Global migration processes can be divided into roughly two main models, the Mexico-U.S.A. system in the Western hemisphere and the Russia-CIS system in Eurasia. Although Russia is predominantly a recipient of migrants and Mexico is a donor, there are enough similarities to allow for comparisons of the overall migration dynamics and regulatory practices of the two countries.

Growth in migration has become a key characteristic of the modern international environment, which has resulted in the creation of two systems of migratory flows between borderline countries, the Mexico-U.S.A. system and the Russia-CIS system [1]. Both key players in the total global figures of migration, these systems related to these two countries differ: Russia is a migrant recipient while Mexico is a migrant provider. However, the borderline migration model has also both similarities (a lengthy frontier between donor and recipient countries) and differences (demographic processes, living standards and quality of life, and employment patterns) that allow us to compare and analyze the migration dynamics regulatory practices in Mexico and Russia. While Mexico-U.S.A. migratory flows dominate the Western Hemisphere, ties between Russia and the CIS significantly affect the socio-economic environment in Eurasia. The scale of the two systems is clearly seen from the fact that in 2010, the United States was the world leader in the number of immigrants, i.e. 42.813 million according to the World Bank data, while Russia was second with 12.270 million.

Two Migration Systems: Similarities and Differences

The Mexico-U.S.A. system is quite helpful for accurately understanding similar processes in Russia. Migration from Mexico to the United States skyrocketed in the 1970s, while inflows into Russia stepped up in the 1990s and 2010s. The differences in timing allow us to use Mexico as a case study to analyze possible scenarios for the future of the migration in Russia.

Mexican migrants arriving in the U.S.A. make up one of the world's most numerous groups on the move in the world, with Mexico being the global leader among donor countries and the third largest recipient of remittances, trailing behind only India and China. By 2010, Mexico had 11.9 million (in absolute figures) citizens living outside its borders, i.e. 10.2 percent of its population [2], and 98.1 percent of them residing on U.S. territory (1, 2).

The increase in Mexico-to-the U.S.A. migration coincided with significant population growth in Mexico from the 1960s to the 1990s. As of late, the population increase has slowed down considerably – from a rate of 32.2 per 1,000 population a year from 1955 to 1960 to 10.8 by 2010. The birthrate has also fallen from 46.8 per 1,000 population in the period of 1955-1960 to 17.3 in 2010. This trend is reflected in the cumulative birthrate, i.e. respectively 6.8 and 2.1. For comparison, the birthrate in the United States reached 5.5 per 1,000 population [3] in 2009.

In Russia, the 2011 natality figure was 0.9, while trends in most CIS countries were exactly the opposite – 20.6 per 1,000 population in Kyrgyzstan, 25.0 in Tajikistan, 18.7 in Uzbekistan, and 13.8 in Kazakhstan [4]. And in contrast to the downward Mexican tendency, the demographic situation in Central Asian republics still holds.

Facing snowballing migration flows from Mexico, in the mid-1980s, the U.S. had to reform its federal legislation and legalize Mexican and other migrants, the broadest initiative being the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act which legitimated the stays thousands of migrants but still failed to restrict the stream of wetbacks. Since 1986, there have been numerous although less far-reaching attempts to restrict illegal migration, among them tougher punishments for employers hiring illegal migrants, restricted access to welfare benefits, and simpler deportation procedures at the state level. Quite symbolic was the construction of a wall launched in 2005 along lengthy stretches of the Mexican-American border. In 2013, the Obama administration initiated a new immigration reform so that illegal foreigners could legalize their status in the U.S.

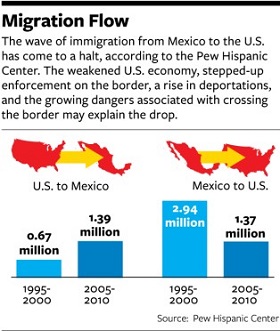

As a matter of fact, these steps were predominantly unilateral, with no decisive effect either on the policies of the southern neighbor or the numbers of the arriving Mexican migrants. However, in 2011, the Pew Hispanic Center found that the net increase in migration from Mexico ceased for the first time since the Great Depression and following four decades of intensive growth. This meant that the number of immigrants leaving or deported from the United States was equal to the number of arrivals.

This turning point occurred due to major changes in the economic and socio-political life of the United States and Mexico, primarily caused by negative trends in the U.S. labor market related to rising unemployment stemming from the global financial and economic crisis, as well as from stricter controls placed on the U.S.-Mexico border. Also of importance seems to have been the gradually growing prosperity of the Mexican population and the indirect effect of the demographic changes driving the intensity of the exit factors.

Socio-Economic Impact: Migrants' Remittances

Money transfers are a key economic component of migration, which shape both family welfare and the growth of municipal entities, as well as play a role in government policies. Once sufficiently accumulated, remittances can help drive the development of small enterprises and other private initiatives. At the macro level, they also have an effect on the current account balance and are part of the calculation of national GDP [5].

Mexico is a world leader among recipients of remittances, having received USD 26.06 billion in 2007. Despite overall decline due to the global crisis, in 2012 Mexico received USD 22.45 billion, only counting the economic contribution of migrants to the development of their country of origin. In Mexico, the share of GDP due to money transfers was 2.1 percent, whereas in countries with less diversified economies, this figure is much higher. For Mexico, this type of revenue can hardly be overestimated, as it competes on the level of the oil sector and tourism.

The migration model in question places the more developed country as the source of remittances, as is the case of the United States vis-à-vis Mexico and Russia vis-à-vis the CIS. In 2012, Russia accounted for 57.9% of remittances received in CIS countries, while the share of the destination country income made up 72.2 percent for Kazakhstan, 72.2 percent for Kyrgyzstan, 57.7 percent for Tajikistan, 62.4 percent for Azerbaijan, and 55.8 percent for Ukraine.

These figures only highlight the close socio-economic links between Russia and the CIS, as well as the vulnerability of certain economies to negative financial and economic processes caused by Russia’s economic slowdown.

The tight dependence of economies on this type of revenue is indirectly reflected on the migration policies of these countries. In the Mexico-U.S.A. migration model, the regulatory function belongs to the United States, whereas in the Russia-CIS linkage, it is Moscow which assumes control over migration processes.

Model in Transformation: New Elements Emerge

As an active participant in global migration processes, Mexico is not only sending huge masses of its citizens to the north but also receiving thousands of seasonal workers from such less advanced countries to the south as Guatemala and Belize, in fact reproducing the above model but instead as a migration recipient and not as a donor.

Although the stream is much thinner than the one oriented to the north, it does push Mexico to adopt targeted measures to strengthen its southern border, especially as there is a need to control illegal migration from Central and South America into the United States, as well as to participate in the interdiction of drugs and arms trafficking.

Beginning in the 1990s, the Mexican government has been consistently building a system of border controls, inter alia through the program Forma Migratoria de Visitante Agrícola (Visiting Agricultural Worker Migration Form) which has allowed migrants from Guatemala to obtain temporary farming jobs in the state of Chiapas (1997). From 2001-2003, the Mexican government implemented the Plan Sur (Southern Border) program designed to modernize the border posts for the identification, detainment and repatriation of migrants from Central America who illegally crossed Mexico’s southern border. In 2004, the Instituto Nacional de Migración (National Migration Institute) led a project to launch the Sistema Integral de Operación Migratoria (Integral Migration Action System) that presented an upgraded computerized system for controlling migration streams and repatriation, residence permits, citizenship requests and migration formalities. In 2005, it was incorporated into the National Security System – Plan of Integral Migration Policy at the Mexican Southern Border [6]. In 2009, Mexico introduced the Forma Migratoria de Visitante Local (Local Visitor’s Migration Form) which allowed residents of Guatemalan border territories to visit adjacent Mexican states. On the one hand, these programs strengthened Mexico’s southern border and improved the regulation of labor migration, while on the other, they made it easier for residents of border areas to maintain family ties, since the vast territory is divided by the frontiers but inhabited by people with common history and traditions dating back to the Mayan period.

In the early 21st century, Mexico began to gradually transform its expansive migration model, caused to a great extent by accelerating processes of integration in the region. Although the North American Free Trade Agreement has failed to provide free movement of people between its member countries, as is the case of the European Union, Mexico is receiving many more immigrants. In 2010, their number reached 960,000, with 77 percent of them coming from the U.S.A. [7]. Many are elderly pensioners, though the number of employable persons is also quite high. This phenomenon is very new since Mexico had been a country of mass emigration throughout its entire history.

Notably, the structure of Mexico's migration process in the 1980s differs fundamentally from that of today in large part due to economic growth, higher living standards, slowing population growth, and lower intensity of the exit factors. The exponential rise of Mexican migration has definitely stopped, which makes it possible to single out key elements potentially relevant to migration within the CIS.

Russia and Mexico are countries for which migration has become a major component of socio-economic development, as well as a driver of domestic and occasionally foreign policies. Mexico's example proves that over the long run, changing socio-economic and demographic parameters can give rise to transformations in migration patterns and the alleviation of the exit factors, which sometimes attract more immigrants. Nevertheless, the Russia-CIS system is still characterized by growing migration into Russia, which is not going to change in the near future if current birthrates and living standards in neighboring countries remain as before.

Migration is a significant indicator of processes underway in society, primarily in the labor market. With strong implications for the overall demographic situation, migration can compensate for natural population losses, but cannot stimulate development if it rests on seasonal employment and unskilled labor. It is only higher mobility of skilled workers within the emerging integration spaces and the revitalization of internal migration processes that can give new momentum to a country's socio-economic development.

1. As far as migration is concerned, Russia interacts with Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan) across the lengthy Russia-Kazakhstan frontier. Due to the absence of a visa regime, these countries can be included in the generalized group of those participating in migration of this type.

2. In 2012, the population of Mexico was 114.8 million.

3. Russian Demography Yearbook – 2012. Мoscow: Rosstat, 2012. P. 6 (http://www.gks.ru/wps/wcm/connect/rosstat_main/rosstat/ru/statistics/publications/

catalog/doc_1137674209312).

4. Ibid. P.5; Russian Demography Yearbook – 2000. Collected Statistics. Moscow: Rosstat, 2000.

5. Kudeyarova. N.Yu. Migrants' Remittances and Changes in the Socio-Economic Situation in the Western Hemisphere // Latin America. 2010. Issue 7. Pp. 53–66.

6. Anguiano Téllez M.E. Las políticas de control de fronteras en el norte y sur de México // Migraciones y fronteras. Nuevos contornos para la movilidad internacional/. Barcelona: CIDOB, 2010. P. 170–178.

7. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Estimaciones con base en la Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo, 2012 (http://www.inegi.org.mx/).