Food Security in Central Asia

Farmers, Rankul, Tajikistan

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

Director of Rural Infrastructure and Agro-Industry Division at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, Professor

Central Asia today incorporates five countries: Kazakhstan and former Soviet Central Asian republics. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, these countries went through their own individual transformations, leading to a highly diversified socio-economic picture today. One of the most acute issues countries in the modern world face today is food security.

Central Asia today incorporates five countries: Kazakhstan and former Soviet Central Asian republics. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, these countries went through their own individual transformations, leading to a highly diversified socio-economic picture today. One of the most acute issues countries in the modern world face today is food security.

What is Food Security?

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines food security as physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet the dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life for all people [1].

Physical access (to food) depends on domestic production and import capability. Domestic production is determined by a country’s comparative advantages in producing basic foodstuffs, i.e. by the effectiveness of food production. We often lose sight of the fact that food is no longer simply produced at the farm or in the fields. That’s just the basic produce. The share of agriculture proper in the final food cost is falling all the time. The larger share of these costs comes from processing, packaging, storage, transportation, and trade. Hence, even if a country is able to turn out major volumes of produce on its own, if it lacks a sufficiently advanced market infrastructure physical access to food will remain low.

Physical access (to food) depends on domestic production and import capability.

Stable food imports largely rely on a country's positive balance of payments, since the cash is needed to bring in foods from the global market. However, recent volatility in global food processes has skyrocketed, causing uncertainty over imports. Hence, well-off countries with limited natural resources rush to acquire as much food as possible. Interestingly, domestic production is by no means a fireproof way of ensuring a guaranteed supply. Against this backdrop we have seen a particular kind of food import scenario develop. China is establishing production in numerous countries in Africa and in Tajikistan [2], and the Persian Gulf states are following suit by leasing land broad, for example in Ukraine, thus delivering greater stability in external supply. Poorer countries and those countries whose massive purchases have a direct impact on world prices need to have buffer production capacity and reserves to ensure physical access to food.

Economic access to food depends on people's incomes and evenness of their distribution. The greater the poverty – the larger the groups of people who are starving or malnourished. Since rural areas are usually harder hit by poverty than urban areas, and quite a lot of rural residents are net buyers of food, it is wrong to think that economic accessibility of food increases with rising rural incomes resulting from higher food prices. That would only see more malnutrition in urban areas. The rural population could also become richer through boosting production efficiency. However, that would inevitably cause a reduction in the number of farmers operating in any one area. There is potential for a rise in non-farming jobs in the countryside, but most redundant workers usually head to the cities. With no income source easily on offer there, the problem of famine simply shifts from rural to urban areas. Therefore, the key solution to the problem of economic access to food seems to lie in economic growth and fair distribution of the resultant revenues.

Economic access to food depends on people's incomes and evenness of their distribution.

Finally, better physical or economic access to food will hardly help if food quality is poor. Raising food quality and safety is another critical component in improving a nation’s food security.

Uneven Food Supplies in Central Asia

Since domestic production of basic foods fails to meet demand, these countries have to rely on agricultural imports, leaving them vulnerable to global price fluctuations and impacting their export revenues. At the same time, it is important to note the situation in each country is different.

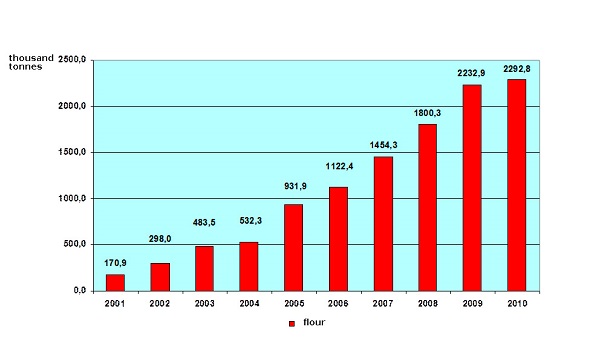

Kazakhstan has become the region’s main supplier of flour. The world’s largest grain exporter, Kazakhstan faces problems accessing the external grain markets, primarily in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, because Ukraine and Russia enjoy much lower transportation costs. As a result, Kazakhstan has become the global leader in flour supply that to Central Asia. Although practically all countries in the region are working to develop their own grain programs, these efforts have not resulted in significant success. For example, Turkmenistan has to apply administrative levers to force domestic food processors and cattle breeders to buy locally produced flour and grain, which is more expensive and of inferior quality to Kazakh imports. All countries in the region, except Kazakhstan, lack natural and climatic advantages for grain production, and have no real experience in its production. Their grain is not competitive, as it is invariably more expensive and of poorer quality.

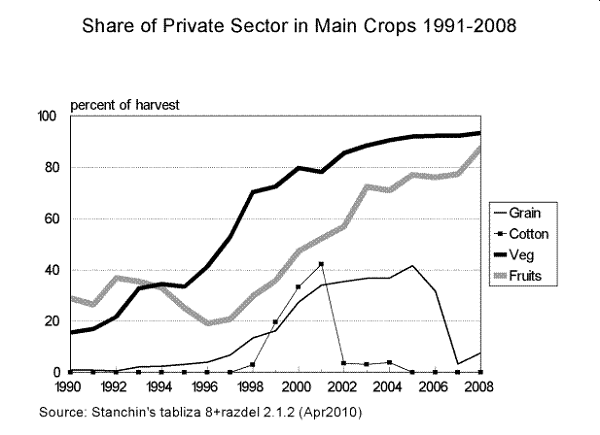

In Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, food crops face traditional competition with from cotton that offers much higher revenues than grain on the global market (for example South Georgia, In Central Asia (Table 17.1). This is particularly true for Turkmenistan, which produces fine-fleeced quality cotton, with market conditions ruling out grain production in volumes meeting domestic needs.

In the Soviet period, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, despite their size, were the region's largest meat producers and exporters, but farming reforms have practically wiped out large-scale meat production [3]. All governments in the region are working to develop the sector, but so far to no avail.

Dairy production is even more concentrated in households, a major problem from a food quality/safety perspective.

Fruits and vegetables are also grown at household level, with imports only existing in large cities.

Figure 6. Private sector in main crop production 1991-2008

Source: Stanchin’s table 8 and section 2.1.2 (April 2010)

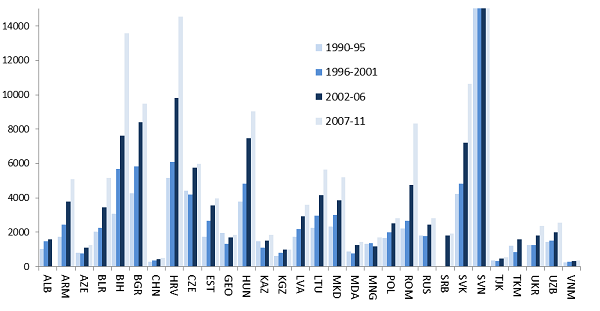

The region's main problem is in low farming efficiency, which is the lowest and slowest among all post-communist countries (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.Farming productivity in Central Asia, one of the lowest and slowest in growth among post-socialist countries

Source: World Development Indicators

This suggests that regional supplies will not increase in absence of major sectoral reforms. In most cases, governments are trying to boost productivity at large enterprises set up through budgetary allocations or with heavy state subsidies. Frequently, the effect is quite convincing, although no country in the region possesses the economic potential to speedily create a critical mass of such firms for domestic needs or exports. Consequently, the emphasis should be on raising the effectiveness of small producers through developing special institutions, such as rural education, and establishing a targeted marketing infrastructure for small farms, wholesale markets, cooperatives, milk collectors, small slaughterhouses, etc., as well establishing as a strict quality control system for feedstock. Small-scale production also needs its own credit system. All this should be provided with proper regulatory support and legislation. It is high time for the states to drop the ever-popular romanticized idea of self-sufficiency.

In other words, widespread access to food is not yet something Central Asia can boast.

Economic Access to Food in Central Asia

Horizons of Russian Engagement.

Working paper X / 2013

In fact, economic access to food seems to be even worse, with Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan among the countries with the world’s lowest food security level [4]. The poverty line in other countries in the region is slightly lower, but still high. While per capita GDP is growing, this growth is quite unstable.

The fragmentation of agricultural production and the food industry generates an extra challenge for building a modern food security system, since setting up a system to exert quality and safety controls over produce supplied by small farms is a relatively complex technical, economic and social endeavor. Compared to an agro-industrial firm, a small farm finds it much more difficult to meet the latest quality requirements, a situation that is only aggravated by the absence of any traditions of this kind of quality control.

Using FAO data, the Economist Intelligence Unit has developed the Global Food Security Index covering 106 countries [5], including Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. The Index reflects three food security components, each used to calculate a separate index as a composite of several parameters.

Food availability is assessed by parameters such as sufficiency of supply, public expenditure on agricultural R&D, agricultural infrastructure, political instability, etc. Affordability is understood through looking at food consumption as a share of household expenditure, the poverty line, the presence of food safety net programs, etc. Food quality and safety refers to the level of proteins and microelements in a portion, the presence of a food quality control system, etc. Table1 shows that the gravest food situation is in Tajikistan, which comes 86th of the 106 countries assessed (by comparison, Russia is ranked 39th). And the Table clearly shows that the key reasons for low food security are poverty and poor welfare systems (for example in Tajikistan, only 23 percent of allowances reach the 20 percent of the poorest population group [6]) as well as other factors such as food affordability, rather than low production levels.

Table 1.Food Security Index for Countries in Central Asia, 2013*

| Kazakhstan | ||||

| Tajikistan | ||||

| Uzbekistan | ||||

| Russia | ||||

| Hungary | ||||

| Germany | ||||

| United States | ||||

* The higher the rank, the better the situation in the country

Source: calculated by data at: http://foodsecurityindex.eiu.com/

However, a low food security ranking does not mean starvation or malnourishment. According to FAO and the World Bank, the malnourishment level in Central Asia stands at 5-6 percent, except for Tajikistan where this figure exceeds 30 percent. At the same time, malnutrition among mothers and children remains a critical problem. According to UNICEF, in Central Asia (not including Kazakhstan) in 2008-2012, 20-26 percent of children suffered from limited growth, while 12 percent were underweight (compares with five percent in Russia during the same period) [7]. When children suffer stunted physical growth at an early age there are significant hurdles for society’s long-term development as human potential deteriorates.

Factors in Future Development

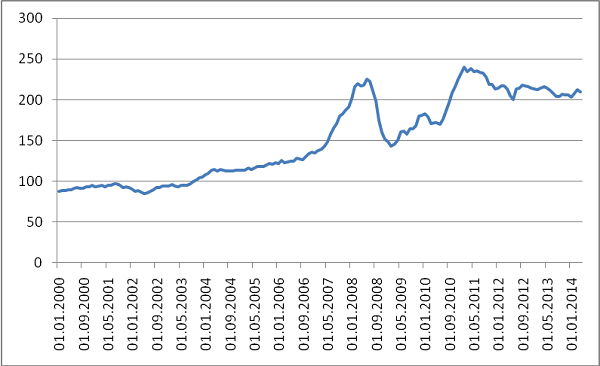

The key factor in regional food supply instability seems to lie in economic access to food, while the short-term improvement of the situation could be achieved by raising incomes. The per capita GDP growth definitely provides only a partial picture of the poverty level in a country, but it remains the most reliable indicator out of all the data covering the region. And Figure 2 clearly shows that per capita GDP is growing, albeit in an unstable way.

Remittances from labor migrants in neighboring countries, mostly Russia (Table 1) are of greater significance for the region. In the mid-2000s, the revenues of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan were one-third based on these transfers, and today Tajikistan is the world leader with 50 percent of its GDP formed from remittances in 2011 [8].

| Kazakhstan | |||

| Kyrgyzstan | |||

| Tajikistan | |||

| Turkmenistan | |||

| Uzbekistan | |||

Source: www.ifad.org; econ.worldbank.org

At the same time, international humanitarian assistance to the region is the lowest among all the post-socialist countries (Figure 3), suggesting its fairly insignificant role in supporting food security. On the other hand, after the 2007-2008 crisis, the World Bank and the EBRD have been generously investing in regional agriculture and the food sector.

In future, progress made on food security should visibly differ country to country, Tajikistan certainly posing the greatest challenge. It is one of the 32 poorest countries in the FAO rating. But even there, since 2000, we have seen stable economic growth, with a five-fold increase of per capita GDP delivering an almost 50 percent drop in poverty since 1999, to 6.5 percent in 2009. These figures are country-average, while some Tajik areas, such as the Pamir Mountains, remain very poor. Households’ dependence on remittances makes revenues rather uncertain. For example, the 2007-2008 crisis saw the money wired back home fall by one-third [9].

The key reasons for low food security are poverty and poor welfare systems as well as other factors such as food affordability, rather than low production levels.

Nevertheless, the rapid improvement of the situation in the country that is, economically, the weakest, could open up opportunities for greater food security across the entire region.

Russia's Role

If it is to have a positive impact, helping the region raise food security, Russia should focus on eradicating poverty.

To this end, Moscow could help Central Asia establish a social insurance system, something Russia may ostensibly boast. Economic development assistance, greater caution in trade (for example, imposing restrictions on imports from these countries) and in migration policies (for example, restrictions on labor migration from the region) might make a visible contribution to improving food security in Central Asia.

Another problem related to food quality and safety could become a mutually beneficial project through the building of a common Russia-Central Asia food security environment, such as a system for transboundary animal disease control.

1. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2001 (Rome: FAO, 2002).

2. http://www.ucentralasia.org/downloads/UCA-IPPA-WP16-FoodSecurity-Rus.pdf

3. Even in Kazakhstan, which is known for its large-scale meat cattle breeding, in 2013 large enterprises sold only 13 percent of the total meats (calculated using data of Kazakh Agriculture Ministry, http://mgov.kz/napravleniya-razvitiya/zhivotnovodstvo/). In Tajikistan, large enterprises account for only three percent of total meat output (http://www.ucentralasia.org/downloads/UCA-IPPA-WP16-FoodSecurity-Rus.pdf).

4. https://www.gafspfund.org/sites/gafspfund.org/files/Documents/Country_Guidelines.pdf

5. http://foodsecurityindex.eiu.com/

6. http://www.mehnat.tj/index.php/ru/sotsialnoe-obsluzhivanie/227-pilotnaya-programma-sotsialnoj-pomoshchi-v-tadzhikistane

7. http://www.unicef.org/statistics/

8. FAO. The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2013 http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3434e/i3434e.pdf

9. ibid

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |