The stage of European Union's straightforward development as a single political and cultural space appears to have ended, which is a logical result considering the series of internal crises that have made many EU members reconsider existing integration paradigms and think about new approaches. However, this is not to say that the European economic area is not expanding. On the contrary, it is vigorously evolving in different directions. These processes will serve as the grounds for the Greater Europe project, while any attempts to establish additional political institutions are unlikely to bear fruit.

Today, Brussels operates as an umbrella for emerging peripheral trade areas in Southern and Eastern Europe, primarily through the Central European Free Trade Association in the Balkans, the Customs Union with Turkey and the intended expansion of the trade area within the Eastern Partnership. This is part of an overall program aimed at creating free trade areas between the EU and various regions of the world. In addition to existing agreements with South Korea, Mexico and South Africa, Brussels is negotiating in various formats over the removal of trade barriers with the United States, Central America, ASEAN, Mercosur, Canada, India, Malaysia and Singapore. The projected extension of the trade area into Eastern Europe triggered tensions between the EU and the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), the latter still being an institutionally weak supranational organization seen by many as an unnecessary competitor in the struggle for the post-Soviet space rather than a partner within Greater Europe. Hence, before analyzing opportunities for Greater Europe, we first need to outline the key issues that are devastating the European arena from within and identify the pillars to strengthen the foundation for a lasting future.

Multilayered European Trade

The economy of Greater Europe of today has emerged as an ongoing history of mergers and assimilation of various economic blocs. Formally, the largest integration union is the European Economic Area (EEA), which is hardly an organization but rather a collection of normative documents designed to bridge the European Union and European Free Trade Association (EFTA), the two biggest European trade amalgamations. At first glance, the difference between the European Union and the EFTA is purely technical. However, the EU is a customs union able to establish a single external tariff which virtually deprives its members of independent trade policies. The EFTA has no such rules, as its members can develop absolutely unrestricted trade relations with any state or region. The EFTA incorporates four countries with an aggregate GDP of 1.14 trillion euro, i.e. Norway, Iceland, Lichtenstein and Switzerland, which do not belong to the European Union and, consequently, to the EU Customs Union (EUCU). As such, Switzerland, the EFTA's undisputed leader, is beyond the jurisdiction of the EEA and prefers to trade with the European Union on a bilateral basis. And this unique Swiss scheme, advantageous for maneuvering between various trade blocs, has made the model attractive for Euroskeptics in other advanced North European economics.

However, central to this arrangement is the EU with a total GDP of 12.7 trillion euro. As a single market, the European Union makes up the world's largest economy. At the same time, the EU's current strategy is not aimed at the maximum expansion of its borders but rather at establishing a multilevel system of international agreements based on trade norms generated by Brussels. In the final analysis, Switzerland and Norway will have to observe European export standards because the EU remains their main trading partner.

This stratagem is bolstered by the existence of other institutional entities within the European economic structure, i.e. the EUCU and Central European Free Trade Association (CEFTA). The latter is intended as a transitional organization for the countries of the former Yugoslavia and Moldova (previously it operated similarly for East European states) by preparing a normative base and trade rules for their integration into the EU and EUCU. The key specifics of the EUCU are found in the fact that as the EU's trading and economic foundation, it also incorporates Turkey and the mini-states of Monaco, San Marino and Andorra. Turkey's role in this scheme is far from marginal, since the country observes external trade tariffs and the common trade policy (although it remains outside the European Union), is not eligible for subsidies and cannot properly regulate its trade balance since it has minor influence within the European Commission and its trade-and-economic structures. Since 1995, after joining the CU to 2010, Turkey's trade deficit with the EU countries doubled, and grew six times with partners outside the EU. In order to cover the gap, Turkey needs direct investment but its current investment climate is not adequate for its economy and only negatively affects the national currency.

The CEFTA is a key link in the expansion of the common normative base aimed at guaranteeing that the Balkan states will go ahead with reforms related to the movement of goods and services. Notably, the logic of extending European trade norms and rules forms the basis of the Eastern Partnership, an initiative within the EU grand strategy for associations with third-party countries. Thus grand strategy prioritizes not just the European South and East but also the Maghreb and the Middle East. An association differs from stage-by-stage integration, as is the case with the CEFTA, and implies the partial amendment of the domestic normative base as required to intensify trading relations with the European Union, as well as adopt certain administrative and civil reforms normally linked with economic cooperation.

Stumbling Blocks in the EU-EEU Relationship

As far as this transforming space is concerned, neither the CIS Free Trade Area (CIS FTA) nor the Eurasian Economic Union have managed to become the EU's institutional partner in the matters of integration and the harmonization of trade rules and norms. Deep underlying differences between their trading mechanisms are obvious, since the two bodies view the regulation of customs tariffs differently. These disagreements are not exactly irreconcilable, for example, between the EEU and the EFTA, whose trade in 2012 reached 8.6 billion euro. More evidence can be found in the numerous successful bilateral talks and partnership agreements, as well as in the continuing consultations on the free trade area. The EU-CIS FTA format is also free from insurmountable differences. As is in the case of EEU-EFTA cooperation, interaction between the two blocs is not dependent on tariff policies. Russia's membership in the WTO works as an extra obstacle for EEU maneuvering, since diverging legal interpretations between the WTO and the EEU have brought about the situation, by which Russia can be supplied with goods at tariffs lower not only in comparison with Ukraine after its has signed the EU Association Agreement, but also lower than those applied to Kazakhstan and Belarus, its Customs Union partners.

Today, especially with the ongoing Ukraine crisis and the gradual consolidation of international public support for sanctions against Russia, it seems rather difficult even to mention an integrated Greater Europe economy, since there are too many interwoven disagreements generated by the customs norms of the EU, EEU and WTO. In addition, the European Commission from time to time has accused the EEU of protectionism, and not without formal grounds. As a matter of fact, the EU average protective duty runs at 5.5 percent, while the figure for Russia is 10 percent. However, Brussels officials appear to forget that en route to integration in the 1950-1970s, West Europeans experienced a wave of protectionism as well. In actuality, any growing economy tends to strengthen its trade barriers. For example, the protective duty in Turkey stands at 9.6 percent, almost as high as that in Russia. Hence, a simple but noteworthy conclusion: the European Union and the EEU Customs Union view their tariff policies differently due to the structural specifics of their economies, i.e. the advanced liberalized markets in the EU and evolving and more isolated markets in the East.

Bridging the Gaps

Despite the frosty political rhetoric, sanctions and mutual accusations, the European Union cannot but conceal that cooperation with its Greater Europe partners in the East is, first, intrinsic to its energy security, and, second, a must for developing its investments.

As a matter of fact, although the U.S. oil and gas industry lobbies are on the offensive and Europe is keen on green energy, Russian gas is far from replaceable in the long term. A February 2014 Brookings Institution report insisted there is no alternative to the Russian gas in the near future. The U.S.A. and the Middle East are working hard to develop LNG transportation infrastructure but demand in Europe is annually dropping by 5-7 percent due to its much higher price compared to regular natural gas. According to Bloomberg, if Europe switches over to alternative gas supplies, the average cost of gas, now priced at USD 53 billion for current Russian supplies, will double. Moreover, Russia is benefitting from production cuts in Great Britain, the Netherlands, Norway and Algeria. However, the EU is still interested in diversifying its imports, primarily by raising production in the Caspian and laying gas pipes across Turkey, for example within the project of the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (ТАР). To this end, both Russia and Turkey, despite political and cultural differences, are seen by the EU as guarantors of regional energy security. These two countries are not likely to join the European Union in its current format but should become essential to the Greater Europe market space by helping to maintain stability both within the entire European economy and its center, i.e. the advanced Western and Northern European countries.

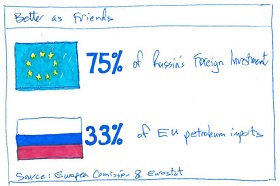

As for the foundation's second component –investment – trends in Europe are extremely divergent. On the one hand, most FDI (60 percent) arrive to the EU from the United States, which is much more significant than Russia or Turkey, for whom the European Union is primarily important as an export market. On the other hand, the EU is important for Russia and Turkey as the primary source of FDI, with Russia receiving 75 percent and Turkey 70 percent of their total take from Europe. The European Union is also interested in expanding the geography of its investments, including the fast growing Eastern markets. However, FDI flows to Russia seem to have reached their limit, while the return investment from Russia into the EU is definitely not capitalizing on opportunities available. The key problem is in the faulty legal base regulating cooperation in investment policies, which are definitely outdated, as eight out of 20 agreements were signed during the Soviet era, 11 more during the first half of the 1990s, and only one signed in the early 2000s. And we should not forget about the harmful, though temporary, consequences of economic sanctions against Russia.

However, the existing grounds for investment cooperation between Russia and the EU, along with engagement in the energy sector, are a solid foundation for further economic integration within Greater Europe. The only problem for attracting major investments is in Russia's lack of a modern legal base. When political tensions over Ukraine subside, Russia should focus on detailed talks over investment agreements, not only between Russia and the EU but also between the EEU and the EU. In contrast to the unlikely and almost certainly futile negotiations on a free trade area with the European Union (although it seems possible in the EEU-EFTA format), an investment agreement between the EEU and the EU could be the first step toward inter-systemic interaction. This is something of interest both for European investors and separate EEU sectors, for example metallurgy and automobile making. Such talks could allow the two sides to concentrate on encouraging and protecting investments and help balance the disagreements related to access to markets of goods and services, which are so far obstructing Russia-EEU-EU cooperation and strengthening the Greater Europe equilibrium. Investor mistrust, political uncertainty in Ukraine and mutual sanctions between the EU and Russia are hurting trade, for in the first six months of 2014 EU exports to Russia dropped by 12 percent and imports by eight percent.

Because of this, as diplomatic efforts on settling the Ukraine crisis are ongoing, it is important to step up discussions on the establishment of investment cooperation and mutual guarantees in the energy sector, which still underpins the trade balance with Europe. In the long run, the EU and the EEU should refrain from escalating tensions and make mutual concessions aimed at reconciling the trade and customs rules of the two unions. The absence of progress in these matters still hampers the advance of Russia-EEU-EU trade and economic cooperation, as well as an upgrading to the Greater Europe symmetry.