The Water Must Flow

Koksaray Water Reservoir, Uzbekistan

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

MA, Higher School of Economics and blogger

While rich in water resources, Central Asia suffers from their uneven distribution. Issues of water management, use and sufficiency contribute to a broad range of problems which rarely lead to constructive cooperation among regional leaders. Much more often, their discussion only increases mutual aversion. Joint water consumption begets rivalry between countries, creating a major source of regional tensions along with territorial disputes and extremism.

While rich in water resources, Central Asia suffers from their uneven distribution. Issues of water management, use and sufficiency contribute to a broad range of problems which rarely lead to constructive cooperation among regional leaders. Much more often, their discussion only increases mutual aversion. Joint water consumption begets rivalry between countries, creating a major source of regional tensions along with territorial disputes and extremism.

He Who Controls Water Controls Central Asia?

In speaking of the Central Asian water problem, one should start by defining it, as well as the parties involved. The problem stems from lopsided distribution, combined with ineffective utilization and the dependence of the population on agriculture, and consequently on irrigation.

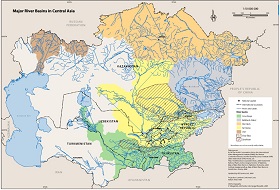

Central Asia has a lot of water in the basins of the rivers Amu Darya, Syr Darya, Chui and Talas, Ob'-Irtysh and Zarafshan, and of Lake Balkhash (see Fig. 1. Basins of Major Rivers in Central Asia).

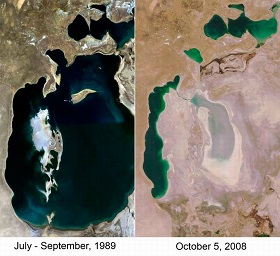

Most of the disputes centre around the Amu Darya and Syr Darya river basins, which form the basin of the Aral Sea which all Central Asian states to have pledged to maintain and protect. Water is a matter of concern for the entire region, specifically Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, as it is they who exploit the waters of Amu Darya and Syr Darya, both transboundary rivers. The key role belongs to Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Although Turkmenistan's dependence on Amu Darya is enormous since one-third of its water goes into the gigantic Turkmenbashi Canal (the long straight line along the Iran border in Fig. 1), Ashkhabad normally stays away from public discussion, mostly due to its isolationism and non-participation in the regional competition for leadership. Turkmenistan prefers to solve the water problem on its own through digging storage reservoirs and improvement of the irrigation system. Although dependent on the Syr Darya basin, Kazakhstan also stays apart, as in many other regional issues. Its water policy includes restoration of water resources, which makes Astana look much more civilized than its neighbors.

Amu Darya and Syr Darya originate in the mountains and are fed by glaciers. Thus, the key water pools, reservoirs and hydropower plants belong to Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, the upstream countries that can regulate the flow for all the rest. The system of reservoirs and canals built in the Soviet period relied on cooperation between the republics, as Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan stored water in wintertime in order to send it to the irrigation canals of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan in summer. As a result, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan could not use the water for power generation in winter, and the downstream countries supplied them with energy in exchange. The scheme is still operating, but growing hydrocarbon prices limit the upstream states' desire to purchase power, rather than using the water for their own energy production.

For Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, where winters are cold, electric power is a matter of survival for their populations. Meanwhile, their intent to use water for power generation makes the downstream countries wary of possible water shortages in the reservoirs.

Most of the disputes centre around the Amu

Darya and Syr Darya river basins, which form

the basin of the Aral Sea

One way or another, the problem of water boils down to its availability, which depends on such factors as glacier reserves, mountain precipitation, flow regulation by the upstream countries, and irrigation and drainage systems, each of them quite delicate. Anxious about possible region-wide shortages, the downstream countries, primarily Uzbekistan, have built about 50 reservoirs.

No matter how strange it may seem, a crisis is more likely due to climate change, and not because Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan take too much water for power generation. Glaciers feeding Amu Darya and other rivers are melting, which indicates river water increases in medium term and an abrupt drop later. Among Central Asian leaders, Uzbek President Islam Karimov seems to be most keen on long-term planning. Hence, Tashkent's concern about access to water is quite predictable. At the same time, Uzbekistan is taking no steps to improve the situation, even such simple and obvious ones as upgrading its irrigation and drainage network, raising its efficiency and cutting water losses. The same applies to Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, which do not prioritize restoration and modernization of their irrigation systems. From time to time, experts and the media mention Tajikistan's interest in drip irrigation. capable of raising efficiency of water use in agriculture. but for the time being such projects are being executed only by private companies with no government participation.

Megaprojects

While the region's water conundrum is eternal, it has been acquiring new features, with its current aggravation directly related to the revival of two megaprojects, namely the Rogun and Kambaratin hydropower stations.

Planned for the river Naryn, which joins Kara Darya to form Syr Darya, the 1,900-MW Kambaratin plant is to be the most powerful station in Kyrgyzstan, allowing it to become an electricity exporter. The Rogun scheme on the Vakhsh River is even more ambitious, since Tajikistan intends to build a 3,600-MW plant with an annual output of 13.1 billion kWh. Were it to reach its planned capacity, the Rogun plant could become the 29th largest hydropower plant in the world. However, neither upstream country has enough funds for their ventures.

Interest in the Rogun and Kambaratin plants has been growing due to both the scale of the projects and the growing protests of Uzbekistan. Mr. Karimov has qualified the project as "stupid" and even announced the possibility of a regional water war, focusing the world community's attention on the problems of large hydropower plants, and more generally on Central Asian water resources. Experts are expecting a repeat assessment of the Rogun project by the World Bank, although it is not exactly clear in whose interests the work is being done. Various workshops and think tanks in Washington keep wondering why the World Bank is assessing the facility's design safety but not the practical need for its construction in the first place.

It's obvious that Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan do not need such megaprojects to meet their energy requirements. Several small plants would easily suffice. Their intentions to export power do not appeal to the downstream countries, which are concerned about loss of profits from their own sales of energy resources. The Rogun and Kambaratin stations in and of themselves pose a somewhat illusionary threat to the water supply of the lower reaches of Amu Darya and Syr Darya. Both projects envisage power plants higher upstream than the existing major reservoirs, since these stations cannot ensure water supply all year round. Hence the threat to the downstream countries is economic rather than ecological.

Uzbekistan, the projects' strongest opponent, has several reasons for concern. Firstly, a water shortage is sure to affect the poorest section of the population, which feels a significant impact from even the slightest flow fluctuations. Secondly, the Uzbek economy is based on cotton, which involves practically the entire population, especially in the harvest period. No water means no cotton. The extractive approach to national economy, i.e. extraction of resources for sale with no concern for their depletion, as well as its agricultural basis, are the factors which largely define overall governance. Should these foundations shift, the government's concerns over its own position may appear all too legitimate.

Regulation of Water Consumption

Formally, water consumption is controlled by the Central Asian Interstate Commission for Water Coordination established in 1992. The Commission established the Amu Darya and Syr Darya basin-wide water management corporations. The Commission is intended to enforce water consumption quotas and the protection of water resources, whereas the corporations are in charge of water supply, as prescribed by quotas defined by representatives of Central Asian states at the Commission's sessions. The Commission is fairly active, and effective in managing the use of transboundary water flows. However, this is either unknown or intentionally neglected during analyses of the water problem, as many think that formal institutions in Central Asia are invalid and should not be accounted for. Some experts in Washington suggest setting up a regional organization to help handle the water problem. In fact, the logic is rather questionable - if formal institutions are failing to resolve the problem, then simply creating another one will accomplish nothing.

Utilization of the transboundary river resources is a regional problem, with its significance fully acnowledged by the countries of Central Asia. This is why a joint search for a solution, with no interference from international bodies, should not only alleviate the issue, but also set an example for successful tackling of other common problems, and thus in turn improve the region's image. This is particularly true in terms of the ecological side of the matter, as the economic side, i.e. the construction of large hydropower plants, still lacks a regulation mechanism beyond bilateral meetings between representatives of rival states.

Russia and the Central Asian Water Problem

Since Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are eager to develop their economies on the basis of water resources, Russia can actively participate in their projects. The hydrocarbon shale boom obviously threatens Russia's position in the energy market, and might well drive Russian businesses to alternative energy production, i.e. hydropower plants. Russia has already made some steps through participation in the Kambaratin project. The Rogun plant seems less attractive both due to its conflict potential and to high costs.

At the same time, there are also opportunities outside large-scale ventures. As seen from research on the impact of climate change on Central Asian water resources, the glaciers are melting. In the long term, the process risks resulting in regional instability due to water shortage for a growing population. Since Russia perceives Central Asia as its sphere of influence, or the "Russian Underbelly", according to some creative Western authors, regional stability should be a key task for Moscow's foreign policy. No major power would like to share borders with a region immersed in fighting not merely for water but for survival. Therefore it appears reasonable for Russia to take part in researching Central Asian climate change and green energy production. At the same time, Russia's engagement in restoring the Aral Sea or modernizing the irrigation system is unlikely to be worthwhile. Outright financing of such projects is doomed to failure, while Moscow still lacks the experience needed to create specialized regional programs or finance directly involved communities in Central Asia.

Russia is a key regional actor moderating relations between Central Asian states. One example of its success in this respect is the lowering of tensions around the construction of the Kambaratin power plant through inviting Uzbekistan to discuss its concerns, and promising fresh design expertise. Moscow has shown the Central Asian states that their voices are being heard and regarded as significant, which has improved the situation both around the Kambaratin and throughout the region.

The region's water problem may as well become aggravated in the future, so internal and external actors should seek qualitative analyses and forecasts based on investigation of water resource prospects, threats to agriculture, and alternative energy opportunities, since the two as yet non-existent power plants are not likely to solve the energy shortage issue, especially in the long term. It must be emphasized that the collapse of agriculture is the greatest threat, since it is would affect all population groups, driving them to fight for survival and generating an explosive hotbed of volatility and extremism. Whoever offered the resources they needed to survive would come to control the region. Anyone interested in Central Asian stability has to understand that the water must flow.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |