The latest G7 summit was held at the picturesque Schloss Elmau in Bavaria on June 8, 2015. Russia, which is no longer a club member, this time cemented the G7 countries as a common enemy, and even brought back the importance of the Group, which five years ago (with Russia in it) was fading away and losing its ground. The huge impact of the G20 Summit in Toronto, coupled with almost complete silence (even among anti-globalists) with regard to the G8 Summit that preceded it, proves this.

The latest G7 summit was held at the picturesque Schloss Elmau in Bavaria on June 8, 2015. Russia, which is no longer a club member, this time cemented the G7 countries as a common enemy, and even brought back the importance of the Group, which five years ago (with Russia in it) was fading away and losing its ground. The huge impact of the G20 Summit in Toronto, coupled with almost complete silence (even among anti-globalists) with regard to the G8 Summit that preceded it, proves this.

To Be or Not to Be

Having tried and failed in 2014 to block the Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, the remaining G8 members came up with a less dramatic, but equally effective way of “punishing” Russia by stripping it of its presidency. But it may just have been that, having passed up on the opportunity to attend the spectacular opening ceremony of the Games in person, the leaders of the G8 countries did not want to be reminded of their huge mistake by going ahead with the planned summit in Sochi.

The main winner in this mess was the European Union. After all, the EU, which became a member of the Group in 1977, has ever since proved (mostly in the form of participation in G7/8 donor projects) that it belongs in this privileged “club”. It is thanks to Russia that this dream became a reality and European taxpayers’ money was recouped, with a G8 Summit finally being held under the formal presidency of the European Union in Brussels.

Russia’s response to the collective demarche of its former partners could be seen as being somewhat similar to the fox’s reaction in Aesop’s Fables. And there may be some truth in this from a psychological perspective. Nevertheless, permanent observers would surely have noticed the structural problems that had already became visible when Russia was still a member of the G8. The crisis in Ukraine, clearly provoked by the West, was a wonderful opportunity to cut the Gordian Knot. And it has little to do with the fact that, as Chancellor Angela Merkel has claimed, Russia is not a democratic country and does not share the club’s values.

The key issue here is that in strengthening its positions, Russia failed to accept the role of a junior partner, even in this exclusive group. The method of compensating the country’s ambitions to being a great power by gradually increasing its involvement in the G8 and slowly giving it more powers within the group may have worked in the 1990s. But, the granting of full rights in Kananaskis in 2002 (Russia received written recognition of its equal rights in the G8 and was included in the rotation order for presidency at the expense of Gerhard Schroeder, who stepped down a year earlier) should have led either to an overhaul of the hierarchy of interaction within the “club”, or to the gradual exclusion of Russia from the select group. Russia’s claims to equal leadership rights, coupled with the start of a general campaign on the part of major developing countries, inevitably led to the development of a second scenario. An attempt was made in 2008 to squeeze Russia out of the group by holding a separate meeting of the G7 ministers of foreign affairs. In 2012, Vladimir Putin failed to attend the G8 Summit in the US, citing the need to stay at home to form his government following the general elections (the sides were still treading carefully – Dmitry Medvedev was sent in Putin’s stead, and the NATO Summit was geographically removed from the G8). A year earlier, when Medvedev was still in power, the French contingent showed little consideration for the Russian President by holding its summit on a national holiday. Medvedev was forced to leave the summit a day early, before the signing of the final declaration.

A way out?

In 2015, the confrontation between Russia and the West, above all the G7 countries, has only intensified. And the Normandy and G20 formats have only showed that Russia is not prepared to simply give up and, if put under pressure, can fire back. Given Russia’s uncompromising attitude, the lack of a significant breakthrough in Ukraine, as well as serious failures of the U.S. policy on the Asian front (some of its key allies joined the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, or AIIB, for example), Washington could not under any circumstances afford to lose face by conceding to Putin.

This is why a comparison between the following events is intriguing. On the one hand, Frank-Walter Steinmeier and a host of public officials and business representatives in Germany have spoken about the need to bring Russia back to the G8. There is an empty “presidential suite” waiting for Putin. On the other hand, we have the latest spy scandal involving German intelligence service working with the United States National Security Agency (NSA). The country’s opposition is questioning country’s leader and there is speculation in the media about Barack Obama threatening to stay away from Garmisch-Partenkirchen if Merkel bows to the pressure of her fellow countrymen and discloses the information they are asking for. Or perhaps there is another explanation –Obama’s potential no-show could be motivated by the possible easing of relations between Germany and the Russians: “It’s me or Putin!”

Only Russia?

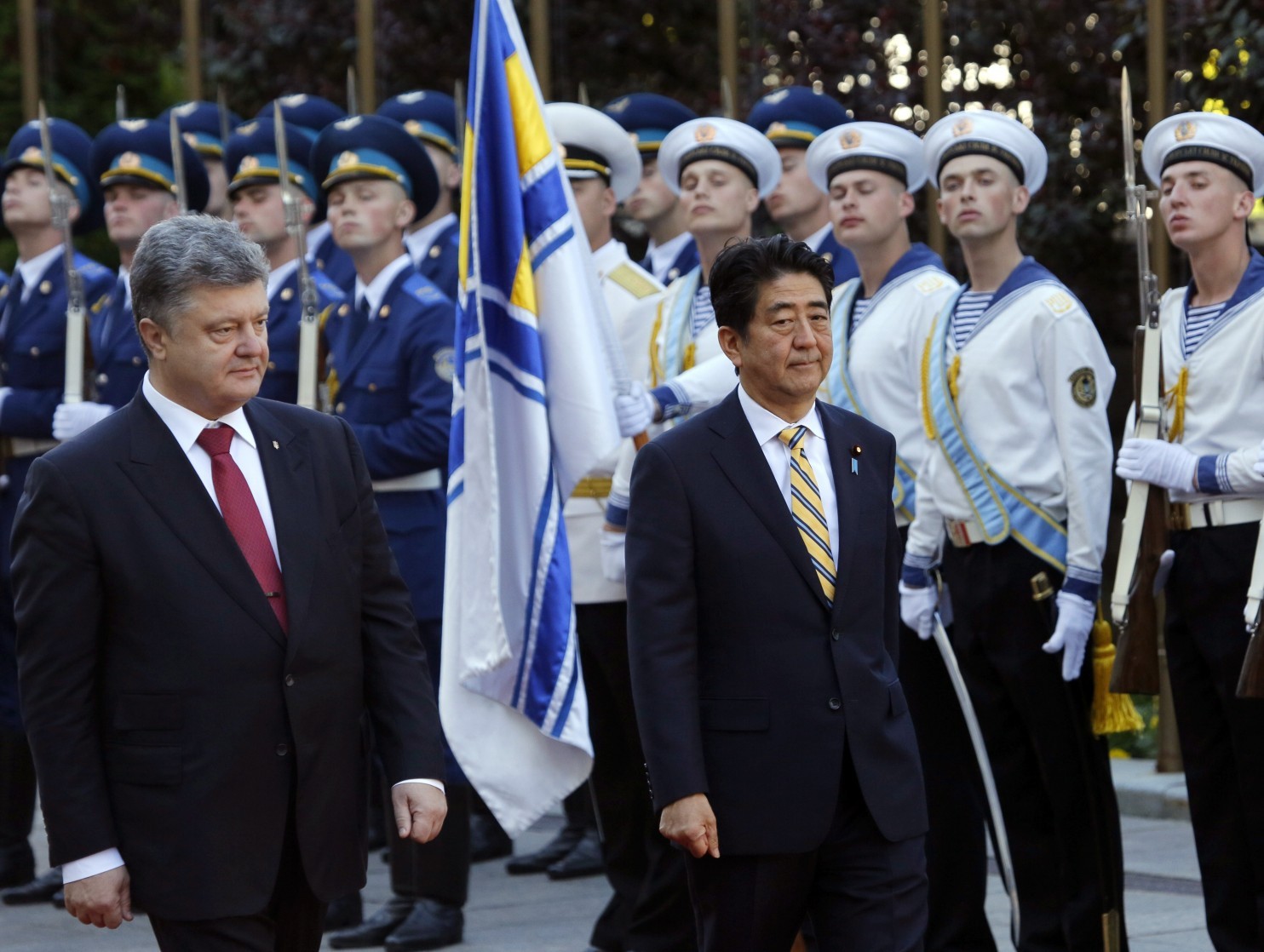

While it has become commonplace for the media to demonize Russia and show support for Ukraine, we should not forget that the real recriminations are being levied behind closed doors. Stephen Harper’s hysterical comments and his visit to Kiev on the eve of the G7 Summit testify to the weakening influence of the Canadian Prime Minister in his own country, and look like feeble attempts to garner votes from the significant Ukrainian diaspora in Canada. Shinzo Abe’s arrival in Kiev also points to the difficulties the Japanese leader is experiencing, although this is mostly with his Western colleagues, who are not happy with his attempts to maintain cordial relations with Russia. But, once again, we should not exaggerate the significance of the Russian factor.

The reality is that the meeting between the G7 leaders and EU representatives is effectively the only opportunity they will have to coordinate and protect their positions in the face of unfavourable economic and political tendencies – and do it without politically correct ambiguity, having discussed each other’s demands and concerns. One major concern is the depreciation of the euro against the dollar. As for cooperation within the G20 framework, it was during this meeting that attempts were made to assess progress in the issues of market regulation and tax systems and propose future initiatives. It is telling that, despite the often conflicting positions of their own citizens and the concern of the most prominent developing countries, the leaders once again identified trans-regional trade initiatives as priorities, specifically the Trans-Pacific Partnership, welcoming the WTO Doha Round.

While only slightly more than half a page of the G7’s 19-page final declaration was given to the conflict in Ukraine, the Group did outline in the foreign policy section its interests and positions on the key challenges facing the world today – ISIS, Syria, Libya, Afghanistan, etc. Special attention was given to the issues of climate change, healthcare and women’s economic empowerment. The Agenda for Sustainable Development, which the UN member states are set to adopt in September 2015, was also covered in the document, without any special additions. The reaffirmation of the G7’s commitment the 0.7 per cent ODA/GNI looks somewhat bleak.

Onward to a Brighter Future?

It would seem that the G7 Summit was an important event for those who took part in it. It was also important in terms of identifying in a very candid manner the opportunities and limitations in the foreign policy activities of individual countries; identifying key threats and possible responses to the challenges facing the G7; and demonstrating the strength and confidence in the course the Group has chosen for its people. Today, the G7 performs an entirely different function from the one it has been carrying out over the past 15 years. It now forms a united front against those who want to reform the world order – those who challenge the West and its “unconditional” right to the ultimate truth. The G7 represents a chance to preserve the status quo and the “bright future”… but only for the chosen ones.