South Korea and the Development of Offshore Shipbuilding in the Russian Far East

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Post-graduate student in the Russia in the Asia-Pacific Region: Politics, Economy, Security international educational program at the Far Eastern State University

Expert at the Laboratory of Asia-Pacific International Institutions and Multilateral Cooperation, Far Eastern State University School of Regional and International Studies, Сorrespondent of the Regional News Agency Data

Due to the Russian Federation’s lack of offshore shipbuilding experience and the general shipbuilding crisis, development of the sector in the Russian Far East depends on raising foreign investment and attracting modern technology and international management expertise. The Republic of Korea appears to be the optimal partner for achieving those goals.

Due to the Russian Federation’s lack of offshore shipbuilding experience and the general shipbuilding crisis, development of the sector in the Russian Far East depends on raising foreign investment and attracting modern technology and international management expertise. The Republic of Korea appears to be the optimal partner for achieving those goals.

The case for the development of shipbuilding in the Russian Far East stems from the need to create a modern fleet. Average vessel obsolescence has reached 80% [1]. The fleet has not be upgraded in the past two decades, while intensive operation of the existing fleet is wearing it down at an accelerated pace.

The Far East risks losing this industry unless comprehensive steps are taken to upgrade the existing – and create new – shipbuilding capacity there. The matter has taken on special importance in light of Russian oil and gas companies’ plans to develop offshore deposits of Sakhalin Island, in the Sea of Okhotsk, on the Kamchatka Peninsula and in the Arctic Ocean seas [2], an undertaking that requires supply vessels and gas tankers, as well as maritime equipment and oil and gas production platforms. It is worth noting that offshore shipbuilding is a new industrial production area for Russia and, as such, its development requires a focused government and corporate policy as well as considerable investment. Based on the need to create a new fleet and offshore infrastructure, as well as to develop civilian shipbuilding in the Far East, the decision has been made to expand the capacity of the Zvezda shipyard at Bolshoy Kamenin the Maritime Territory. Essentially, the project involves the construction of a new shipyard that would technologically best any of Russia’s existing shipbuilding facilities. Cooperation with international partners is a prerequisite for carrying out a project of such a magnitude, because the situation in R&D and industrial management in Russia is far from perfect [3].

Cooperation of Russian Companies with DSME

That is why the first stage of the Zvezda-DSME project in 2009 involved the establishment of a joint venture between the United Shipbuilding Corporation (USC) and Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering Co., Ltd (DSME), but the Korean company withdrew from the project in 2012, citing the uncertainty surrounding financing from the Russian side [4].

As a result of the failure to meet the shipyard’s completion deadline, USC was forced to sell 75% less two shares in its subsidiary OAO Far East Shipbuilding and Ship Repair Center to a consortium of Gazprombank and Rosneft at the end of 2013 [1]. Vladimir Putin announced the decision at a meeting on the outlook for the development of civilian shipbuilding at Vladivostok in August 2013 [2]. The close attention paid to the project by Russian leadership is a testament to its political importance, while the involvement of Russian oil and gas corporations has reiterated the project’s focus on offshore development.

As part of Vladimir Putin’s official visit to South Korea in November 2013, Rosneft, Gazprombank, Sovcomflot and DSME signed a memorandum of understanding on cooperation in establishing a shipbuilding cluster in the Far East. The parties agreed to jointly complete the new Zvezda shipyard and establish a joint maritime engineering centre to develop equipment for offshore projects, and also set forth key conditions for technology exchange, production localization, and order placement [6].

At the end of 2013, after Vladimir Putin’s visit to Seoul, the possibility of acquisition by Rosneft, in consortium with Gazprombank and Sovcomflot, of 31.5% of shares in DSME owned by the Korea Development Bank (KDB) as part of privatization has been actively discussed i. The value of the deal is estimated at USD 0.9–1.9 billion [7]. It can be viewed as aimed at both technological cooperation and transfer of complex orders to Korean shipbuilders in case of a failure by the Russian side to complete them on time.

Offshore shipbuilding is a new industrial production area for Russia and, as such, its development requires a focused government and corporate policy as well as considerable investment.

South Korean experts have noted that an acquisition by the Russian Federation of such a large stake in a shipbuilding company would provide it with full rights to take part in making management decisions. Yet DSME, which, besides large-tonnage civilian vessels, also manufactures submarines, patrol and other types of naval ships, is a defence contractor and as such, under Korean law, an acquisition by a foreign company of than a 10% in it needs to be approved by the government of South Korea. It is Seoul’s position at present that local business should own and manage DSME [8].

In this regard, Korean experts are predicting inevitable competition among the Republic of Korea’s large finance and industrial groups for the company’s assets going forward. At the same time, a continuing downturn in the shipbuilding industry makes it very likely that even such industrial conglomerates as Hanhwa Group, POSCO, or GSGroup ii, which have expressed interest in purchasing DSME assets, would be unable to turn the situation around, and selling a large equity stake in the company would take a long time.

For example, in November 2008 the Hanhwa chaebol bid for DSME iii, expressing readiness to invest around USD 6 billion in the company. But the financial crisis had already broken out, and in January of the following year the company withdrew its bid and announced a complete halt to negotiations on the acquisition of the shipbuilding enterprise 9.

The Current State of Shipbuilding in the Republic of Korea and Seoul’s Interest in Cooperating with the Russian Federation

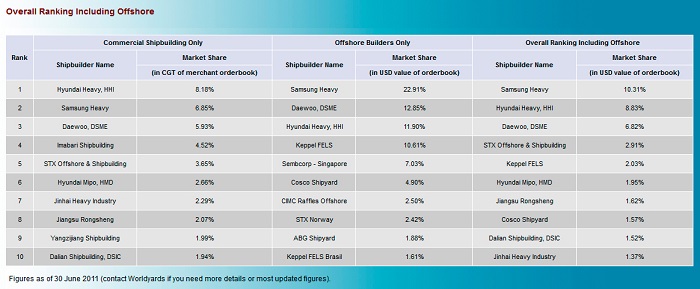

With 30%, the Republic of Korea holds the second largest share of the global shipbuilding market after China, which manufactures 45% of all vessels (by register tonnage), followed by Japan, which has 18% of the global market [10]; the rest of the world lags far behind the top three. The Republic of Korea’s shipbuilding industry benefits from high productivity, technological superiority, production automation and efficient management. Hyundai Heavy Industries, Samsung Heavy Industries, DSME and STX Offshore & Shipbuilding are drivers of global shipbuilding. As global competition intensifies, Korea is focusing on building large and technologically advanced vessels and maritime equipment with high added value, which accelerates the technological development of the industry [11].

At the same time, the current situation in the Republic of Korea’s shipbuilding industry is seen as not quite favourable. The total amount of orders for new vessels received by South Korea in 2012 was 199 units, which allowed just a 59% utilization of existing capacity [12]. This has dealt a substantial blow to small and medium enterprises supplying components and equipment, and to subcontractors of large shipbuilding companies such as DSME. The Republic of Korea views the joint project for building the Zvezda-DSME shipyard as one of the best opportunities to improve its own business environment in the industry by South Korean firms that manufacture components and vessel equipment penetrating Russia’s Far East and staying there, thanks to an almost total lack of modern shipbuilding or machine building facilities in the region.

Thus, one of the main characteristics of the Republic of Korea’s approach to the development of bilateral cooperation with the Russian Federation in the area of shipbuilding will be lobbying for the interests of South Korea’s businesses involved in this sphere, something that will take the shape of “pushing” relevant products manufactured in the Republic of Korea to the Russian market while trying to secure special, preferential treatment for them.

The specific scale of Russian–Korean cooperation has not yet been determined; however, as part of fulfilling its partner obligations, DSME is prepared to assist at the initial stage with the shipyard upgrade and expansion of its production capabilities by developing and making available design, production technology and proprietary know-how of the facility’s building and management and production process organization [14]. Due to the excessive backwardness of Russia’s shipbuilding industry, the focus should be on obtaining basic technology required for setting up and optimizing production facilities, rather than on cutting-edge technology.

With 30%, the Republic of Korea holds the second largest share of the global shipbuilding market after China, which manufactures 45% of all vessels (by register tonnage), followed by Japan.

At the same time, according to comments from DSME employees, transferring forward-looking and innovative vessel design technology to Russia in the nearest future is out of the question – and this is exactly what, in the opinion of the Republic of Korea, the Rosneft led Russian consortium is interested in above anything else. Korea is aware that Moscow’s ultimate goal is to become capable of manufacturing complex types of large-tonnage vessels on its own, and is worried about the emergence of a rival, even if only a potential rival, in the market [15].

In its turn, the South Korean side considers obtaining firm guarantees from the Russian Federation that the Zvezda-DSME shipyard would have the right of first refusal to take orders for large-tonnage vessels and offshore structures from Russian third parties as a prerequisite for “effective bilateral cooperation”. What’s more, the Republic of Korea’s shipbuilders insist on additional agreements under which Russia would send to the Republic of Korea any contracts that exceed the capacity of the shipyard at Bolshoy Kamen [16].

A certain openness of the Republic of Korea to the idea of transferring its own technology is explained by the fact that Seoul considers such projects as an opportunity to get access to Russian oil and gas projects, through which the Republic of Korea would be able to secure a better deal on hydrocarbon supplies. This would have a positive effect on the diversification of supplies and the country’s energy security. Now that the shipyard at Bolshoy Kamen has become an asset owned by Russian oil and gas companies, the Korean side will continue working in that area.

Dong-min Jin:

South Korea is Driven to the Arctic by National

Pride and Business Opportunities

Besides, South Korea is interested in developing the Arctic and utilizing the logistic potential of the Northern Sea Route. Seoul is planning to expand scientific research in the Arctic and increase its activity there through its Arctic scientific research stations. For example, the government of the Republic of Korea is seeking to sign a memorandum of understanding with Russia establishing a joint port in the Arctic Ocean [17]. In May 2013, Korea obtained the status of an observer at the Arctic Council.

Problems of Russian Shipbuilding and the Russian Federation’s Interest in Cooperation with South Korea

Shipbuilding in the Russian Far East is characterized by a lack of modern shipyards and obsolete fixed assets. Technological backwardness is evident in vessels being built to designs from the 1960s and 1970s. The industry’s development in the region also suffers from problems with workforce. Because of the shortage of specialized educational institutions and the substandard quality of training, shipbuilding companies are forced to employ foreigners, in particular from Ukraine, where the Soviet Union’s main shipbuilding capacity was concentrated, as well as from China and even from North Korea.

Engineers are trained using outdated curricula and without paying due attention to modern technologies and CAD tools, which is holding the national shipbuilding back [18].

The market’s development is also hamstrung by its immaturity and management problems, since most of the region’s shipbuilding companies were founded from Soviet enterprises, and many have inherited a bloated and inefficient management. It is worth noting that, even in the Soviet era, the Far East lacked shipyards equipped for large-tonnage shipbuilding, which only amplifies the challenge of establishing a large-tonnage shipbuilding centre there.

A certain openness of the Republic of Korea to the idea of transferring its own technology is explained by the fact that Seoul considers such projects as an opportunity to get access to Russian oil and gas projects.

With that in mind, cooperation with the Republic of Korea on shipbuilding could be an interesting proposition for Russia for a whole number of reasons.

First of all, cooperation on technology is of paramount importance. Korea’s technologies for vessel hull welding and assembly are of particular interest. Korean equipment could be of use to outfit Russian vessels. South Korean project solutions could be used in Russia to reduce shipbuilding costs. The Republic of Korea is a global leader in offshore infrastructure building; for instance, modular technological structures for platforms operating off Sakhalin’s shore were made in the Republic of Korea.

Secondly, joint projects envisaging work sharing between Korea and Russia should help streamline product completion timetables and technological processes, as well as reduce customs clearing costs.

Thirdly, Korean production organization and project management expertise is in demand at Russian shipyards. It’s worth pointing out the opportunities for streamlining purchasing, logistics and production processes, and marketing on the Korean model. Processes computerization and automation represent a competitive advantage of shipbuilding in the Republic of Korea. Labour productivity in the Republic of Korea is triple the projected indicator for the Zvezda shipyard, and approximately 18 times the productivity of existing Russian shipyards [19]. South Korea is a global leader in environmental protection and industrial safety, while the manufacturing quality of South Korean shipbuilding meets the strictest international standards. Training Russian specialists at South Korean shipyards and educational institutions of the Republic of Korea should have a positive effect on implementing Korean expertise at Russian enterprises.

***

Russian–Korean cooperation on shipbuilding is a necessary success factor for the Russian Federation’s plans to create a tanker fleet and infrastructure in order to develop offshore deposits in the Far East and the Arctic. Specialized vessels and maritime structures will increase Russia’s chances for the efficient development of promising deposits on the Russian shelf, and guarantee steady hydrocarbon production volumes. Besides, the development of shipbuilding will have a positive effect on economic growth in Russia’s Far East region.

Russia’s offshore activity will also reflect positively on Russia’s status as a great sea power and dispel any doubts concerning its ability to develop its offshore zones on its own.

Effective Russian–Korean cooperation in this industry will help Moscow and Seoul strengthen their positions in the Arctic, which is bound to cause resentment among other Arctic Council member countries. In particular, the United States and Canada will do their best to thwart the expansion of Russia’s influence in the region. It is unlikely that the Republic of Korea, one of Washington’s key military and political allies in Asia-Pacific, will yield to American pressure here, because otherwise it would be simply cut off from the process of developing the Arctic. Among all Arctic-facing nations, it is Russia that Seoul views as the most fitting partner capable of providing it access to the Arctic’s raw material and transport and logistic resources.

Korea’s participation in bilateral cooperation with the Russian Federation in shipbuilding could displease China and Japan, which, like the Republic of Korea, enjoy observer status at the Arctic Council and view each other as direct competitors in penetrating the Arctic. That is why potential attempts by Beijing and Tokyo to hinder the strengthening of Russian–Korean cooperation cannot be excluded. China and Japan are likely to offer their own technological support to substitute for the Korean one.

Interest in strengthening the partnership between our two countries on the political level should also be taken into account. Given the specifics of both Russia’s and South Korea’s foreign policy, as well as the foreign trade decision-making processes, important arrangements are being discussed at the level of heads of state, resulting in increased attention from the countries’ leadership, and special strategic importance being attached to those arrangements. Thus, amid the current foreign political situation, the Republic of Korea is Russia’s most promising partner for technological and investment cooperation in the Far East.

At the same time, it should be noted that after several large bilateral projects in the Far East went awry, including the Zvezda-DSME shipyard and the Hyundai Electrosystems electrical equipment plant, which both failed to materialize through the fault of the Russian side, Korean investors have become less inclined to see the outlook for further cooperation in positive light and are no longer prepared to face similar risks for any new projects. The Republic of Korea is demanding unconditional guarantees that financing of joint projects will be forthcoming from the Russian side, and that future sales of output will be ensured.

i. The government holds a 44.83% equity interest in DSME, including 31.46% through KDB, 12.15% through the Financial Supervisory Service, and 1.22% through the Treasury Fund. The remaining 55.17% is privately owned, including foreigners.

ii. Hanhwa Group, founded in 1952,isone of South Korea’s largest investment and industrial conglomerates (chaebols).

POSCO is a leading Korean metals corporation, the world’s second largest steel producer by market value. It was founded in 1968. GSGroup is a South Korean chaebol founded in 2004after separating from LG.iii. Chaebol is a form of financial and industrial group in South Korea, a conglomerate consisting of a number of formally independent family-owned businesses under single administrative and financial control.

1. Russia’s civilian shipbuilding market analysis // DISCOVERY Research Group marketing research agency.11 February2014. [Web resource]. URL: http://www.drgroup.ru/436-analiz-rinka-grajdanskogo-sudostroeniya-v-rossii.html (in Russian).

2. Minutes of the meeting on the outlook for the development of national shipbuilding // Russian President’s website. 30 August 2013. [Web resource]. URL: http://news.kremlin.ru/news/19107 (in Russian).

3. L.E. Kozlov, D.A. Reutov. Foreign policy context of cooperation between Russia and the Republic of Korea on industrial modernization of the Far East // Oikumena. Region Studies: a scientific and theoretical journal. – 2012. – No. 1 (20). – p. 25-33.

4. The Zvezda-DSME shipyard loses foreign investor // Russian Shipbuilding Portal. 2012, 7 September. [Web resource]. URL: http://shipbuilding.ru/rus/news/russian/2012/09/07/zvezda_dsme_money_070912/ (in Russian).

5. O. Klimenko. Far Eastern super shipyard turns into a JV //Far East Capital. 20 November 2013. [Web resource]. URL: http://dvkapital.ru/companies/primorskij-kraj_20.11.2013_5702_dalnevostochnaja-superverf-ushla-v-sp.html (in Russian).

6. Rosneft, Gazprombank, Sovkomflot and DSME agree on a joint project to develop an engineering and shipbuilding cluster in Russia’s Far East // Rosneft.13 November 2013. [Web resource]. URL: http://www.rosneft.ru/news/pressrelease/13112013.html (in Russian).

7. K. Melnikov, E. Popov. Rosneft to enter Korean shipyards // Kommersant. 2013, 14 November. [Web resource]. URL: http://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2342642 (in Russian).

8. Government: DSME won’t be sold abroad, 정부외국에대우조선안판다 // KBS World news portal. 10 December 2013. [Web resource]. URL: http://world.kbs.co.kr/korean/news/news_Po_detail.htm?No=204241 (in Korean).

9. Ibid.

10. The shipbuilding market: Annual review 2013 // Barry Rogliano Salles. [Web resource]. URL: http://www.brs-paris.com/annual/annual-2013/pdf/02-newbuilding-a.pdf

11. K. Bogdanov. Korean shipbuilding: Running on a treadmill // RIAC. 10 December 2013. [Web resource]. URL: /en/inner/?id_4=2824#top

12. Korea forecasts increased interest in shipbuilding // RIA Fishnews.ru. 28 December 2012. [Web resource]. URL: http://fishnews.ru/news/20250 (in Russian).

13. Russian Zvezda shipyard extends a hand to Korean business again? 러시아즈베즈다조선소, 한국기업에다시손내미나? // Global Window web portal. 2013, 5 November. [Web resource]. URL: http://www.globalwindow.org/gw/overmarket/GWOMAL020M.html?BBS_ID=10&MENU_CD=M10103&UPPER_MENU_CD=M10102&MENU_STEP=3&ARTICLE_ID=5007841&ARTICLE_SE=20302 (in Korean).

14. STX Shipbuilding’s penetration in Russia a soap bubble… Vessel orders cancelled. Russian shipyard building project passes to DSME…, STX조선, '러시아진출' 물거품…선박수주도취소; 러시아조선소건설프로젝트대우조선손에… // Morning Today news portal. 26 November 2013. [Web resource]. URL: http://www.mt.co.kr/view/mtview.php?type=1&no=2013112514195835033&outlink=1 (in Korean).

15. DSME to make Russia’s dream of an advanced shipyard come true, 러시아초대형조선소꿈, 대우조선해양이이뤄준다 // Korea Economic Daily news portal. 18 November 2013. [Web resource]. URL: http://www.hankyung.com/news/app/newsview.php?aid=2013111812521&sid=&nid=&type=0 (in Korean).

16. DSME to take part in Russian shipyard upgrading consortium, 대우조선, 러시아 '조선소현대화' 컨소시엄에참여 // Newsis news portal. 19 November 2013. [Web resource]. URL: http://www.newsis.com/ar_detail/view.html?ar_id=NISX20131119_0012524348&cID=10101&pID=10100 (in Korean).

17. South Korea intends to strengthen presence in the Arctic // Arktika-info.1 August 2013. [Web resource]. URL: http://www.arctic-info.ru/News/Page/ujnaa-korea-namerena-ykrepit_-prisytstvie-v-arktike (in Russian).

18. V.V. Veselkov. Particularities of training shipbuilding technology staff // GlavSprav. Education. Science and methodology section. 17 May 2012. [Web source]. URL: http://edu.glavsprav.ru/msk/nmr/mppo/479/ (in Russian).

19. A. Kazakov. Shipyard of discord – Part I // Military-Industrial Courier. 9 November 2011. [Web resource]. URL: http://vpk-news.ru/articles/8334 (in Russian).

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |