Migration in Modern Russia

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 2, rating: 3) |

(2 votes) |

PhD in Geography, Head of the laboratory, RAS Institute of Economic Forecasting

By the 2000s the complex initial phase of transformations brought about by the collapse of the Soviet Union and accompanied by dire economic depression, protracted armed conflicts, and corrosion of established life views, had already passed. The comprehensive state crisis also provoked a severe crisis in migration. Traditional factors shaping migration, such as urbanization, labor markets, education systems and the demographic situation, had long lost their former importance.

By the 2000s, which this reader on migration processes in post-Soviet Russia focus upon, the complex initial phase of transformations brought about by the collapse of the Soviet Union and accompanied by dire economic depression, protracted armed conflicts, and corrosion of established life views, had already passed. The comprehensive state crisis also provoked a severe crisis in migration. Traditional factors shaping migration, such as urbanization, labor markets, education systems and the demographic situation, had long lost their former importance. Other factors such as ethnic discrimination, affecting Russians more than others, the loss of established social identities, armed conflicts, unemployment, and poverty came to the fore. These factors dramatically changed the nature of migration, making it forced in nature, and triggered massive flows of refugees and repatriates bound for Russia. Ethnic delimitation intensified family reunification, while the type of resettlement specific to a period of stable social development and brought about by job training, military service, labor mobility, as well as upward mobility, rapidly declined. The majority of people who moved out of all post-Soviet countries rushed towards Russia, which during the first decade following the collapse of the Soviet Union became a home for forced migrants, regardless of their nationality.

Russia lost no time in responding to this critical situation. Despite the economic difficulties faced by the country, it established the Federal Migration Service (FMS) by the middle of 1992, acceded to the UN 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, and passed laws On Refugees and On Displaced Persons with an accompanying program to help them. As a result, Russia played host to 1.8 million people with refugee status and other internally displaced persons, and to at least as many people without such statuses.

Russia had a positive balance of migration exchange with all of the former Soviet republics, receiving apart from Russians and other ethnic nationalities of the Russian Federation returning to their homeland, about 1 million migrants from the titular ethnic groups of the CIS and Baltic countries [1].

Internal migrations changed radically too. In a matter of years, the mobility of Russians dropped by half, with many people choosing to stay at home during difficult and dangerous times. Recent settlers in the North and the Far East moved in large numbers back home. The direction of internal migrations changed form the north and east to the diametrically opposite center and southwest of the country. For the first time since the settlement of the Far East by the Russian Empire, the former began to lose population. The country was clearly divided into the donor northeast zone and the recipient central-south-western zone. This division is still there 20 years later.

Rural-urban migration faced a reversal as well: in the early 1990s, migration went back from the city to the countryside. The normal trend quickly recovered, but urbanization continued to stagnate throughout the 1990s due to the considerable flow of repatriates to the countryside.

From the very beginning, these destructive processes were offset by new opportunities offered by Russia’s and other CIS countries’ adoption of the open door policy and economic market reforms. The development of private enterprise in Russia inspired the emergence of significant employment and wage opportunities, new alternatives to the ailing state sector of the economy. This paved the way for snowballing shuttle trade migration that operated to buy and resell Polish, Turkish, Chinese, etc. goods.

In those days of economic devastation, such shuttle trips were literally a lifeline for people. At the end of the 1990s, the number of Russians involved mostly in shuttle labor migration was estimated at about 5 million people, out of which 1.5-2 million left the CIS for trade tours, while about 3 million people found employment inside Russia itself [2].

As the overall situation stabilized, economic depression faded and economic development gained ground, the stress factors and forced migrations became a thing of the past. Migration processes again began to be shaped by economic factors, i.e. labor demand and differences in the standard of living and wages.

The actual impact of economic factors on migration became apparent in the first half of the 1990s, when the Russian Ruble played the role of the CIS’s universal currency, replacing the ersatz money of the newly formed states. In 1994, the influx of migrants in Russia reached 1.1 million and then was dramatically upset by the conflict in Chechnya. Be that as it may, the huge influx testified to the exceptional attractiveness of Russia for the population of the former partners in the Soviet Union and outlined the scope of their migration potential.

The increase in labor demand in Russia, resulting from its economic recovery against the background of its working population loss, on the one hand, and a large supply of labor in other CIS countries due to their economic backwardness and high unemployment rate on the other hand, were the basic factors shaping migration in the 2000s.

A transition to a natural decline in working age population occurred in Russia in 2007, and by the end of the decade, the loss had reached 1 million people a year.

However, labor shortages made themselves apparent in the very early 2000s, when labor resources still continued to grow (in 1995-2000, the working-age population increased by 1.2 million people), and the economic recovery was only emerging. Moreover, Russia experienced a large influx of population [3].

Unfavorable demographic conditions, coupled with an economic boom, created momentum for snow-balling expansion of foreign labor immigration, which quickly became the major migration flow and a sore spot for migration policy.

According to official data, the share of foreign workers in 2009 was 3.1% of the total labor force in Russia, while experts estimated the share of unregulated employment within the range of 8-10%. This is comparable to the share of migrant employment in Germany, Great Britain, and Italy.

During the 2000s, migration policy and measures for control were primarily aimed at finding legal instruments to regulate labor migration, which developed mainly informally.

During the 2000s, the government and the general public began to realize the depth of the demographic crisis and its implications for the country’s development, security and territorial integrity. As the economy required more and more foreign workers, migration problems became aggravated as well as an acid test for the state of society. Heated discussions on migration and its role in the life of the country, on whether or not the country needed migrants or could do without them, never stopped throughout the past decade and continue up to present day.

In every presidential address made before the Federal Assembly, both Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev have characterized demographic challenges and migration issues as vital problems for public administration. President-to-be Vladimir Putin in his pre-election manifesto article entitled “Russia: The National Question” covered the migration problem in a special section [4], thereby recognizing it as one of the issues of national priority.

From the viewpoint of migration policies, the Soviet period can be divided into two stages. The first one came to a close with the end of forced migration and the abolition in 2001 of the Federal Migration Service of Russia, which was created in the middle of 1992 as an independent state institution. Passed in 2002, the Federal Law On the Legal Status of Foreign Citizens in the Russian Federation and the new law on citizenship, as well as re-establishment of the Federal Migration Service as a part of the Ministry of the Interior marked the beginning of the second stage.

In addition to coping with internal problems, much attention in the decade under discussion was paid to promoting constructive cooperation with CIS countries.

Labor migration in Russia is a powerful and real actionable instrument with impressive potential for strengthening CIS integration trends. Migration here is a decisive factor, contributing to poverty reduction and a more equitable distribution of wealth among countries. Its role (not only in the CIS) in promoting international communication on a personal level is no less important. Thus, migration contributes to strengthening social stability and the development of integration processes in the Commonwealth of Independent States.

The 2000s were marked by increased attempts by CIS countries to manage migration processes with joint efforts. Russia, as the hosting country, is the main actor in this vein.

On October 5, 2007, the CIS Council of Migration Service Agency Heads was set up in Dushanbe. The CIS Heads of State also signed there the Declaration On Coordinated Migration Policy, the adoption of which at such a high level was additional evidence of the importance attached to migration problems by all the Commonwealth member-states. The Declaration confirmed their intentions of pursuing a coordinated immigration policy, promoting and protecting the rights of migrant workers, preventing discrimination, harmonizing migration legislation, as well as developing migration programs and carrying them out.

The Program of CIS cooperation in the field of combating illegal migration has been underway since 2006.

Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia are members of the Single Economic Space that has functioned since the beginning of 2012. The creation of the Eurasian Union is next in turn.

In 2011, all the parties to the Single Economic Space adopted and ratified the Agreement on the Legal Status of Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, which guarantees their citizens freedom of movement and employment in each participating country. The next step will be the harmonization of labor and immigration legislation, as well as visa policies in the long run. These goals were set by V. Putin in his address to the Board of the Federal Migration Service on January 26, 2011 [5].

At its meeting in Chisinau on November 14, 2008, the Council of CIS Heads of Government decided to start the creation of a CIS common labor market. The question of the single labor market was first put on the agenda of the CIS back in the 1990s. Because it proved unrealistic in those days, another attempt to make it a reality was made within the framework of the Eurasian Economic Community. However, this was not successful either. Nevertheless, the project of creating a single labor market in the CIS has never been removed from the agenda.

The history of the CIS Convention on the Legal Status of Migrant Workers and Members of their Families illustrates the difficulties in working out the agreed intergovernmental decisions in the sphere of labor. The Convention was signed at the abovementioned meeting in Chisinau, and it took 7 years to negotiate its provisions.

Now, since the Single Economic Space has become a reality, the effort to create a common labor market can finally bear fruit.

MIGRATION PROCESSES IN THE 2000S

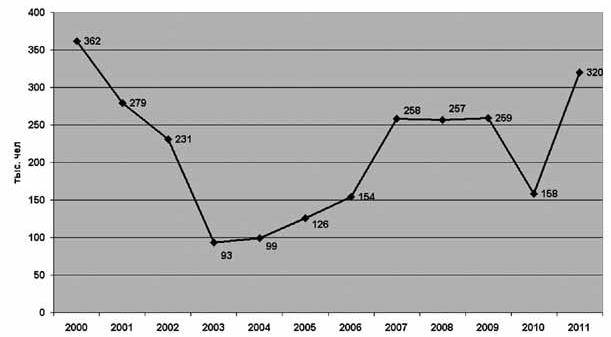

The role of migration in the population replenishment of Russia during the 2000s looks quite modest if measured against the previous decade. In the 1990s, migration increased the country’s population by an unprecedented 4.6 million people, which is 2.4 times more than in the 1980s. Fig. 1 shows the migration boom brought about by the collapse of the Soviet Union. However, it was not enough to make up for the population loss due to natural causes that coincided with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Migration in the 1990s compensated for only 70% of the natural loss.

Fig 1. Migration increase in Russia, thousands of people, 1981-2010

Source: Rosstat.

Data from 1981-2002 were recounted by Rosstat on the basis of 1989 and 2002 censuses, respectively; data from 2003-2010 conform to the current statistical account, modified by Rosstat.

In the 2000s, net migration fell to 1.9 million people, which looked like a return to the 1980s, i.e. to the normal position. But this similarity in figures is quite deceptive, since it conceals fundamental differences. A significant migration increase in the 1980s accounted for only 20% of total population growth, the main source of which at the time was due to a natural increase. In the 2000s, an almost similar in size migration made up for only 30% of population loss due to natural causes.

However, due to a significant number of unregistered migrants, the reality is very different from what the statistics indicate. It is not accidental that the two censuses conducted in the new Russia considerably increased the migration component of its population growth: by 1.7 million people in 2002 and by 1 million in 2010 [6]. Given the census correction data of one million, the replenishment rate of the population loss due to natural causes in the 2000s increased up to 45%, which is also much lower than in the 1990s.

Therefore, in the 2000s, the compensative effect of migration decreased, posing a serious challenge to the future development of Russia, as it is the only source of population growth against the background of population loss due to natural causes.

In the first decade of the 20th century, the population of Russia declined by 3.4 million people, dropping to 142.9 million at the beginning of 2011 against 146.3 million at the beginning of 2001 and 148.5 million in 1992.

In actuality, the 1990s marked the transition of the demographic situation in Russia to a critical phase, since maintaining the country’s population at a relatively stable level requires population inflows on a scale far surpassing previous ones. Thus, migration has acquired strategic value for the development of the country, which largely determines population density, security, economic development and the “appearance” of the people.

Demographers have warned about this for a long time, actively participating in TV debates and writing many articles for academic and mass media outlets, but in the turmoil of the 1990s, few cared about demographics. Society started to grasp the gravity of the situation only when the country came close to a collapse in the natural growth of the able-bodied population.

Recently, the information system of the Federal Migration Service has provided an opportunity to acquire data about the actual number of migrants. According to this system’s data, at the end of 2011 there were 9 million migrants in Russia. This figure leads us to believe that in the 2000s, Russia remained one of the major countries in the world in receiving migrants (after Germany and the U.S.), maintaining the position it occupied in the 1990s.

In fact, the number of migrants is even larger, since it does not allow for those who arrived in Russia before and have stayed in the country without registration.

Out of 9 million migrants, 3.3 million people came for personal reasons, to stay for a short time (to pay a visit, for medical treatment, tourism, etc.), or to study; 1.3 million officially worked. The remaining 4.3 million are mostly migrant workers, who are registered but work informally without permission [7]. Taking into account the 0.3 million who have come to Russia for permanent residence, the indefinite remainder is 4 million people.

The scope of illegal migration, made public by the FMS, almost coincides with expert estimates of 4-5 million obtained on the basis of earlier studies (see: J.A. Zaionchkovskaya and E.V. Tyuryukanova Migration and Demographic Crisis in Russia). There are estimates that this figure may even be twice as much, allegedly making it “about 10 million people” [8], but no substantiation has been provided.

According to selective opinion polls, from 16% [9] to 25% [10] of illegal migrants have almost permanently lived in Russia for several years. The average of these values leads to the conclusion that about 1 out of the 4 million illegal migrant workers are de facto permanent residents of Russia and, therefore, should have been added to net migration. The addition of this component, along with the census one, brings the net migration of the 2000s closer to the level of the previous decade. But even in this case, migration has performed its compensatory function by only 60%.

The influx of migrants has improved the structure of the Russian population, smoothed over sexual imbalances and partially compensated for labor supply deficiencies in the most sought-after age groups. The vast majority of migrants (75-80%) are of working age with more than half of them being 20-39 years old, while the share of migrants older than the working age is more than 2 times lower than in the population of Russia.

The migration trend of the 2000s is highly unstable (Fig. 2). However, it is caused by numerous changes in the rules of admission and registration of foreign citizens over the past 10 years rather than actual changes in the dynamics of migration flows. The underestimation of the importance of reliable statistical information has resulted in the non-comparability of the annual data, artificially created zigzag migration trends, and significantly hindered extrapolation forecasting.

Fig 2. The migration trend of the 2000s (net migration), thousands of people

Source: Rosstat data.

After the Law On the Legal Status of Foreign Citizens came into effect in 2002, the information database on initial registration of migrants, accumulated by statistical bodies, was dramatically reduced, since the latter no longer received information on migrants staying in Russia for 1 year or more, which had always been included in statistical data on migration [11]. In fact, the long-established system of migration controls was destroyed and had little to do with reality. As a result, net migration in 2003-2004 fell to insignificant values (Fig. 2). However, thanks to corrective efforts made by Rosstat, migration statistics gradually started to reflect reality beginning in 2004. Since 2007, migrants who were granted temporary residence permits for the period of one year or more for the first-time, started to be registered, and in 2011, the same applied to individuals receiving such permits for a period of nine months to one year and more [12]. Thus, a significant share of migrants was taken into account which immediately entailed a migration increase.

It should be noted that the significant migration decline of 40% in the post-crisis 2010 is comparable with a 50% reduction in net migration, caused by the crisis of 1998. The 1998 crisis has mad it possible to see the impact of the changing economic situation on migration flows. Then a reduction in net migration due to increased exit and decreased entry has lasted for almost a year, after which migratory trends began to return to pre-crisis levels [13]. As for the current crisis, its effect on migration became apparent after May 2008, then wasn’t felt much in 2009, but turned quite noticeable throughout 2010. Unfortunately, the incomparability of 2010 and 2011 statistical data does not allow for tracing whether the crisis trends continued in 2011 or started to fade.

External migration flows in the 2000s never reached the level of the 1990s in terms of both immigration and emigration. Immigration has decreased by half (3.5 million people [14] vs. 7.1 million people), but particularly striking is the decline in emigration figures: from 4.3 million to 716 thousand.

Inadequate monitoring characterizes both these flows, but the reasons concerning exchange with the countries of the CIS on the one hand and other countries on the other hand are different. In the CIS, imperfect monitoring is explained by disorganized systems for migrants’ registration and complicated procedures of registration until mid-2007, when they were considerably simplified. As for emigration, in the first years after the collapse of the USSR, the scale of departure from Russia was largely provoked by the division of the army, the return to the former republics from the northern regions and moving back to one’s native land in general.

After the completion of resettlement caused by the emergence of the new countries, Russia’s relations with CIS countries became almost entirely immigration-oriented, since the movement from Russia to former republics practically ceased. In 2011, 22.6 thousand people left Russia, which constitutes only 7.2% of the immigration flow [15]. All in all, over the period of 11 years only 384 thousand people emigrated from Russia to the former republics (Table 1). Of course, this figure is probably inaccurate, but it is doubtful that the underestimation is significant. Migrants who have managed to gain a foothold in Russia value their stay, while CIS countries seem unlikely to attract Russians.

Table 1. External migration of Russia, thousands of people, 2001–2011

| Immigration | Emigration | Migration increase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2414 | 716 | 1698 |

| Including | |||

| CIS countries* | 2258 | 384 | 1874 |

| Other countries | 156 | 332 | -176 |

* Including Georgia.

Source: Rosstat.

Immigration from the “other countries” is basically negligible, but this figure (as, incidentally, in the case of emigration) is additional evidence of imperfect statistics. In fact, both flows are considerably larger.

Russia has developed business relations with these countries, the balance of which is steadily developing in favor of Russia. For example, in 2011, 3753 thousand foreign citizens from countries other than CIS came to Russia on business trips (duty journey), while the corresponding number of Russians leaving on a business trip abroad was 85.5 thousand less. This imbalance in favor of Russia is typical for the entire post-Soviet period. Many people coming to Russia for business purposes stay for a year or more. According to the Ministry of the Interior data, in 1992-1997 their number exceeded one million (1,117 million) [16]. It’s reasonable to assume that among the visitors who have come for private purposes, the share of those who stay for a long time is rather significant too. By including in the data mainly citizens returning home after long stays abroad, statistics shape the image of Russia as a closed country, which is not true in reality. So, in 2010 out of 11.1 thousand registered immigrants not from the CIS countries, eight thousand were citizens of Russia. According to FMS, in 2011 in line with the program of attracting highly skilled professionals from visa-free countries, 16,540 people came to Russia mainly for a period from one to three years. The citizens of these countries received more than twenty thousand residence permits [17].

Emigration flows to CIS countries do not differ much between countries. This phenomenon appeared in the early 2000s and indicates an entirely new reality compared with the 1990s.

The conditions of leaving the country have changed, and Russia now has lifted many restrictions that used to be in force. Leaving Russia for another country of residence, one does not have to renounce their Russian citizenship, turn in real estate (residential, cottage, etc.), or get crossed off the register. Since immigrants often do not register their departure from the country, the statistics on emigration in the 2000s are not as representative as those from the 1990s, although the latter were incomplete too.

In the 1990s, about 1.5 million people emigrated from Russia to countries other than CIS member-states. Most of the emigrants were ethnic Jews, Germans, Greeks and people of other nationalities returning to their historical homelands, and emigration in this period peaked. In the next period, ethnic emigration declined rapidly because many of those willing to depart had already left, and conditions prompting departure changed too. It seems reasonable to assume, that the flow of emigration without prior arrangements was close in size to the registered one.

Statistics indicate that 332 thousand migrants left Russia for countries other than the CIS in 2001-2011. Clearly, this figure does not reflect actual emigration, since it does not include students, trainees, children studying abroad, and persons traveling to work abroad.

Each year foreigners adopt 4-6 thousand Russian children, while 10-15 thousand Russian women receive bride visas and go abroad. According to some estimates, 300-400 thousand work in Western Europe in the sex services and entertainment spheres [18].

In the current demographic situation, it would be important to know how large losses the Russian population has suffered in addition to those related to natural causes.

Emigration outside the CIS is a permanent channel for brain drain from Russia since its independence, and even before – for example, at the end of the 1980s, when emigration of Jews, Germans, and others was allowed.

According to estimates by Professor S. Egerev, the total number of Russian scientists working abroad at the end of 1998 was about 30 thousand. 14-18 thousand out of them pursued basic sciences [19].

According to more recent data, the number of Russian scientists working abroad is estimated at between 50 and 200 thousand people [20]. Physicists, biologists, and mathematicians appear to be in exceptionally high demand. Usually scientists receive an invitation to come on a business trip and stay abroad for a long period of time or even permanently. Thus, 20 per cent of them stay abroad for 3 years or more. The United States and Germany are at the top of the list of the countries, hosting Russian scientists (30 and 20 per cent, respectively), followed by France, Great Britain, Japan, the Scandinavian countries, and others [21].

The number of Russian students studying in OECD countries in 2008 was estimated between 35 and 50 thousand, up against 3 million students who study abroad. Thus, one cannot say that higher education abroad appears quite attractive for Russians. What is worse is that about half the students and interns do not intend to return home.

The increase in Russian migration is entirely due to its CIS partners. In addition to 1.8 million people registered in net migration figures (Table 2), all the unregistered increases of about 2 million people mentioned in the comments to Fig. 1, should also be attributed to CIS countries. In the aggregate, we see about 4 million entrants over the past decade.

Table 2. Migration increase of the Russian Federation in relations with the CIS countries and Georgia, thousands of people

| 2001–2005 | 2006–2010 | |

|---|---|---|

| Western countries | 114,0 | 251,1 |

| Byelorussia | -1,3 | 8,5 |

| Moldavia | 33,3 | 67,1 |

| Ukraine | 82,0 | 175,5 |

| Transcaucasia | 80,7 | 265,5 |

| Azerbaijan | 18,3 | 89,3 |

| Armenia | 28,5 | 137,7 |

| Georgia | 33,9 | 38,5 |

| Central Asia | 248,4 | 430,5 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 61,5 | 111,2 |

| Tajikistan | 27,2 | 91,3 |

| Turkmenistan | 27,3 | 19,3 |

| Uzbekistan | 132,4 | 208,7 |

| Kazakhstan | 215,5 | 152,5 |

| Total | 658,6 | 1099,6 |

Source: Current statistics.

Central Asia appears to be the main donor for Russia, providing nearly 40% of migration inflow (Fig. 3). Its role has remained invariably high during the entire post-Soviet period, and continues to rise (38.6% in the 2000s compared to 32.3% in the 1990s.). But migration from Kazakhstan, which used to occupy the leading positions in migration inflow to Russia, has dramatically decreased. Migration from Transcaucasia increased in the second half of the 2000s, remaining as a whole during the decade at the level of the 1990s. The same is true for Ukraine.

Has Russia missed its chance to attract skilled workforces? Although many believe that this is the case, we have every reason to assert that Russia has not missed its chance to replenish its population with highly skilled and culturally similar migrants. Russia has left the door open to immigrants, even if it does not receive them with open arms.

Fig 3. The Structure of Russian Migration Increases by CIS countries, %

| Kazakhstan | Central Asia |

| Western countries | Kazakhstan |

| Transcaucasia | Western countries |

| Central Asia | Transcaucasia |

From 1992 to 2007, after which monitoring of migrants on a national basis was canceled, Russia received an influx of population very close to its own according to ethnic structure. Russians comprised 2/3 of the inflows and 80% together with Ukrainians, Belarusians and others nationalities, living in the country.

By the 2000s the inflow of Russians decreased. The share of Russians together with other nationalities living in Russia, having reached three quarters in the period of the highest migration wave (1993-1997), dropped to a half in 2003-2007, whereas the share of the Central Asian peoples rose from 1.3% to 6.8%. The inflow of Russians decreased faster than other nationalities and faster than their shrinking potential in the post-Soviet space. It indicated a slackening of nationalism and the gradual adaptation of Russians to new social conditions, on the one hand, and the difficulties they faced when returning Russia, on the other hand. Moreover, in many CIS countries a growing demand has emerged for the professional skills possessed by Russians living there.

Given this trend, the adoption in 2006 of the Federal program of resettlement of compatriots was truly late. Its effect so far has been insignificant, and there seems to be no reason to expect a substantial increase in the inflow of nationals in the future [22]. The above program fell into the same trap as the previously adopted one on receiving displaced people, i.e. countless legal and administrative barriers on the way to resettlement. The new program offers migrants more freedom in decision-making, introduces new preferences, but is still burdened with limitations [23].

Table 3 shows that the chance to attract educated migrants was not missed either.

Table 3.Level of education of international migrants (2004)* and Russian population (2002),** %

| Higher education | Incomplete higher education | Specialized secondary education | Secondary education and incomplete secondary education | Primary education | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population of Russia | 16,2 | 3,1 | 27,5 | 44,4 | 8,8 | 100 |

| Immigrants | 19,7 | 3,1 | 30,4 | 43,1 | 3,7 | 100 |

| Emigrants | 19,0 | 3,3 | 27,9 | 45,6 | 4,2 | 100 |

| Migration increase | 20,9 | 2,7 | 34,9 | 38,6 | 2,9 | 100 |

*Current statistics, 14 years old and older.

**2002 census, 15 years old and older.

As we see, migrants’ level of education was higher than that of the country’s population. However, against the background of economic collapse and the suspension of production activities, there were few possibilities for using their professional skills. Similar to the native population, who had no work, migrants were forced to make a living by doing odd jobs and, as a result, lost their skills. At the same time, former specialists, including migrants, finding no use for their education, became the driving force behind market development. They actively set up small businesses, established wholesale and retail trade with complex infrastructure, creating jobs not only for themselves but for the local population too. In other words, the potential of vocational training has been successfully applied in these new fields of activity.

The increased share of migrants from Central Asia has considerably lowered the average level of education of newcomers. Thus, in 2010 only 14.3% of them had higher education and 23.1% – secondary vocational education. These indicators are the lowest for migrants from Azerbaijan and Tajikistan, many of whom are from rural areas: 9-10% and 16%, respectively. Presumably, the level of education of temporary labor migrants is even lower.

The trend in Russia was quite the opposite. According to the 2010 census, the percentage of people with higher education rose to 23% (almost 1.5 times compared to 2002), and with a vocational one – up to 31%.

Thus, by the end of the 2000s there appeared a significant gap in the level of professional education between migrants on the one hand and the Russians on the other which, coupled with cultural differences, objectively gave an impetus to development of xenophobia.

Such a sharp decline in the educational level of migrants within a relatively short period of time suggests that the professional migration potential of CIS countries has been largely exhausted.

This means that Russia’s hopes of solving the problem of providing its economy with skilled workers by recruiting them from CIS countries are unfounded. The hopes that they could obtain the required vocational training in their home countries are just as vain, since professional standards in Russia have left the ones of the major donor countries far behind. Russia will have to train workers on-site, particularly in blue-collar jobs.

To promote development of high-tech modern manufacturing in Russia and restore its prestige in global science, new measures were adopted in 2010 that encouraged highly skilled professionals from abroad to come in Russia for work. These professionals are offered a number of benefits, such as legal preferences and decent remuneration by international standards. Work quotas do not apply to this group of migrants, work permits can be issued for up to 3 years and repeatedly extended, specialists and members of their families are offered residence permits, etc. Since May 2010, when the corresponding Federal Law 86 was adopted, 47.1 thousand foreign specialists have come to Russia for work, including 27.4 thousand in 2011. 16.5 thousand out of them were from the countries with a visa system. 10% of experts are from Germany; 7.9% – from the UK; 7.4% – from the U.S.; 4-5% – from France, Turkey or China. Two thirds of the specialists work in management.

The practice of inviting highly qualified professionals has not become widespread in the Russian regions. Mostly Moscow and Moscow region take advantage of this new opportunity and account for 86% of work permits granted to professionals from abroad [24].

ILLEGAL MIGRATION

FMS data, along with assessing the total number of migrants, has confirmed the prevalence of uncontrolled migration in Russia, almost all of which is concentrated in the employment sector. If the overall number of legitimate migrants roughly equals the number of illegal migrants, in the employment sector the legitimate migrants make less than a quarter, while three-quarters of migrants work illegally.

The nature of illegal migration in the post-Soviet period has undergone a number of significant changes. In the 1990s, especially after the law on freedom of entry and exit came into force at the beginning of 1993 and Russia opened its doors, illegal migration was associated primarily with uncontrolled border crossings, drug trafficking and smuggling. This explains why the first efforts in the fight against illegal migration were concentrated on migration control and restricting migration by enforcing severe legal requirements. Laws On the Procedure for Exit from the Russian Federation and Entry into the Russian Federation (1996) and On the Legal Status of Foreign Citizens (2002) were passed. The latter imposed strict legal provisions, leaving little room for legal workers. The excessive strictness produced the opposite effect and provoked an increase of unregulated migration. For example, in the mid-2000s no more than 15% of migrant workers worked legally. The main barriers to formal employment were registration (residence permit) and the complex procedure of job placement.

It was at this time that criminal systems for shadow recruitment and human trafficking were set up and strengthened, the slave exploitation of migrant labor gained ground, and the migration basis for widespread corrupt practices formed.

Gradually it became clear that the best way to curb illegal immigration came down to simplifying legal procedures. As FMS Director K. Romodanovsky put it – “Wherever there are restrictions, there is always corruption and cheating people.” [25] This statement is a vivid example of a new approach to the management of migration.

In mid-2007, the state decided to introduce fundamental changes in law enforcement. The Federal law On Migration Registration of Foreign Citizens and Stateless Persons in the Russian Federation replaced authorization-based registration (residence permit) by simple notification that made the registration process accessible and decisively simplified, although did not remove all the problems associated with it. After the introduction of simplified rules the vast majority of migrants got registered, whereas before only half of them could do it, mostly in exchange for bribes. Simple registration procedure also made it possible to assess the number of migrants in the country.

At the same time procedures for obtaining work permits for migrants coming from non-visa countries were simplified in the same decisive way. Permits in the form of labor cards were delivered to migrants themselves instead of their employers, as the old regulations stipulated. In addition, migrants received the right of a free job search and the right to change their employer. The results, as in the case of registration, were quite impressive. According to surveys, most migrant workers (75%) obtained labor cards, but not all employers were willing to hire workers officially. Although only one out of three migrants with labor cards could officially get a job on legal grounds, this was 2 times higher than the pre-reform level of legitimate migration. Accordingly, tax allocations increased too. About 40% of migrants and 60% of employers welcomed the reform.

According to the FMS, liberalization of legislation has at least halved illegal immigration [26]. Expert estimates are less optimistic – 1.5 times [27].

The impact of the economic crisis. The crisis of 2009 prevented the legal reforms from coming to a close and made it impossible to fully assess their efficiency. To bring down the xenophobic wave provoked by rising unemployment, the rules of employment of migrant workers have been again toughened and have become even more severe than before the reforms.

In addition, the government announced anti-crisis measures that gave preference to the local labor force, reduced quotas for hiring foreigners by half, introduced a list of occupations for which migrants could be hired, and obliged employers to declare vacancies. The unemployed were encouraged to move to other parts of the country with targeted support. 5.3 thousand people seized this opportunity.

Despite these austerities and numerous radical appeals to urgently withdraw migrants from Russia, the economic crisis has not affected labor migration as much as was expected. According to the Ministry of Health and Social Development of Russia, the demand by Russian constituent territories for foreign workers in 2011 compared to 2010 decreased by only 10.2%, and those from countries with a visa regime – by 18.2%. According to various estimates (such as from the FMS and experts), the number of migrant workers has decreased by 15-20%. The level of 20% is confirmed by research on Tajikistan [28]. Migrants are choosing to wait for better times, surviving on odd jobs.

As before the crisis, the vast majority of migrants did work. Unemployment among them markedly rose, but still remained low (3% and 7% before and after the crisis, respectively) [29]. Shadow employment increased, since even law-abiding employers were forced to hire workers against the rules due to dramatically reduced quotas.

Despite lower formal employment, remittances during 2009 continued to grow, testifying to the escalation of migrants’ illegal employment [30].

However, this trend was not true for all countries. In 2009 compared to 2008, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan faced a very noticeable drop in remittances by 31% and 20% respectively, but they did remain above the level of 2007 [31]. Due to transfers, both countries managed to achieve economic growth and escaped depression.

Political scientists find it inappropriate to use the term post-Soviet space in respect to contemporary realities, since the countries that emerged from the ruins of the Soviet Union are displaying a growing divergence of political orientation and other interests [32]. Without casting further doubt on this subject, we note that in terms of migration and labor markets, this space (except Baltic states) still remains common, and actively functioning migration networks strengthen CIS countries’ interdependence.

In general, the crisis affected permanent migration more than labor migration.

The introduction of patents in mid-2010 for migrant workers, which delivered household services for individuals, was a palliative measure. Due to the simple procedure of their offering, by the end of 2011 more than 1 million migrants obtained them [33], including those employed by legal entities in circumvention of the law. Be that as it may, patents helped one million migrant workers come out of the shadows. As a result, the size of illegal employment apparently remained at the pre-crisis level.

Perhaps, it would be worthwhile to legally extend the patent system to at least unskilled labor employed by entities. This would generate extra income for the state budget and significantly reduce the problem of segmentation in labor migration.

In general, the protective orientation of anti-crisis efforts (in general against migrants), however did not lead to mass deportations or administrative expulsion of migrant workers. Therefore, the government has recognized by default (as well as by introducing patent system) the appropriateness of their presence in the country.

The tolerant attitude towards migrants has helped to maintain stability in the CIS countries even during the crisis. The mass exodus of migrants from Russia and the discontinuance of migrant remittances would have meant for some countries (e.g. Tajikistan) a real threat of economic collapse and would call into question the continuation of the Eurasian integration process.

According to surveys, during the crisis the earnings of migrant workers fell more that those of the Russians, and the gap between them increased to 20% compared to 10-15% before the crisis.

Interestingly, earnings and housing conditions of legitimate migrant workers and those who work without a permit hardly differ. In other words, legal migrant workers possess no tangible advantages over illegal ones, which if they existed, might encourage the latter to legalize [34]. As long as this situation persists, it is difficult to expect a reduction of illegal migration.

It is hardly reasonable to hope that the scope of shadow employment of migrants would be smaller than that of the native population. According to various estimates, 20-25% of the Russian labor market is in the shadow. Since informal employment of labor migrants must be larger by definition, it comes down to 2/3 with only one in three workers receiving earnings in the official economy.

MIGRATION CHALLENGES

Migration is a complex social process, which is essential for development but at the same time is fraught with risks of social destabilization.

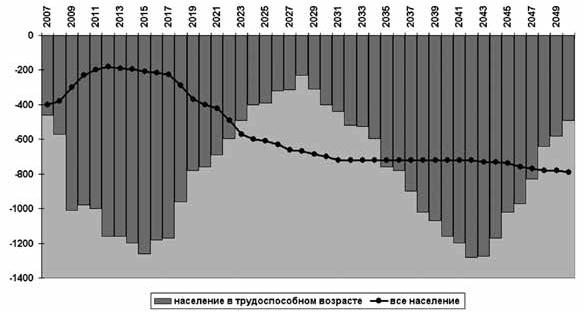

One way or another, migration challenges for Russia are connected with the current and anticipated demographic situation. The most serious demographic challenge to the economy is due to the reduction of working age population, which began in 2007 and is rapidly gaining momentum.

Fig 4. Expected working age population loss due to natural causes in Russia until 2050, thousands of people per year

Working age population Total population

Source: Forecast of the HSE Institute of Demography, medium variant .

According to the medium variant of the Federal State Statistics Service's latest forecast, during the period of 2011-2030, the decline in the working age population (if the working age remains the same) will reach 11 million people (Table 4), provided that the loss of another 4 million is expected to be compensated for by migration. The loss of the country’s labor potential due to natural causes is expected to last until at least the middle of the century (Fig. 4). Consequently, labor will be one of the scarcest resources in Russia for a long time.

It should be noted that the reduction of labor potential in the first two decades does not depend on the birth rate, as almost all the young people to enter the labor market at this time have already been born.

Can an economy with a shrinking labor supply grow successfully by increasing the latter’s efficiency only?

The experience of countries that are far ahead of Russia in terms of economic development shows that it is very difficult. At least no developed country has ever set an example of economic growth, accompanied by systematically declining employment, despite much higher labor productivity compared to that observed in Russia.

Under these circumstances it seems quite natural to consider making the most of internal labor resources and, above all, the possibility of increasing the retirement age, which in Russia is lower than in most developed countries. Table 4 clearly shows that raising the retirement age does little in terms of meeting labor market demands and may be motivated by deficits in the pension fund.

Table 4Able-bodied population loss due to natural causes under different working ages, millions of people

| Working age, years | 2009–2025 | 2026–2050 |

|---|---|---|

| 16–59 (54) | 13 | 18,8 |

| 16–64 (for men and women) | 12,2 | 18,5 |

Source: Forecast of the HSE Institute of Demography, medium variant .

According to estimates, mobilizing internal resources can make up for about half the labor resource deficiency.

How many immigrants are required under this scenario?

With a 70% share of able-bodied population among migrants, which reflects Russian specifics over recent years, but is higher than the forecast of Rosstat, the required immigration for the period up to 2030 amounts to approximately 12 million people.

Measured against the current presence of migrants, this figure does not look frightening. The existing number of migrants confirms the high absorption capacity of the country. The unsettled legal status of many migrants affects the quality of flows and the latter’s degree of legitimacy rather than its size.

Fig. 4 suggests another important conclusion. In the upcoming period, Russia's economy will have to function against the background of dramatic and brisk fluctuations in the labor force supply. This necessitates creating instruments and a flexible system of migration management that could be quickly modified.

In fact, the quota approach could probably produce the desired result, provided there is a reliable technique of assessing the objective demand for migrants. The second important condition is that the quota (or some other) approach will not be used for timeserving political purposes, as it what has happened during the current crisis.

A no less serious challenge to Russia is caused by the dynamics of total population growth.

Even an influx of 12 million migrants cannot meet the demand in labor force for all Russian regions. Only those with the greatest potential for growth may count on relatively favorable scenarios. Consequently, the demographic crisis, and migration conditions in particular, will contribute to a polarization of different Russian regions in terms of economic development.

Siberia and the Far East in the next decade will at best see a slowdown in migration outflows. The situation may improve in the mid 2020s - early 2030s, when the working-age population loss will reduce sharply. In the long term, as Fig. 4 shows, the situation will worsen again dramatically.

Another serious challenge is due to the fact that migration is becoming more culturally distinct. The rapid increase of those from Central Asia has already provoked an increase in xenophobic attitudes among Russians, although these migrants are socially still quite close to the native population. But CIS migration resources are insufficient to meet the needs of Russia in the future. The Russian potential by many estimates does not exceed 3-4 million, and the establishment of the Common Economic Space makes it even less. The potential of the titular ethnic groups of the CIS countries does not exceed 6-7 million people.

In any case, to make up for the arising demographic deficit, Russia will inevitably have to resort to large-scale immigration from other countries. Countries of Eastern Europe, close to us culturally, would certainly be the best donors, but to lay hopes on this would be irrational. The global market for immigrant labor is very competitive, and competition will only grow until the middle of the century. Since Russia cannot compete with the U.S. and the European Union as an equal, its choices are limited and come down mainly to the countries of Southeast and South Asia and, perhaps, the Middle East.

The looming influx of immigrants, differing greatly from the population of Russia in ethno-cultural respects, threatens to split society and destabilize it. Immigration has become a real bone of contention, an election campaign issue, a dividing line of ideological movements, and a cornerstone for nationalists.

Russia has inherited the traditions of a closed country, and its experience in managing ethnically heterogeneous immigration is limited.

However, considering these pros and the cons, one should keep in mind what the alternative might be – an economic downturn with a subsequent decline in living standards, stagnation, lower wages, incomes and pensions, and an escalation in poverty. Unfortunately these obvious and extremely painful consequences of rapid working-age population loss are never discussed during debates on migration, while they are the real “horror stories”, not to mention the possible disintegration of the country.

In June 2012, the Concept of the State Migration Policy of the Russian Federation up to 2025 was adopted. The official document makes it clear that the immigration of foreign workers is a positive development, which is necessary for Russia’s further economic development. This puts an end to debates on whether we need migrants or not.

The new concept is aimed at actively attracting migrants into the country to compensate for the population loss due to natural causes, labor deficiencies and to develop innovative potential.

The guidelines are defined as follows: an emphasis on permanent migration as the most effective way to attract specialists, educational migration, opening new channels of mobility, including vacation student migration, and a differentiated approach to different flows of migrants. For the first time a concept paper carries a provision concerning the personal interests of citizens: hiring workers for household tasks. This is a symptomatic sign.

Great importance is attached to promoting the adaptation and integration of migrants, establishing constructive interaction between migrants on the one hand and the host community on the other. A system of measures is designed to facilitate the achievement of this task. Their expediency is not questioned.

However, it is difficult to expect the successful implementation of integration programs if the share of illegal migrants continues to stay at the present intolerably high level. Legalizing them is a must on the way towards their integration, reducing migration risks and fighting corruption in the sphere of migration.

Migration has already become a defining factor of Russia’s development in terms of economic growth and social stability. Migration policy should keep pace with developments in this sphere and sometimes even anticipate them. So far, unfortunately, this is not yet a reality.

The papers in this section offer a more detailed analysis of migration situation. They cover the pressing problems of migration policy (interviews of Director of the Federal Migration Service of the Russian Federation K.O. Romodanovsky and Rector of the National Research University “Higher School of Economics” Ya. Kuz’minov, who headed the Strategy 2020 expert group on migration and labor market), reveal the impact of migration on demographic factors (article by A.G. Vishnevsky), and analyze in detail external (publication of J.A. Zaionchkovskaya, E.V. Tyuryukanova) and internal migrations (publication of N .V. Mkrtchyan).

NOTES

1. Zaionchkovskaya J. Migration Trends in the CIS: Results of a Decade / / Migration in the CIS and the Baltic States: from Diversity of Problems to Common Information Space / Ed. G. Vitkovskaya, J. Zaionchkovskaya. Moscow, 2001, p.182

2. Ibid. p. 184

3. Here is what economic magazines wrote, assessing the labor force situation in 2000: on the situation in Yekaterinburg – “Skilled machine operators and turners meet with a ready market... Russian migrants from neighboring Kazakhstan hold out a helping hand” (see: Chelovek I trud, # 10, 2000, p. 56); on the situation in Perm: “Industrial giants, returning to life after the crisis, face increasingly an acute shortage of workers..." (see: Expert. 2000. № 30. p. 23.); on the situation in St. Petersburg: “On average, there are three job opportunities for every unemployed” (ibid. p. 22.).

4. Vladimir Putin Russia: The National Question / / Nezavisimaya Gazeta. , January 23, 2012. URL: http://www. ng.ru/politics/2012-01-23/1_national.html

5. Activities of the FMS of Russia in 2011 / / Proceedings of the enlarged session of the Federal Migration Service Board, FMS, Moscow, 2012. p. 8.

6. I believe that although the censuses left much to be desired, the net migration calculated on their basis is certainly not exaggerated, but rather, as in statistics, underestimated.

7. Speech by K.O. Romodanovsky, Director of Federal Migration Service of Russia / / Activities of the FMS of Russia in 2011 / / Proceedings of the enlarged session of the Federal Migration Service Board, FMS, Moscow, 2012. p. 18.

8. N. Vlasova: Legalization of Illegal Immigrants: the Relevance and the Risks / / Migratsia XXI Vek, 2012. # 2 (11). March-April. p. 32.

9. The population of Russia in 2008. The Sixteenth Annual Demographic Report / / Ed. A.G. Vishnevsky, Moscow. HSE Publishers, 2010. p. 267.

10. J.A. Zaionchkovskaya, E.V. Tyuryukanova,Yu.F. Florinskaya Labor Migration in Russia: How to Move On. New Eurasia Foundation. Moscow, 2011, p. 25.

11. For details see: The Population of Russia in 2005: The Thirteenth Annual Demographic Report / Ed. A.G. Vishnevsky, Moscow. HSE Publishers, 2007. p. 186-189; O.S. Chudinovsky Legal Basis of Statistical Observation of Migration Flows in Russia / / Voprosy Statistiki, 2006, # 8.

12. The Law On Legal Status of Foreign Citizens defines two types of temporary registration in Russia: the place of residence for up to three months and the place of temporary residence for a period of 1 year or more. Migrants, who register at the place of temporary residence for 9 months, practically spend in Russia one year, as the first 3 months they were registered at this place of residence. This was the reason for their inclusion in the statistics. In 2011 this category of migrants (internal and external combined) made 1.2 million people or 35.3% of the total number of arrivals, including 216 thousand people staying for 9 months to a year.

13. The population of Russia in 2000. The Eighth Annual Demographic Report / / Ed. A.G. Vishnevsky, Institute of Economic Forecasting, Russian Academy of Sciences, Center for Demography and Human Ecology, Moscow, 2001. p. 102-203.

14. Including 1 million people, added in line with the 2010 census. Statistically immigration numbered 2.4 million people.

15. Please note that we are talking about migrants who move permanently or for a period of 1 year or more.

16. The population of Russia in 1999. The Seventh Annual Demographic Report / / Ed. A.G. Vishnevsky, Institute of Economic Forecasting, Russian Academy of Sciences, Center for Demography and Human Ecology, Moscow, 2000, p. 141.

17. Activities of the FMS of Russia in 2011 / / Proceedings of the enlarged session of the Federal Migration Service Board, FMS, Moscow, 2012. pp. 116, 125.

18. V.N. Archangelsky, A.E. Ivanov, V. Kuznetsov, L. Rybakovsky, SV Ryazancev Strategy for Demographic Development of Russia. Moscow, 2005. pp. 44-45.

19. S. Egerev C. Draining Brains / / Moskovskiye Novosti. 1998. # 46.

20. G.A. Vlaskin, E.V. Lenchuk Industrial Policy in Transition to an Innovative Economy: Experience of the Countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the CIS. Moscow, 2006, p. 203.

21. For details see J.A. Zaionchkovskaya Labor Emigration of Russian scientists / / Problems of Forecasting, Moscow, International Academic Publishing Company “Nauka/Interperiodica” , 2004, # 4. pp. 98-108.

22. Over the course of the state program, 62.5 thousand people settled in Russia, including 31.4 thousand in 2011, when new benefits were introduces. (Activities of the FMS of Russia in 2011 / / Proceedings of the enlarged session of the Federal Migration Service Board, FMS, Moscow, 2012, p. 64)

23. Interview Looking for Work Themselves by A. Zhuravsky, Department Director of the Ministry of Regional Development of Russia to Migratsia XXI Vek magazine, 2012. # 4 (13), July-August. pp. 24-27.

24. Activities of the FMS of Russia in 2011 / / Proceedings of the enlarged session of the Federal Migration Service Board, FMS, Moscow, 2012, pp. 116-117.

25. Interview to Rossiyskaya Migratsia magazine, 2009, # 5-6 (36-37), August-September, p. 2.

26. Speech by K.O. Romodanovsky at the enlarged session of the Federal Migration Service Board on January 31, 2008.

27. For details on the results of the reform, see: New Legislation of the Russian Federation: Law Enforcement Practice / / Ed. G. Vitkovskaya, A. Platonova, V. Shkolnikova, IOM, the FMS and the OSCE. Moscow, 2009.

28. Saodat Olimova Work Loses Sense / / Rossiyskaya migratsia, 2009, # 5-6 (36-37). August-September, p. 36.

29. Migration and Demographic Crisis in Russia / Ed. J.A. Zaionchkovskaya, E.V. Tyuryukanova; “New Eurasia” Foundation, Center for Migration Studies, Institute of Economic Forecasting. Moscow, 2010. p. 39.

30. N. Vlasov Legalization of illegal immigrants: the Relevance and the Risks / / Migratsia XXI Vek magazine, 2012. # 2 (11). March-April, p. 33.

31. Martin Brownbridge, Canagarajah Sudarshan What Is the Impact of Remittances on Economic Growth in the CIS Countries? / / Migratsia XXI Vek magazine, 2011, # 1 (4), January-February, p. 29.

32. Dmitry Trenin. Post-Imperium / / Carnegie Moscow Center, Moscow, 2012, p. 65.

33. Activities of the FMS of Russia in 2011 / / Proceedings of the enlarged session of the Federal Migration Service Board, FMS, Moscow, 2012, p.19

34. E.V. Tyuryukanova Cheap Workers Are Expensive / / Migratsia XXI Vek magazine, 2010 # 1 p. 43.

(votes: 2, rating: 3) |

(2 votes) |