, and procedural management. These are not glamorous reforms, but they are foundational. Nations rise or fall on the strength of their administrative cultures, not merely on the ambitions of their leaders.

Timor-Leste’s young officials are energetic, intelligent, and eager to learn; what they require are institutional guardrails that translate goodwill into predictable outcomes. ASEAN accession can serve as both the pressure and the incentive to install those guardrails quickly. Malaysia, for its part, has an opportunity to share not only technology or infrastructure but also the quiet architecture of competence—the habits that keep states functioning when politics falter.

From Dependency to Partnership: Reframing Cooperation Beyond Aid

Perhaps the most difficult transformation for Timor-Leste in its ASEAN journey is psychological. For more than two decades, the nation’s external relations have been structured around a development-aid paradigm. International cooperation has meant donor funding, technical assistance, and the periodic arrival of projects designed elsewhere. This legacy, understandable in the aftermath of independence, now risks becoming the greatest obstacle to true regional integration.

ASEAN is not a donor consortium. It is a community of peers bound by shared interest and mutual accountability. Unlike the European Union or traditional aid agencies, ASEAN does not transfer funds to member states; it facilitates trade, connectivity, and collective problem-solving. Its success relies on each member’s willingness to contribute expertise and initiative, not on expectations of external grants.

For Timor-Leste, therefore, the question is not what can ASEAN give us? but what can Timor-Leste bring to ASEAN? Every member, regardless of size, earns influence by the value it contributes—ideas, mediation, technical insight, or niche leadership. Singapore offers financial governance; Malaysia, digital policy; Thailand, tourism and agriculture; Indonesia, energy diplomacy. Timor-Leste possesses its own comparative assets: moral credibility from its independence struggle, deep community networks, and a young, linguistically adaptable population. These can be leveraged as soft-power capital through education, youth leadership, and inclusive digital development.

The dependency mindset also distorts how cooperation with external partners is perceived. When officials equate MoUs with funding pipelines, diplomacy becomes transactional opportunism and credibility erodes. Partners quickly recognise when engagement is driven by short-term material expectations rather than shared vision. The result is a cycle of polite meetings, photo opportunities, and unfulfilled agreements, precisely what ASEAN’s cooperative model seeks to overcome.

Moving forward, Timor-Leste should embrace partnership diplomacy, structured around co-investment and shared benefit. In digital transformation, for example, the country could position itself as a pilot state for ASEAN’s inclusive digital-economy agenda—inviting expertise from Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, and ASEAN +3 - China, Japan, and South Korea while offering its own environment as a social-lab for both rural and urban ICT inclusion. This would transform Timor-Leste from aid recipient to innovation partner. In the future partnerships via some ASEAN member nations can also enable collaboration with BRICS nations, while enhancing existing good relations with the EU, USA, Australia, and New Zealand.

Dependency drains dignity; partnership restores it. ASEAN integration gives Timor-Leste the rare opportunity to redefine how it engages the world—not through requests, but through ideas. That is the real measure of sovereignty.

ASEAN Membership as a Test of Governance Maturity and Regional Identity

Timor-Leste’s entry into ASEAN is not merely an act of diplomacy; it is a test of governance maturity. Membership demands the ability to coordinate across ministries, negotiate in good faith, and translate agreements into measurable action. It exposes not only what a state can promise but what its institutions can deliver. The standard of performance will be set by regional peers who measure success through reliability and contribution.

ASEAN integration should be viewed as the country’s most valuable reform instrument. It obliges Timor-Leste to move beyond ad-hoc decision-making and institutionalise discipline—financial, administrative, and diplomatic. Each regional working group, each memorandum of understanding, becomes an audit of capacity. The process itself can catalyse the professionalisation of the public service if managed with sincerity and a learning spirit.

At the same time, ASEAN offers a framework for rediscovering identity. Timor-Leste is geographically and culturally Southeast Asian; joining ASEAN allows it to anchor this identity in shared norms of consensus, mutual respect, and non-interference. For a generation raised between the traumas of conflict and the promises of democracy, ASEAN membership can symbolise a passage from survival politics to constructive regional citizenship.

The measure of this transition will lie in the state’s ability to design and deliver initiatives that demonstrate partnership rather than dependence. Pilot projects that combine local ownership with external technical collaboration—for instance, a digital-inclusion programme co-developed by Timorese institutions and regional partners—can serve as proof that the country is capable of operating within ASEAN’s cooperative economy. Such ventures reveal whether institutions can plan transparently, manage funds responsibly, and share credit fairly. They are small tests with large consequences.

If Timor-Leste succeeds, its accession will strengthen ASEAN’s narrative of inclusivity: that the organisation remains open to any nation prepared to uphold its norms and contribute constructively to its community. Failure, however, would confirm the sceptics who view enlargement as symbolic rather than substantive. The responsibility therefore falls on Timor-Leste’s leaders and civil servants to treat ASEAN membership not as a trophy but as an ongoing examination of credibility.

In the end, the story of ASEAN and Timor-Leste will depend on whether governance can mature faster than resources diminish, and whether partnership can replace dependency before opportunity fades. The choice—and the future—remain in Timor-Leste’s own hands.

Part II of this series will explore how these principles can be tested through specific pilot initiatives linking Timor-Leste with regional and external partners as a practical demonstration of post-aid cooperation and ASEAN readiness.

By Eugene F. Arokiasamy, Chief International Advisor to the Minister, Ministry of Transport and Communications, Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste (seconded from MyProdigy & Women’s Social Foundations of Malaysia to the Ministry of Transport and Communications, Timor-Leste and written in a personal capacity).

Chief International Advisor to the Minister, Ministry of Transport and Communications, Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste

Blog: Eugene Arokiasamy's Blog

Rating: 0