Is the Eastern Mediterranean a New Competitor for Russia on the European Gas Markets?

An Israeli gas platform, controlled by

a U.S.-Israeli energy group, is seen in the

Mediterranean sea

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

Expert at the Institute of the Middle East, graduate of International Institute of Energy Policy and Diplomacy at MGIMO

Over the course of less than ten years, large reserves of gas were discovered in Eastern Mediterranean countries (Israel, Cyprus and Egypt), and some say this gas could soon be exported to Europe. When can such exports be organized? In what quantities? And how? And will the Levantine “blue fuel” not challenge Russia’s positions on the European market?

Over the course of less than ten years, large reserves of gas were discovered in Eastern Mediterranean countries (Israel, Cyprus and Egypt), and some say this gas could soon be exported to Europe. When can such exports be organized? In what quantities? And how? And will the Levantine “blue fuel” not challenge Russia’s positions on the European market?

How Much Could the Mediterranean Countries Offer?

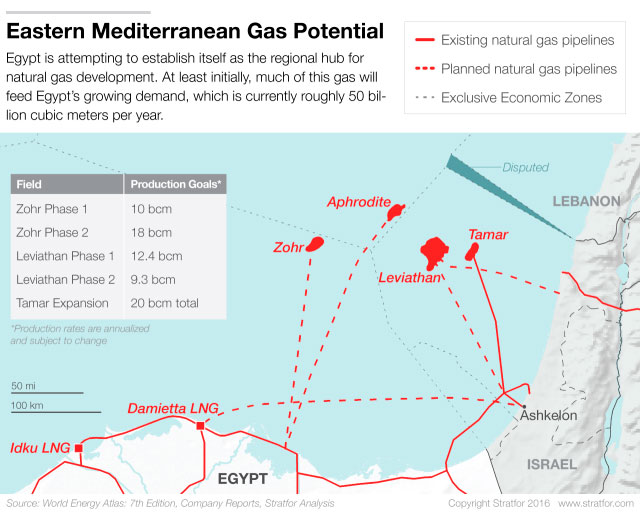

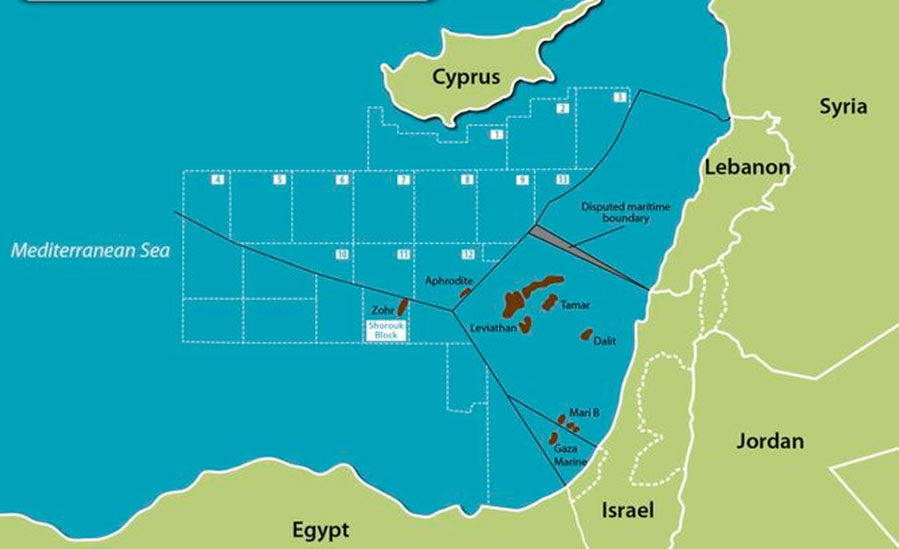

The Mediterranean region drew a lot of attention in 2009, when the Israelis discovered the Tamar gas field with proven reserves of 280 billion cubic metres. A year later, the larger Leviathan gas field, with reserves of 620 billion cubic metres, was discovered. Then the Aphrodite gas field was discovered in Cyprus’ Exclusive Economic Zone, boasting 120 billion cubic metres of gas. The next country to strike it lucky was Egypt, which surprised the world with the discovery of the Zohr gas field, with reserves of 850 billion cubic metres of gas.

Exploration of the Eastern Mediterranean shelf is just picking up pace, and the world’s largest players are involved.

Thus, the countries that have reserves sufficient for the commercial export of natural gas are Egypt (with over 2.7 trillion cubic metres [1]), Israel (about 1 trillion cubic metres) and Cyprus (120 billion cubic metres). Together, the countries of the Levantine basin have a minimum of 3.8 trillion cubic metres of natural gas. This is about eight times less than the reserves of Russia and Qatar and five times less than those of Turkmenistan. Its reserves are comparable to those of Iraq and several times greater than those of Azerbaijan and Norway. It should be noted that, with such reserves, exporting gas to Europe and other relatively distant countries will be profitable should the Levantine countries export their gas jointly.

Figure 1. The Borders of the Levant Basin (from eia.com)

Exploration of the Eastern Mediterranean shelf is just picking up pace, and the world’s largest players are involved. In Israel and Cyprus, the United States’ Noble Energy and Israel’s Delek Group have the strongest positions, with controlling interests in the Leviathan, Tamar, and Aphrodite gas fields. It was the monopoly of these two companies that out a brake on Israel adopting its gas sector development plan. Until recently, the larger parts of the Israeli and Cypriot territories remained unexplored; however, such work is being done now, and it will be expanded. For instance, Cyprus opened its third licensing round in July 2016: foreign investors are invited to participate in exploring three offshore blocks.

BP, Eni, Total and other industry leaders produce hydrocarbons in Egypt. In July 2015, the Egyptian government announced that exploration and follow-up exploration of hydrocarbons were now its priorities.

Only 2D and 3D exploration has been carried out in Lebanon, although no drilling has been done. It should be noted that in 2013, when the Lebanese side planned to hold a licensing tender, such giants as Total, ExonnMobil, Eni, Shell, Statoil, Chevron and Rosneft passed pre-qualification, despite the existing territorial dispute between Lebanon and Israel and the overall tense political situation in the region. Few doubt that there are shelf gas reserves, yet there is no point in expecting gas to start flowing to the markets in the medium term: even if the country’s government finds a way out of the political impasse, it will take no fewer than seven years to hold tenders, carry out exploration work and start production. Therefore, we will not talk about Lebanon in this article.

Without a doubt, Europe will become an attractive market for the Levantine countries, and they will export gas there.

The gas sector has developed to different levels in Cyprus, Israel and Egypt. In Cyprus, natural gas is not produced or even used. Israel has more experience: production has been going on several small fields for many years, and, since 2013, on the Tamar project as well, which covers Israel’s entire demand for natural gas (a little over 8 billion cubic metres per year). Nevertheless, the development of the sector is being slowed down by bureaucratic delays. The long-awaited programme of gas field development was only adopted in June 2016, green-lighting production at the Leviathan field. International experts believe the project will be implemented slowly. The export and production infrastructure in these countries is still to be built up, and that means a further increase in the price of the already expensive shelf gas.

Egypt is in a peculiar situation: starting in 2014, the country turned from a net exporter of gas into a net importer. It got to the point when the plants built for exporting liquefied natural gas (LNG) turned out to be “redundant,” and the country had to lease a terminal to import the fuel. The gas deficit on the domestic market in 2015 was estimated at 5–7 billion cubic metres annually, and by 2018, it is expected to grow to 10 billion cubic metres.

Building the infrastructure to liquefy gas is attractive because it will ensure Israel’s gas access to markets far beyond Europe.

Let us emphasize that the issue of consumption is important to estimate the quantities of gas the countries of the Levant basin are ready to sell. The crux of the matter is that Egypt and Israel have a rapidly growing demand for gas: demand in Egypt has grown by 50 per cent over the past ten years, with demand in Israel increasing fourfold. Experts are not forecasting a significant drop in the consumption rate in either country [2]. This means reduced quantities of gas available for export.

Only company statements and plans allow to give estimates of the amounts of “blue fuel” will be produced in Israel, Cyprus and Egypt in the next five years. Production on the largest fields will have started by 2019–2020. According to the estimates given by the government and the production companies (which are a priori positive), production should grow by 12.4 billion cubic metres in Israel and by 20 billion cubic metres in Egypt by 2020, with production in Cyprus set to reach 8.3 billion cubic metres in the same timeframe. If we subtract the approximate amounts of additional consumption (13.7 billion cubic metres annually [3]), we get about 27 billion cubic metres of hydrocarbons available for export annually. To compare, in 2015, Russia’s Gazprom exported almost 160 billion cubic metres to Europe. Even if all of the Eastern Mediterranean gas went to Europe in the coming five years, its share in the European gas import would be below 8 per cent.

Figure.2. Large Gas Fields in the Levant Basin

Is Europe an Attractive Market for Gas? Or Are there Other Markets?

Europe will increase its gas consumption over the next few years. Experts from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies predict that demand for imported gas growing by 88 billion annually by 2030. The main reason for this will be the use of natural gas as buffer fuel while the transition to the use of sustainable energy is made. The demand is predicted to drop after 2035. This is why (especially given the European Union’s continuing policy of diversifying its imports) the European market will be attractive for Israel, Cyprus and Egypt.

However, not by Europe alone. Gas demand among the Eastern Mediterranean’s Middle Eastern neighbours has grown at a faster pace in recent years. The bare facts also show that it is the neighbouring countries that will receive the first shipments of hydrocarbons: Israel intends to sign its first export agreements with Jordan, Egypt (the agreement was not cancelled after the discovery of the Zohr field), Palestine and local companies.

Without a doubt, Europe will become an attractive market for the Levantine countries, and they will export gas there. However, to organize exports, an expensive infrastructure needs to be built. And before that, the most convenient routes need to be found, and this is by no means an easy task.

Table 1. Total reserves of natural gas in Israel, Cyprus and Egypt and the largest fields discovered since 2009. Source: EIA, BP, Eni, Noble Energy, Delek Group

Country (total proven reserves*) | Field | Discovered (year) | Proven reserves (billions of cubic metres) | Production start (year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Israel (1 trillion cubic metres) | Tamar | 2009 | 280 | 2013 |

| Leviathan | 2010 | 580–620 | late 2019** | |

| Cyprus (120–200 billion cubic metres) | Aphrodite | 2011 | 120–200 | 2020** |

| Egypt (2.7 trillion cubic metres) | Zohr | 2015 | 850 | 2018** |

| West Nile Delta concessions fields | 2010–2015 | 142 | 2017** | |

| Atoll | 2018** | 42 | 2018** | |

* ВР’s estimate of proven reserves + companies’ latest data on new fields.

** According to the latest information from the production companies.

What Routes and At What Price?

As of August 2016, the Eastern Mediterranean countries have not yet decided on their priority export models. However, the future plan is probably already shaping up: in late August, Cyprus and Egypt signed a framework agreement on constructing a gas pipeline to transport gas from Cyprus’ Aphrodite gas field to Egypt. This route will be used to transport gas to Egypt’s domestic market; re-export is possible, but in relatively small quantities (without Israel participating in the plan).

The project is at the initial stages and does not include all the players, so let us consider other possible routes discussed by governments and international experts: 1) the construction of an Israel – Cyprus – Greece pipeline; 2) the construction of an LNG plant in Israel or the use of Egypt’s LNG infrastructure by Israel and Cyprus; 3) the Eastern Mediterranean countries joining the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) project that is being implemented to transport Azerbaijani gas via Turkey; 4) transit pipeline export via Turkey.

As regards the potential transit of Levantine gas, Turkish diplomacy has both “entry point” and “exit point” problems: for various reasons, its relations with both producer and consumer countries have been strained.

In terms of the political risks and the prospects of getting contracts signed quickly, the first two options appear to be the most promising: either a pipeline from Israel and Cyprus, or LNG. In April 2016, the European Commission allocated 2 million euros for an economic assessment of the first route. Building the infrastructure to liquefy gas is attractive because it will ensure Israel’s gas access to markets far beyond Europe. It could be necessary, should new gas reserves be discovered in the region. Previously, constructing an LNG terminal appeared to be too expensive, and building pipelines to tap into the Egyptian gas appeared too risky, given the difficult economic situation in the region. What is more, experts predict that the LNG market will become oversaturated soon, and that is an argument against the LNG project.

Connection to the Southern Gas Corridor appears logical only when we take into account the fact that Azerbaijan is unable to fill the pipeline to capacity all by itself. There have been reports over the past year of several countries wishing to connect to the Southern Gas Corridor. There has been talk about it in Egypt, Cyprus, Israel, Iraq, Iran and Turkmenistan. Yet, in May 2016, the Minister of Energy of Azerbaijan said that Azerbaijan had received no serious proposals from these countries on joining the project.

Experts note that, from a purely economic point of view, the least expensive option is transit through Turkey (without connecting to the SGC) [4]. The arguments against this option will be discussed below.

Today, it is difficult to predict the prices of Eastern Mediterranean gas, as it is not yet known what the production costs will be, what kind of infrastructure will be built and, most importantly, what the situation on the European gas market will look like by the time these questions have been resolved.

The Turkish Question

The geographical location of Turkey gives it excellent chances to become an energy hub for the transit of Middle Eastern, Central Asian and Russian hydrocarbons to Europe. Yet the Middle East would not have been the Middle East as we know it had it not been for the twists and turns of its ethnic and religious politics, which often hold economic considerations hostage. In this respect, Turkey is no different from other countries in the region, especially if Recep Erdogan stays in power. As regards the potential transit of Levantine gas, Turkish diplomacy has both “entry point” and “exit point” problems: for various reasons, its relations with both producer and consumer countries have been strained.

Turkey cannot boast that it has high-quality cooperative ties with Cyprus, Israel or Egypt. Its relations with Nicosia are at a low point due to the Cyprus question. It is telling that Turkey did not participate in the recent summits of the heads of state of the Eastern Mediterranean, where energy was the primary subject of discussion: the meetings were held between the Republic of Cyprus, Egypt and Greece and the Republic of Cyprus, Israel and Greece. Incidentally, on July 22, 2016, information appeared that the Cypriot authorities had revoked permission to construct a pipeline from Israel to Turkey.

Active cooperation between Turkey and Israel had virtually stopped after the incident with the Turkish Gaza Freedom Flotilla in 2010, when Israel’s military raided a Turkish ship as it attempted to breach the blockade of Gaza. The issues were resolved in June 2016. However, it appears unlikely that relations between the two countries will return to the level there were at before the incident. Under these circumstances, expensive infrastructure projects cannot be implemented.

As for Egypt, the Turkish authorities still do not recognize the legitimacy of the Abdel Fattah el-Sisi government that replaced the Muslim Brotherhood, which Ankara supported. Both Cairo and Tel Aviv are annoyed by Turkey’s loyalty to the pro-Iranian Hamas organization. One would hope that for the sake of economic benefit, Egypt, Turkey and Israel would make concessions on these issues. But the Muslim Brotherhood is also supported by Qatar, and Egypt depends on generous aid from Saudi Arabia. In view of the ongoing covert war over influence in the region, relations within this polygon are highly unlikely to improve in the near future.

Turkey’s recent politics make it a less desirable partner for gas importers as well. The European Commission has already approved one Turkish transit project, the Southern Gas Corridor. This expensive infrastructure ($45 billion) will ensure the supply of 10 billion cubic metres of gas annually. It is highly doubtful that the European side will want to receive more of their gas via Turkey. Ankara’s unpredictable foreign and domestic policies seriously undermine Turkey’s image. After the attempted coup in June 2016 and the events that followed, the prospects for improving Turkey’s image are minimal at best. It is obvious that Turkey’s breakthroughs in relations with Russia and Israel in June 2016 bear testimony to the fact that the country’s leadership understands the need to improve relations with its neighbours. Yet these neighbours will now have a different approach to appraising the risks and, consequently, the profitability of Turkish projects in the near future.

However, as far as the long term prospects are concerned, the Turkish route should not be ruled out entirely. In addition to purely economic profitability and geographic expediency, until recently, support from the United States had been another argument in Turkey’s favour. The United States actively lobbies the idea of buttressing Eastern Mediterranean cooperation based on economic (or, rather, gas-related) interests. And they continue to stubbornly include Turkey in the region, as they clearly hope to use this approach to resolve certain political issues.

So What Should We Expect?

At the moment, there are too many variables to single out specific possible developments in the Levant equation: the reserves are only now being explored, the technical and economic assessment has not yet been carried out on any of the transportation routes, and the gas market itself is being transformed as it becomes more global and more tied to the oil market.

Let us outline the three possible general scenarios for the next 5–10 years. The negative scenario entails: exporting Israeli gas to the neighbouring countries; continued growth of consumption in Egypt, which would delay the transition to exporting gas; the absence of new fields in the region; and the delay of construction of the pipeline to Europe due to its low profitability or the impossibility of reaching an agreement on the conditions of the countries’ participation.

The positive scenario entails the countries, including Lebanon, discovering new gas reserves, which will make the construction of powerful export infrastructure profitable. The countries will export jointly. Some experts note that Egypt could play a special role by acting as an “energy hub” between the Eastern Mediterranean and Europe.

The third scenario appears to be the most probable. By 2018, Israel will have started exporting gas to neighbouring countries. In a few years (depending on the consumption growth), Egypt will become a net exporter of gas. By that time, new information on reserves will have been received; perhaps Lebanon will start exploration activities. Should new fields be discovered, a unified regional infrastructure for exporting gas to the European may be built. Cyprus and Israel should definitely be expected to cooperate; Egypt may, too, as Egypt and Cyprus signed a framework agreement in late August.

At the moment, there are too many variables to single out specific possible developments in the Levant equation: the reserves are only now being explored, the technical and economic assessment has not yet been carried out on any of the transportation routes, and the gas market itself is being transformed as it becomes more global and more tied to the oil market.

We shall also exclude the scenario of the accelerated construction of a pipeline via Turkey, or of connecting the Eastern Mediterranean to the Southern Gas Corridor. This is unlikely due to a whole series of obstacles that are, in one way or another, related to Turkish politics.

Thus, using the data available, we can state that in the next five to seven years, Levantine gas will have little appreciable influence on Russia’s positions on the European market. However, further down the line, Israel, Cyprus, Egypt and Lebanon could become large gas exporters.

However, they have a long way to go: Egypt will have to limit its consumption of energy resources; Cyprus will have to build a national gas industry from scratch; Israel will have to stop creating obstacles for its emerging industry; and Lebanon should, for starters, elect a president and speed up the work of its fragmented government. The situation on the gas market will certainly have changed by that time, and it is quite possible that Russia will be more concerned with other competitors that already influence (such as Qatar), or could influence in the future (such as the United States), the drop in gas prices on the European gas market.

1. Data from BP Statistical Review of World Energy June 2016, including estimated reserves of the Zohr field unaccounted for in the BP statistics.

2. Nikos Tsafos Egypt: A Market for Natural Gas from Cyprus and Israel? // The German Marshall Fund of the United States. 2015, p. 3.

3. This figure includes the estimated consumption growth: 3.3 billion cubic metres annually in Egypt; and 11.9 billion cubic metres annually in Israel. The growth rate for Israel is calculated based on the assumption that average annual consumption growth in the coming years will be about 7 per cent a year.

4. Hydrocarbon Developments in the Eastern Mediterranean: The Case for Pragmatism / Atlantic Council, Global Energy Center and Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center, p. 2.

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |