The Migration Angle of the 2008 Global Crisis

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Doctor of Economy, Professor, Professor, Member of the Global Migration Policy Associates

The global economic crisis which ravaged the world in the second half of 2008 affected all the regions of the world to various extents, and provoked new debates on the effects of migration on nations, on migration flow management and on migrant rights. It was migrants who became the first targets of redundancies in autumn 2008. The impact of the crisis was felt in Russia as well, and anti-migrant sentiments significantly affected the principles of Russian migration policy.

The global economic crisis which ravaged the world in the second half of 2008 affected all the regions of the world to various extents, and provoked new debates on the effects of migration on nations, on migration flow management and on migrant rights. It was migrants who became the first targets of redundancies in autumn 2008; they who were named the main culprits behind rising unemployment among the indigenous population; they who were victimized by employers with the payment arrears and worsening labour conditions which became standard practice during the crisis [1]. The impact of the crisis was felt in Russia as well, and anti-migrant sentiments significantly affected the principles of Russian migration policy.

The focus of global debate on migration in the pre-crisis period: migration as an asset for development

It is essential to note that for several years preceding the global crisis, there was intense interest among the countries involved in international migration processes in exploring the benefits of migration for development. This period was marked by attempts to develop and institutionalize the best modes of mutually beneficial cooperation between the donor nations and the recipient nations. In the middle of the 2000s, discussions on migration as a significant asset for development were elevated to the highest international level, becoming part of the United Nations agenda. In 2006, the so-called High Level Dialogue on Migration and Development under the auspices of the UN General Assembly took place, preceded by wide-scale research work conducted by the “Migration and Development" Global Commission, and also by several regional fora, etc [2]. UN General Secretary Ban Ki-moon made a report on “International Migration and Development” with the central message that global migration is an ideal tool to facilitate mutual development, which is to say coordinated and consistent improvement of the economic environment, both in the regions which donate migrants and the regions which absorb them, on a basis of complementarity and equilibrium [3].

Starting in 2007, the global debate on the opportunities and consequences of migration was institutionalized within the format of the Global Migration and Development Forum (GMDF), an informal consultancy providing a platform for discussion on matters of international migration, and for an exchange of best practices on migration and development (including migration trends, the impact of migration on donor nations and recipient nations, migrants’ rights, gender issues, integration etc [4]). This tendency to present migration as positive phenomenon was supported by certain new factors, primarily the escalation of global migration, new nations being drawn into these processes, increased financial flows (remittances) from migrants as “guest-workers” to their home countries which surpass other external sources of budget revenues, and an increase in the number of actors getting involved in the management of migration on national and international levels.

According to UN data, in 2008 the number of international migrants in the world (defined as people living outside the countries of their birth), exceeded 214 million, a three-fold increase from 1960 (75 million) [5]. The overall number of migrants engaged by the labor market in the countries where they reside, according to International Labour Organization (ILO) data, is almost 100 million, or 3% of the total global workforce [6]. In Western Europe, for instance, migrants form on average 10% of the workforce [7].

In the second half of the 2000s, donor nations displayed an intense interest in reaping the benefits of global labor migration. Access to foreign labour markets for their more-or-less surplus workforce reduces their unemployment statistics, increases social stability and provides an impetus to the economic development of the donor nations. By exporting their workforces, donor nations ensure the return of financial resources through remittances by the migrants. Over the two decades preceding the global crisis, the aggregated financial flows from migrants in developed countries to developing nations went up from $31 billion in 1990 to $77 billion in 2000 and then to $336 billion in 2008. In 18 years the volume ofremittance surged tenfold! [8] In the interval between 2000 to 2008, the annual growth of global remittances was 18% [9]. Migrants' remittances have become one of the major global financial flows. The benefits for the donor nations are not limited to the improvement of living conditions of migrants' households: this money becomes a stimulus for macroeconomic improvement of the financial state of these countries, serves as an investment resource pool for business and sets the stage for the growth of the entrepreneurial class.

Consequently, at the beginning of the 21st century international migration, mostly workforce migration, can be considered as more than a function of the international labor market. It has rapidly become an integral structural part of the global economy, and expands the interdependence of nations in the epoch of globalization with a new dimension, migrational interdependence. For both donor nations and recipient nations, it has become an essential and sometimes only resource of economic development.

The challenges of the global crisis

The impact of the 2008 global crisis on global migration, experts claim, was both strong and far-reaching when compared to other economic cataclysms after the Second World War [10]. The crisis downsized migration, in particular labor migration, changed its geography, affected the volume of remittances and living standards of the migrants and their families, and also provoked xenophobia. Despite forecasts, most of the migrants chose not to return home, even having lost their jobs, but stayed in the recipient country in the hope of finding some other source of income, and a quick recovery of the labor market. The crisis in 2008-2009 was global in its outreach and left no alternatives for the migrants to seek jobs elsewhere, as was an option during the 1997-1998 crisis in Asia when migrants moved to countries least affected by the crisis [11]. The subsequent crisis significantly decreased the volumes of remittances. In 2008 compared to 2009, remittances from the migrants went down by $20 billion, that is more than 6% [12]. Nevertheless, these remittances remained an essential and, vitally, relatively stable source of finances for the donor nations while other sources like loans, private investments and official aid programs were far more drastically reduced.

Frozen investment projects in the less developed countries, which are primarily migrant donor nations, had a highly negative impact on their labor markets. Having lost the chance to find jobs at home, people sought job opportunities abroad, consenting to unfavourable terms and conditions of employment, often bypassing official channels to leave the country, and sometimes putting their health and even lives at risk.

Experts have noted that under the dire conditions of the crisis migrants displayed a higher ability to adapt to the deteriorating situation of the labor market than native people. They were ready to accept pay cuts, a lowering of their social status, and worse living conditions, because return home, where the labor market was even worse, was not an option. Lack of viable alternatives makes migrants far more flexible participants in the international labor market. The following statistics support this conclusion. In the USA, where before the crisis one in every six workers was a migrant, during the crisis every other newly employed worker was foreign-born. In the UK, the data are even more telling: seven out of ten new workers were migrants [13].

The crisis affected the construction business most severely, as it absorbs 40% of all labor migrants in the world, and mostly low-qualified workers. In the USA, out of three million Hispanic workers employed in the construction industry, two million are migrants. They made up the majority of the 300 thousand construction workers made redundant in 2007-2009 [14].

Crisis management: the government response

In 2008-2009, most recipient countries resorted to measures aimed at reducing the inflow of migrants, and stimulating their return home in order to protect the domestic labor market and preserve jobs for the local workforce. The tools used for this purpose varied. In most cases, they reflected the growing protectionist trend and were aimed at restricting the entry conditions for foreigners and cutting down the number of migrants. In Australia, Italy, South Korea, Spain, and Russia, lowering the quota for foreign labour migrants was applied as a crisis containment measure. In the UK, New Zealand and Australia, the list of "most wanted" professional trades regarding migrants was also reduced. In the USA, Norway, Ireland, Czech Republic, Australia and New Zealand, employment procedures were revised to favor local workers. Spain, Czech Republic, France and Japan introduced financial bonuses for migrants who agreed to return home and not come back for a period of time ("pay-to go") [15].

However, it should be noted that during the global crisis, and despite anti-migrants sentiments within society, many nations kept their doors half-open for migrants and even introduced new simplified rules of entry for foreigners. For instance, at a referendum held in February 2009 the citizens of Switzerland approved an “open door” policy for residents of EU countries. In December 2008, Sweden allowed more freedom of maneuver for local companies to employ foreigners. In 2009, the Czech Republic launched the Green Card system for migrants. Poland simplified the procedure of employment for seasonal migrant workers. In Luxembourg, Netherlands and Norway, work and residence permits were merged into one ID document [16].

All these facts point to the conclusion that the governments of the developed nations view the use of migrants as a resource as a long-term strategy due to the aging of the local population and chronic shortages on the domestic labor market.

At the same time, the crisis forced the governments of the recipient nations to revise the earlier notion that the migrant workforce was a temporary resource. Previously, it was considered common wisdom that migrants make up for a deficit of labor force at times of economic growth, and can be dismissed at times of crisis. It has been proved that the elasticity of this labour market segment had been overestimated: even with rising unemployment, migrants remain in demand because locals, even amidst a crisis, do not consent to fill many of the vacancies considered suitable for migrants.

We can see from this that the current international labour migration trend is of a structural nature and is only relatively prone to periodic fluctuations [17]. The reason for this peculiarity is rooted in the demographic factor, in the aging and diminishment of the population in all major developed nations, and also in the fact that the local workforce either does not possess the necessary qualifications, or is reluctant to perform certain types of jobs which could be done by low-qualification or unqualified workers [18].

The global crisis has two dimensions that must be taken into account by the governments of the recipient nations in correcting migration policy.

First, there are the anti-migrant sentiments in recipient nations leading to social tension. Protest actions against the employment of foreigners in EU countries led to initiatives to amend the legal framework regulating the free flow of the labor force within Europe [19]. This proves that the extent of tolerance of the recipient societies does not live up to the politicians' official statements. Yet the blame for undermining social cohesion has been placed on the shoulders of the migrants, and the multiculturalism policy, applied in Europe and in some other countries around the globe, has been declared, in the words of the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, to have “unequivocally failed” [20].

Second, it has been observed that the hardening of migration legislation in most of the recipient countries, justified as an anti-crisis measure, has inevitably provoked a rise in illegal migration and unregistered employment. This is due to the deterioration of the economy on a global scale, especially in the less developed countries which serve as the main source of labor migrants. According to expert estimates, illegal immigration in Russia soared as a result of tougher work permit regulations for citizens of the CIS countries and the decrease in the migrant quota in 2009 [21]. Consequently, there was a rise in migrants’ rights violations, their working conditions deteriorated, and, in general, the exploitation of migrants rose significantly. At times of crisis, illegal migrants serve the purpose of saving on wages and salaries, helping maintain the competitiveness of a business. In reality, however, it leads to a bloated “grey sector” of the labor market, contempt for the law, unfair competition, and the overall deformation of established relations in the economy. Furthermore, the rise of illegal migration devalues the government’s efforts to manage labor migration, and is also detrimental to national security interests.

The two trends mentioned above are dangerous not only because they represent features of the global crisis, but because they act as additional destabilizing factors with the potential to have negative effects even in the post-crisis period. In addition, the rise of anti-migrant sentiments within society and the danger of an uncontrollable flow of illegal migrants provoke the governments to act on impulse and resort to populism by hardening policy towards foreign workers. As a result, migration policy loses its rationality, predictability and long-term character, while sending confusing signals both to the society of the recipient nation and to the migrants within it.

The crisis has demonstrated the growing interdependence of all nations, and underlined the importance of coordinated action on the state level at times of recession; in particular, the need for action related to labor migration. Protectionist measures aimed at shielding nations from global problems can actually lead to widespread instability, whether globally or in individual regions. Massive deportation of labor migrants can lead to a dramatic fall in revenues for their families, pushing certain social groups to the margins and setting the stage for social upheaval in the donor nations - which, among other things, may trigger new waves of refugees.

Russia and the CIS: subversion of global trends

Throughout the 2000s, Russia enjoyed sustainable GDP growth and a stable demand for labor, including labor migrants. In 2008 alone, Russian authorities issued official working permits for more than 2 million labor migrants; they have become an important part of the workforce for employers in Russia, and in some industries a vital element of stable functioning. For instance, the foreign labor force invited into the Russian construction business in 2005-2008 increased 3.5-fold. “Guest workers” enabled certain large, medium and small enterprises to boost competitiveness, facilitated the emergence of new types of business and reduced the number of bankruptcies.

The reforms of the Russian migration laws in 2006-2007 were a de facto switch to an “open door” policy for CIS migrants since there were no visa requirements, as demanded by Russia's demographic and economic interests. In the span of two years, these reforms provided for a four-fold increase in the number of CIS legal labor migrants [22]. In fact, it amounted to a major step by Russia towards the creation of a unified regional labor market in the post-Soviet space.

For the post-Soviet states, the export of labour, primarily to Russia, became an efficient way of alleviating social tension, reducing unemployment and poverty, and increasing the income of the population. The enhanced remittance flows have improved the macroeconomic financial state of these countries. World Bank data show that in 2007 remittances formed 36.2% of the GDP in Tajikistan and Moldova, and these figures were the highest in the world. In Kyrgyzstan remittances from labor migrants formed 27.6% of the GDP, which exceeded foreign development aid 2.4 times [23]. It should be noted that statistics keep track only of money transfers executed through official channels — through banks, remittance mechanisms, and postal transfers. In reality, a significant portion of money is being sent home by labour migrants unofficially — through friends, relatives, neighbors and railway carriage attendants, and also delivered personally. The actual final count of these money flows from labour migrants to their home countries should be doubled [24].

It is evident that money received in Russia is mostly spent on migrants’ household needs: food, clothes, health, purchase of real estate, education for children. On top of that, migrants display an interest in starting businesses of their own. The recent study by the World Bank regarding Eastern Europe and Central Asia shows that 26% of migrants open their own business after returning home [25]. An opinion poll conducted by the Chamber of Goods Producers and Entrepreneurs of Uzbekistan [26] showed that every second former labor migrant used working abroad to accumulate initial capital to open a business of his/her own; one third admitted that it helped them broaden their scope of understanding of business realities. Thus, labor migration facilitates the formation of an entrepreneurial class in Central Asian states, which creates new jobs for other labor migrants returning home, as well as for those who never left [27].

The advantage gained by donor nations through their migrants’ experience in Russia forced their governments to reassess the potential of intra-regional labor migration. In the pre-crisis years, the issues related to the export of the labor force became part of the economic strategy for some countries in Central Asia and the Caucasus (Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan); efforts were intensified to either sign bilateral agreements on labor migration (Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan) or to add value to existing ones (Armenia); a new practice emerged of signing direct deals with Russian companies interested in accommodating foreign labor (Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan); an official migration infrastructure started to emerge in the form of inter-governmental migration centers, “migration bridges”, public and private job centers, recruitment agencies, etc [28].

Russia: acting on impulse versus following strategic priorities

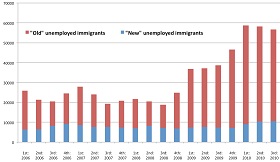

The global crisis hit Russia at the end of 2008 and led to lower demand, reduced production, redundancies and a rise in unemployment. According to official data by the Ministry of Health and Social Development, in the last quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009, the number of registered unemployed in Russia went up three-fold and exceeded 2 million. The deterioration of the Russian labor market affected the demand for foreign workers by Russian employers. By the end of 2008, the home-bound outflow of labor migrants constituted one million people, although experts emphasized that this was linked not only to the consequences of the crisis but to the seasonal drop in demand for workforce [29].

The Global economic crisis aggravated the issues around bringing foreign workers to the Russian labor market. At the end of 2008 and in early 2009, suggestions were made in the government, various agencies, trade unions and mass media [30] to introduce a visa regime with the CIS countries, ban third-party job finding for foreign nationals, deport migrants who find themselves unemployed and veto foreign labor migration, which demonstrated the existence of strong opposition to the notion that migration can be a positive factor for the strategic development of contemporary Russia.

Quite a number of the proposals initiated during the crisis made their way into the reformed laws on migration in 2009-2010. However, on the whole, the upper hand was gained by the rational approach, rather than simple hardening of the migration policy. Yet on several occasions the authorities acted on impulse, without due regard for arguments put forward by the expert community. For instance, the decision taken in December 2008 to cut the quota for foreign workers in 2009 was populist in nature. To prove this point, it is sufficient to mention that there were no concrete actions taken to implement the decision to oust foreigners out of the domestic labor market. Nevertheless, in the post-crisis period the concept of introducing quotas was applied as a tool not so much of economic but of political nature, thus neglecting the demand of the Russian economy for a foreign workforce.

During the crisis the authorities did not dare to deport illegal migrants en masse, and this should be viewed as a positive outcome of the measures taken in response to the acute debate on whether Russia needs migrants at all. There must be several reasons for such a “moderate” attitude from the Federal Migration Authority (FMA).

First of all, the persistent joint actions of the experts’ community and the authorities produced an understanding that the demographic crisis in Russia is of a long-term nature, as well as of the chronic deficit of workforce in a number of industries, which can be reduced only through the use of foreign migrants. For this reason, any drastic measures during the crisis aimed at foreign labor migrants could have led to a negative effect for the labor market in the post-crisis period.

Second, Russia's geopolitical interests demand efforts to maintain social stability in the post-Soviet region. By allowing migrants from former-USSR republics into its domestic labor market, Russia ensures the security of its borders. Russia realizes that a massive return home by migrants might trigger social instability in the countries of the “near abroad”, and for this reason Russian authorities chose to downplay the issue and allow migrants to weather the crisis in Russia and provide for their families at home with remittances, albeit more modest ones. Time proved this policy to be correct: social breakdown in the CIS countries was averted despite the deterioration of the economic situation in the whole region, and migration ties between Russia and its major migrant-donating partners were preserved.

Third, Russia has a stake in promoting integration processes in the post-Soviet space, where it has all the prerequisites to be the regional leader, and perform its paternalistic mission vis-a-vis states and nations which used to be part of the Russian Empire and then of the Soviet Union, and for whom Moscow has been setting the course of development and determining the way of life for centuries. Labor migration has been one of the dominant factors of integration between sovereign states. Attempts to harshly dispose of the citizens of CIS countries residing on the territory of Russia would be a betrayal of former compatriots and contemporary regional partners, and it would have a highly negative effect on Russian foreign policy in the region, and be detrimental to the processes of integration.

It is likely no coincidence that precisely in the autumn of 2008, amidst the anti-migrant sentiments provoked by the crisis, the Federal Migration Authority (FMA) for the very first time made an assessment of the contribution of the migrants to the national economy. The head of the FMA, K.O. Romodanovsky, admitted that the foreign workforce from the CIS countries should be credited with generating 6-8% of the national GDP [31]. Lamentations about remittance by foreign migrants largely ceased after the head of FMA said that “for every dollar earned by guest workers in Russia the national budget gets up to 6 dollars.” This official stance taken by the FMA helped cool the anti-migrant rhetoric of the politicians and the media.

To conclude, the corridor of policymaking which would simultaneously correspond to the mood of society and yet not contradict Russia's objective demographic and geopolitical interests was relatively narrow. It was apparent that the stance taken by Russia in its migration policy under the force majeure circumstances of the global economic crisis would define the future economic, social and political situation in the whole post-Soviet space. The official position articulated by the head of FMA K.O. Romodanovsky was crucial in this respect: “…no drastic decisions should be taken. Migration processes are a finely tuned phenomenon, and should be managed in the most delicate way” [32].

The Russian migration reforms of 2009-2010 as a response to challenges of the global economic crisis

The crisis further stimulated Russia and other CIS countries to sort out the migration processes in the region. Beginning at the end, it should be admitted that this did not improve the situation in terms of reducing the irregularity of migration processes, scaling down illegal migration, eradicating practices of migrant exploitation or ensuring the observation of their labor and social rights. Nevertheless, some of the corrections made by Russia to its migration policy in response to the global economic crisis’s challenges can be defined as the application of a rational approach to the management of migration.

1. Aside from the decision taken in December 2008 to cut down the quota for foreign workers in 2009 [33], aimed at mitigating anti-migrant sentiments and preserving peace within the country, there was another decision regarded by some researchers as a setback, one which reverted the situation to the state of rigid migration policy preceding the liberal reforms in 2006-2007 [34]. This decision related to the issuance of working permits for migrants from CIS countries enjoying a visa-free regime with Russia. The FMA instruction dated 26 February 2009 [35] stipulated that the work permit for a migrant now expired after 90 days (a “short” permit). In this time span, the migrant could look for an employer and change employers in search of a permanent job. In case the migrant failed to find an employer ready to sign an employment contract (provided this employer took part in the bidding procedure and his bid was included into the annual quota for the current year), the migrant had to leave the country. If the migrant found a suitable job with an employer who had the right to enroll a foreign worker within the quota, the migrant presented the contract to the FMA and received a “long” permit for a period of one year from the moment of his entry into the Russian Federation.

This measure de facto amended the law passed in 2006 which enforced the principle of free employment in Russia for citizens of the CIS countries enjoying a visa-free regime with Russia. That system of admission of foreign laborers from the CIS countries to the Russian market required correction. In order to protect the Russian labor market from excessive competition from foreign workers, a system of annual quotas was introduced, determined on the basis of bids presented in advance by employers.

However, the mechanism ensuring that migrants from the visa-free regime countries would end up with the employers who took part in the bidding procedure had not been fully developed. Sata compiled in 2008 show that, often, by the time employers involved in the bidding procedure had a need to fill in vacancies with foreign laborers, the quota had been exhausted and the migrants who had moved in on its basis were already employed by other companies who might not have registered with the quota programme.

There were two options for dealing with the issue: first, to cancel the quotas and institutionalize the principle of free labor movement for CIS migrants; second, to preserve the quotas as a symbolic tool of control over the scale of labor migration, but introduce limitations to free employment of migrants in Russia. Given the global crisis and the tight labor market in Russia, the first option could have had grave social repercussions, which left the second option as the best one under the circumstances. Thus, the authorities opted for the second option.

The amendment of the law could have been considered a more or less rational solution, had its implementation not led to artificial complications and rising costs of issuing work permits for CIS visa-free migrants. These complications blocked transparency, enhanced the position of shady dealers, and favored various corrupt schemes of employment. Legal violations in hiring migrants have once again become common practice on the Russian labor market [36]. Even fines applied to employers for illegal employment of foreign workers (up to 800,000 rubles for each employee!) have turned out to be a weak barrier to illegal migration, since it is possible to bribe the migration officers for a lesser sum.

In 2010, a system of patents was introduced at

the labor market for private individuals

Moreover, the requirement for the employer to participate in the quota bidding procedure essentially sidelined small businesses and private entrepreneurs who could not meet these demands [37],and also private citizens who employed foreign workers. The awkward attempt to adjust the migration laws led to a surge in unregistered employment. The core reason, it seems, lies in the fact that the bureaucracy of the migration authorities was ideologically opposed to the liberal policies affirmed by the laws adopted in 2006-2007.

2. With that said, the rise in illegal migration recorded by experts forced the FMA to find new methods of cutting the number of illegal migrant laborers. A radically new concept was put forward for the illegal migrants employed by private citizens, who constituted nearly half of all illegal migration in Russia according to the head of FMA K.O. Romodanovsky [38]. In 2010, a system of patents was introduced at the labor market for private individuals.

The idea of a patent amounted to the following: migrants who intended to work for Russian private citizens in the capacity of household maid, sick-nurse, nanny, cook, gardener, or on short-term jobs doing repairs, refurbishment, etc., would be legalized by buying a patent for the right to work for an upfront payment of 1000 rubles a month. The validity of the patent was to be prolonged automatically after receiving by mail the confirmation of the payment through a bank. According to the official FMA data, after 18 months of this practice (data recorded through January 2012), almost one million patents had been sold in this way. Yet it remains unclear to what extent this measure helped reduce the number of illegal labor migrants, estimated at 4-5 million: there is no system to monitor and control employment by private individuals, who are not obliged to inform the authorities about having employed a foreign worker. The main advantage of the system of patents is that it is the most simple and comprehensible method of legal employment for the migrants.

Nevertheless, the FMA statistics for 2011 indirectly indicate that this simple method is being used not only by migrants employed by individuals, but also by those working for business entities — at construction sites, markets etc. In several regions of the Russian Federation, the number of purchased patents far exceeds the fixed quota on work permits for that region, while the quota itself is not used to the full.

Thus, the innovations in the migration policy of Russia introduced as part of anti-crisis measures, and aimed at reducing the number of illegal migrants, are vulnerable to criticism. There are also unaddressed issues regarding the lack of compulsory medical certification of migrants who simply purchase the right to legally stay and work in Russia, actual tax payments, control and monitoring tools, etc.

3. In 2010, the migration laws of Russia were amended to incorporate another clause which could be viewed as an indirect consequence of the global crisis. The crisis seriously affected the Russian economy. The Russian GDP reduction of 7.3% was the most dramatic among the G20. The need to stimulate growth against the tightening of global competition shifted the focus to the modernization of the national economy, with innovation at its core. However, innovation requires human resources to back it up, as well as the introduction of new technologies, attraction of investments, and building up modern production facilities In terms of migration policy, this course of action requires the creation of the most comfortable working and living conditions for foreign highly qualified personnel, investors and representatives of transnational corporations. All of them were targeted by the reformed migration policy [39].

One thing should be made clear: highly qualified human resources are the object of tough competition between recipient nations. Many developed and developing nations have come to realize the benefits of attracting foreign scientists, engineers, managers, lecturers and other professionals, which basically means importing know-how; it happens to be extremely lucrative for the national economy [40]. For this purpose, migration laws are amended, special programmes are introduced targeting highly qualified personnel, foreign students are attracted for studies and post-graduate studies and conditions are set to facilitate their employment afterwards, international research collectives are formed, and migration related to investment into priority industries is promoted [41]. As was underlined previously, the crisis led the nations involved to understand that migration as a resource can effectively be used to maintain their global competitiveness.

The new element in managing high skill migration to attract foreign professionals to Russia was articulated by President D. Medvedev (2008–2012 — editor’s note) at the start of the crisis in autumn 2008 and was focused on “head-hunting in Russia and abroad” [42]. According to data collected by the Russian Ministry of Economic Development, “to achieve a modernization breakthrough in the economy there is a need to accommodate some 40-60 thousand foreign professionals annually” [43].

Preferential treatment serving to attract foreign highly-skilled migration covers not only migrants themselves but their employers as well. It comprises the following terms and conditions: 1) the work permit is issued not for a period of one year but for three years, with unlimited extension; 2) if the work is performed on the territory of several regions of the Russian Federation, the work permit covers all of these territories; 3) if requested, highly-skilled migrants and their families get residence permits; 4) a multi-entry visa is provided for the duration of the working contract; 5) income tax for highly-skilled migrants in Russia is fixed at 13% from their very first working day (unlike other labor migrants in Russia, who have to pay 30%). As for employers who attract high skill migrants, they do not have to receive permission from the authorities and do not have to participate in the bidding procedure because highly-skilled migrants are not subject to quota restrictions. In 2011, as a result of this preferential treatment some 10 thousand highly-skilled foreign professionals were employed in Russia.

It is no secret that the new regulation of highly-skilled migration is aimed at improving the investment climate in Russia, since the final investment decision often depends on the capacity for smooth transfer of the necessary personnel to a certain country (top managers, specialists, financial directors, etc). The correction of the migration legislation in this respect should be considered rational and economically expedient.

4. The rise of anti-migrant sentiments in Russian society against the background of the global crisis was similar to what happened in other recipient nations. There is a vast difference, however. The outbreak of xenophobia in Europe caused shock among the authorities because it revealed the ineffectiveness of the long-running policy of migrant integration and promotion of tolerance and capacity for living together in a now-multicultural society. In Russia, growing inter-ethnic tension was a natural consequence of the state's neglect of migrant integration . The issue of migration was used to stir up public feeling, and exploited in political rhetoric, which led to an unacceptable increase in nationalism within society. In 2008, the number of murdered migrants doubled compared with the previous year [44].

Public opinion polls regularly conducted by the Levada Center showed that in 2008 almost half of the citizens of Russia were convinced that “Russia has no need neither of migrants as such, nor of labor migrants” [45], while in the following years the general attitude to migration and migrants kept becoming even more negative [46].

These developments forced the authorities to admit that migration policy must be comprehensive and must include as a priority certain programmes of migrant integration, implying that this is a two-way street and that both the recipient society and the migrants should make steps towards each other. In 2010, a department on integration was set up within the Russian FMA. This was considered a promising move. However, it should be noted that integration is a special area of migration policy where the state cannot achieve success all on its own, moreso if it implements this policy through an institution without any experience in humanitarian interaction with the migrants. The state should have the courage to delegate part of its functions on migrant integration to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) — migrants’ associations, human rights organizations and structures set up by diaspora which are more adapted to performing this painstaking and individual-focused work. There are doubts that the FMA, which preserves its ideology of a closed power center in its own right, will go for it. At the same time, it is all too clear that without broadening of the spectrum of participants implementing migration policy, and without the NGOs, the goal of integrating migrants is doomed to failure.

In conclusion, the reforms of the migration laws in 2009-2010, which can be considered a response to the global economic crisis, do not appear sufficiently coherent, and are controversial in view of their consequences. At the same time, these reforms reflect movement in the direction of a Russian migration policy which would manage migration flows to the country's benefit. In order to turn the legislative changes into a foundation for forming a new model of Russian migration policy, the following are required: 1) they should be coherent and serving a single public goal; 2) they should be consistently implemented within law enforcement practice; 3) they should be explained to the general public and enjoy if not support, then at least understanding within society.

References

1. The Impact of the Global Crisis on Migration. The IOM Policy Brief. Memorandum № 1. January 12, 2009.

2. Migration in an Interconnected World: New Directions for Action. Report of the Global Commission on International Migration. 2005.

3. Report of the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon at the Sixtieth session of the UN General Assembly, International Migration and Development. 18 May 2006.

4. URL: http://www.gfmd.org

5. Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2008 Revision, UN database, POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev. 2008. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2009.

6. The ILO defines the total number of the global workforce as all persons of 15+ age with a job or in search of a job. (A Rights Based Approach to Labour Migration. Geneva: International Labour Organization. 2010).

7. World Migration Report 2008: Managing Labor Mobility in the Evolving Global Economy. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Migration, 2008.

8. World Bank. Migration and Remittances Factbook. 2008.

9. Migration and Development. World Bank. Brief 12, 23 April 2010.

10. M.Fix, D.G.Papademimetriou, J.Batalova, A.Terrazas, S.Yi-Ying Lin, and M.Mittelstadt, 2009. Migration and the Global Recession. Migration Policy Institute and BBC World Service. September 2009; Global Employment Trends Update. Geneva: International Labor Organization, 2009.

11. Martin P. The Recession and Migration Alternative Scenarios. A Virtual Symposium, Migration and the Global Financial Crisis, organized by Stephen Castles and Mark Miller, February 2009. URL: http://www.age-of-migration.com/na/financialcrisis/updates/1c.pdf

12. MPI. The Global Remittances Guide. 2010: URL: http://www.migrationinformation.org/DataHub/remittances.cfm

13. M. Fix, D.G. Papademimetriou, J. Batalova, A. Terrazas, S. Yi-Ying Lin, and M. Mittelstadt. Migration and the Global Recession. Migration Policy Institute and BBC World Service. September 2009.

14. Martin P. The Recession and Migration Alternative Scenarios, URL: http://www.age-of-migration.com/na/financialcrisis/updates/1c.pdf ; A Virtual Symposium, Migration and the Global Financial Crisis, organized by Stephen Castles and Mark Miller, February 2009.

15. Koser K. The Impact of the Global Financial Crisis on International Migration // The Whitehead Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations. 2010. Vol. XI. № 1.

16. International Migration and Development. Report of the Secretary-General of the United Nations. A/65/203. 2010. 2 August.

17. Awad I. The Global Economic Crisis and Migrant Workers: Impact and Response. Geneva: International Labor Organization. 2009.

18. World Migration Report 2008: Managing Labor Mobility in the Evolving Global Economy. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Migration, 2008.

19. Gow D. European commission rules out change to law on free movement of workers. Contested EU legislation lies at heart of wave of strikes against foreign employees across continent // The Guardian (U.K.). 2009. February 2.

20. Sinico S. and Kuebler M. Chancellor Merkel says German multiculturalism has ‘utterly failed’ // Deutsche Welle. 2010. 17 October. URL: http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,,6118859,00.html

21. Chudinovskikh O.S. On the possible impact of crisis on international migration flows to Russia. 2009. URL: http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2009/0363/analit04.php It should be noted that in the United States a different trend emerged: throughout 2009, there was a dramatic decrease in the number of illegal migrants attempting to cross the border, resulting from deterioration of the labour market making it less attractive to potential migrants, and also from hardening of border controls and introduction of other measures against illegal migration (M. Fix, D.G. Papademimetriou, J. Batalova, A. Terrazas, S. Yi-Ying Lin, and M. Mittelstadt. Migration and the Global Recession. Migration Policy Institute and BBC World Service. 2009. September. Р. 19–20).

22. Monitoring of Legal External Labor Migration, 2006-2007, FMA of Russia. Moscow, 2008.

23. World Development Indicators Database. World Bank, September 2008.

24. Sukhova Yu. 2007. Remittance, a contribution to economic development. URL: http://www.finam.ru/analysis/forecasts006BF/default.asp

25. Willem van Egen. Migration management policy options. World Bank. Eastern Europe and Central Asia Regions. URL: http://gdln-migration.googlegroups.com/

26. Maksakova L.P. Migration and labour market in Uzbekistan // Migration and labour market in Central Asia/ Under the editorship of Maksakova L.P. Moscow – Tashkent. 2002. Pages 10-26.

27. Tyuryukanova E.V. Remittances: misfortune or benefit? URL: http://www.polit.ru/research/2005/11/30/ demoscope223_print.html

28. For additional information see: Ivakhnyuk I.V. Eurasian migration system: theory and politics. Moscow. Moscow State University, MAKS Press. 2008.

29. Zhdakaev I. ‘Unwanted Workforce’ Scheme // Kommersant-Money. 15 December, 2008.

30. For additional information on the stance and initiatives of the Russian legislative and executive branches of power, trade unions, business and analysts amid the global economic crisis see: Ivakhnyuk I.V. Impact of the economic crisis on migration trends and migration policy in the Russian Federation and the region of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. World Migration Organization (WMO). Moscow bureau of WMO. 2009. Pages 48-62.

31. Romodanovsky K.O. Pave the way to the future with deeds. 2008. URL: http://www.fms.gov.ru/press/publications/news_detail.php?ID=26698

32. Romodanovsky K.O. On attracting gastarbeiters in the new economic environment: URL: http://ialm.ru/pages/111/id229.html

33. Postavnin V.A. The delusion of simple solutions // Migration in XXI century. 2009. № 3–4.

34. Zayonchkovskaya Zh., Mkrtchyan N., Tyuryukanova E. Russia and the challenges of immigration // Zayonchkovskaya Zh.A., Vitkovskaya G.S. (editorship). Post-Soviet transformations: reflected in migration. Center of migration studies. Institute of public economy forecasts, Russian Academy of Sciences. Moscow. Publishing house Adamant. 2009.

35. FMA of Russia decree dated 26 February 2009 “Some issues related to the issuance of work permits to foreign citizens who came to the Russian Federation under the visa-free regime”. URL: http://www.consultant.ru/online/base/?req=doc;base=LAW;n=86774

36. Postavnin V.A. You cannot say “Stop!” to a tsunami // Novaya gazeta. 16 September 2009. № 102. URL: http://www.novayagazeta.ru/society/43573.html

37. Voronina N.A. Migration legislation in Russia: state of play, problems, prospects. Institute of state and law, Russian Academy of Sciences. Moscow. Publishing house Sputnik. 2010. Page 186.

38. URL: http://www.oprf.ru/newsblock/news/2325/chamber_news?returnto=0&n=1

39. Federal Law № 86 dated 19 May 2010 “Introduction of amendments to the Federal Law “Legal status of foreign citizens in the Russian Federation”

40. Sobolevskay A.A. Popov A.K. Postindustrial revolution in labour. Moscow. Institute of world economy and international relations, RAS. 2009; Liebig T. A new phenomenon: the international competition for highly-skilled migrants and its consequences for Germany. Bern: Haupt, 2005.

41. Chaloff J. and Lemaitre G. Managing Highly-Skilled Labour Migration: a Comparative Analysis of Migration Policies and Challenges in OECD countries // OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers. Paris, 2009; The Global Competition for Talent: Mobility of the Highly Skilled. OECD. Paris. September 2008.

42. Russian President D.A. Medvedev’s address to the Federal Assembly, 5 November 2008.

43. Speech by Russian Deputy Minister of economic development A. Yu. Levitskaya “On attracting high skill professionals for modernization of the Russian economy” at a broad meeting of the Federal Migration Authority 29 January 2010. (Report of activities of FMA Russia in 2009. Collection of materials from the broad convention of FMA Russia 29 January 2010. Moscow. FMA Russia, 2010. Page 44).

44. Migration in XXI century. 2009. № 5–6. Page 12.

45. Public opinion – 2008. Annual report. Yuri Levada Analytical Center (Levada Center). Moscow. Page 124.

46. Public opinion – 2011. Annual report. Yuri Levada Analytical Center (Levada Center). Moscow. Pages 132-133.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |