In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, RIAC expert

World War II came to an end almost 70 years ago with around 50 to 80 million people dead, and millions more suffering from the atrocities of that conflict: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity. That war remains to be the bloodiest and the most brutal one in the history of humankind, when the whole world witnessed the unspeakable cruelty – both in the initial aggression and the often disproportionate retaliation. International humanitarian law (IHL), already present at that time, was not enough to protect victims of war and combatants, and WWII highlighted the need to amend the existing international legal regime. Paradoxically, wars, by presenting the impetus for further development of IHL, do not bring only atrocities – they bring a faint hope that future wars would be less inhumane.

World War II came to an end almost 70 years ago with around 50 to 80 million people dead, and millions more suffering from the atrocities of that conflict: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity. That war remains to be the bloodiest and the most brutal one in the history of humankind, when the whole world witnessed the unspeakable cruelty – both in the initial aggression and the often disproportionate retaliation [1]. International humanitarian law (IHL), already present at that time, was not enough to protect victims of war and combatants, and WWII highlighted the need to amend the existing international legal regime. Paradoxically, wars, by presenting the impetus for further development of IHL, do not bring only atrocities – they bring a faint hope that future wars would be less inhumane.

(De)legitimising war

First, IHL does not cover the reasons for war (which is a jus ad bellum issue), but the treatment of its victims, in the most general sense (jus in bello). However, the impact of interwar period and especially the post-WWII agenda brought up a different attitude to wars and hostilities altogether.

War used to be considered as just another (albeit extreme) way of conducting one’s foreign policy, at least until the arguably first international condemnation of war in the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 [2], the precursor of the prohibition of the use of force [3], set out in the UN Charter 17 years after – however, this prohibition is not covered by IHL, it is a matter of general international law (or, to be more specific, jus ad bellum).

Customary IHL rules were present even in the ancient times within various cultures and religions: usually they covered humane treatment of prisoners and general considerations of humanity and mercy.

Customary IHL rules were present even in the ancient times within various cultures and religions [4]: usually they covered humane treatment of prisoners and general considerations of humanity and mercy. The written corpus of international humanitarian law dates back to mid-19th century, with the famous 1864 Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field as its first milestone, with only 10 provisions (compared to today’s hundreds of articles in Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocols). Henry Dunant, a Swiss entrepreneur, humanitarian and a witness of the outrageous 1859 Battle of Solferino [5], is considered to be the initiator for both the Convention and what became the International Committee of Red Cross.

Without getting into historical evolution of IHL before World War II, it is worth noticing that international humanitarian law, or laws of war, consisted of two main branches [6]:

- ‘Law of Geneva’, represented by the Geneva Conventions of 1864, 1905, 1929. The main focus of those Conventions was to protect people hors de combat, no longer able to participate in hostilities (such as wounded and sick).

- ‘Law of the Hague’, named after two Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 (and the Hague Regulations, part of them). This branch covered the conduct of hostilities, occupation – in other words, matters not related directly to victims, but still aimed to protect them (by prohibiting, e.g., means and methods of warfare that bring superfluous suffering).

The law, however, never banished war itself – in the end, humanitarian law tries to be as realistic as possible. However, by introducing some basic rules of warfare, which were present even during WWII, it delegitimised some wars – the most cruel, disproportionate, unlimited in means and methods – while, in fact, legitimising other wars, at least as long as belligerents played by the rules. Question of why is irrelevant in IHL [7], as long as how remains the most important aspect. Today, question of why is governed by international law – the UN Charter prohibition to use force and some customary rules, allowing wars (to be more precise, any use of force) only in 7 circumstances precluding wrongfulness: consent, self-defence, countermeasures, force majeure, distress, necessity and compliance with peremptory norms of international law [8].

Criminalising war

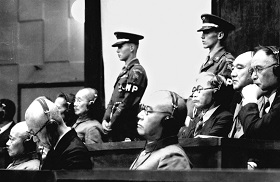

International Military Tribunal in Tokyo

One of the first steps taken by the Allied forces after the end of war was to seek justice and prosecute those responsible for violations of international law and IHL specifically. International Military Tribunals in Nuremberg and Tokyo were not entirely unique: first, because ‘war criminals’ even before WWII were prosecuted (under various charges) by domestic tribunals [9], and second, because there were already some if not full-fledged courts, but international judicial mechanisms – such as the Leipzig War Crimes Trials after WWI [10]. They are unique, however, because they were the first international tribunals to be (mostly) effective in bringing criminals to justice, and for their contribution to international humanitarian and criminal laws.

Under Control Council Law No. 10, the IMT was trying the convicted for four crimes: crimes against peace and wars of aggression, war crimes, crimes against humanity and membership in groups considered to be criminal by the IMT. Interestingly, the crime of genocide was not included into the jurisdiction of the IMT, however the term itself was already coined in 1944 by Raphael Lemkin, who described the Nazi policy of mass murder (speaking mostly about the Holocaust) with this term. Nevertheless, it did not preclude the tribunal to prosecute criminals under other charges for those crimes.

Question of why is irrelevant in IHL, as long as how remains the most important aspect.

There is very little difference to be found between crimes against peace and wars of aggression; later they were coined into one type of crimes against peace [11] (not used now), and then aggression (defined by the UN Generally Assembly Resolution 3314, and hopefully soon-to-be part of the International Criminal Court Statute, starting from 2017). Crimes against peace and wars of aggression are almost self-explanatory today: as stated in the ICC Statute, the crime of aggression is ‘the use of armed force by one State against another State without the justification of self-defence or authorization by the Security Council’ [12]. After World War II, however, the issues of aggression, due to its extremely political meaning, were much more controversial. Here one would easily argue that the criterion for aggression and crimes against peace here is biased by the victor’s justice, and hence the whole IMT might seem unfair. The impartiality of the crime, its political vagueness and semi-centennial Cold War made it impossible to fully codify it up till now.

War crimes constituted violations of laws and customs of war – in other words, violations of IHL. The notion was already present before the creation of the IMT, and Control Council Law No. 10 provided some specifications on what may constitute a war crime [13] – which was later used in the preparations to the 1949 Geneva Conventions.

On 25 May 1993, the UN Security Council

passed resolution 827 formally establishing the

International Criminal Tribunal for the former

Yugoslavia

Crimes against humanity was a relatively new notion: the resembling term was used by Russia, Britain and France in their condemnation of Armenian Genocide as ‘crimes against humanity and civilisation’ [14]. In case of the Nuremberg Tribunal, it was defined as ‘Atrocities and offenses … committed against any civilian population, or persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds whether or not in violation of the domestic laws of the country where perpetrated’ [15]. That notion was extremely new – international human rights law was not yet present, IHL covered mostly the fate of combatants, with less focus on civilian population, but the tribunal could not ignore the atrocities of WWII and had to criminalise it – the crime that covered, among others, Holocaust.

Another interesting issue is the criminalisation of membership in a criminal group. This showed the interesting aspect of international criminal law: if one is a part of a criminal group and able to stop the crime, but assist in committing it, or merely fail to prevent, this person would also be criminally liable. A good example is the Eichmann trial, which took place in 1961 before the Jerusalem District Court: a high-level transportation officer, who ‘simply did his job’ in providing logistics – for mass deportation of Jews to extermination camps – did not kill anyone. However without him, the Holocaust would not be possible (and the argument of another person taking his place’ is inadmissible here). Hannah Arendt described this as ‘banality of evil’ [16], when an ordinary man showed such ‘inability to think’, to realise that he is committing a crime by doing seemingly unrelated job: for him it was not genocide and Holocaust, it was merely transportation issues with trains and people.

International Military Tribunals in Nuremberg and Tokyo were not entirely unique: first, because ‘war criminals’ even before WWII were prosecuted by domestic tribunals, and second, because there were already some if not full-fledged courts, but international judicial mechanisms.

Genocide, as mentioned above, was not included into the IMT jurisprudence. However it soon became an important part of international law with the signing of the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Today, this crime is present most of the statutes of international criminal courts and tribunals, constituting one of the gravest (if not the gravest) international crime.

World War II indisputably created (or at least substantively developed) international criminal law, and post-WWII tribunals showed that violations of international humanitarian law will not remain unpunished. Unfortunately, the Cold War due to political opposition of the two blocks impeded any future trials for other conflicts, unleashing the whole power of international criminal law only in the 1990s with Rwanda and Yugoslavia tribunals. The international humanitarian law, however, did not cease to develop constantly throughout all the 20th century – in the end, even the cold-blooded politicians realised the need to at least try and make wars less inhumane, if not for the people, then at least for having less problems afterwards.

Humanising war

In international humanitarian law the impact of World War II was most evidently seen in the four new Geneva Conventions of 1949, still in power today. Among various novelties in those treaties, it is necessary to pay attention to some of them:

First, it is the inclusion of numerous rules on protection of civilians. The previous Conventions dealt mainly with prisoners of war, sick and wounded, with very limited focus on civilian victims of war: in fact, one of the few provisions somewhat including certain group of civilians was Article 81 of the 1929 Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, and it only covered civilians accompanying armed forces (war correspondents, military support contractors, etc) [17]. In 1949, the Parties decided upon a whole Convention (the last one, number IV), which covered several circumstances concerning protection of civilians:

— General protection included provisions that hospitals cannot be bombed [18], on the obligations to provide access to food, clothing, medical supplies and not to impede humanitarian assistance [19], even special measures for children [20];

— Treatment of protected persons [21], including prohibition of human shields [22], coercion [23], reprisals [24] and hostages [25];

— Protection of non-nationals in the territory of the Party to the conflict [26], as well as provisions covering protected persons in occupied territories [27];

— Other issues on treatment of civilian internees [28], including places of internment [29], food and clothing [30] and many others.

As one might have noticed, the Geneva Convention IV uses the term ‘protected persons’ – unfortunately, covering not all civilians, with the biggest problems arising in cases of own nationals [31]. This still remains to be an issue, extremely complicated in cases of polyethnic societies – such as, for instance, in the former Yugoslavia [32].

If one is a part of a criminal group and able to stop the crime, but assist in committing it, or merely fail to prevent, this person would also be criminally liable.

Another development of the new Geneva Conventions was introduction, although in only one article, common to all four texts, a provision on non-international armed conflicts [33]. This was extremely important and quite new at this time: states decided to at least recognise not only the possibility of such conflicts, but even provide a legal basis for it, albeit very limited in its scope. This was later expanded by 1977 Additional Protocol II to the Geneva Conventions and customary IHL.

1949 Geneva Conventions also started the process of mixing the ‘Hague law’ and the ‘Geneva law’, for instance by complimenting provision in the Hague Regulations [34] and introducing articles applicable to cases of occupation [35]. Interestingly, Common Article 2 included cases of ‘partial or total occupation, … even if the said occupation meets with no armed resistance’ [36]. This was, undoubtedly, included to prevent future possibility of events resembling the 1938 Anschluss of Austria – in other words, all cases of annexation, no matter what status the occupying power may allege to that territory and despite the ‘peacefulness’ of the operation.

Another development of the new Geneva Conventions was introduction, although in only one article, common to all four texts, a provision on non-international armed conflicts.

In addition to the mentioned novelties, 1949 Geneva Conventions codified (inspired by the IMT) some war crimes as ‘grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions’, which included, ‘if committed against persons or property protected by the Convention’, such acts as: ‘wilful killing, torture or inhuman treatment, including biological experiments, wilfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health, and extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly’ [37]. Today the list provided in, for instance, the ICC Statute [38] is much longer, but in 1949 even such limited enumeration of crimes was considered to be rather progressive.

Despite all the developments, it was soon realised (including by the ICRC [39]) that Geneva Conventions cannot fully protect all victims of war (and most of all, civilians), from the effects of hostilities – designating a protective status proved to be not enough. The rules on conduct of hostilities were partly included in the ‘Hague law’, as well as deemed to be of customary nature, but it took a lot of years (and liberation wars of 1960-70s, including the one in Vietnam) to finally come up with 1977 Additional Protocol I, which not only rendered the categorisation of the ‘Hague law’ and the ‘Geneva law’ irrelevant, but provided a thorough legal basis for how the military should conduct its operations.

Despite all the developments, it was soon realised Geneva Conventions cannot fully protect all victims of war, from the effects of hostilities – designating a protective status proved to be not enough.

***

World War II was one of the most dreadful, woeful and appalling event of the 20th century, but it helped the humanity realise the need to prevent such large-scale atrocities which show the darkest corners of human nature. In fact, one can easily find correlation between some significant armed conflicts and the evolution of IHL and international law in general: before WWII, 1907 Convention on War at Sea was signed after the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War, 1929 Geneva Conventions – after World War I, and in post-war period the 1977 Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions were following the decolonisation wars and Vietnam. In the end, one might wonder: does the humanity need wars to be humane?

1. See, e.g., Germany's forgotten victims. The Guardian, 22 October 2003. URL: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/oct/22/worlddispatch.germany" target="_blank" rel="nofollow">http://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/oct/22/worlddispatch.germany

2. The pact was one of the most well-known, but not the only one: 1930-40s were known for various peace and neutrality agreements, which, however, proved to be unrealistic and easily broken. For more information on that, see Karoubi, Mohammad Taghi. Just or Unjust War? International Law and Unilateral Use of Armed Force by States at the Turn of the 20th Century, Ashgate, 2004

3. UN Charter, Article 2 (4)

4. Veuthey, Michael. From Solferino to Kosovo: the Contribution of International Humanitarian Law to International Security, in International Humanitarian law: Origins, New York, Transnational Publishers, Inc., 2003, p. 210-211

5. H. Dunant later wrote a book on his experience, ‘A Memory of Solferino’, where he described, apart from the general hostilities, the way the wounded and sick were not taken care on the battlefield – and how he (and some other people) tried to help them. The book became the literary inspiration for the Convention and the ICRC.

6. Now the distinction is obsolete, the convergence began with 1949 Geneva Conventions and arguably finished with 1977 Additional Protocols. For more information, see: https://www.icrc.org/eng/resources/documents/misc/57jrlq.htm

7. Which strongly contradicts the idea of a ‘just war’, present in world philosophy since, possible, the first war ever fought. Most of the IHL professionals, however, would agree with Harry Patch, one of the last survivors of WWI, who wrote in his 2007 book that ‘War is organised murder, nothing else’. See Patch, Harry. The The Last Fighting Tommy: The Life of Harry Patch, The Oldest Surviving Veteran of the Trenches, Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, 2008

8. As stated, e.g., in the ILC Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, Chapter V, 2005

9. Pritchard, John R. International Humanitarian Intervention and Establishment of an International Jurisdiction Over Crimes Against Humanity: The National and International Military Trials on Crete in 1898, in International Humanitarian law: Origins, New York, Transnational Publishers, Inc., 2003, p. 34

1. For more information, see Mullins, Claude. The Leipzig Trials: An Account of the War Criminals' Trials and Study of German Mentality, London, Witherby, 1921

11. See, e.g., ILC Principles of International Law Recognized in the Charter of the Nürnberg Tribunal and in the Judgement of the Tribunal, Principle VI, 1950

12. ICC Statute, Article 8 bis

13. See Control Council Law No. 10, Art. 2 (1) (b)

14. Interestingly enough, the first suggestion of the Russian Empire by its Foreign Minister, Sergey Sazonov, was to use the term ‘crimes against Christianity and civilisation’, which was later amended for the statement to have less religious and more universal character.

15. See Control Council Law No. 10, Art. 2 (1) (c)

16. See Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Penguin Books, 1963

17. 1929 Geneva Convention, Art. 81

18. Geneva Convention IV, Art. 18

1. Geneva Convention IV, Art. 23

20. Geneva Convention IV, Art. 24

21. With general observations put in Geneva Convention IV, Art. 27

22. Geneva Convention IV, Art. 28

23. Geneva Convention IV, Art. 31

24. Geneva Convention IV, Art. 33

25. Geneva Convention IV, Art. 34

26. Geneva Convention IV, Part III, Section II

27. Geneva Convention IV, Part III, Section III

28. Geneva Convention IV, Part III, Section IV

29. Geneva Convention IV, Part III, Section IV Chapter II

30. Geneva Convention IV, Part III, Section IV, Chapter III

31. Geneva Convention IV, Art. 4

32. In this case ICTY devised a new criteria of allegiance that in some cases replaced nationality and brought large groups of civilians into the ‘protection persons’ category

33. Geneva Convention I-IV, Art. 3

34. 1907 Hague Regulations, Section III

35. Geneva Convention I-IV, Art. 2; Geneva Convention IV, Part III, Section III

36. Geneva Convention I-IV, Art. 2

37. As defined, e.g. In Geneva Convention I, Art. 50; other Conventions use the same provisions under different articles.

38. ICC Statute, Art. 8

39. Draft Rules for the Limitation of the Dangers Incurred by the Civilian Population in Time of War, 2d ed., ICRC, p. 251

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |