Interview

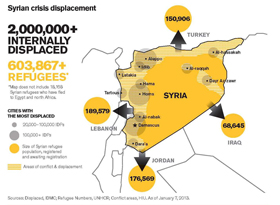

Reports from Syria show no sign of improvement of the situation there. According to the United Nations over 70,000 people have perished, at least 2 million people have been displaced, about 1 million have fled to neighboring countries as a result of the conflict that broke out nearly two years ago. The international community has procrastinated with stopping the bloodshed while Syria has been laid to waste. Mark N. Katz shares his perspective on the recent developments in the country.

Interview

Reports from Syria show no sign of improvement of the situation there. According to the United Nations over 70,000 people have perished, at least 2 million people have been displaced, about 1 million have fled to neighboring countries as a result of the conflict that broke out nearly two years ago.

The international community has procrastinated with stopping the bloodshed while Syria has been laid to waste.

Mark N. Katz - George Mason University professor and Middle East Policy Council senior fellow who specializes on Russian foreign policy toward the Middle East - shares his perspective on the recent developments in the country. He comments on the resignation of Syrian opposition’s leader, Russia’s possible role in the “new” Syria and the shift in the international community’s attitude towards the crisis.

Interviewee: Mark Katz, Professor of Government and Politics at George Mason University, Senior Fellow at the Middle East Policy Council

Interviewer: Maria Prosviryakova, Russian International Affairs Council

Recently the leader of the opposition Syrian National Coalition Ahmed Moaz al-Khatib announced his resignation. He said he could only improve the situation by working outside of the coalition. What do you think influenced his decision?

I think that these kinds of coalitions are inherently fragile. This is typical of opposition movements that they splinter over policy differences, over personality differences. And, of course, there had been a lot of criticism because Ahmed Moaz Al-Khatib was willing to talk with elements of the Assad government and this was too much for some of the opposition groups.

So, now the Syrian opposition has a new prime minister, Ghassan Hitto, and what will be his responsibilities vis-à-vis the president? On the other hand, Al Khatib was seen at that recent Arab League meeting despite his resignation.

Why, then, did he resign? I think that in many respects it was out of petulance. In other words, it is like: - “I am leaving”. -“Oh, no, no. Come back! Come back!” It seems that this is sort of what has happened. They haven’t accepted his resignation. So, it is not completely over yet. I am not sure how serious this really is.

And what could his plan be?

Like a lot of these people, Ahmed Moaz Al-Khatib may think that he is just so valuable to the movement, that it will, of course, do whatever he wants so that he would come back, and maybe the Syrian opposition really will.

Ahmed Moaz al-Khatib was seen as a great hope for Syria’s opposition. What might his resignation mean for the opposition forces?

They may eventually find somebody else. I think that the trouble with the movements like this it is that the external leadership always has more of the world’s attention than the internal leadership. But the internal leadership in fact has more control. As the opposition forces come stronger, as they become closer to coming to power, then the splits are more likely to take place. So, this is not an unusual development.

The future of Syria raises international concerns. Particularly, because Syria is becoming a haven for extremists. The al-Qaeda-linked Jabhat al-Nusra doubled size in Syria. How do you believe the international community can secure that a credible opposition, not jihadists, will take over the country?

The problem is that they can’t, can they? What occurred in Egypt and Tunisia was very quick. Even the moderate Islamists didn’t need the radicals to come to power: they do not want to be dependent on them either. Now, with the situation that we have in Syria it is very likely that the radicals are going to play an important role there. The question now is whether they overplay their hand – radicals usually do. The longer the conflict lasts, though, the stronger the radicals usually become.

I do not think that the international community can do all that much. Inevitably, whoever comes to power, there will be those who want revolutionary purity and there will be those who are more pragmatic and want to do business with the rest of the world. All we can do is to try to work with more moderate elements among the radicals (if, of course, there are any). Also, whenever we start imposing sanctions we should remember that this will just play into the hands of the radicals. Down the road they may become tamer, but it will be a long time before they do.

The international community has procrastinated with taking a united and effective decision while Syria has been laid to waste. Nevertheless, now there is a growing international consensus that more should be done to support moderate opposition. The mood appears to be shifting in Washington; the UK and France have been vocal in their hopes of arming rebel forces. What can be and should be done at this point by the international community to stop the bloodshed?

It very much resembles Afghanistan in the 1980-s. The West allowed Pakistan and Saudi Arabia basically to take the lead. We supported their efforts. That is what happened here as well. Saudi Arabia, Qatar – they are motivated: they want to get rid of an Iranian ally. The Obama administration in particular has been diffident - they do not know what they want. It has made the worst kind of compromise: the Obama people do not want to go in all the way, but they do not want to do nothing. So, they kind of do a little bit. What does that mean? It is not a policy of a great power. It is those countries that are the most actively involved that have the best chance of affecting the outcome.

I think that the Saudis and the Qataris do not really want radicals to come to power, and they hope that such people will be dependent on them and so do what Riyadh and Doha want. But there is no gratitude in international relations, is there? When you give people arms, you give them the means to be independent. So, they do not have to follow your orders once they come to power.

A week ago the Syrian opposition attacked the website of the Kremlin's envoy to the Far East and urged "all Russian people to halt weapon deliveries to president Bashar Assad's forces”. Otherwise, the message's authors threatened, Russia would not get any preference in the "new Syria." What can Russia count on in the “new Syria”, if the opposition finally comes to power? Will Russia have almost no influence in the region then?

If you look at what has happened in Libya, this shows a path. In other words, the same thing happened with the Libyan opposition. They used to say that the Russians were terrible and they would suffer. But yet we now see one of the Libyan leaders has just been to Moscow. And then it appears that Moscow is now training Libyan solders. Moscow is now talking about resuming arms sales to Libya. Russians petroleum firms, Tatneft in particular, are going back into Libya. In fact, Russia seems to be doing quite well there now.

The same thing can be said about Iraq. They used to say that Saddam Hussein was Moscow’s ally and that Russia lost out in Iraq after he was overthrown. Yet, if anyone has benefited from what happened in Iraq it appears to be Russia. It is Russia that just signed a $4.5 billion arms contract with Iraq. Also, it is Lukoil –and other Russian firms - that are operating in the southern part of Iraq.

I think that the same thing will happen with Syria. Initially, of course, the new Syrian regime will be very angry with Moscow. One thing that Russia can count on, though, is that there will be differences between whoever rules Syria and America and the West. And that will be Russia’s opportunity to take advantage of. And I think Russia will.