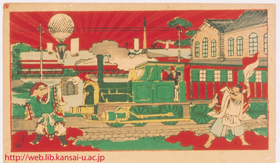

Japan has a significant history of applying soft power since it emerged as a player on the global political stage in the mid-19th century through U.S. efforts to force its inclusion in key processes underpinning international relations. Made to enter into a series of inequitable treaties, Japan set itself the goal of joining the international community on an equal footing. To this end, a modernization project was launched under the ideological slogan Wakon-yōsai (Japanese spirit and Western techniques), which meant borrowing and applying Western knowledge, while preserving the traditional Japanese mindset and worldview. Stepping up contacts with Western powers, Japan has consistently used the tools of soft power, i.e. its truly unique culture, language and traditions.

Soft Power in Current Japanese Policies

The image of a mysterious and picturesque country engulfed in the incomprehensible Japanese spirit was brilliantly constructed inside Japan for international audiences. The program became extremely attractive and eye-catching for the West, providing Japan with a beachhead for the energetic promotion of its culture and language studies abroad. Today, these activities would be considered cultural and intellectual exchanges.

The idea of using soft power efficiently is gaining ground within Japan: the country is increasingly willing to step up engagement with the global community on this basis and increase investment in cooperation along these lines [1]. First, Japan works to create the image of a peace-loving country in which pacifist attitudes are dominant. The Japanese invariably underline their commitment to the 1947 Constitution, specifically Article 9 that stipulates the rejection of war as a sovereign right of the nation, as well as the rejection of the use or a threat of use of military force as a means for the settlement of international disputes. This point is especially significant for its relationships with East and South East Asian countries, which historically associate Japan with militarism and aggression. Advocating worldwide nuclear weapons cuts, Japan presents itself as a nonnuclear state committed to the three nonnuclear principles adopted by the Japanese government in 1968, i.e. no possession, production, or deployment of nuclear weapons within its territory. As part of this soft power, Tokyo also attaches great importance to the Official Development Assistance (ODA), which is perceived as a success. For example, in 1994-2004 Japanese allocations to the International Development Assistance Fund accounted for one-fifth of the total amount [2].

Certainly, Japanese soft power to a great extent relies on the advancement of culture as an intrinsic part of broader state policy. The goals of Tokyo's cultural policy include: 1) making a feasible contribution to the development of the world’s culture and civilization, and 2) adapting the country to changes resulting from globalization and preserving its national identity.

The Japanese government believes that culture is not only something of great interest inside the country but also a vehicle for the promotion of national interests abroad [3]. Traditionally, great significance is attached to the Japanese language, the promotion of which around the world is seen as a key aspect of soft power.

The Japan Foundation

Japan launched the focused promotion of its language in the 1970s because by the late 1960s the country had grown to be the world’s second largest economy, and was acutely aware of its role and influence in the world as allowing the further projection of its power.

In 1972, the Japanese Foreign Ministry set up the Japan International Cultural Exchange Foundation, or Japan Foundation, a specialized organization with a 100-billion-yen (1.21 billion dollars) budget predominantly engaged in the dissemination of the country’s language and culture abroad. After the Cold War, the Foundation was tasked with becoming a major promoter of the Japanese government's policies [4].

In October 2003, the Japan Foundation obtained the status of an independent administrative organization with its head office in Tokyo and a branch in Kyoto. The Foundation has two subordinate structures, i.e. Japanese-Language Institutes in Urawa and in Kansai, as well as 20 overseas offices in 22 countries.

Currently, the Japan Foundation is one of the world's largest investors in culture integrated into national policy to implement a balanced strategy for investment in Japan's positive image in the world, including Russia [5]. The Foundation's charter stresses that the more people in the world study the Japanese language the better they understand Japan. In order to boost Japanese-language learning, the Foundation finances projects in over 190 countries worldwide, including Russia. Japanese-language institutes and centers affiliated to the Foundation operate in 26 countries. The Foundation sends Japanese-language teachers overseas, assists in organizing Japanese-language exams (nihongo noreku siken), arranges tours to Japan for Japanese-language students and teachers, and participates in developing language curricula [6].

Spreading the Japanese Language Across the World

As a result of the Japan Foundation’s activities, and those of other Japanese organizations actively involved in language promotion, foreigners find themselves increasingly attracted to the Japanese language and consequently to Japanese culture. Currently, Japanese is the ninth most spoken language in the world, i.e. 140 million people with Japan's population of 126 million. According to data from 2007, in the period between 2003 and 2006 Japanese language programs operated in 133 countries - including the new additions of Montenegro, Oman, Qatar, Uganda and the Central African Republic. In 2006, there were 2.98 million students of the Japanese language worldwide, a 25.4-percent growth against 2003 (not including those doing self-study programs). Over the same period, the number of Japanese-language institutes grew from 11.6 to 13.6 percent, and the number of teachers from 33.8 to 44.3 percent.

The Foundation focuses particularly on young people: launching the Cool Japan project in the 21st century to promote the Japanese way of life and youth subculture (anime, manga, pop music, fashion, cuisine, etc.) among young people overseas [5].

The Japanese Language in the Asia-Pacific Region

In the late 1990s, Japan announced a change in its foreign policy priorities, shifting to regional targets in order to raise its international status through an enhanced standing in the Asia-Pacific region. Japan uses dynamic economic engagement and capitalizes on close historical and cultural ties to expand its influence in the Asia-Pacific region and South East Asia. Its advance is bolstered by rhetoric about a common Asian civilizational sense of belonging and the common destiny shared by oriental countries. To strengthen its regional positions, Japan proclaims its readiness to act as a bridge between West and East, presenting itself as the most Western power in Asia. This drive is clearly echoed by the Japan Foundation, which concentrates its language promotion activities in the region.

In 2006, South Korea and China, where Japanese is normally the second language, were the world leaders in learning Japanese with 30.6 and 23 percent of the population respectively engaged in studying it, followed by Australia’s 12.3 percent of the population. The Japanese language is also gaining popularity in the United States and Canada, some Latin American countries, primarily in Brazil and Peru, countries with large Japanese communities. However, 2006-2007 polls in the United States indicated a 15.9-percent drop in the number of Japanese language learners, which accounted for just four percent of the total student body. Japanese is gaining popularity in Russia: although in 2006 learners amounted for just 0.3 percent of the total student body, that figure was 4.6 percent higher than that for the previous year.

The Global Status of the Japanese Language

There are sometimes calls in Japan for the Japanese language to be internationalized by its inclusion as a UN language to counter the dominance of the English language. Some believe that as soon as Japanese becomes international the country will be able to turn into a genuinely great power [7]. This was the rationale that prevailed in the 1980s, when the country was in the midst of an economic boom and trying to gain political weight by balancing its economic and political potentials. Today Japan’s economic and political standing is different, making this great power debate somewhat subdued.

A realistic analysis indicates that making Japanese a UN language in the short- and longer-term future seems unfeasible, since it is practically unused by international organizations, at conferences and symposiums. And the reason for this is purely linguistic, as Japanese differs from European languages in structure, complicated hieroglyphics and some other respects, which makes it difficult to learn and understand.

Can Russia Follow Japan’s Example?

Japan’s experience of using language as a tool of soft power seems quite workable for Russia. To date, Russia has no organization that, in its influence, is equivalent to the Japan Foundation, but with time this function could be taken up by the Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States, Compatriots Living Abroad, International Cultural Cooperation (Rossotrudnichestvo) and the Russian World Foundation, which aims to promote the study of the Russian language abroad. This process would require massive investment and real assistance from the Russian Government, as well as systemic, targeted continuous efforts involving various experts engaged in developing targeted programs, and a network of Russian-language centers to adequately represent Russia in the world.

However, the main conclusion to be drawn from the Japanese experience seems to lie elsewhere. The Japanese are rightfully proud of their culture, language and traditions, and are in no doubt that their country is worthy of both respect and imitation. The pros and cons of this approach may be debatable, but attracting foreigners to learning the Japanese language brings them closer to Japanese values.

Recognized as the language of a great culture, the Russian language has no need to earn additional recognition. Both Russia’s culture and language are already valued and worth promoting abroad. This is something that is often forgotten, even in Russia. However, a slightly different approach needs to be taken in order for Russian to be used as a soft power tool. The international community, and particularly the younger generations, associates Russia today not just with the finest aspects of its culture, but also with successes and achievements, blunders and mishaps in a wide variety of fields. If we are to see improved results, the teaching and promotion of the Russian language abroad should be accompanied by similarly significant activities aimed at forming a positive image of Russia within the country, in order to help generate international esteem and add impetus to this cooperation. This image should be based on those values that are shared by most Russians, in order to construct a foundation for clear-cut and distinct international positions. With this basis laid, the Russian language really does stand a chance of becoming an effective instrument of soft power.

1. A. Tsuneo. The Choice of Soft and Hard Power in National Security Policy of Japan // Pacific Review: 2008-2009, Moscow, 2010, page 42

2. Ibid, page 43

3. O.N.Zheleznyak. The Cultural Policy of Japan Today // Japan of Today. 2009. № 2. page 70.

4. Foreign Policy of Japan: History and Modern Times. Moscow, 2008, page 289

5. O. Kazakov. On the Path of Soft Power // Russia in Asia-Pacific. 2012. № 3(24), page 51

6. A.E. Kulanov. Cultural Diplomacy of Japan // Japan Yearbook 2007. Moscow, 2007, pages 128–130.

7. E.L. Katasonova. Japan: A Challenge to Western Civilization? // Japan: Myths and Reality. Moscow, 1999, page 186