For over five years, Yemen has remained one of the most unstable states on the political map of the Middle East. The Arab Spring exposed the true crisis potential of the country, revealing colossal problems its leadership that had previously been ignored or put on the backburner. Polycracy, separatism, religious animosity, military intervention and reinvigorated terrorist groups – this is still an incomplete list of the problems the Republic of Yemen experiences today.

The Kuwait Dead End

On April 21, 2016, under the auspices of Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed, the United Nations Special Envoy for Yemen, peace talks were opened between the representatives of Yemen’s National Delegation (comprising members of Ansar Allah and the General People’s Congress, GPC) and the Riyadh Group, which is essentially a government in exile controlled by Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi. However, after three-and-a-half months of negotiations, the parties failed to work out a solution for the settlement of the Yemeni crisis.

The Kuwait talks failed largely due to existential reasons: both parties live in parallel worlds, and each world has a right to exist. Yet if Yemen’s National Delegation focused on resolving current differences on the basis of the current distribution of powers, the Riyadh Group, with its retrograde tendencies, appealed to the necessity to restore the status quo of nearly two years ago.

In this case, the stances of both parties are entirely justified. Mansur Hadi and his supporters are trying to adhere to the legal approach, appealing to the need to strictly follow two international regulatory acts that they consider fundamental: the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf’s peace initiative and the UN Security Council Resolution 2216 dated April 14, 2015. Both instruments certainly make the position of the president (who has fled the country) and his government far more advantageous than that of their opponents in the Kuwait talks. For instance, Article 1 of Resolution 2216 requires that the Houthis unilaterally withdraw their troops from the Yemeni capital of Sana’a and from all the areas they have seized, relinquish all “additional arms” and cease all the actions that are “exclusively within the authority of the legitimate Government of Yemen.” It is obvious that implementing even this single article can push Ansar Allah into Yemen’s periphery both geographically and politically.

In turn, the representatives of Yemen’s National Delegation assume the stance of political realism, as it were, basing their position primarily on the balance of power that existed as of the time that the Kuwait talks were taking place. From this point of view, the only decision that could lead to a consensus in resolving the crisis is convening a provisional coalition body: the Presidential Council, which would include members of all the warring parties. Yet should Mansur Hadi agree to this, then, given the fact that he lacks any support “on the ground,” not only would he become a political outsider in Yemen’s new supreme authority (limiting his political career to the authority’s term of office), but he would also lose the possibility to backtrack.

Disappearing Legitimacy

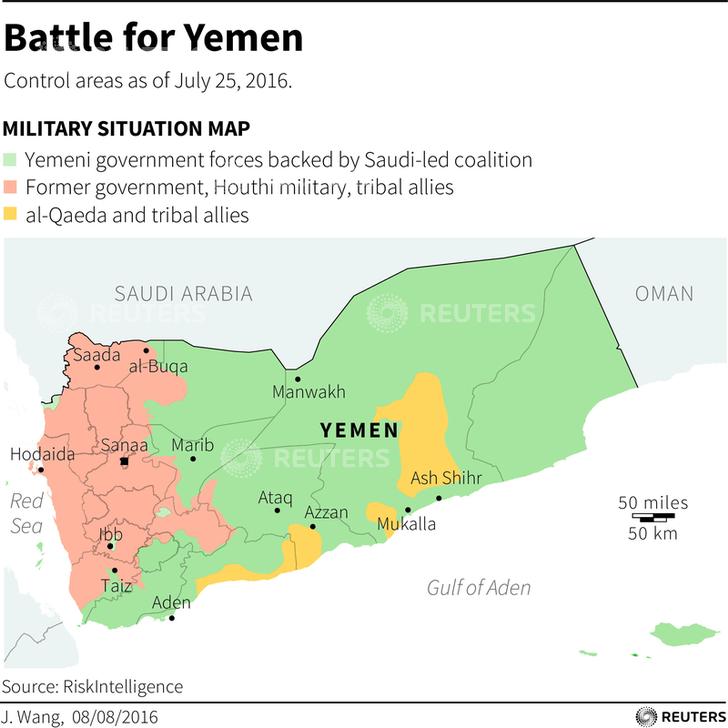

The situation that has been taking shape in Yemen over the past few months plays into the hands of the authorities in Sana’a rather than in Riyadh. This is primarily due to the fact that the military aggression against Yemen by the Saudi-led coalition revealed the Kingdom’s limitations in its ability to resolve the Yemeni conflict to its own benefit. It is not that the military campaign proved to be a zero-sum game for Riyadh; on the contrary, Saudi Arabia managed to achieve its basic goal: it did limit the Houthi expansion into the country.

Saudi Arabia clearly set itself the goal of weakening North Yemen (the Yemen Arab Republic) by supporting the South. South Yemen (the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen) was not as dangerous for Saudis as the North, with which the Kingdom has an unresolved territorial dispute over Najran. Besides, the range of political powers in the South is extremely mixed, unlike in the North, which is dominated by two key political forces: Ansar Allah and the General People’s Congress – and establishing a dialogue with both of them proved not merely difficult, but impossible for the Saudis. Finally, North Yemen has always been characterized by developed tribal structures and weak governmental institutions, unlike South Yemen, where the situation is just the opposite.[i] The tribal consolidation in the North largely explains its military advantage over the South.

A notional “front line” that emerged in the summer of 2015 separating the Houthi–Saleh camp and its opponents virtually followed the former border between the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen and the Yemen Arab Republic, and this “front line” is still relevant.[ii] As the Arab studies expert Sergey Serebrov writes, “The backbone of resistance represented by the Saleh–Houthi alliance in the North and individual al-Hirak factions in the South still staunchly adheres to its national and cultural values, and they consistently fight to mobilize the tribes and the urban population to defend their unique identity.”

Thus a “stagnation” of sorts that has emerged on the Yemeni front makes the continuation of Saudi Arabia’s military campaign less and less viable, especially given the Kingdom’s huge financial expenditures and its record budget deficit of $98 billion in 2015. The most conservative estimate gives the cost of Riyadh’s military campaign at $6.4 billion last year.[iii] Similar figures are given by Adel Bin Muhammad Fakeih, Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Economy and Planning. According to his estimates, $5.3 billion were spent on the operations “Decisive Storm” and “Restoring Hope” in 2015. In practice, this is reflected in the completion of the Emirates’ military mission (they proved to be the coalition’s most combat-ready troops), reduced air strikes by the Royal Saudi Air Force, and the nascent lifting of the blockade of Yemen.[iv] What is more, the International Committee of the Red Cross, Oxfam, Amnesty International and several other NGOs published a series of humanitarian law breaches by the anti-Yemen coalition. Consequently, on February 25, 2016, the European Parliament banned the sale of arms to Saudi Arabia, which put Riyadh and its allies in a very awkward situation.

The current status quo in Yemen – not in the “metaphysical” sense, but the real status quo – that had shaped in the minds of the majority of the global community, is stacked against Mansur Hadi. Time is playing into the hands of the government in Sana’a, and the longer Mansur Hadi remains the country’s nominal president in exile (who does not immediately control the situation in Yemen), the fewer incentives the global community will have to recognize him as the legitimate president. Besides, no one has granted him the status of “permanent” president, and sooner or later, his legitimacy will have run its course, especially given the fact it has long been questioned: Mansur Hadi was elected President in February 2012 by general election for a term of two years; his powers were extended for a year by decision of the House of Representatives, and after that, he became little more than a self-proclaimed president.

New Authorities Doing the Same Old Things

However, right now, appealing to the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf’s peace initiative as the only way to resolve the Yemeni political crisis looks divorced from reality. Firstly, because this mechanism has already shown its impracticability. Mansur Hadi never managed to act as an unbiased “facilitator” of the National Dialogue Conference: the work of at least four of the nine working groups (the Sa’ada Issue Working Group, the Southern Issue Working Group and the State-Building Working Group[v]) has reached an impasse; the new constitution was never adopted; and all the transitional period time limits set by the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf’s peace initiative had long since expired. Secondly, this impracticability is due to the fact that the as-yet unresolved 2016 conflict is substantially different from the one that broke out five years ago during the Arab Spring. In 2011, the main issue on the agenda was a regime change and a peaceful transition of power from Ali Abdullah Saleh to a new head of state, but the recent events have resulted in the conflict assuming religious and ethnic dimensions with a far broader range of political forces involved.

Under these circumstances, and given the failed Kuwait peace talks, the authorities in Sana’a began to search for legal foundations for the functioning of the political institutions they control. As it turned out, they were easy to find: the 1991 Constitution is still in force in Yemen, even though many forgot about it after the events of the Arab Spring. On the basis of the Constitution, the Sana’a authorities convened an extraordinary session of the House of Representatives, which has not held any sessions since the early 2015.

The third convocation of Yemen’s House of Representatives is somewhat unique, as it has been running for more than 13 years (!), since April 2003, when the country held its last parliamentary elections. The elections were postponed several times (in 2009, 2011 and 2014), yet the Parliament continued to work on the basis of Article 64 of the Constitution, which has a provision stating that “elections may not be held in emergency circumstances… until such circumstances cease to exist.” However paradoxical it might sound, the legitimacy of this authority that had “overstayed” its term was the least cause for complaints from the parties to the conflict.

However, Riydh sharply criticized the convening of the House of Representatives in Sana’a on August 13, 2016. The criticism essentially boils down to two points: the legitimacy of convening an extraordinary session, and the quorum. As regards the extraordinary session of the House of Representatives, pursuant to Article 73 of the Constitution, such a session might be convened in three ways: by Presidential decree; upon a written request from at least one third of the total number of deputies; and by decision of the Parliament’s Presidium. Due to objective causes, the first two methods were out of the question, so the Saleh–Houthi alliance used the third option. As of August 13, 2016, the Parliament’s Presidium included four people: Speaker of the House of Representatives of Yemen, Yahya Ali al-Raee, and three deputy speakers – Akram al-Attiyah (from the GPC), Himyar al-Ahmar (son of the late Sheik Abdullah al-Ahmar and representative of the al-Islah party) and the non-aligned Mohammad al-Shaddadi. The by-laws of the House of Representatives state that the Presidium adopts decisions by simple majority, but when it is a two to two split, the decision the speaker voted for passes. Regarding the extraordinary session of the House of Representatives, two of the four members of the Presidium voted in favour: speakers Yahya Ali al-Raee and Akram al-Attiyah, which makes the parliamentary session of August 13 legitimate.

The issue of the quorum prompts even more debates, as Article 71 of the Constitution clearly states that in order for a session of the House of Representatives to be considered legitimate, over half of its members must be present. Since the total number of seats is 301, the quorum requires a minimum of 151 deputies. This is why the presence of 142 deputies at the extraordinary session of the House of Representatives gave Mansur Hadi and his supporters grounds to declare the session illegal. Yet there is an important factor here which drastically alters the situation. The same Article 71 of the Constitution states that the quorum is calculated based on the overall number of deputies “excluding those whose seats were declared vacant.” And here we see that the overall number of deputies dropped from 301 to 275 since 26 deputies had died. Thus, the extraordinary session of Yemen’s parliament was legitimate, both from the point of view of the rules of convening such a session, and from the point of view of calculating the quorum.

The principal decision of the House of Representatives was to convene the Presidential Council, numbering ten people and chaired by Saleh Ali al-Sammad, the Head of Ansar Allah’s political bureau. Kasim Labuzah from the General People’s Congress was appointed deputy chair. In addition to them, Yemen’s new supreme political body included representatives from the Popular Forces Union party, the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party (or simply Ba’ath), the Yemeni Socialist Party and the Nasserist Unionist People’s Organisation.

***

All of this makes the situation in Yemen even more confused and uncertain and essentially reduces any possibility of a compromise should peace talks conducted under the auspices of the UN Special Envoy for Yemen be resumed to naught. The GPC – the Ansar Allah alliance controls North Yemen politically – even with the military intervention – and has achieved significant success in the legal sphere. It was on the initiative of the alliance that another legitimate body, the House of Representatives, resumed its activity in Yemen and legitimately formed another centre of political power.

On the contrary, Mansur Hadi has little to boast about in his exile. His influence in Yemen is measured in fractions of a single percent. The military action of the Saudi-led coalition has become more and more sluggish. And even his reputation as the “only legitimate” figure is now undermined, especially given the Parliament’s supremacy over Mansur Hadi, as it took his powers in 2014. Time is against the president; he has fled his country, which makes his positions in the potential talks more and more vulnerable.

[i] See A.V. Korotaev. Two Socio-Environmental Crises and the Genesis of Tribal Structure in Yemen’s North-East // The Orient (Vostok), 1996 (6).

[ii] Excluding the desert areas of the Ma’rib Governorate and Al-Jouf Region, as well as the traditionally marginal Taiz.

[iii] L.M. Isaev, A.V. Korotaev. Militant Arabia // Asia and Africa Today (Asia i Afrika segodnya), 2016 (8).

[iv] Currently, international air travel is possible to and from Yemen, and al-Hudaydah, the largest port on the Red Sea, is gradually resuming its operations.

[v] See: S.N. Serebrov. Yemen: National Dialogue and the South’s Separatism Problem // Bulletin of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the RAS: Assessments and Ideas (Byulleten’ IV RAN: Otesnki i idei), 2014, vol. 1 (5).