Financial Markets in Central Asia: the Light in the Middle of the Tunnel

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

PhD in Economics, MBA, Lead Research Fellow (Center for International Economic Relations Studies), Institute for Finance and Economic Research, Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia

A relatively mature banking sector in Kazakhstan, attempts to overcome uncertainty in Kyrgyzstan and isolationism in Turkmenistan, the obvious dependence of credit institutions in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan on administrative interference – these are part of the diverse set of characteristics that inevitably undermine the strategic initiatives of Russian banks, driving them to clusterization in capital and caution. Are there any opportunities being overlooked and are the market risks really that high?

The widely discussed post-crisis settlement in the financial sector, the European sovereign debt situation and the Cypriot banking crisis have experts of all kinds riveted to financial issues, while the new Grand Game in Asia is attracting attention from all over. A relatively mature banking sector in Kazakhstan, attempts to overcome uncertainty in Kyrgyzstan and isolationism in Turkmenistan, the obvious dependence of credit institutions in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan on administrative interference – these are part of the diverse set of characteristics that inevitably undermine the strategic initiatives of Russian banks, driving them to clusterization in capital and caution. Are there any opportunities being overlooked and are the market risks really that high?

Banking Risks in Central Asia

Central Asia is an emerging market, with micro-level certainty reduced by volatile market economies and national currencies, as well as the divergent development of financial sectors and their priorities. The situation is aggravated by imperfect banking regulations and prudential supervision, the non-transparent operations of some actors, as well as by the specifics of the business climate and interactions between regulators and government bodies.

Although the political and economic ties between Russia and countries in the region underwent large changes in the 1990s, the local economies became entangled in controversial policies. As a result, the principles behind multilateral relations were intertwined with unyielding regionalism characterized, among other things, by the unilateral and biased interpretations of some basic cooperation criteria. Hence, interbank links remain weak.

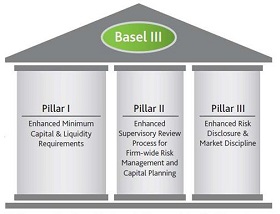

Basel III was supposed to strengthen bank

capital requirements by increasing bank

liquidity and bank leverage

Empirical research of Central Asian countries shows that foreign-capital banks are considerably helping to alleviate post-crisis scenarios.

However, local markets do need stable credit institutions with broad capabilities, including access to global markets, efficient operational models and corporate management, as well as the ability to resist crises. Empirical research of Central Asian countries shows that foreign-capital banks are considerably helping to alleviate post-crisis scenarios [1]. In other words, their mature risk management practices are improving the macro-prudential balance. Economic positivism is also seen at the micro-level: an analysis of 368 bank subsidiaries belonging to 68 international credit institutions in 47 developing countries from 1994 to 2008 shows that foreign actors considerably raise the competiveness of local banks, improve the business environment and ensure stable growth in the banking sector [2].

But incursion also has a reverse side, as foreign-capital banks may carry with them outside shocks emanating from countries where they are headquartered, with the dimensions of distress hinging on macroeconomic dynamics for markets risks and other specifics of corporate strategies. Frequently, strategic myopia toward sensitive economic segments takes place, such as reluctant credit practices with regards to medium and small businesses with preferences geared at making less arduous operations with large-scale clients to minimize the period prior to profiting. On the other hand, the causes of this credit one-sidedness may be lie in the difficult of determining and confirming the reliability of smaller firms. Informational asymmetries build up if a local market has been penetrated through the acquisition of an existing local bank, which usually involves lower crediting for small companies and consequently slower development of small businesses (causing the dissatisfaction of local authorities), higher bankruptcy risks and increased social tensions. At the same time, the establishment of an institution from scratch normally stimulates the real economy due to operational agility required for new businesses.

National Bank of the Republic of Kazakhstan

Analysis of 368 bank subsidiaries belonging to 68 international credit institutions in 47 developing countries from 1994 to 2008 shows that foreign actors considerably raise the competiveness of local banks, improve the business environment and ensure stable growth in the banking sector

Risks for Russian banks may also arise from an excessive concentration of capital within singular financial clusters, exemplified by the Kazakh city of Almaty. As of March 1, 2013, the share of credit investments of Almaty banks made up 53.0 percent of total credits issued by Kazakh banks, whereas the specific overall debt on the same date was 62.8 percent [3]. The high concentration of assets gives rise to rat-race competition. Combined with the particularities of the business environment, this may cause significant fading in strategic landmarks and operational flexibility, hampering the attainment of key efficiency parameters and regulation requirements.

Despite their lead among some parameters and the legal entity status enjoyed according to Kazakh law, Russian banks are alienated from major national and regional projects where local institutions dominate. This means that they are not seen as systemically important and in case of a disturbance, would not receive financial support. As a result of administrative and regulatory restrictions, Russian banks may suffer considerable operation cuts or bans, especially if their revenues turn out to be critical for overall profits. In addition, major companies may be forcibly switched over to local banks for servicing (1). Regulatory protectionism is also likely to limit foreign capital’s share in the local banking sector and cripple future growth of these bands. If Russian-Kazakh trade and economic cooperation diminish, Russian banks may altogether stagnate, if their operational model becomes too integrated in bilateral activities.

Without a doubt, existing, expected and supposed risks make local banking less attractive, especially due to the set of volatile elements specific to immature economies. At the same time, targeted and consistent government steps to make financial markets more transparent obviously signify a shift toward the development of predictability that might become permanent. In this context, the point lies is reforming banking regulation and oversight, as well as achieving convergence with global standards (2) to ensure stability in the banking sector. In terms of efficiency, Kazakhstan offers the most vivid example of banking reforms. Since Russian banks are adequately represented only there (three banks in total) (3) , it appears reasonable to compare parameters of their activities with other foreign banks (see Table).

Basel III is a document produced by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision providing advice on banking regulation. The paper aims to overcome deficiencies in financial regulation uncovered by the 2008 global financial crisis, and contains new requirements for the structure of internal funds, the sufficiency of share capital and tier-one capital, as well as the sufficiency of share capital and aggregate capital taking into account a safety cushion.

Table Comparative Parameters for Foreign Banks Operating in Kazakhstan

(as of March 1, 2013)

| Bank | Current ratio (4) | Repayment capacity factor (5) | Capital multiplier (6) | Non-performing credits (percent), as of January 1, 2013 | Interest margin (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russian-capital banks | |||||

| Alpha-Bank | 0,578 | 0,667 | 6,254 | 2,36 | 5,27 |

| VTB bank | 0,781 | 0,826 | 5,853 | 2,81 | 7,03 |

| Sberbank | 0,710 | 0,727 | 8,345 | 5,48 | 5,49 |

| Foreign-capital banks | |||||

| HSBC | 0,964 | 0,370 | 7,766 | 7,41 | 3,53 |

| RBS | 1,075 | 0,361 | 5,520 | 3,59 | 1,04 |

| Citibank | 1,069 | 0,314 | 10,882 | 16,89 | 1,77 |

Source: National Bank of Republic of Kazakhstan

Existing, expected and supposed risks make local banking less attractive. At the same time, targeted and consistent government steps to make financial markets more transparent obviously signify a shift toward the development of predictability that might become permanent.

Comparative analysis convincingly proves that Russian banks take more risks in their credit policies. Although the minimum liquidity rate established by the Kazakh regulator is 0.3, their liquidity is under the banking sector average (0.803 as of January 1, 2013) and considerably lower than that of the foreign banks in question (by 0.346 basis points on the average). Low liquidity seems to arise from dynamic credit activity, which points to the prioritization of short-term profits and runs against Basel III and the new regulatory paradigm; this leads to a risk of exposing operational shortsightedness displayed by a preference for limited traditional and high-margin banking products and services. The latter seems to emerge from high interest margins or cheap funding from their headquarters in Moscow, instead of getting funds on local financial markets. This resource infantilism may become costly, since poor market integration could become a time bomb if regulation and supervision become tighter.

An assessment of risks should not neglect certain disquieting trends on the macro-prudential level. Economic overheating and lower banking efficiency are indicated by hiking bad loans – by 39.2 percent in 2012 to make 22.1 percent of the total principle debt as of January 1, 2013, i.e. a rise of 4.8 percentage points in 12 months. At the same time, the loan portfolio during the same period reached only 11.3 percent, while the share of banking assets in Kazakhstan’s GDP has tended to consistently decline – from 46.5 percent on January 1, 2012 to 44.1 percent 12 months later (8).

Parameters of Key Regional Banking Risks

Economic overheating and lower banking efficiency are indicated by hiking bad loans.

In Central Asia, exogenous and endogenous risks differ due to the asynchronous dynamics in banking development, the key ones being as follows.

Republic of Kazakhstan

Despite certain negative trends at the macro-level, Kazakhstan’s banking system is best prepared for hypothetical crises. Stability comes from adoption of Basel III standards in 2013-2018 (9), something other countries of the region have still failed to adopt. Due to enhanced regulatory requirements for capital adequacy, Russian banks may expect higher expenses in adopting the prescribed regulations, which may be followed by a reorientation of operational models toward more caution in crediting and better risk management.

Kyrgyz Republic

The country was quite adept in surviving the 2008-2009 crisis, but political volatility in 2010 brought about a 30-percent drop in the banks’ deposit base, primarily due to an outflow of non-residents’ assets. In comparison with Kazakhstan with its prevailing territorial concentration of assets, the local banking sector features institutional concentration, as 42 percent of all banking assets are held by three banks. Weak financial infrastructure and hard-to-get credits for the private sector constitute the second biggest factors retarding economic growth. There is no early warning mechanism against financial breakdown or an insolvency of credit institutions. Russian banks may face radical regulatory measures aimed at ensuring conformity with reforms and the growth of national banking. At that, political risks are likely to continue to trigger economic instability, entailing business closures and flights from the market.

Republic of Tajikistan

The general forecast for the local banking sector is beset by uncertainty. Steps taken to improve regulation and oversight appear to be insufficient for improving the effectiveness of the sectoral infrastructure and stimulating the growth of private sector. Risks to Russian banks emanate from macro-environment misbalances, i.e. poor governance, a fragile investment climate, direct government interference in the crediting process, as well as from on the immature micro-level, including non-transparency of state companies, popular mistrust of banks which breeds a poor deposit base and costly credits, inadequate control of contract execution causing many irretrievable loans, poor risk management in banks, and a lack of reliable funding sources.

Turkmenistan

The financial sector has just begun a move to match basic open-market requirements. Banking is under government control, which hampers its integration in regional financing, let alone on the global scale. The government sector accounts for 85 percent of total credits. The absence of adequate banking practices and restricted crediting of individuals and private businesses (10) make the key hurdles for foreign banks and export of their capital into the country.

Republic of Uzbekistan

Banking is dominated by government institutions, with 30 percent of the market monopolized by the National Bank for Foreign Economic Activity. Despite its independent status, the Central Bank is de facto a government instrument. The macro-level risks include an extraordinary integration of the state, economy and banking, as well as tough government controls over currency and cash operations. At the same time, economic risks hinge on political uncertainties, the greatest being the unsettled territorial disputes with neighbor states and volatility in Afghanistan. Macro-prudential risks boil down to the low quality and irregularity in the information made public by the banks.

Conclusions

The operations of a foreign bank in Central Asia depends not only on the degree of its integration in the local market, the satisfaction of clients and trust of its partners, but also on the status and the specifics of the macro environment. Otherwise, a bank could become stuck in the narrow niche of the sector’s lower echelon, with its strategic objectives threatened.

National Bank of Uzbekistan

The possible growth of government influence on financial markets, and the introduction of currency and other restrictions for foreign banks followed by lower competitiveness, constitute the key factors aggravating long-term risks for Russian banks in Central Asia.

To become a quality institution and reliability model, a Russian bank may find it insufficient to boast high capitalization and the stylish brand of the head office. Every effort should be directed towards meeting the needs of the economy and the population through high-level diversification of assets (including unique items adjusted to local markets for products and services), as well as reliable funding sources. A bank should require an immaculate operational model free from mechanistic mimicry, skilled personnel able to function in a hazy environment, a first-rate corporate culture and reputable business ethics. Prospects for organic and non-organic growth in a country (11) and in the region are vital for protecting a bank from market volatility and operational vulnerability. The prioritization of high-margin operations should be avoided, especially in fields dependent on non-market decisions and shifts. At the same time, in view of specific banking concentration and competition, as well as macro-level trends, and in order to maximize profits from external expansion, Russian banks should target markets featuring deficient banking infrastructure and an existing poor supply of banking products and services. Motivational signals are also welcome from local regulators that could treat such banks using differentiated norms of prudential oversight.

The possible growth of government influence on financial markets, and the introduction of currency and other restrictions for foreign banks followed by lower competitiveness, constitute the key factors aggravating long-term risks for Russian banks in Central Asia. Similar examples may be found in the complete or partial departure of some international banks (Svenska Handelsbanken, Santander, HSBC, Barclays, etc.) from Russia under pressure from major Russian actors. Although no Russian banks are known to have left Central Asia, strong risks to their potential do exist, at least before introduction of Basel III, the synchronization of the principles behind and environment for banking regulation and supervision, and the internationalization of the banking sector.

Literature

1. Clarke, G.R.G., Cull R., & Kisunko, G. External finance and firm survival in the aftermath of the crisis: Evidence from Eastern Europe and Central Asia // Journal of Comparative Economics. 2012. № 40 (3). P. 372-392.

2. Jeon, B.N., Olivero, M.P. & Ji, W. Multinational banking and the international transmission of financial shocks: Evidence from foreign bank subsidiaries // Journal of Banking & Finance. 2013. № 37 (3). P. 952-972.

3. National Bank of Kazakhstan. Statistical Bulletin. http://www.nationalbank.kz/cont/publish645703_10204.pdf (Accessed 04/19/2013).

4. European Investment Bank. Banking in the Eastern Neighbours and Central Asia: Challenges and Opportunities. 2012.

Notes

1. The author suggested the idea in September 2012 at a RIAC workshop. The appropriate risk scenario is given January 28, 2013 article “German Gref Accuses Kazakhstan Of Breaking Competition Rules” (http://bankir.ru/bank/news/93284/10035559).

2. Recommendations of Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (Basel III).

3. Less Promsvyazbank and Rosselkhozbank operating in Kazakhstan through a representative office, as well as Eurasian Development Bank with the IFO status.

4. Assets-to commitments ratio.

5. Loan portfolio-to-assets ratio.

6. Assets-to-internal capital ratio.

7. Net interest-to-earning assets.

8. http://www.afn.kz/attachments/105/271/publish271-1060237.pdf

9. http://finance.headline.kz/novosti/v_kazahstane_budut_vvedenyi_novyie_standartyi_basel_iii_.html

10. Only one percent of the population has bank accounts, one percent takes short-term loans, and one percent have mortgages (as of 2011) [4].

11. In Kazakhstan, Sberbank has 13, VTB – 17, and Alpha-Bank – 5 branches (as of 04/01/2013), http://www.afn.kz/index.cfm?docid=476

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |