In the early 2000s, the international community has time and again used humanitarian pretexts to intervene in interethnic, inter-faith and other kinds of conflict in which civilans’ rights are threatened. What results has humanitarian intervention yielded? Does it have a future? Will it continue to serve as a geopolitical tool to reshape conflict regions to the West’s best advantage? And what region could become the next testing ground for this humanitarian intervention with geopolitical overtones?

Background

The idea of humanitarian intervention was first formulated by Bernard Kouchner, founder of NGO Medecins Sans Frontieres and future French Foreign Minister, in his book Le Devoir d'Ingérence (The Duty to Intervene) published in 1987. Kouchner insisted that to protect human rights, democratic states are entitled and even obliged to interfere in the affairs of other states, irrespective of their sovereignty.

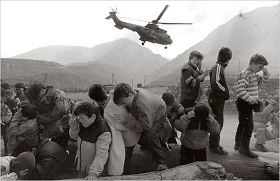

The first consciously humanitarian intervention of modern times was the NATO operation against Yugoslavia in 1999. Earlier the world community had responded to reports of humanitarian disasters either on a limited scale (as in the 1994-1995 NATO bombing of Bosnian Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina), or refrained from intervening altogether (as in the ethnic conflict in Rwanda in 1994, which saw up to one million lives lost.

Yugoslavia as a Proving Ground

The ideology for intervention in Yugoslavia was provided by the then Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who urged that the protection of human rights be considered a kind of missionary work. However, even then, many experts argued that by carrying out this humanitarian intervention in Kosovo the U.S.-led West was adopting a new format of the armed intervention: the Kosovo crisis showed America's new willingness to act as it feels right, regardless of international law [1]. As British military expert John Keegan correctly observed, the victory won in the Balkans by the Air Force was not just a victory for NATO or a victory for the moral reasons for fighting the war. “This is a victory for the New World Order that President Bush declared after the Gulf War”[2].

It is no surprise then, that the idea of humanitarian intervention went on to become a key trigger for disputes and controversy in international relations [3]. As a concept, it is in direct conflict with the principles of sovereignty, territorial integrity, and the United Nation’s authority, as set out in the UN Charter. In addition, NATO's humanitarian intervention in Yugoslavia gave rise to a catastrophic humanitarian crisis, with a million refugees fleeing Kosovo.

In Search of a Niche for Foreign Law

In 2000, the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty was established in order to create a legal framework for humanitarian intervention under the auspices of the UN. In 2001, the Commission published the report The Responsibility to Protect, stating the need for the concept of the right to intervene used in Yugoslavia to be replaced by the concept “responsibility to protect.” This new approach emphasizes nonmilitary methods, and interprets foreign intervention as states’ responsibility to protect the civilian population in another state, when said state is unable to meet its obligation to protect its own citizens. The international community’s responsibility with regard to violations of humanitarian law was formulated in three specific objectives, i.e. to prevent, to react, and to rebuild.

Although supported by leading Western states, the report has failed to deliver either an international convention or an amendment to the UN Charter. As a result, sanctioning a humanitarian intervention is still the prerogative of the UN Security Council. Furthermore, the International Court of Justice, looking at U.S. support for the armed anti-government forces in Nicaragua in the 1980s, noted that international law does not authorize the use of armed force by any state to remedy the serious violations of human rights in another country without the approval of UN Security Council. The relevant provision was confirmed by the General Assembly resolution of November 3, 1986. Therefore, in terms of international law, the concept of responsibility to protect has no more legitimate grounds today than it did at the time of NATO’s bombing of Yugoslavia.

Humanitarian Interventions in the 2000s: Ersatz Notion and Dubious Gains

In the 2000s, Western powers undertook humanitarian interventions in three countries – Afghanistan in 2001, Iraq in 2003 and Libya in 2011. In all three cases, military interference was executed in a form not authorized by the UN Security Council. In Afghanistan, U.S. and NATO operations took the shape of self-defense, albeit under the guise of protecting Afghan civilians from the Taliban. The Iraqi mission was carried out in the name of the search for weapons of mass destruction. Allegedly, Saddam Hussein had gone “to elaborate lengths… to build and keep weapons of mass destruction. His goal is to dominate, intimidate and attack” [4]. It was only later that President George W. Bush augmented the anti-Saddam campaign with a humanitarian component.

As for Libya, by adopting Resolution 1973 of March 17, 2011, the UN Security Council mandated only a no-fly zone to help protect civilians. From the very beginning, in all these cases, NATO forces were aiming at regime change, which was achieved. However, the humanitarian situation in Libya, Iraq, or Afghanistan became no better.

Thus, these three large-scale international military operations failed to implement a single guideline set out in the report Responsibility to Protect. The international community neither prevented the massive violations of humanitarian law that have taken place since the 1990s in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya nor responded to genuine signals nor rebuilt safety for the civilian population. And all of this is due to their ersatz notion. Instead of intervening to responsibly protect civilians, while maintaining a distance from the parties involved, external forces from the very start concentrated on providing military and political support to anti-government forces. In fact, this was direct participation in combat to reach their own geopolitical goals and refine the scenarios for future interventions in other strategic areas. Iraq and other theaters of conflict have become a testing ground for new principles of American foreign policy [5].

The settlement of the Darfur conflict appears to be the only successful example of international intervention under humanitarian rhetoric to take place in the 2000s. Under pressure from the international community, in 2006 in Abuja, the Sudanese government and the Sudan Liberation Movement signed the Darfur Peace Agreement. This international intervention was a success due to its purely humanitarian purposes and the absence of any external desire to see regime change.

Responsibility in Protection: Signboard Change or Impasse Exit Strategy?

World leaders offer their own ways to overcome this international legal deadlock over humanitarian intervention. At the March 2012 BRICS summit, President of Brazil Dilma Rousseff proposed replacing the concept of responsibility to protect with responsibility while protecting based on the recognized need to shield civilians not only from their own dictators but from intervening forces as well. At the 66th session of the UN General Assembly in September 2012, representatives of Brazil and other countries stated that the use of force carried the risk of causing unintended casualties, and at times made a political solution more difficult to achieve.

However, the relevant UN bodies seem reluctant to support this approach due to the geopolitically motivated need for uncertainty in the interpretation of humanitarian intervention. Washington has already advised Brasilia to refrain from amending the current practice of interference under humanitarian pretexts and recommended that it stick to the U.S. version.

Humanitarian Intervention as a Geopolitical Tool

As a result, today the terms humanitarian intervention and humanitarian catastrophe “do not carry any significant legal weight from the standpoint of international law” and are farmed out to politicians and the military. International legal instruments in general, and the sources of the law for armed conflicts in particular, “do not contain any definition of such concepts”. Therefore, humanitarian intervention, regardless of the actual situation in the conflict zone, has become a convenient propaganda screen, disguising the West’s geopolitical agenda. This agenda is built on scenarios involving either the forced change of regimes deemed “undesirable” or the establishment of direct military and political control over regions rich in natural resources or that are attractive in some other way. At the same time, the genuinely tragic situation on the ground in many hotspots offers international players unique foreign-policy opportunities such as trading their support for intervention in one area for the opportunity to pursue a more independent policy in another. Former German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, who supported the NATO operation against Yugoslavia in 1999, reveals in his book that “after participation in the Kosovo operation, and agreeing to the operation in Afghanistan in November 2001 we felt free to say “no” to the war in Iraq” [6].

Looking to the Future

We have every reason to believe that the concept of responsibility to protect lacks any clear foreign definition in law and offers scope for a very broad range of interpretations, but that at the same time remains the foundation for Western intervention motivated by the intervening parties’ geopolitical interests. The balance of forces in conflict regions portends further Eastward advances – from Syria through Iran towards Pakistan, and further to the Korean Peninsula and the broader Far East. The United States, NATO and the League of Arab States are known to have been ready for a humanitarian intervention in Syria in June-July 2012, when about 100 bodies were found in the Syrian town of Al-Houla. However, international observers in the country refused to clearly lay the responsibility with government forces. This, coupled with the continuing divisions within the anti-Assad coalition, ruined the Western humanitarian intervention scenario. The report by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry into the Syrian Arab Republic only stated that the collected evidence does not rule out any of the options under consideration, including that it was the responsibility of anti-Government forces. Nevertheless, Syria remains the prime candidate for becoming the next case of humanitarian intervention with geopolitical overtones.

1. Glennon M. The New Interventionism / / Foreign Affairs. 1999. May-June.

2. The Daily Telegraph, June 04, 1999.

3. Hehir A. Humanitarian Intervention after Kosovo: Iraq, Darfur and the Record of Global Civil Society. Basingstoke, 2008. P. 1.

4. The New York Times, January 29, 2003.

5. The New York Times, April 10, 2003.

6. Gerhardt Schroeder, Decisions: My Life in Politics.