The New Role of Migration in Russia’s Demographic Development

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Doctor of Economics, Director of the Center for Human Demography and Ecology, RAS Institute of Economic Forecasting

Migration is a socio-demographic process that has been socially, economically, politically and culturally critical throughout the history of mankind. Migration has invariably remained one of the three fundamental mechanisms that, with reproduction, form population size and age structure, while also maintaining the demographic balance within certain territorial entities at diverse levels – from small rural settlements to megalopolises, countries and even continents.

Migration and Demography

1

Migration is a socio-demographic process that has been socially, economically, politically and culturally critical throughout the history of mankind. Migration has invariably remained one of the three fundamental mechanisms that, with reproduction, form population size and age structure, while also maintaining the demographic balance within certain territorial entities at diverse levels – from small rural settlements to megalopolises, countries and even continents.

In the 20th century, industrialization and urbanization turned Russia into an arena for massive internal migration. Domestic migration flows have taken place in Russia before, but this article is devoted to external migration flows, that have always been less significant for the country.

During certain historical periods Russia used immigrants to replenish its population. In the 18th century, rapid territorial expansion caused “depletion of colonization resources: Russians and Little Russians” and the government “resorted to foreign settlers.” It was then that the Germans arrived in the Volga Region, attracted by Catherine II’s overture to foreign colonists. Later, Germans, Serbs, Bulgarians, Greeks, Armenians and the Gagauz took part in the development of this New Russia and were integrated into the Russian population. There have also been upticks in emigration, for example during the 1917 Revolution and the ensuing Civil War. But Russia’s population has, on the whole, not been dependant on external migration flows.

In the Soviet period, Russia, as a constituent part of the USSR, saw centrifugal rather than centripetal migration flows. Russia’s residents were scattered through other Soviet republics, which did not have an impact on Russia’s population growth. Statistics for more recent periods suggest that in 1955-1975 natural population growth went arm in arm with, and numerically exceeded, migration losses. This situation only changed in the mid-1970s, when migration out of the republics exceeded the inflow into the republics, tipping the migration balance into Russia's favor. From 1975, the population was growing both through the birth rate and as a result of the influx from other Soviet republics. However, in those days nobody linked these processes to international migration flows. A fairly isolated country, the USSR barely participated in them, while migration between individual republics were regarded as domestic.

The disintegration of the USSR changed the situation, affecting the assessment of Russia’s place in the international migration system and creating the myth about Russia being the second largest destination for migrants after the United States. This myth is based on the erratic interpretation of publications of the UN Population Division. Researchers tended to neglect the fact that the UN assessments referred to people of migrant stock, i.e. the total number of people residing in a country other than the country of their birth. Since the 2002 census revealed 12 million natives of other states resident in Russia, UN experts qualified them as international migrants, while also mentioning that, as far as the USSR was concerned, the bulk were internal migrants who became international only due to the emergence of new borders.

The disintegration of the USSR changed the situation, affecting the assessment of Russia’s place in the international migration system and creating the myth about Russia being the second largest destination for migrants after the United States.

Most migrants arrived during the Soviet period. According to the UN, in 1990 they numbered 11.5 million, matching the USSR-wide census of 1989. The census detailed the Soviet Union’s ethnic composition: more than 50 percent ethnic Russians, rising to 89 percent including Russified Ukrainians and Belarusians. The top ten identities also included Armenians, Jews, Tatars, Chechens, Kazakhs, Ossetians and Ingush, with other national or ethnic groups comprising just 1.5 percent. According to the 2002 census, a total of 12 million Russian residents were born outside its territory, prompting new UN assessments. Against 1990, this growth was insignificant, with the same proportion taken by former USSR citizens born outside Russia, in a former Soviet republic, that belong to Russia’s core ethnic and national groups. The group includes children from the Soviet pioneer settlers of the “virgin lands” who were born in Kazakhstan, children of members of the armed forces serving in different USSR republics, Chechens, the Ingush and representatives of other nationalities born after deportation in Kazakhstan, Central Asia and other places. At the same time, people of migrant stock would not include those who were born in Russia but lived outside the country (as servicemen, appointed specialists, etc.), later returning to Russia to be defined as migrants. In fact, the 12 million migrants mentioned in the UN reviews and subsequent World Bank documents cited by Russian authors appears too high a figure. In comparing countries by the total number of people born abroad, one should use relative, rather than absolute, figures. In terms of the total migrant population (factoring in the reservations outlined above), Russia is definitely ahead of all European countries, but taking population size into account its place in Europe is fairly modest (see Table 1).

Table 1. Share of persons born abroad in population of European countries, 2008

| Country | Share, % | Country | Share, % | Country | Share, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luxemburg | 32,2 | Germany | 11,6 | Italy | 7,3 |

| Austria | 17,2 | Greece | 11,6 | Malta | 6,7 |

| Estonia | 16,4 | France | 11,0 | Lithuania | 6,6 |

| Latvia | 15,6 | Great Britain | 11,0 | Finland | 4,0 |

| Ireland | 14,1 | The Netherlands | 10,9 | Czech Republic | 3,7 |

| Sweden | 13,8 | Norway | 10,2 | Poland | 2,7 |

| Spain | 13,8 | Denmark | 8,8 | Slovakia | 0,9 |

| Slovenia | 12,0 | Russia | 8,5 | Romania | 0,8 |

| Iceland | 11,8 | Portugal | 7,4 |

Source: Migrants in Europe. A statistical portrait of the first and second generations. Eurostat, 2011. Tablе 1.1. Р. 25.

Naturally, apart from registered migrants, Russia hosts numerous undocumented (illegal) immigrants who are likely to affect the economic and social environment, the labor market, etc. However, genuine demographic importance can only be attached to those immigrants that settle in Russia, boosting the population and taking citizenship, not those that temporarily swell the ranks of those in the labor market (legally and illegally).

As has been noted, although since the mid-1970s Russia’s migration balance with former Soviet republics has been positive, and immigration has become a permanent addition to natural population growth, until 1990 it actually accounted for less than a quarter of the natural increase. It is not surprising that, in those days, no one regarded immigration as a significant source of Russia’s population growth. Admittedly, this does not mean that the potential role that migration could play had been completely misunderstood. Natural population decline in the Russian Federation had been predicted long ago, while plans were excitedly discussed for boosting Russia's diminishing demographics through migration from regions where the labor-market was overpopulated. In those days these plans remained on paper, because the labor-deficient territories, i.e. Central Russia and Siberia, were not ready to receive settlers, while Central Asia was not yet prepared to cede its residents.

The migration of the 1990s, and to a great extent the 2000s, was mainly on a return basis, involving a significant volume of cases of repatriation, as can be seen from the migrants' ethnic composition recorded until 2007.

However, soon the role of migration changed: first, to make a greater contribution to population growth; and then in 1992, when natural growth was replaced by natural loss, migration became the only avenue to boost the population. Even higher migration volumes after the collapse of the USSR could not make up for these heavy natural losses.

Of course, the compensating role of migration should not be underestimated. Having peaked at 148.6 million in 1993, Russia's population had lost 5.5 million by early 2011, with the natural loss standing at 13.2 million. In other words, migration was able to compensate for this loss to the tune of 7.7 million people, or 58 percent.

At the same time, it is essential to comprehend the largely unique nature of migration over the two past decades.

First, note the uneven distribution of migration over the period in question – 4.9 million (72 percent) out of the 6.8-million migratory increment in 1990-2010 came in the years 1990-2000, while the registered annual growth later plummeted.

Besides, the migration of the 1990s, and to a great extent the 2000s, was mainly on a return basis, involving a significant volume of cases of repatriation, as can be seen from the migrants' ethnic composition recorded until 2007. In the 1990s-2000s, migrants into Russia were mostly Russian expatriates and their descendants, while this situation began to visibly change in the mid to late 2000s (see Table 2).

Table 2. Share of the Russian Federation ethnicities in the migratory increment, %

| Year | Russia's national and ethnic groups | Including Russians | Year | Russia's national and ethnic groups | Including Russians |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 133,2 | 112,2 | 1998 | 69,8 | 60,8 |

| 1992 | 116,6 | 101,3 | 1999 | 67,3 | 57,2 |

| 1993 | 86,1 | 75,7 | 2000 | 66,8 | 58,2 |

| 1994 | 75,4 | 67,0 | 2001 | 89,0 | 76,5 |

| 1995 | 72,6 | 63,4 | 2002 | 77,8 | 66,8 |

| 1996 | 68,5 | 60,0 | 2003 | 83,7 | 67,3 |

| 1997 | 69,8 | 61,6 | 2004 | 83,2 | 72,9 |

| 1998 | 69,8 | 60,8 | 2005 | 62,8 | 56,1 |

| 1999 | 67,3 | 57,2 | 2006 | 50,2 | 42,8 |

| 2000 | 66,8 | 58,2 | 2007 | 36,8 | 30,3 |

Sources: Demographic Yearbook of Russia 1996. Moscow,1996. Table 7.8; Demographic Yearbook of Russia 2001. Moscow, 2001. Table 7.9; Demographic Yearbook of Russia 2008. Moscow, 2008. Table 7.11

It was at about this time that the Russian authorities began to worry, and attempted to attract compatriots back to Russia, in an effort to preserve the repatriation trend, and in 2006 initiated the State Program on Assistance to Voluntary Resettlement of Compatriots to Russia. However, the program was not an unmitigated success, apparently because by that time the mobile resources of return migration had largely been exhausted. Whereas the program envisaged welcoming 200,000 people in 2007-2009, slightly over 16,000 returned.

The contraction of the natural resource-base has been felt for quite a long time and can be seen in diminishing migration flows. Today, pure migration into Russia is relatively low compared to other European countries.

This testifies to the abrupt constriction of the traditional, in a sense natural Russian resource-base that had generated the migratory increment and, consequently, a considerable compensation for the natural population loss in the first post-Soviet decade. It does not mean that Russia will be deprived of the new migrants, but it is likely to be much more difficult to keep this migration increment high, since the new-generation migrants in Russia will have to close a much wider cultural gap.

The contraction of the natural resource-base has been felt for quite a long time and can be seen in diminishing migration flows. Today, pure migration into Russia is relatively low compared to other European countries (see Table 3), despite the recent artificial measures taken to boost migration.

Table 3. Pure migration to Russia and certain European countries in 2008, per 1,000 of the population

| Country | Per 1,000 of the population | Country | Per 1,000 of the population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Switzerland | 12,7 | Finland | 2,9 |

| Spain | 10,0 | Hungary | 2,8 |

| Norway | 9,4 | Great Britain | 2,6 |

| Slovenia | 9,1 | Slovakia | 2,4 |

| Italy | 7,6 | Russia | 1,8 |

| Sweden | 6,0 | France | 1,2 |

| Belgium | 5,9 | Portugal | 0,9 |

| Malta | 5,9 | Ireland | 0,8 |

| Czech Republic | 5,4 | Bulgaria | -0,1 |

| Austria | 4,7 | Estonia | -0,5 |

| Cyprus | 4,5 | Germany | -0,7 |

| Iceland | 3,6 | Poland | -0,7 |

| Denmark | 3,4 | Latvia | -1,1 |

| The Netherlands | 3,2 | Lithuania | -2,3 |

Source: URL: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tps00177&plugin=1

Until 2007, migration statistics had included people coming from abroad who obtain their first permanent residence registration, making them part of Russia's permanently resident population. In 2007, the statistical category of migrants was expanded to embrace first-time temporary residence permit holders. As a result, the pure migration figure rose to 258,000 (against 155,000 in 2006) considerably improving Russia's demographic balance by reducing natural loss by approximately 100,000. However, classifying foreigners who have temporary residency in Russia as part of its population seems questionable. In the years 2007-2009, pure migration figures remained stable at about 260,000, but in 2010 they dropped virtually to the 2006 level. In 2011, the migration calculation rules were amended once again. According to the Federal Statistics Service (FSS) website, "following international recommendations, since 2011, statistical listing of long-term migration shall also include persons registered at their place of residence for a period of nine months and more." Calculated this way, the migration increment in 2011 reached 320,000, overtaking natural population loss. Nevertheless, this statistical strategy only accentuates the issue of whether Russia really is doing better or whether it is basking in comfortable illusions. The sense of urgency seems to be masked by favorable changes in the natural loss parameters, which are falling, and thus may be balanced out by the relatively minor migration increment. But this cannot continue forever, as Russia's natural population growth does not have entirely positive prospects.

Natural population loss in Russia is not accidental; rather it originates from the population reproduction pattern with low birth and mortality rates present in Russia since the 1960s.

Although the natural increase collapsed only in the late 1980s, its occurrence was no surprise. Soviet forecasts predicted natural loss in early 21st century but it happened 10 years earlier than anticipated, i.e. in the early 1990s, both due to the socio-economic crisis and excessively optimistic Soviet estimates. In any case, natural population loss in Russia is not accidental; rather it originates from the population reproduction pattern with low birth and mortality rates present in Russia since the 1960s. For a time natural growth remained relatively high, mainly due to the population age structure that had accumulated considerable demographic increase potential. Once this resource was exhausted, the birth-mortality balance in Russia collapsed, resulting in a phenomenon known as the to Russia cross, when the birth and mortality curves intersect, deaths exceed births, and natural growth is replaced by natural loss.

Natural growth (loss) in the population hinges on three factors: birthrate, death rate and age structure. Whereas these first two can, to some extent, be amended by policies (although this is also quite complicated), the third factor is virtually unalterable. Russia's current age structure is rigid, and to a great extent predetermined, and cannot be significantly altered in coming decades.

Since Russia's current age composition was formed in a volatile time, the age pyramid is considerably distorted. Consequently, the dynamics of various gender and age elements is irregular and undulating, with alternating demographically and socio-economically rising and falling waves.

Russia had failed to return to the early 1990s population levels, nor is it likely to in the foreseeable future.

In the 2000s, despite the continued population loss, the gender and age changes were in a growth phase to provide the country with a kind of demographic dividend or bonus. As a matter of fact, this period saw two demographically beneficial concurrent shifts.

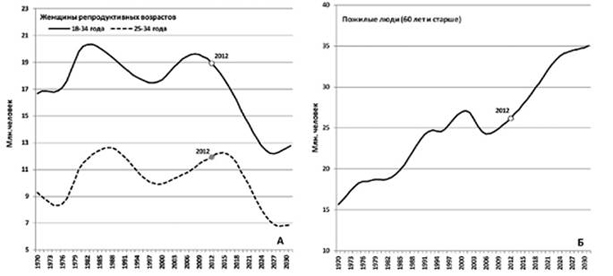

The first was due to an increase in the number of births in the 1980s that explains the increased number of women of reproductive age in the 1990s. The number of women aged 15 to 50 increased from 36.3 million in 1992 to 40 million in 2002-2003, after which fell slightly but remained relatively high compared to previous levels. In 1999-2009, the 18-35 subgroup, which sees most births, grew by more than two million, which could not but contribute to the birth rate after 1999. Currently, growth of this female group has tailed out, while the FSS expects a huge drop – by 4.7 million to 2020 and by more than seven million by 2025. The trends for women aged 25-34 appears better, as this group is becoming more important as later births are becoming more common. However, this group is also set to contract in size, even though, due to a delay in the falling birth rate, this group is still showing growth (see Fig. 1A).

The second change comes from the fact that since 2001, the scanty 1941-1945 generations were crossing the 60-years-of-age mark. As a result, in 2001-2006, the number of people aged 60 and over fell by 10 percent, decelerating the mortality rate because most deaths occur in the older sections of the population. Now that this period has come to an end, the number of senior citizens and their share in the population will grow fast to reach levels unprecedented for Russia (see Fig. 1B). Deaths will also rise, even if the intensity of age-related mortality falls, which appears unlikely. But even if this drop takes place, it should cover the groups of the oldest sections of the population.

Figure 1. The number of women aged 18-34 and 25-34 and seniors – actual and the FSS average forecast, 1970–2030

Source: . Demographic Forecast 2030. URL: http://www.gks.ru/wps/wcm/connect/rosstat_main/rosstat/ru/statistics/population/demography/index.html#

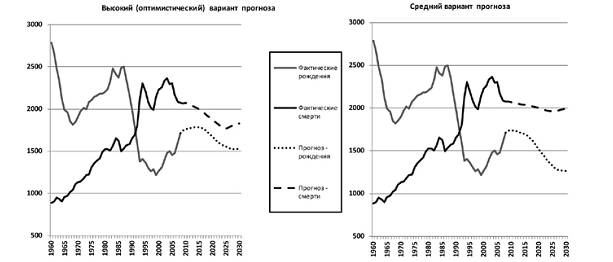

With the number of births falling and the number of deaths rising, the figures will move further apart, increasing the seemingly narrowed gap in the Russian cross (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2. The number of births and deaths in Russia – actual in 1960-2010 and the FSS high-case and medium-case forecasts, in thousand

Source: Demographic Yearbook of Russia 2009. Moscow, 2009. Table 8.5

Today, this gap is closing; with natural population loss swiftly diminishing largely due to the Russian age pyramid’s particular structure, generating an impression that natural population growth will recover. The dynamics are frequently interpreted as a demographic policy success and a stable positive trend that will soon draw a line under negative growth, see zero levels restored and, possibly, deliver positive dynamics. In fact, this scenario seems unlikely, as all predictions indicate a repeat wave of natural loss in the near future. Natural loss will accelerate even within the FSS’s most optimistic scenario. Since optimistic scenarios rarely transpire, the moderate scenario seems most likely, with natural loss at over 500,000 a year in first years of the next decade, with that figure set to grow.

2

While all types of migration are important, visibly influencing the economic, social and labor environment, it is the immigration segment that settles in the country to boost its permanent population that is of primary demographic significance. The volume of this kind of migration mainly depends on a nation’s demographic policies, i.e. the extent to which a decrease is viewed as permissible, and the desirability of stabilization or growth. These guidelines should be developed within a process of dialog between the authorities and society and involve a societal consensus that does not seem easily obtainable.

Appeals to understand the new role of migration in Russia's demographics appeared in research literature in the mid-1990s. "[Russia] has left the development stage of a country with high natural growth and significant emigration, whereas immigration appears to be the main if not the only source for the population growth." "We are looking at a turning point in Russia's demographic development. Similar to many other industrialized countries, in the foreseeable future, Russia is not likely to be able to rely on maintaining or growing its demographic potential through natural increase, with migration becoming the key factor in demographic dynamics […] In order to ensure population loss is a short-term phenomenon and ensure the population in the middle of the first decade of the 21st century is above the 1990 level with the further potential to rise, the realistically optimistic scenarios of birth and mortality rates should be combined with intensive pure migration at approximately half a million a year […] For Russia's current development stage, this level should be seen as […] highly desirable given its overall demographic dynamics."

Unfortunately, developments have taken a different direction, with society shot-through with resilient anti-immigrant sentiments that contradict the country’s real-life demographic needs.

High annual volumes of pure migration have not been attained, and by the end of the first decade of the 21st century, Russia had failed to return to the early 1990s population levels, nor is it likely to in the foreseeable future. The outcome is predictable; however the Population of Russia reports cited above refrained from making predictions, opting rather to present analytical forecasts indicating possible trajectories of Russia's demographic development under various scenarios of demographic change. At the same time, these papers invariably underlined the limited opportunity for large-scale migration to Russia. "The reception of immigrants in large numbers, especially foreign-language speakers with other cultural traditions is a process that is far from painless, while the problems will only double due to Russia's current economic and social climate." "Russia cannot but sense the objective limits of its migration capacity. Similar to other countries, these limits hinge on the labor market, and in particular on the throughput of the adaptation and assimilation mechanisms, as well as on the speed of the immigrants' adaptation and socio-cultural integration." "We should avoid extreme conclusions and hopes for unrealistically high levels of population influx from other places, as the near future will see neither the economic nor the political or even cultural preconditions for this process. The current priority should be to assist with the resettlement inflow of Russians and other Russian speakers from the former USSR, as well as members of Russia's indigenous peoples (Tatars, Bashkirs, etc.) who found themselves outside Russia’s borders but who are willing to return."

The approach taken seems to have been to refrain from boosting immigration and instead using return migration mechanisms in the initial 10-15 years after the Soviet Union collapsed. The aim was to expand the capacity to absorb immigration inflows, thus ensuring this “compensating immigration” continues to grow in the future, when demographic and economic conditions make this growth inevitable.

Unfortunately, developments have taken a different direction, with society shot-through with resilient anti-immigrant sentiments that contradict the country’s real-life demographic needs.

The academic community needed time to comprehend the new role of migration as a significant means of boosting Russia's population. Back in 2001, the above forecast for migration volumes needed to balance-out the population loss was criticized along the lines that it "testifies less to the authors’ major methodological miscalculations and more to their neglect of the possibility of overcome depopulation through natural population movement and the unfounded overestimation of the capabilities and virtues of a demographic development pattern based on complete dependence on external migration." The authors insisted on forecasts that "knowingly reject possible transition to migratory dependence."

This inflated impression of the scale of this immigration, its ethnic composition and threats are deep-rooted in Russians’ minds and present a major psychological barrier to the recognition of immigration's new role as the country’s most significant demographic resource.

Obsolete approaches to migration also formed the basis of official forecasts by the FSS. As was noted back in the early 2000s, "FSS official forecasts are also based on the need keep the migratory increment low, while none of their scenarios suggest a changing trend to higher migration. Possibly, the absence of these alternatives is where the FSS predictions are most vulnerable. We criticized this approach in a report several years ago, but the FSS would neither consider our analysis nor change their attitudes to forecasting migration."

However, the greatest misunderstanding regarding the new reality found reflection in public and political debate. Anti-immigrant sentiments have been on the rise, often stirred up by officials who publicly overstate the number of immigrants in the country, especially illegal migrants, to distort the ethnic composition landscape and intimidate the population with an exaggerated migration threat.

In 2005, targeted research was carried out to analyze the scope of this exaggerated popular perception of the volume and threat posed by migration in seven constituent entities of the Russian Federation. These perceptions were compared with the regional data on the presence of different nationalities associated with migration contained in the 2002 census. The survey showed that "on the average, the respondents were inclined to exaggerate FSS data by an order of two (192 times)", in different regions and toward different ethnic groups. At the same time, across the board "the respondents replied unanimously that over 10 years, the proportion of these groups would rise 1.5-1.8 times. This was an opinion held irrespective of the region surveyed; the group assessed; or even the perception of the group prevalent among the population of the region surveyed."

This inflated impression of the scale of this immigration, its ethnic composition and threats are deep-rooted in Russians’ minds and present a major psychological barrier to the recognition of immigration's new role as the country’s most significant demographic resource. This is echoed in the disorientating statements made by key Russian politicians. For example in 2007, Sergey Mironov, the then Chairman of the Federation Council, said that "solving Russia's demographic problems with help of migrants is a dead-end." "We must handle demographic problems ourselves through a higher birthrate and lower mortality rate." According to the RBK News Agency, Mr. Mironov maintained that, if demographic problems are resolved by incomers from other countries in the future as well, in historical terms "it will no longer be Russia."

The current Concept envisages the population stabilizing at 142-143 million by 2016 and rising to 145 million by 2025, in part due to compensatory migration.

the new Concept (strategic policy document) to

develop and outline the goal.

Gradually and somewhat belatedly, the demographic inevitability of this migratory resource was becoming a reality and found reflection in academic literature, official statements and demographic forecasting.

A publication in the mid-2000s noted that "in any case, natural loss will cause population decline", but "at least during the coming 20 years… a balanced migration policy that meets Russia's national interests could make the migratory component a means to compensate for this natural loss," whereas "the migratory increment above natural loss" should ensure a demographic increase. "In order to maintain the population at 143-144 million, we should have a migratory increment of 490,000 in 2006-2025. Under this scenario the migratory increment would cover the natural loss (expected to be about 9.8 million for those years), while the population size would remain stable, in line with the strategic goal of Russia's demographic development."

Migration’s new demographic role has also been increasingly recognized in official documents. Approved by the Government in September 2001, the Concept for Demographic Development of Russia through 2015 established a migration priority of "regulating migration flows to create efficient mechanisms to compensate for natural population loss in the Russian Federation." In October 2007, Russia's President approved the new Concept (strategic policy document) to develop and outline the goal. The current Concept envisages the population stabilizing at 142-143 million by 2016 and rising to 145 million by 2025, in part due to compensatory migration. Therefore, the annual migratory increment should be at least 200,000 through 2016, and in excess of 300,000 in subsequent years.

Consequently, the FSS has also changed its approach to the migratory increment within its demographic forecasting. In the late 1990s, official demographic predictions were definitely to "tacitly imply the inherited ideal of migratory isolation." The latest FSS forecast envisaged plummeting net migration into Russia by 2010: an approximately four-fold drop against the 1996 level under one scenario, and almost 10-fold drop under the other scenario. A decade later the situation had changed.

Developed taking the Concept for Demographic Policy of the Russian Federation through 2025 into account, the 2009 FSS forecast envisages average annual pure migration in 2030 at the same level as in 1996 under the medium-case scenario, 40 percent lower than the 1996 level under the lowest scenario, and 1.5 times higher than the 1996 level under the highest scenario.

We believe that this approach is more justified than the attitude expressed by UN experts, who in their latest forecast (2010) determined the pure migration volume for Russia at 2.7 million in 2010-2030, i.e. 1.8 million less than the FSS minimal forecast – which is based on the most optimistic scenario for birth and mortality rates. The FSS medium case is based on total migration through 2030 at 7.2 million. Consequently, the UN’s medium scenario envisions Russia's population at 136.4 million by 2030, i.e. 2.6 million less than given in the medium case outlined by the FSS.

Thus, Russia is increasingly recognizing the immutable fact that, in the foreseeable future, migration will inevitably be employed as partial or full compensation for natural population loss (probably excess compensation if population growth becomes a priority), or as an addition to positive natural growth. That raises the question: what are the probable dimensions of this migratory increment?

3

The answer to this question depends on numerous factors and conditions, which are difficult to discuss within the purely demographic analysis set out in this article. We can offer some considerations related to the likely evolution of natural population growth in Russia, since its dimensions provide the platform for the development of a national migratory strategy.

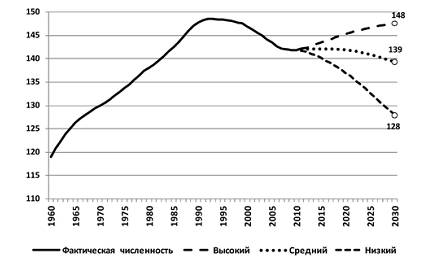

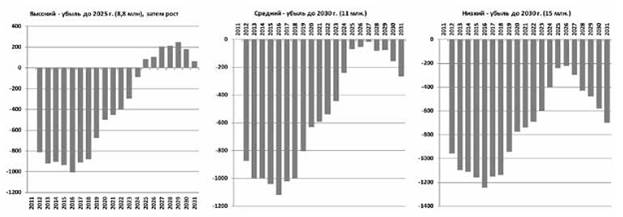

Figure 3. Variation in Russian population size – actual and within three FSS scenarios through 2030, in millions

Source: Demographic Yearbook of Russia 2009. Moscow, 2009. Tables 8.1, 8.2

Proceeding from the desirability of at least halting Russia’s population decline, during the entire period in question, migration volume should be maintained at levels that compensate for natural loss. According to the FSS forecast, by 2030, natural loss could reach 5.0-19.5 million depending on the birthrate and mortality dynamics, while predicted pure migration during the same period amounts to 4.5-11 million.

Demographics is not the only factor that lends a new meaning to the mass influx of migrants into Russia. The economy is no less important, and therefore understanding how they are interconnected is essential.

Hence, alongside scenarios that envisage using migration to fully compensate for natural loss, possibly in excess, that would stabilize and even under certain conditions deliver population growth, there also are likely scenarios in which any such compensation is impossible, which would mean a continued downward trend in Russia's population (see Fig. 3).

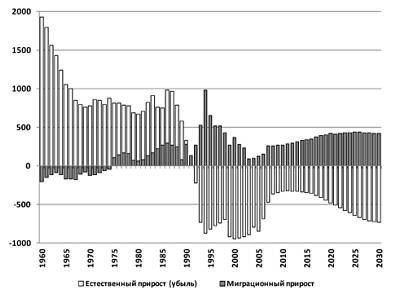

Figure 4 outlines the components of Russia's population growth – actual through 2010 and expected under the medium-case scenario that is normally regarded as most likely.

Figure 4. Components of Russian population increase (decrease) – actual for the period 1960-2010 and under the FSS medium case forecast through 2030, in thousand population

Sources: Demographic Yearbook of Russia 1993: A Statistical Collection // FSS of Russia. Moscow, 1994. P. 10; Demographic Yearbook of Russia 2010. P. 26; Socio-Economic Status of Russia 2010. January-November. P. 292, 294. Estimated Population Size of Russia until 2030 (A Statistical Bulletin). Moscow, 2010

The diagram clearly depicts the critical point after which natural growth gives way to natural loss, while the only positive contribution to population size is derived from pure migration. This forecast also shows the migratory increment compensating only partially for natural population loss through 2030, which would result in a population drop. Under the medium-case scenario, the average annual migratory increment is likely to stand at approximately 400,000, while if it is to compensate for the forecasted natural population loss (slightly over 10 million in 20 years), the migratory increment should amount to approximately 500,000 each year. This figure is approximate but, as we have already seen, quite stable. And achieving population growth would require even higher levels.

Demographics is not the only factor that lends a new meaning to the mass influx of migrants into Russia. The economy is no less important, and therefore understanding how they are interconnected is essential.

We have witnessed how the robust migrant influx to Russia over the past 20 years has contributed greatly to the alleviation of the country’s demographic problems and how it had its roots in the whirlwind repatriation processes that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. However, this case seems rather exceptional, since global migration trends are predominantly labor-oriented and streamlined by economic factors. Massive international labor migration originates from the difference in the labor market potentials between the country of origin and the destination country, while the demographic consequences, obviously significant, are merely a side-effect. As a rule, immigrants cannot be attracted in sufficient numbers in the absence of an economic mechanism, even if there is a clear and pressing demographic need.

Moreover, demographic considerations are speculative. They are not uniformly perceived at any one time by everybody, which makes them less than viable for implementation in a proactive migration policy. At the same time, economic considerations are pinpointed and involve numerous economic agents, that doggedly push through even concerted resistance from opponents of immigration and emigration.

In the long run, demographic and economic factors, although different in nature, become interlocked. In fact, using migration as an approach to solving the demographic problems faced by countries suffering from depopulation, or heading in that direction, to a great extent becomes reality due to the immutable laws of economics.

Economic requirements may differ in gravity and be in discord with the demographic situation, as can clearly be seen from the dynamics of the "demographic dividend" seen in Russia during the past two decades.

Although Russia has been experiencing consistent population decline since 1992, changes in the balance of different age groups have been beneficial economically, socially and demographically to alleviate or conceal the acuteness of the worsening crisis.

In reality, this population decline had been long accompanied by growing numbers and rising share of people who are classified as “employable” (i.e. men aged from 16 to 60 and women aged from 16 to 55) – from under 84 million in 1993 to over 90 million in 2006. At the same time, the number of children under the age of 16 fell, from 35.8 million in 1992 to 22.7 million in 2006. The number of old-age pensioners remained almost stable at 29-30 million, and was in fact slightly lower in 2006 than in 2002. As a result, the demographic burden on the employable population was continuously decreasing. In 1993, there were 771 dependants (under and above the employable age) per 1,000 people who are classed as “employable,” while in 2006 this was at an almost unprecedented low of 580 per 1,000. Of course, this had a beneficial impact on the state's social spending, albeit a minimal one as far as demographic relationships are concerned. Note that the situation on the labor market was far from ideal, as demand exceeded supply – and was met by legal and illegal labor migration.

Figure 5. Loss of employable population along three FSS scenarios until 2030, thousand population

Source: Demographic Yearbook of Russia 2009. Moscow, 2009. Table 8.4

In the mid-2000s, the situation deteriorated. In 2007, the employable population plummeted for the first time in a lengthy period. The gap is snowballing against a backdrop of continued natural population decline in Russia, as all the available forecasts show. Even under the optimistic scenario, over the period 2012-2022 the employable group is set to lose almost eight million people, and is not likely to start to show even slight growth before 2025. Should demographic processes get worse, in 2022 this drop may reach 9.6-11 million with no growth anticipated to follow (see Fig. 5).

In the coming 10-15 years, the forceful compression of the labor market seems inevitable, accompanied by a growing economic burden on the employable group. Currently, the employable 1,000 matches 570 children and seniors, while the lowest scenario predicts a growth of 159, the medium scenario – 213, and the highest – 242 dependants. The rise should involve skyrocketing social spending, further aggravating the economic situation in the country.

Thus, demographics should drive mounting demands for immigrant labor within the economy. Eventually, the labor market or economy in a broad sense should become the key pro-immigration lobby, more powerful than politicians. Demographics and the economy will require growing numbers of immigrants, while this escalating necessity will amplify the external migratory pressure from less developed or affluent countries suffering from overpopulation, guaranteeing a permanent influx of settlers from adjacent and possibly distant countries. Migration-related issues will become unavoidable, topping Russia's agenda in the 21st century. This is clearly a major challenge, but it is also a chance that Russia must not miss, although currently we are just beginning to comprehend the full magnitude of the problem, let alone envisage a solution.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |