Canada’s Arctic strategy

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 2, rating: 5) |

(2 votes) |

Doctor of Political Science, professor at Saint Petersburg state university, RIAC expert

PhD in Political Science, Professor at the Faculty of International Relations, Saint Petersburg State University, RIAC expert

The issue of potential partners and allies both in the world and in the strategically important Arctic region stands crucial in Russia’s contemporary foreign policy. Is there any chance of finding such partners considering the increased attention to the Arctic and competition in this region? Despite differences between Moscow and Ottawa, Canada is likely to be more ready than all other “official” Arctic powers to collaborate with Russia.

The issue of potential partners and allies both in the world and in the strategically important Arctic region stands crucial in Russia’s contemporary foreign policy. Is there any chance of finding such partners considering the increased attention to the Arctic and competition in this region? Despite differences between Moscow and Ottawa, Canada is likely to be more ready than all other “official” Arctic powers to collaborate with Russia.

Canada’s interests in the Arctic

The Canadian sector of the Arctic comes second by size (25%) after the Russian sector (40%). Canada is one of the five so-called “official” Arctic states (which, apart from Canada, include the U.S., Russia, Denmark and Norway). Under contemporary international law, these countries have pre-emptive legal basis for the economic development of the adjacent Arctic shelf.

Canada’s main interest is on the prospects of oil and gas development. Along with the conventional oil and gas deposits, the coastal area of Canadian Arctic has huge reserves of methane hydrate. If its commercial production is launched, these reserves would last for several hundred years. Nevertheless, about a third of Canada’s proven oil and gas reserves is not in use yet. Technologies safe enough have not yet been developed, and Canada does not conduct drilling on its Arctic shelf. The mechanism for insurance coverage in the event of a major accident or a threat to the environment has not been worked out either. In addition to oil and gas resources, the Canadian North has significant reserves of valuable minerals such as diamonds, copper, zinc, mercury, gold, rare earth metals and uranium.

Most of Ottawa’s political priorities in the Arctic region are on ensuring sustainable socio-economic and environmental development of the Canadian North.

Melting of polar ice increases the navigation time through the so-called Northwest Passage over which Canada is claiming control. In the case of clearing of ice, this strait will be comparable to the economic attractiveness of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) around Russia’s Arctic coast. The fact is that it significantly shortens the route from East Asia to Europe and East Coast of the United States and Canada (as compared with the route through the Panama Canal). Moreover, transit fees are not required to pass through it.

Like Russia, Canada adheres to the sectoral concept of division of Arctic spaces, which is aimed at controlling the Arctic spaces up to the North Pole (i.e. a dividing line is conventionally drawn from the North Pole along the meridian to the extreme east and west points of the continental Arctic coast of Canada).

Canada’s Arctic development strategy

In Canada, the concept “North” is broader than the concept “Arctic”. Geographically, it includes areas both north and south of the Polar Circle: Yukon, Nunavut and Northwest Territories, and the islands and waters to the North Pole, inclusively. The Canadian North accounts for 40% of the land area of the country, but only 107 thousand people live there. As already noted, the maritime borders extending from the Arctic coast of Canada towards the North Pole are determined by Ottawa in accordance with the sectoral concept. The Canadian North has been developed to a much lesser degree than Russia’s Arctic zone both socio-economically and militarily. Therefore, the basic meaning of Ottawa’s Arctic policy is on integrated development of this region.

The main areas of the strategy set out in the white paper entitled “Canada’s Northern Strategy: Our North, Our Heritage, Our Future” (2009) involve the following.

- Protection of Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic sector. The increase of military presence is planned in order to increase control over the land areas, sea and air space in the Arctic.

- Promoting social and economic development of the Canadian North. This is about providing annual grants of $2.5 billion to northern territories for the development of health, education and social services. Development of gas fields near the mouth of the Mackenzie River and diamond mining will be the main sources of wealth in the short term.

- Environmental protection and climate change adaptation. Economic planning will take into account conservation of ecosystems, creation of national parks, transition to energy sources that are not accompanied by emission of carbon into the atmosphere, participation in creating international standards governing economic activities in the Arctic.

- Development of self-government, economic and political activities of northern territories as part of the North development policy. In addition to federal grants, income from mining operations is allocated for these purposes by transferring ownership of part of profitable facilities (gas pipelines, etc.) to indigenous communities.

Obviously, most of Ottawa’s political priorities in the Arctic region are on ensuring sustainable socio-economic and environmental development of the Canadian North. Canada’s arctic strategy is more internal than external in nature (this brings it closer to Russia’s policy in the Far North).

The military and political aspect is important but not decisive in the Northern strategy of Ottawa. Canada has no direct military threats in the Arctic region. The main motive of fortification and even some increase in Canada’s military presence in the region is that today the country does not have either the resources for effective control over the vast expanses of the Far North, or experience in military operations in the Arctic. Historically, Canada has never shown visible military activity in the Arctic. During the Cold War, the country relied on the United States in many ways and therefore, today, it does not have equipped deep-water ports, advanced communications systems, icebreakers and large armed groups in this region. The military tasks set out in Canada’s Northern Strategy are very limited in scope and aimed mainly at eliminating obvious “gaps” in the system of national security in the Arctic and protecting the country’s economic interests in the region. In this context, Ottawa’s actions are similar to measures taken by other Arctic powers.

Russia and Canada in the Arctic: potential for conflict

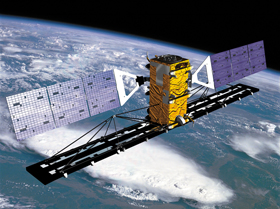

Radarsat-2 is an Earth observation satellite that

was successfully launched December 14, 2007

for the Canadian Space Agency.

Let us dwell more on the problem areas of Russian-Canadian relations in the Arctic.

Territorial disputes. Along with Russia and Denmark, Canada is claiming to extend its shelf to the underwater Lomonosov Ridge by filing a request to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. It was to prove that this ridge is an extension of the North American continental platform that the country, in 2008-2009, conducted a US-Canadian joint shelf survey north of Alaska onto the Alpha-Mendeleev Ridge and eastward toward the Canadian Arctic archipelago. Russia is preparing a similar request (and already filed it in 2001, however, without success). So, Russia and Canada are opponents in this respect.

Claim to the Lomonosov Ridge is not the only territorial dispute Ottawa has with its Arctic neighbors. Canada is also challenging Denmark on the ownership of a small (measuring only 1.3 km2) uninhabited Hans island (this conflict is already close to settlement), and on the borderline in the Lincoln Sea. Canada is also in a dispute with the United States on the maritime border in the Beaufort Sea, where there are presumably oil and gas reserves, as well as on the status of the Northwest Passage (Canada insists on its sovereign rights to this passage, while the U.S. considers it as its international waters). However, these arguments are not considered serious enough to prevent cooperation with these countries, including in the military-political sphere.

Canada’s increased military activity in the Arctic. In an effort to eliminate its lagging behind in the field of military security in the Arctic, Ottawa has in recent years set its sights on expanding its military presence in the region. For example, it plans to build a military training center on the bank of the Northwest Passage in the town of Resolute Bay (595 km from the North Pole) and maritime infrastructure facilities. To strengthen the capacity of the Coast Guard, the country plans to build deep-water berths (in the city of Nanisivik), a new icebreaker named “Diefenbaker”, and three patrol vessels capable of operating in ice conditions. The latest Canadian space satellite RADARSAT-II, the joint Canadian-American system NORAD, intelligence signals interceptor station in the town of Ehlert (Ellesmere Island, Canadian Arctic Archipelago) will all be used to monitor Arctic spaces. Programs have been scheduled to modernize and increase the units of Canadian rangers to 5,000 people by the end of 2012. They will be largely recruited from the local indigenous populations and are expected to monitor and carry out search and rescue operations in the Arctic.

Majority of Canadians believe that reaffirming the country’s sovereign rights on the Arctic is the number one priority in the country’s foreign policy.

In 2010, the Canadian government announced it was buying 65 new F-35 Lightning II fighters from the U.S. for a total of $16 billion, including aircraft maintenance for twenty years. Although it is not quite clear for what purpose Canadians are going to use these fighters in the Arctic. The fact is that F-35 is designed to perform tactical missions in support of ground operations, bombing and conducting close air combat. However, none of the Arctic players has plans to land troops in the Canadian north, and a couple of old Russian bombers conducting mostly training flights to Canada’s air border does not constitute any serious threat. According to experts from the Canadian Defence and Foreign Affairs Institute, these purchases are more likely a security guarantee for the future than a response to today’s challenges. According to other estimates, Canada has other crucial tasks: patrol aircrafts for coast monitoring and a robust naval capacity. These and other initiatives have led to a doubling of Canada’s total military spending compared to the late 1990s [1].

From 2008, Canada began to conduct regular exercises of its armed forces in the Arctic, as well as exercises with the participation of other countries. The stated purpose is to protect Canadian sovereignty in the Far North. Canada has no plans to invite Russia to such exercises. Canada, the U.S. and Denmark are not only conducting joint exercises in the Arctic, but are also performing patrol functions and working out rescue operations on the waters.

Nevertheless, experts urge not to overestimate the importance of these Canadian military preparations, as, in their opinion, it is rather a demonstration of readiness to protect its economic interests and respond to the “non-conventional” (non-military) challenges in the region and not a preparation for a large-scale military conflict. Canadians have neither desire for a large-scale military conflict nor the logistical capabilities. Ottawa still intends to rely on the United States in the area of strategic defense. This scenario seems to it the most beneficial financially and functionally.

The influence of political state of affairs on Ottawa’s Arctic policy. Unfortunately, Canada’s Northern Strategy is often a hostage to election battles. Politicians belonging to different camps take into account the fact that the majority of Canadians believe that reaffirming the country’s sovereign rights on the Arctic is the number one priority in the country’s foreign policy. According to opinion polls, 40% of Canadians are supporters of taking a “hard line” on this issue. Canadian conservatives most often play the Arctic “card” during parliamentary election campaigns. For example, their leader, the current Prime Minister of Canada, Stephen Harper, frequently makes anti-Russian and pro-American statements. Despite the fact that not all Canadians approve Stephen Harper’s anti-Russian rhetoric, such actions by the Canadian leadership do not contribute to closer relations between Moscow and Ottawa on Arctic issues.

Horizons of Russian-Canadian cooperation in the Arctic

Despite the fact that Russia and Canada are competing in the issue of division of the Arctic spaces, they adhere to some general principles, which make their cooperation possible even in this problem area.

The legal basis for Russian-Canadian relations includes the Political Agreement on Consent and Cooperation of June 19, 1992, and a series of economic agreements: Promotion and Reciprocal Protection of Investments (1991); Trade and Commercial Relations (1992); Economic Cooperation (1993); Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with Respect to Taxes on Income and on Capital (1995); Air Communication; Principles and Bases of Cooperation Between the Federal Districts of the Russian Federation and the provinces and territories of Canada (2000); Cooperation in the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy (1989).

There are a number of documents directly dedicated to Arctic issues. For example, the Joint Russian-Canadian Statement on Cooperation in the Arctic and the North was signed on December 18, 2000, which outlined the main directions of bilateral cooperation in the region. In November 2007, during a visit to Canada, the Russian Prime Minister signed a number of sectoral agreements: on Russian-Canadian cooperation in the Arctic, on the use of atomic energy for peaceful purposes, in the field of agriculture, fisheries, veterinary and phytosanitary control, and in the financial field.

Apart from the legal framework, the institutional framework of Russian-Canadian relations is also strengthening. In 1995, a Russia-Canada Intergovernmental Economic Commission (IEC) was created. The IEC structure consists of an industrial agriculture subcommittee and working groups on construction, fuel and energy, mining, the Arctic and the North. As of today, eight IEC meetings have been held. The last session was held in Ottawa in 2011 jointly with the Russian-Canadian forum on animal husbandry and a session of the Canada-Russia Business Council (CRBC) in the format of Russia-Canada Business Summit. The regular ninth meeting of the IEC is expected to be held in Moscow in 2013.

Besides, the Russian-Canadian working group on cooperation in the field of climate change has been operating since September 2002 (formally outside the IEC). The Canada-Russia Business Council (CRBC) was created in October 2005. It includes working groups on agriculture, mining, energy, information and telecommunications technology, transport, finance, and forest industry.

Despite the presence of a potential for conflict, Russia and Canada have many opportunities to establish Arctic cooperation in the following areas.

Trade and economic cooperation. The Northern Air Bridge project involves the creation of an integrated communications system in the Arctic (for example, by launching satellites into highly elliptical orbits and developing the necessary ground infrastructure) to ensure air communication between the airports in Krasnoyarsk and Winnipeg. Another project – Arctic Bridge – involves cross-polar shipping between the port of Murmansk and the port of Churchill.

The largest joint investment projects in the Russian Arctic are:

- purchase and development of the Kupol and Dvoynoe gold fields in Chukotka (Kinross Gold company);

- development of the Mangazeyskoe silver-polymetallic field in Yakutia (Prognoz CJSC/Silver Bear Resources);

- execution of design work and supply of equipment for the third phase of the construction of the Koryaga Oil Fields project in the Nenets Autonomous Okrug (Globalstroy Engineering/SNC LAVALIN);

- development of the Fedorova Tundra field (Murmansk Region);

- mastering the Canadian “cold asphalt” technology in the construction of roads under the extreme climatic conditions of the Arctic (Yakutia);

- design and production of Arctic navigable all-terrain vehicles on air-inflated caterpillars;

- promotion of the deployment of wind-diesel systems that are adapted to operate in the Arctic conditions in the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, etc.

Scientific and technological cooperation. According to the Joint Russian-Canadian Statement on Cooperation in Science, Technology and Innovation signed on June 2, 2011, the parties consider joint activities in the areas of energy and energy efficiency, nanotechnology, biomedical technology, climate research and the Arctic as a priority. In the absence of ice-breakers, special vessels for research in ice conditions, and reliable space communications systems, Canada is interested in attracting the relevant potential of Russia to conduct joint research in the region. The numerous scientific and educational projects of Russia and Canada also include cooperation between Canadian universities and the Northern (Arctic) Federal University (Arkhangelsk).

Ecology. The IEC Arctic and North Working Group is implementing a range of projects under the program entitled “Conservation and Restoration of the Biological Diversity of Northern Territories and the Environmental Protection, Cooperation in the Field of Agriculture and Forestry”.

In 2011, the Russian government decided to allocate in 2011 to 2013 €10 million for the Project Support Instrument being created under the auspices of the Arctic Council. Thus, a collective fund, which will be used to eliminate sources of environmental pollution and the so-called environmental “hot spots” in the Arctic was “launched”. A legally binding document on prevention of oil spills in the Arctic region and combating their consequences is being drafted under the Arctic Council. Among the Council’s major new projects for the next period is creation of mechanisms for ecosystem management of the Arctic environment, integrated assessment of multilateral factors of changes occurring in the region, and trends in human development in a changing Arctic.

Indigenous peoples. In accordance with the Russian-Canadian Declaration of Cooperation in the Arctic (2000), several programs aimed at creating favorable conditions for the life of the indigenous peoples of the North are being implemented. One of such programs – Exchange of Experience in Managing Northern Territories – launched in 2011, is being implemented with the participation of the Plenipotentiary Representative of the Russian President in the Siberian Federal District and the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. The Institute of Economics and Industrial Engineering, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences is providing the needed scientific support.

From 2006 to 2009, a Russian-Canadian cooperation program for the development of the North was implemented with the participation of the Canadian International Development Agency, the Ministry of Regional Development of the Russian Federation, and a number of Russian agencies on issues concerning the indigenous minorities in the North. The program was conducted in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug, and the Khabarovsk Krai. Development of natural resources use and small business is among its projects aimed mainly at humanitarian cooperation.

Under the IEC Arctic and North Working Group, Russia and Canada are implementing numerous projects on creating a model territory of traditional nature management for the indigenous minorities, on development of local kinds of sports, and on cultural exchanges between the indigenous peoples of the Russian and Canadian North.

Under the Arctic Council, Russia is working to establish a public Internet archive of data about the development and culture of the Arctic (“Electronic Arctic Memory”), supporting young reindeer breeders of the North, working with organizations of indigenous peoples to clear the area of sources of environmental pollution, etc.

Resolving territorial disputes. Despite the fact that Russia and Canada are competing in the issue of division of the Arctic spaces, they adhere to some general principles, which make their cooperation possible even in this problem area. First, the two countries are in support of resolving disputes through negotiations and based on international law. That is how Moscow and Ottawa are planning to solve the dispute regarding the underwater Lomonosov Ridge, potentially rich in oil and gas resources. Secondly, both countries favor the sectoral principle of dividing the Arctic spaces (when the North Pole is seen as a point from where direct lines are drawn along the longitude). This principle is more favorable to them than the so-called “median line method”, where the division is based on the principle of equidistance of the boundary line from the coastline (or reference points of the coastline) of adjoining states. Applying the sectoral principle would significantly increase the area of the Arctic controlled spaces of Russia and Canada. Thirdly, Russia and Canada are in favor of consolidating the status of transit sea routes in the Arctic (Northern Sea Route and Northwest Passage) as internal waters, which would fetch the two countries considerable economic benefits.

Cooperation within international organizations. Both countries assign a special role in this regard to the Arctic Council created at Canada’s initiative in 1996. The main common goal of the two countries is to transform the Arctic Council into a leading (and full-fledged) international organization with the right to make decisions binding on its members. According to Moscow and Ottawa, it is the Arctic Council, which should be the body where all the major problems of the Arctic region – from environmental and transport security issues to protection of the rights of the indigenous minorities of the Arctic, and cultural cooperation – should be solved. As already noted, not all the Arctic Council members agree to such a plan. The United States verbally recognizes the importance of this international institution, but de facto, for the entire duration of its existence has been sabotaging its activities.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and

Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada,

Lawrence Cannon

Russia and Canada have long proposed to more precisely define the status of permanent observers to the Arctic Council for non-Arctic states and international organizations. This would allow clearly defining the limits of non-Arctic states and international organizations in the Arctic, confirming at the same time the priority of the five Arctic states (this is beneficial both for Russia and for Canada, which have the longest borders in the Arctic). In the end, such a document allowing streamlining the process of granting a permanent observer status to non-Arctic states and organizations, and clearly defining the rights and obligations of the Arctic Council permanent observers, was drawn up and signed at the Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting in Nuuk, Greenland, in May 2011. The next Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting which is planned for 2013 will decide on who else to grant a permanent observer status in the Council.

To enhance the influence of the Arctic Council, Moscow and Ottawa have long proposed that a standing secretariat should be established and funded for a more efficient operation of the working groups of the Council. It was under the Russian and Canadian influence at the ministerial meeting in Nuuk that it was decided to create a full-fledged Arctic Council secretariat, located in Tromso (Norway). The secretariat’s budget will be relatively small. Most of the budget will be money to pay for the work of 10 employees, including the head of the secretariat. The budget also provides for their maintenance and payment of business travels to various events. The approximate amount is €1 million. For program projects, contributions will be used in addition to the regular budget.

It is important to note that the growing influence of the Council in the region prevents NATO’s claims to become the main security “provider” in the Arctic (the U.S. is especially eager for this).

Security. Moscow and Ottawa have taken certain steps to cooperate in this area. Since 1994, there has been an interdepartmental memorandum on cooperation in the military area, according to which the parties exchange visits by high-ranking military officials and conduct military staff talks. Since 2002, Canada has been participating in the Global Partnership program under which, in 2004, the two countries signed a bilateral intergovernmental agreement on cooperation in the destruction of chemical weapons, dismantlement of nuclear submarines decommissioned from the Navy, accounting, control and physical protection of nuclear materials and radioactive substances. Canada announced it was allocating one billion Canadian dollars over ten years (100 million Canadian dollars annually) for this purpose. Most of these projects are being implemented in the Russian Sub-Arctic.

In line with Ottawa’s policy to demilitarize the Arctic, it is necessary to consider its initiative to create in the region a zone free of nuclear weapons. As a whole, Russia sees this initiative positively (let’s recall that Moscow acted with a similar idea at the time of Mikhail Gorbachev), but it has a question about the geographical scope of such a zone. Russia agrees to the establishment of a nuclear-free zone in the Arctic, provided that this would not affect stationing of troops and the activities of the Russian Northern Fleet consisting of 2/3 strategic submarines equipped with nuclear weapons.

In recent years, the Russian-Canadian cooperation in the field of the so-called “soft security” (new threats and challenges posed by climate change and expansion of economic activity in the Arctic) has been growing. Issues such as navigation safety, the danger of pollution of the marine environment, expansion of the scale of illegal migration, transnational organized crime and terrorist activities are increasingly taking the central stage.

It seems that a concerted policy of the Canadian government departments and civil society institutions of Russia will allow, on one hand, neutralizing the potential for conflict in Russian-Canadian relations, and on the other, strengthening the bilateral, multilateral, and non-aligned cooperation in the Arctic.

1. Blunden M. The New Problem of Arctic Stability // Survival. 2009. Vol. 51. No, 5. P. 127.

(votes: 2, rating: 5) |

(2 votes) |